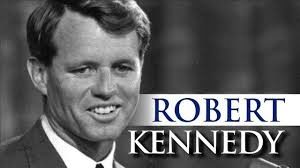

It’s been 50 years since United States Senator Robert Francis (Bobby) Kennedy’s murder in the kitchen of Los Angeles’ Ambassador Hotel. Bobby Kennedy just won the California Democratic nomination as their presidential candidate. Kennedy left the hotel ballroom after his acceptance speech and cut through the pantry where he suffered three bullet wounds, one of them fatal. Caught red-handed—holding a smoking gun—was Christian Palestinian immigrant Sirhan Bishara Sirhan, later convicted of RFK’s assassination.

It’s been 50 years since United States Senator Robert Francis (Bobby) Kennedy’s murder in the kitchen of Los Angeles’ Ambassador Hotel. Bobby Kennedy just won the California Democratic nomination as their presidential candidate. Kennedy left the hotel ballroom after his acceptance speech and cut through the pantry where he suffered three bullet wounds, one of them fatal. Caught red-handed—holding a smoking gun—was Christian Palestinian immigrant Sirhan Bishara Sirhan, later convicted of RFK’s assassination.

Despite overwhelming evidence that Sirhan intentionally shot at Bobby Kennedy, there’re dark doubt shadows looming over the case. They indicate Sirhan didn’t act alone. Problems with witness statements, autopsy findings and ballistic testing suggest evidence that a second gunman conspired in RFK’s shooting. Mistakes and incompetence in the original police investigation also amplify suspicion of a second gunman accomplice.

A highly-credible medical team recently reviewed the original RFK medical and autopsy evidence. For the first time in history, independent professionals looked at the facts and circumstances surrounding Kennedy’s injuries and treatment. In June 2018, they published findings in a medical field’s leading gazette, the Journal of Neuroscience. This clear and concise report examines what happened from a medical perspective and whether there’s any pathological basis providing evidence that a second gunman helped shoot Bobby Kennedy to death.

A highly-credible medical team recently reviewed the original RFK medical and autopsy evidence. For the first time in history, independent professionals looked at the facts and circumstances surrounding Kennedy’s injuries and treatment. In June 2018, they published findings in a medical field’s leading gazette, the Journal of Neuroscience. This clear and concise report examines what happened from a medical perspective and whether there’s any pathological basis providing evidence that a second gunman helped shoot Bobby Kennedy to death.

RFK’s Deadly Road Towards the Presidency

In 1968, Bobby Kennedy seemed certain to win the Democratic Party’s nomination for United States President. Riding on his experience as his brother John F. Kennedy’s attorney general, sympathy over JFK’s assassination and the famous Kennedy name, RFK was well on his road to winning the American presidency. Lyndon Johnson declined a second term, and other Democratic candidates ran a distant second to RFK’s popularity.

Despite being admired, Bobby Kennedy had his enemies. As AG, RFK took on the mob and the communists as well as volatile groups like the Teamsters Union and the Ku Klux Klan. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover hated the Kennedys, and the high profile name made Bobby a target for right-wing activists and lefty nut cases alike. Without a doubt, there were many sights gunning for Robert F. Kennedy.

Despite being admired, Bobby Kennedy had his enemies. As AG, RFK took on the mob and the communists as well as volatile groups like the Teamsters Union and the Ku Klux Klan. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover hated the Kennedys, and the high profile name made Bobby a target for right-wing activists and lefty nut cases alike. Without a doubt, there were many sights gunning for Robert F. Kennedy.

Unlike today’s tight reins, there was little security for presidential primary candidates back in 1968. The Secret Service had no detail for political candidates, and they did little or no threat assessment or background checks on anyone thought dangerous to candidates. RFK’s security team consisted of a retired NFL linebacker, a former Olympic Medalist and a hired part-time security guard carrying a .38 Special. That’s all the protection Bobby Kennedy had when he arrived at the Ambassador Hotel in downtown LA.

Securing the California primary significantly strengthened RFK’s run for the White House. Democratic runner-up, Senator Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota, fell further behind as did former Vice President Hubert Humphrey. Republican presidential candidate Richard Nixon seemed certain to be Kennedy’s challenge for the Oval Office. Had Kennedy lived, Nixon might have lost, and Watergate would never have happened.

