Leonardo da Vinci had the world’s most observant and creative mind. With an estimated IQ well over 190 — probably 200+ — da Vinci was a true, versatile Renaissance man. He was far ahead of his time in art, anatomy, architecture, engineering, mathematics and many other disciplines. Few came even close to Leonardo’s prolific output of artistic masterpieces and scientific discoveries. And many deeply pondered the astounding secret behind Leonardo da Vinci’s creative genius.

Leonardo da Vinci had the world’s most observant and creative mind. With an estimated IQ well over 190 — probably 200+ — da Vinci was a true, versatile Renaissance man. He was far ahead of his time in art, anatomy, architecture, engineering, mathematics and many other disciplines. Few came even close to Leonardo’s prolific output of artistic masterpieces and scientific discoveries. And many deeply pondered the astounding secret behind Leonardo da Vinci’s creative genius.

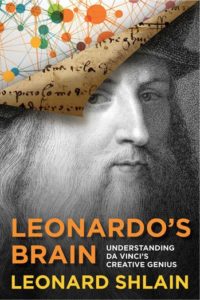

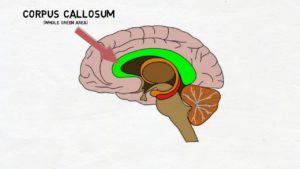

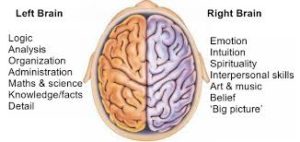

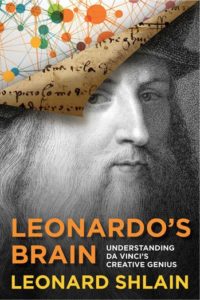

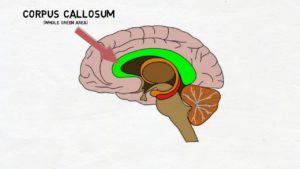

Author Leonard Shlain spent years exploring da Vinci’s work and analyzing what made him so outstanding. In the book Leonardo’s Brain: Understanding da Vinci’s Creative Genius, Shlain makes an excellent case that Leonardo da Vinci was biologically different from practically all other humans. According to Shlain, da Vinci’s brain was the perfect balance of right and left hemispheres. It was because of a one-of-a-kind abnormality in Leonardo da Vinci’s corpus callosum—the part of the brain responsible for controlling analytical left-brain observation and right-brain creativity.

In Understanding da Vinci’s Creative Genius, Leonard Shlain did what he calls a “postmortem brain scan”, seeking to illuminate the exquisite wiring inside Leonardo da Vinci’s head. It’s an in-depth psychological/neurological profile about what’s known of da Vinci’s phenomenal behavior and the ingenuity of his works. At the end of this fascinating book, Shlain concludes that Leonardo da Vinci’s brain was so advanced that his understanding of all things in nature and his grip on personal creative ability allowed him to access unique ways of thought.

In Understanding da Vinci’s Creative Genius, Leonard Shlain did what he calls a “postmortem brain scan”, seeking to illuminate the exquisite wiring inside Leonardo da Vinci’s head. It’s an in-depth psychological/neurological profile about what’s known of da Vinci’s phenomenal behavior and the ingenuity of his works. At the end of this fascinating book, Shlain concludes that Leonardo da Vinci’s brain was so advanced that his understanding of all things in nature and his grip on personal creative ability allowed him to access unique ways of thought.

Shlain postulates that da Vinci saw universal interconnectedness in everything… everywhere. Biologically advantaged by some quirk of nature, da Vinci elevated his mind to a higher state of consciousness than achieved by other people. Leonardo da Vinci—according to author Leonard Shlain—evolved into a superhuman.

* * *

Genetically, there didn’t appear to be anything special about Leonardo da Vinci. He was born out of wedlock in 1452 at the Italian town of Vinci in the Florence region. His mother was a peasant and his father was a notary—somewhat of a playboy. Infant and toddler Leonardo was raised by his mother and neglected his father who only supplied modest child support.

Because Leonardo da Vinci came from low class, he wasn’t eligible for a formal education as were nobility associated with the church and state. In fact, da Vinci had no conventional schooling as a youth. He wasn’t able to learn the “secret code” associated with the education of the time. That was learning to speak, read and write Latin and Greek which unlocked the doors to classical learning. Without knowing these two prominent languages, it was practically impossible for da Vinci to conventionally participate in making the Renaissance.

Because Leonardo da Vinci came from low class, he wasn’t eligible for a formal education as were nobility associated with the church and state. In fact, da Vinci had no conventional schooling as a youth. He wasn’t able to learn the “secret code” associated with the education of the time. That was learning to speak, read and write Latin and Greek which unlocked the doors to classical learning. Without knowing these two prominent languages, it was practically impossible for da Vinci to conventionally participate in making the Renaissance.

