Creative writing stands upon two concrete, foundational pillars. Ideas and information. As a metaphor, information is cement and ideas are the mixer. You can’t build a story or construct an article without either. And there’s a long-used tool that lets you blend ideas and information within one toolbox. The box contains scraps of wisdom—keeping a commonplace book.

Creative writing stands upon two concrete, foundational pillars. Ideas and information. As a metaphor, information is cement and ideas are the mixer. You can’t build a story or construct an article without either. And there’s a long-used tool that lets you blend ideas and information within one toolbox. The box contains scraps of wisdom—keeping a commonplace book.

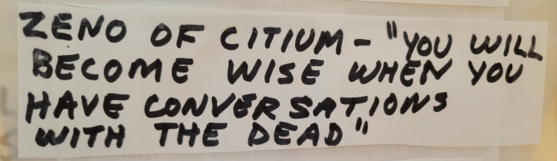

Just as it sounds, it’s storing your scraps of ideas and bits of information in one common place. This creative support isn’t new. It’s been used over the millennia by great thinkers and writers like Marcus Aurelius, Leonardo da Vinci, Charles Darwin, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Virginia Woolf, Ayn Rand, John Locke, H.P. Lovecraft, Mark Twain, and Isaac Newton to name a few. Many creatives today retain a commonplace to fuel and inspire them, and many swear it’s their main receptacle of wisdom.