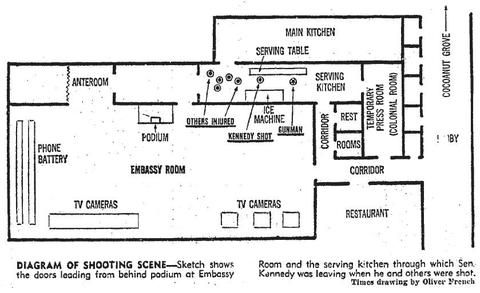

That’s not how history went down. On June 4, 1968 Bobby Kennedy won the California Democratic nomination and gave a rousing acceptance speech to a packed house of enthusiastic supporters. Just after midnight, at 12:15 am on June 5, Kennedy stepped from the podium and exited to the kitchen where a smaller crowd of hotel staff and assistants wished him well. RFK moved through the packed pantry, shaking hands and acknowledging folks.

That’s not how history went down. On June 4, 1968 Bobby Kennedy won the California Democratic nomination and gave a rousing acceptance speech to a packed house of enthusiastic supporters. Just after midnight, at 12:15 am on June 5, Kennedy stepped from the podium and exited to the kitchen where a smaller crowd of hotel staff and assistants wished him well. RFK moved through the packed pantry, shaking hands and acknowledging folks.

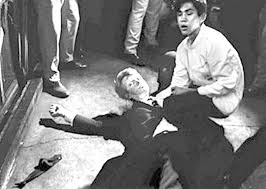

Sirhan laid in wait at the galley’s west end. As Kennedy approached, Sirhan whipped out a .22 caliber, 8-shot Iver Johnson Cadet revolver and emptied it towards RFK. Bullets struck Kennedy three times and collaterally wounded five bystanders. Bobby Kennedy fell to the floor, semi-conscious but mortally wounded with a gunshot wound to the brain. Kitchen staff jumped Sirhan. They wrested the now-empty gun from his hand.

RFK lay motionless for 17 minutes before first responders arrived. A dispatch communication mistakenly sent Kennedy to the nearby Central Receiving Hospital instead of the larger Good Samaritan Hospital which was far better equipped to handle cranial gunshot wounds. Assessing Kennedy’s grave condition, Central’s staff transferred him directly to Samaritan. The delay took nearly an hour post-shooting, however, the 2018 medical review determined it made no difference to RFK’s fate. Despite heroic surgery attempts, his brain wound was untreatable.

Robert Francis Kennedy died at 1:44 am on June 6, 1968. The nation mourned another Kennedy assassination. RFK’s road to the presidency ended in violence, and his dream of furthering civil rights and middle-class prosperity died with him. Sirhan stood trial as the lone gunman. He was convicted, sentenced to death, but later commuted to life in prison. Today, Bobby Kennedy rests under the grounds of Arlington and Sirhan sits behind bars in San Diego.

The RFK Conspiracy Theories Start

Like most high-profile deaths, there are those refusing to buy official conclusions despite how solid evidence seems. John Kennedy’s assassination is the mother of all conspiracy theories, but little brother Bobby’s fate is no exclusion. In fact, there are three deeply disturbing discrepancies in the RFK murder worth investigating.

The big problems with the RFK assassination lie in the true number of shots fired as well as the position and distance of Sirhan relative to Kennedy in the kitchen. Officially, Sirhan fired all 8 shots in his revolver from the front and approximately 2 to 3 feet ahead of RFK. Unofficially, more than 8 shots went off with some bullets allegedly fired from behind Robert Kennedy. That suggests a second gunman.

Further, the eye-witness evidence appears clear that Sirhan maintained some distance, firing from the front on a level and downward angle. The medical and autopsy evidence seems clear that RFK’s fatal brain wound came from a near point-blank gunshot occurring behind his right ear and from an upward angle. Again, that suggests a second gunman.

On the surface, this conflicting evidence is more than troubling. There was also trouble during Sirhan’s trail with inaccurate testimony and confusion by police forensic experts over identifying the RFK murder weapon. There were so many errant issues raised that the United States government appointed a 1975 commission to reinvestigate the RFK assassination. It was supported by the FBI who took no role in the original murder case as the Los Angeles Police Department maintained primary jurisdiction.

The RFK reinvestigation struggled with inconsistent witness statements, confusing forensic evidence and now-missing pieces to the puzzle. Despite perceived problems with proof and procedure, the commission ruled Sirhan Bishara Sirhan acted alone. They found no credible evidence of a second gunman. That was despite being unable to explain a few troubling issues.