Leonardo da Vinci was taken from his dysfunctional mother at age 5 or 6. His kindly uncle Francesco did the best he could to provide for the boy. Regardless of his lack of formal schooling, da Vinci showed a remarkable curiosity and intellectual ability right from a young age. He seemed “gifted” and was able to visualize abstracts including art forms and mathematical equations far beyond normality. Soon, the Florentine painter and artistic leader Andrea del Verrocchio saw a protégé and took Leonardo da Vinci under his wing.

For most of his life, the European world recognized Leonardo da Vinci as a painter. In reality, da Vinci wasn’t a prolific painter. He painted sporadically and nominally as a side-line commission. Art experts at Christie’s auction in New York estimate that over 80 percent of Leonardo da Vinci’s paintings were lost over the years. Today, there are only 15 verified da Vinci paintings in the world including Mona Lisa, The Last Supper and Annunciation. Salvator Mundi sold in 2017 for $450.3 million US.

For most of his life, the European world recognized Leonardo da Vinci as a painter. In reality, da Vinci wasn’t a prolific painter. He painted sporadically and nominally as a side-line commission. Art experts at Christie’s auction in New York estimate that over 80 percent of Leonardo da Vinci’s paintings were lost over the years. Today, there are only 15 verified da Vinci paintings in the world including Mona Lisa, The Last Supper and Annunciation. Salvator Mundi sold in 2017 for $450.3 million US.

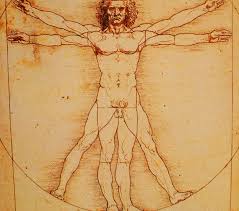

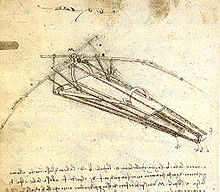

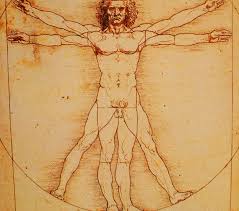

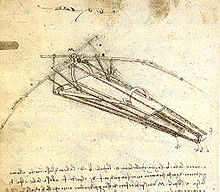

But Leonardo da Vinci was really prolific in his drawings and writing. His anatomical sketches, scientific diagrams and thoughts across the spectrum fill volumes now held in private collections and public museums. Da Vinci’s unquenchable curiosity and feverishly inventive imagination consumed his waking hours. The world is extremely fortunate that many of Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks still exist.

Da Vinci’s interest held no bounds. He was a true polymath who studied astronomy, anatomy, architecture, botany, engineering, science, music, math, language, literature, geology, paleontology, ichnology, painting, drawing and sculpting. Leonardo da Vinci also invented. Concepts for the helicopter, parachute and airplane wing came from da Vinci. He even built the first automated bobbin winder before the sewing machine came to be, and Leonardo worked with solar power, double-hulled ships and even armored military tanks. He also thought-out a robotic knight.

Unlike most innovators who are a fine-line between nut and genius, Leonardo da Vinci was incredibly well-balanced on an emotional scale. Besides having an extremely high intelligence quotient (IQ), it’s said Leonardo had a tremendous emotional quotient (EQ) as well. Nowhere is there any suggestion he was an egomaniac or unapproachable. History indicates da Vinci was a pacifist, vegan and humanitarian with a good sense of humor.

So what made Leonardo da Vinci so special? Short answer—his brain. There was something nearly out-of-this-world going on in da Vinci’s mind. And there might be a scientific explanation what it was.

Twenty-first-century science knows a bit of how the human brain functions. But, it’s far from comprehensive knowledge. Science has almost no grasp or understanding of how human consciousness works, and there’s a good reason for that. Brain science is tangible where grey matter can be physically dissected and electrophysiological waves are recordable on computerized graphs. You can fund, study and measure with reports.

Consciousness is a whole different matter. Conventional science has no grip on what human consciousness—or any form of consciousness—really is because it’s non-tangible and can’t be defined within current terms. Because consciousness is slippery, it’s not fundable. There’s no money in it. You can’t measure to monetize it. So consciousness study is left to individual groundbreaking leaders like David Chalmers and Sir Roger Primrose… but back to da Vinci.

Consciousness is a whole different matter. Conventional science has no grip on what human consciousness—or any form of consciousness—really is because it’s non-tangible and can’t be defined within current terms. Because consciousness is slippery, it’s not fundable. There’s no money in it. You can’t measure to monetize it. So consciousness study is left to individual groundbreaking leaders like David Chalmers and Sir Roger Primrose… but back to da Vinci.