The RFK reinvestigation struggled with inconsistent witness statements, confusing forensic evidence and now-missing pieces to the puzzle. Despite perceived problems with proof and procedure, the commission ruled Sirhan Bishara Sirhan acted alone. They found no credible evidence of a second gunman. That was despite being unable to explain a few troubling issues.

Many people don’t accept Sirhan’s original trial verdict or the commission conclusions. This takes in members of the Kennedy family like Robert F. Kennedy, Junior. As well, some of the victims wounded in the Ambassador Hotel shooting and various eyewitnesses present at the time are convinced of a second gunman. Like other conspiracy theorists, they point to the perceptual problems associated with the number of shots and the location of RFK’s fatal wound.

No sensible spectator or serious student of the RFK assassination suggests Sirhan didn’t fire 8 shots. That evidence is overwhelming. But, there’s a lot of information published pointing to more than eight bullet strikes in the Ambassador kitchen. How credible that information is—is the question.

The other major issue—according to conspiracy promoters—is the head wound. By all official accounts, Sirhan never got within a few feet of RFK and remained facing him from the front. The medical and autopsy evidence clearly shows stippling from gunpowder residue burns on Kennedy’s skin and hair at the bullet entrance wound. That evidence seems consistent with the fatal firearm being discharged within inches of RFK’s head, not several feet.

The 2018 independent review published in the Journal of Neurosurgery examined RFK’s hospital treatment and autopsy evidence. They didn’t deal with the “more-than-8-shots” issue. The expert panel left that for the conspiracy theorists and those wanting to research RFK crime scene examination evidence.

The 2018 Journal of Neurosurgery (JNS) Review

Three prominent neurosurgeons and trauma practitioners privately reviewed RFK’s medical records and autopsy report. This was independent of any government agency or special interest group. First, they outlined the history of Robert Kennedy’s campaign and the circumstances bringing him in contact with Sirhan.

Next, the review panel outlined RFK’s emergency treatment and follow-up surgery as well as post-op care. Then, the panel focused on the so-called “perfect autopsy” performed by the famous Los Angeles coroner and forensic pathologist, Dr. Thomas Noguchi. Finally, the experts reassessed Kennedy’s medical care to see if anything more could have been done to save RFK’s life.

Next, the review panel outlined RFK’s emergency treatment and follow-up surgery as well as post-op care. Then, the panel focused on the so-called “perfect autopsy” performed by the famous Los Angeles coroner and forensic pathologist, Dr. Thomas Noguchi. Finally, the experts reassessed Kennedy’s medical care to see if anything more could have been done to save RFK’s life.

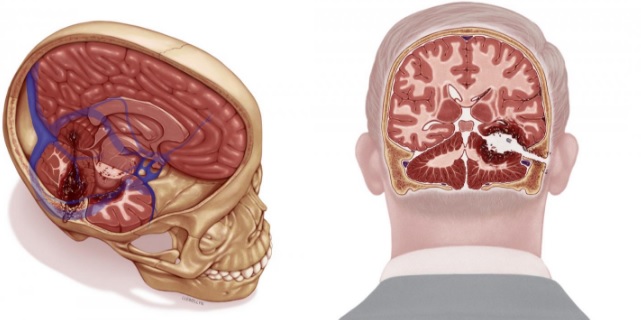

Robert F. Kennedy suffered 3 separate .22 caliber gunshot wounds. Two were superficial and non-life-threatening. The third was ultimately fatal. One entered the right side of his back. This bullet was recovered intact inside RFK’s body. The second non-lethal bullet entered his right armpit and exited his shoulder. It was not recovered. The fatal bullet entered RFK’s skull behind his right ear. It fragmented, sending lead shrapnel and bone chips deep into RFK’s brain, remaining in the gray matter.

The JNS report outlines the brain injury and medical treatment in impressive detail. The doctor panel concludes so much cranial damage occurred that it was a miracle RFK lived as long as he did. They credit the 1968 medical intervention as first-rate. They report even with today’s medical advancements, if RFK was shot this way in 2018, no modern trauma team would be able to save him.

The JNS panel confirmed Dr. Noguchi’s autopsy findings of close-contact gunshot residue (GSR) stippling identified at RFK’s headshot entrance wound. They correctly observed in the autopsy report Noguchi made no reference to the distance the firearm’s muzzle was from RFK’s skin at discharge. Rather, they reported “a discrepancy between eyewitness reports that Sirhan came no closer than 12 to 18 inches from Kennedy when the shooting occurred and Noguchi’s later writings, stating the gun was no more than 3 inches of the right ear when fired”.