Leonardo’s Brain: Understanding da Vinci’s Creative Genius takes a really good look at how LDV’s brain activated his mind to tap into a higher state of consciousness—the world of “Forms”, as Plato termed it, or the source of where all “in-form-ation” sits. In current consciousness research, there’s a distinct difference between the physical brain, the non-physical mind and the plane of infinite intelligence where all ideas come from.

Leonardo da Vinci’s brain was so evolved—author Shlain writes—that his mind easily accessed information not readily there for normal people. Da Vinci’s brain/mind power was so special that he “thought” his way to fantastic ideas. It also let da Vinci observe what was going on in the universe and record it. That might have been simplistic beauty as in the Lady With an Ermine, an anatomical analogy like Vitruvian Man or a geometric complexity seen in the Rhombicuboctahedron.

Leonardo da Vinci’s brain was so evolved—author Shlain writes—that his mind easily accessed information not readily there for normal people. Da Vinci’s brain/mind power was so special that he “thought” his way to fantastic ideas. It also let da Vinci observe what was going on in the universe and record it. That might have been simplistic beauty as in the Lady With an Ermine, an anatomical analogy like Vitruvian Man or a geometric complexity seen in the Rhombicuboctahedron.

Despite Leonardo da Vinci being bright, talented and affable, he was an outlier in the Renaissance period. Da Vinci was biologically different. He was a misfit in the world of conventional ideas and creativity. He thought different. He acted different. He dressed and talked different. That made others uncomfortable. Back then, da Vinci sat at the back of the bus and today he’d still be so far ahead that the rest of us would see dust. Author Leonard Shlain tells us his version why:

“Leonardo da Vinci’s left and right brain hemispheres were intimately connected in an extraordinary way. Because of a large and uniquely developed corpus callosum, da Vinci’s left and right sides constantly communicated and kept each other in the loop on observations and creative options. Each brain side knew what the other was doing, and this gave da Vinci’s mind unprecedented and unrestricted freedom to observe, understand and create.

“Leonardo da Vinci’s left and right brain hemispheres were intimately connected in an extraordinary way. Because of a large and uniquely developed corpus callosum, da Vinci’s left and right sides constantly communicated and kept each other in the loop on observations and creative options. Each brain side knew what the other was doing, and this gave da Vinci’s mind unprecedented and unrestricted freedom to observe, understand and create.

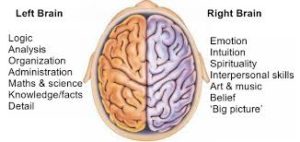

In current brain science, the left hemisphere is the analytical and conservative side. The right is the creative, liberal sphere. Brain scientists think that’s nature’s safety mechanism to prevent humans from getting too stupid or smart in either extreme. Da Vinci’s brain seems to have found the middle ground—the apex of the triangle or the tip of the see-saw.”

In Leonardo’s Brain: Understanding da Vinci’s Creative Genius, Leonard Shlain backs-up his theory with facts. The most interesting fact supporting da Vinci’s left/right corpus callosum uniqueness is his handiness. Leonardo da Vinci was a southpaw—he was left-handed.

In Leonardo’s Brain: Understanding da Vinci’s Creative Genius, Leonard Shlain backs-up his theory with facts. The most interesting fact supporting da Vinci’s left/right corpus callosum uniqueness is his handiness. Leonardo da Vinci was a southpaw—he was left-handed.

Left-handers aren’t that unusual in human population. Studies show approximately 8-10 percent prefer left-hand prominence. A tiny proportion are ambidextrous, but the vast majority have manual-dexterous abilities with their right. However, there are unusual advantages south-paws have. They tend to be far more creative than right-handers.

It’s no news the left side of the brain controls the right side of the body—same with vise-versa. When one hemisphere is dominant over the other, a person is usually analytical or creative. But, when both sides are equally balanced, something phenomenal happens.

Anatomically, the corpus callosum—aka the callosal commissure—is a wide and thick nerve bundle sitting at the brain’s foundation. It’s the largest white matter brain structure that binds the left and right gray matter. The corpus callosum isn’t big. It’s about 10 centimeters or 4 inches long. Neurologically though, it’s huge—having about 250 million axonal projections.

The corpus callosum regulates electrical activity happening in the left and right brain sides. It’s got a big job to do. One of its jobs is responsible for the primordial fight-flight response ingrained in all of us. But the corpus callosum also lets humans get imaginative, like the right brain inventing tools to slay saber-toothed tigers while the left side stays alert.

The corpus callosum regulates electrical activity happening in the left and right brain sides. It’s got a big job to do. One of its jobs is responsible for the primordial fight-flight response ingrained in all of us. But the corpus callosum also lets humans get imaginative, like the right brain inventing tools to slay saber-toothed tigers while the left side stays alert.

The Leonardo’s Brain: Understanding da Vinci’s Creative Genius book goes beyond a left/right brain dichotomy. It delves deep into something uniquely known about da Vinci’s left-handedness. Leonardo da Vinci’s brain let him write left-handedly in a mirror image. Da Vinci’s writings, notes and diagram annotations have him writing right to left where you need a mirror to decipher them.

This mirror-image phenomenon provides profound insight into Leonardo da Vinci’s psyche. Here is a poor-boy without formal education who developed his own style independent of traditional academic influences—even choosing which hand to use and how to communicate with. Da Vinci was the poster-boy of self-taught, self-investigating and self-assured individuals—the likes the world never experienced in his time or so-far thereafter.

This mirror-image phenomenon provides profound insight into Leonardo da Vinci’s psyche. Here is a poor-boy without formal education who developed his own style independent of traditional academic influences—even choosing which hand to use and how to communicate with. Da Vinci was the poster-boy of self-taught, self-investigating and self-assured individuals—the likes the world never experienced in his time or so-far thereafter.

Leonardo da Vinci’s lack of indoctrination by limiting dogma taught through conventional institutions like the church and its lap-dog societal constraints liberated him from mental restraints. Combined with perfect neuro-equilibrium between inquisitive left and creative right brain functions, da Vinci broke free of earthly bounds and set his mind soaring into airy lofts not there for common minds.

Author Leonard Shlain of Leonardo’s Brain: Understanding da Vinci’s Creative Genius makes another interesting observation and conclusion. Because da Vinci was removed from his biological mother’s hold so early, he became mentally self-reliant. Da Vinci was also gay or at least asexual. He wasn’t driven by a common male preoccupation with the little head thinking for the big one.

Brain science recognizes that “normal” human brain thoughts primarily focus on survival concerns like food, shelter and sex. That didn’t seem a factor with Leonardo as he progressed in life. He just abnormally sensed reality. Then he painted, sketched or wrote what he knew.

No, Leonardo da Vinci was much more than “normal”. He was the prime exemplar of a universal genius whose brain far out-thought humankind. Looking back… and forward, if da Vinci showed up for a job interview, his unique selling proposition on his resume would be “I have an unusual brain and my mind knows how to use it”.

That’s the astounding secret behind Leonardo da Vinci’s creative genius.

Happy 2019 everyone from Garry Rodgers & DyingWords.net. To start things off right, here’s a special New Years promotion. My psychological crime thriller No Life Until Death is a FREE Amazon Kindle e-Book for the New Year season only. By-pass the party hats, noisy horns and morning headache by staying up late reading something that’ll really ring in. Get your FREE digital copy of No Life Until Death by downloading it here. You can also read it on Kindle Unlimited or email me for an ePub or PDF copy at garry.rodgers@shaw.ca.

Happy 2019 everyone from Garry Rodgers & DyingWords.net. To start things off right, here’s a special New Years promotion. My psychological crime thriller No Life Until Death is a FREE Amazon Kindle e-Book for the New Year season only. By-pass the party hats, noisy horns and morning headache by staying up late reading something that’ll really ring in. Get your FREE digital copy of No Life Until Death by downloading it here. You can also read it on Kindle Unlimited or email me for an ePub or PDF copy at garry.rodgers@shaw.ca. No Life Until Death is a sequel to No Witnesses To Nothing. It’s the second in a series featuring Inspector Sharlene Bate and the perils she finds. This is the first time No Life Until Death has been released as a Kindle Freebie so take advantage of this thrilling crime story while you have time. Here’s the jacket blurb to give you an idea what’s inside No Life Until Death and why it’s sure to keep you turning pages long after Auld Lang Syne.

No Life Until Death is a sequel to No Witnesses To Nothing. It’s the second in a series featuring Inspector Sharlene Bate and the perils she finds. This is the first time No Life Until Death has been released as a Kindle Freebie so take advantage of this thrilling crime story while you have time. Here’s the jacket blurb to give you an idea what’s inside No Life Until Death and why it’s sure to keep you turning pages long after Auld Lang Syne. Molly Playfair and Emma Bate have something else in common besides age—an AB Positive blood-type—one of the rarest on earth. Only matching organs will save Molly’s life, forcing the Playfairs to hire unscrupulous scalpels in the Philippines and buy her a transplant through the underground world of human organ trafficking.

Molly Playfair and Emma Bate have something else in common besides age—an AB Positive blood-type—one of the rarest on earth. Only matching organs will save Molly’s life, forcing the Playfairs to hire unscrupulous scalpels in the Philippines and buy her a transplant through the underground world of human organ trafficking.