The JNS team also referenced a public Noguchi quote where he made clear his autopsy report didn’t imply Sirhan was the lone shooter. That early quote forever fueled conspiracy fires and formed the foundation for those purporting the second gunman claim. On the record, Noguchi always maintained whoever fired the fatal gunshot into Bobby Kennedy was slightly behind him and in very close quarters.

The More-Than-8-Shots Issue

The JNS doctors steered clear of this positioning can of worms. Rightfully so. This wasn’t their field of expertise. That evidence belongs in the police and forensic investigation wheelhouse. Arm-chair detectives with a half-century of hindsight picked the position puzzle apart from every angle. So they’ve done with the number of shots.

Essentially, the Los Angeles police investigators accounted for eight crime scene bullets. They also tested Sirhan’s .22 caliber, 8-shot revolver and ballistically linked the recovered bullets to Sirhan’s gun—except for the fatal bullet from RFK’s brain. It was too fragmented to identify microscopic striations unique to Sirhan’s firearm.

Essentially, the Los Angeles police investigators accounted for eight crime scene bullets. They also tested Sirhan’s .22 caliber, 8-shot revolver and ballistically linked the recovered bullets to Sirhan’s gun—except for the fatal bullet from RFK’s brain. It was too fragmented to identify microscopic striations unique to Sirhan’s firearm.

Most of the “evidence” for the more-than-8-shot theory came from news media reports focused on a photo apparently displaying two bullet holes in a door frame in the Ambassador kitchen. Conspiracy theorists used the logic that if eight bullets were already accounted for, then two extra holes formed positive proof of a second gunman. After all, Sirhan’s revolver contained 8 empty shell casings. He did not have time to reload.

Conspiracy theorists also rely on varying eye and ear witnesses to support their more-than-8-shot suspicions. Many in the kitchen reported hearing 10, 12 and as many as 15 shots blasting off. The RFK case even took a scientific sound step where a media recording allegedly taken during the assassination captured the shots on audio. Various forensic experts extensively analyzed the audio but can’t conclusively agree there were more than 8 shots fired.

There’s a rabbit hole of hints, innuendo and suggestions of extra shots out there in the RFK assassination world. But, there’s one true fact not resolved by the official investigation. That’s that the fatal fragments from RFK’s brain have not been forensically linked to Sirhan’s revolver. It leaves the suspicion door open that it’s physically possible for a second gunman being involved.

Nowhere in the documented RFK assassination evidence is there any reference to forensic authorities trying other tests on the brain bullet fragments than examining for microscopic striations. Bullet lead composition analysis (BLCA) and neutron activation analysis (NAA) techniques were available in 1968. In fact, the John F. Kennedy assassination investigators employed both scientific processes. BCLA and NAA became a ballistic cornerstone establishing Lee Harvey Oswald as JFK’s lone assassin.

Every experienced forensic investigator realizes that BLCA and NAA analysis are indicative or exclusive tests rather than conclusive evidence like tool markings left by firearm rifling engravings. That means running BLCA and NAA tests on RFK’s brain fragments and comparing them to groups analyzed from the known Sirhan bullets would either eliminate or associate them as originating from the same ammunition source.

Unfortunately, there’s no record of anyone conducting these two important forensic examinations. Assuming the RFK bullet exhibits are still available, there’s no reason they couldn’t be done today. That could establish or further rule out the second gunman theory. But, there’s no apparent appetite for any official review, regardless of requests from Kennedy family members to reopen the case.

Sirhan Bishara Sirhan’s Background and Motive

Every homicide investigation team looks at their suspect’s motive and associates. It’s always necessary to establish or rule out accessories to the crime. The RFK murder is no different for investigating who Sirhan was, why he did it and if he had help.

Sirhan originated in the Middle East’s Palestinian region. He was a Christian, not a Muslim as many believe. Sirhan immigrated to America in 1956 when he was 12. His family settled in Pasadena, California where he matured. Little in Sirhan’s history shows him as a potential political assassin.

Sirhan originated in the Middle East’s Palestinian region. He was a Christian, not a Muslim as many believe. Sirhan immigrated to America in 1956 when he was 12. His family settled in Pasadena, California where he matured. Little in Sirhan’s history shows him as a potential political assassin.

Investigation after RFK’s murder found Sirhan’s diary which was full of apparently psychotic references repeating “Bobby Kennedy Must Die”. It seems Sirhan, in some twisted way, fixated on killing RFK and sought an opportunity. That presented at the 1968 Democratic convention when Sirhan simply walked into the Ambassador kitchen through an unlocked door, hung around and then opened fire.

Nothing in Sirhan’s background found him politically linked or motivated by terrorist agenda. He seemed an immigrant Arabic lone wolf version of the All-American psychopath. Like Oswald, Sirhan gained fame by shooting someone famous.

Sirhan was a rubber ball of confessions, recantations and failed recollections. Initially, Sirhan told police investigators he shot RFK because of Kennedy’s policy of arming Israelis with Phantom fighter jets to bomb Palestinian people. At trial, Sirhan denied this motive but admitted being the shooter. Later, he totally recanted his testimony. Over the decades, Sirhan molded himself into a self-serving position of failed memory due to some form of external hypnosis influence during RFK’s shooting.

One thing’s consistent about Sirhan’s statements. Although his motive remains questionable, he never outwardly accused anyone of being his accomplice. Sirhan never said there was a second gunman—at least to his knowledge. He leaves it to conspiracy theorists and authorities to explain inconsistencies like the number of shots fired, the gunshot residue, the distance from the muzzle to RFK’s skin and the relative positions while Bobby Kennedy was shot.

Reconciling the RFK Assassination Discrepancies

And, every murder investigation has evidentiary discrepancies being tough to reconcile. There’s no reason RFK’s assassination should be the exception. Experienced homicide investigators understand a value found in Occam ’s Razor. That’s the age-old problem-solving principle—when presented with competing hypothetical answers to a problem—one selects the answer making the fewest assumptions. Usually, the simplest answer to reconciling a discrepancy is the best and proper answer.

The JNS review panel dealt with Sirhan’s position relative to Bobby Kennedy’s gunshot entrance wounds with a simple observation. While eyewitnesses varied about distances between the shooter and victim, they agreed on body positions. Yes, Sirhan was to the west and ahead of RFK, but Kennedy was turned to his left, exposing his right side to Sirhan. The right side and behind the ear hits were a matter of predetermined physical geometry. So was the apparent upward angle of the fatal brain shot. Kennedy was aside of Sirhan and bent over talking to a busboy.

The JNS reviewers were cautious about distance reports. They note Noguchi made no distance reference in his postmortem exam report. He only verified gunshot residue presence on RFK’s skin and hair. It’s later media recorded comments from Noguchi that committed his estimating an RFK muzzle distance of 3 or less inches.

Again, Occam’s Razor applies to assess Noguchi’s statements. Although Dr. Noguchi was an experienced pathologist, he wasn’t necessarily an expert in GSR distances and patterns. Noguchi’s credibility has to be questioned in this case. He had a reputation as being an egotist thriving on his fame as the “coroner to the stars”.

Again, Occam’s Razor applies to assess Noguchi’s statements. Although Dr. Noguchi was an experienced pathologist, he wasn’t necessarily an expert in GSR distances and patterns. Noguchi’s credibility has to be questioned in this case. He had a reputation as being an egotist thriving on his fame as the “coroner to the stars”.

Thomas Noguchi performed autopsies on celebrities like Marilyn Monroe, Natalie Wood, John Belushi and Sharon Tate. Some suggest Noguchi loved the limelight and extended his realm of expertise with unqualified opinions. Interpreting gunshot residue patterns may be beyond Noguchi’s talent. He might simply be wrong about estimating GSR discharge distance in RFK’s case.

Plenty of forensic science literature in murder investigations show GSR patterns present from muzzle distances of 1 or more feet. There’s no reason GSR from a short-barreled .22 Iver Johnson revolver couldn’t have produced stippled powder burns on RFK’s skin and hair from several feet away. Note the only link with the RFK-GSR second gunman theory comes from Noguchi’s belated media opinion. There’s no other source qualifying maximum muzzle measurement.

With gunshot angles and distance discrepancies reasonably rectified, the only remaining trouble area is the number of shots fired. Again, all RFK crime scene investigation evidence accounts for 8 fired bullets. There’s no credible case for more than 8 shots in RFK’s murder. There’s only speculation based on unsupported information.

Applying Occam ’s Razor to conspiracy theories in Robert F. Kennedy case concludes Sirhan Sirhan fired all shots. He acted alone without an accomplice. There’s no credible evidence otherwise, and that’s because non-events leave no evidence. It never happened any other way.

There was no second gunman in the RFK assassination.