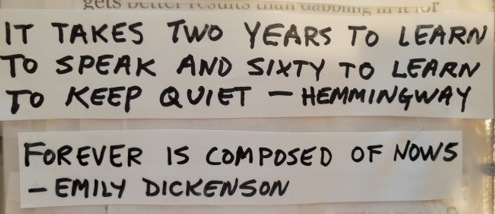

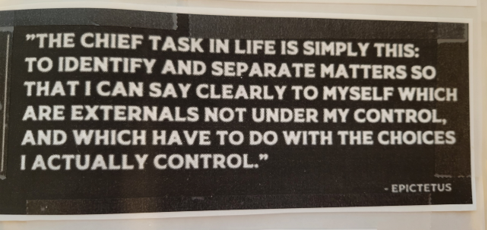

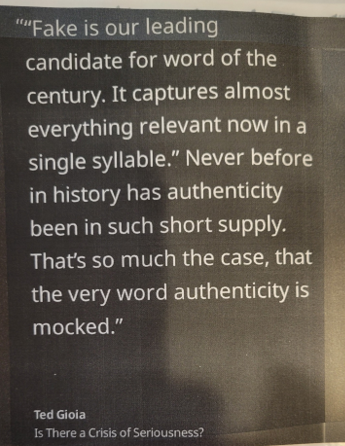

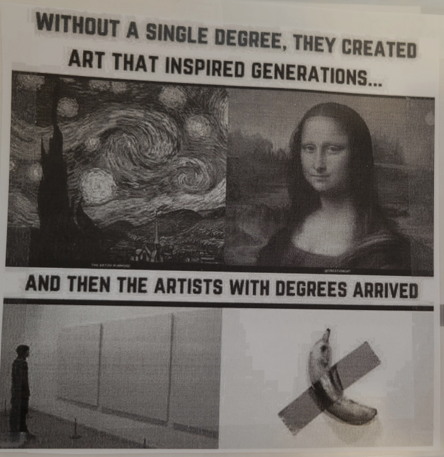

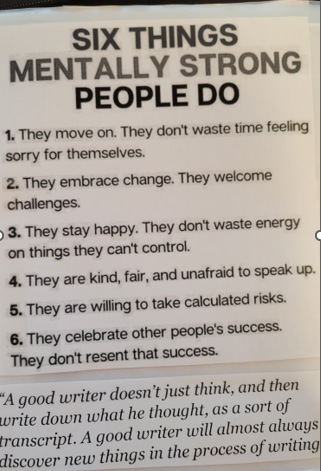

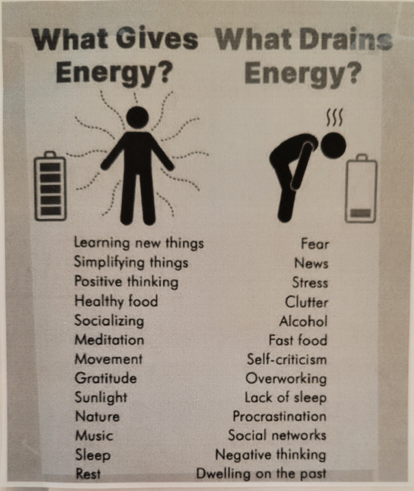

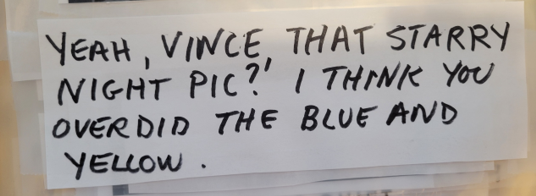

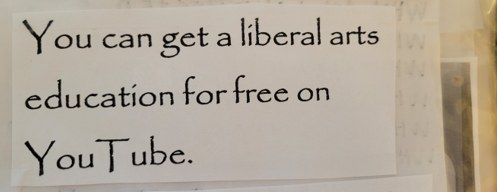

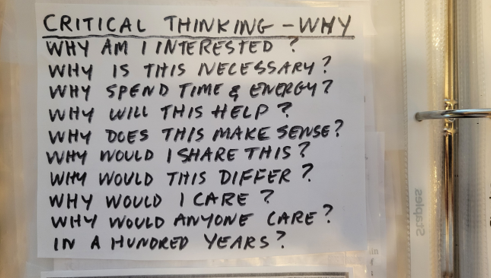

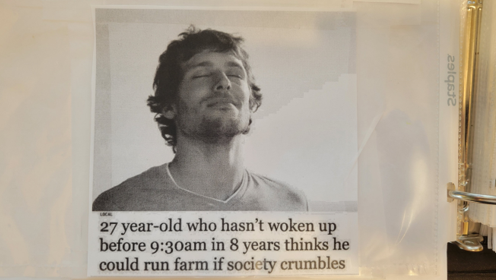

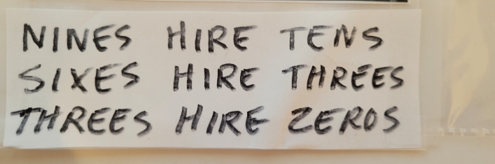

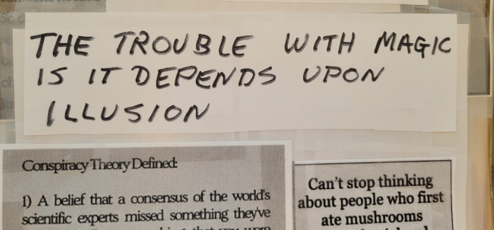

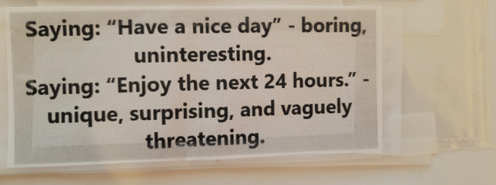

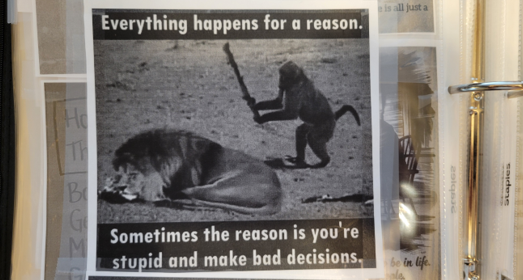

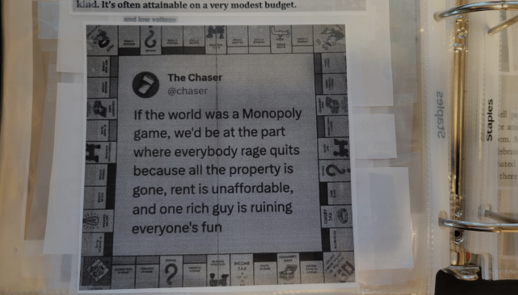

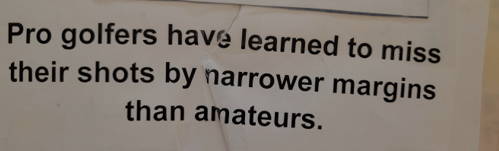

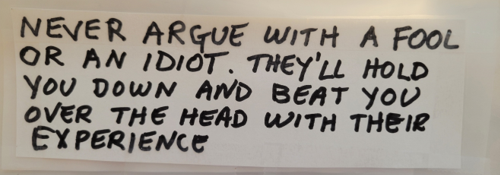

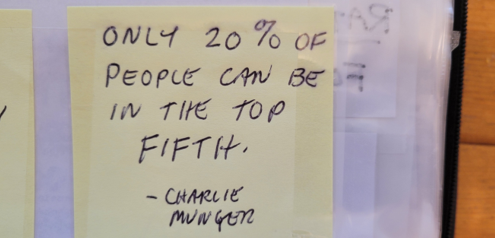

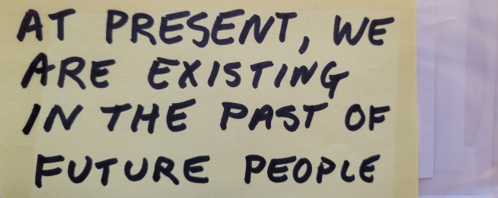

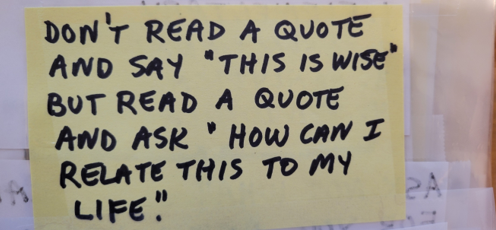

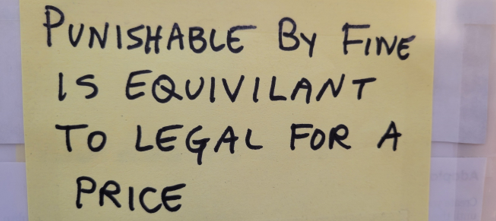

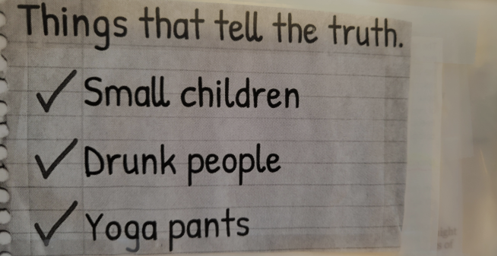

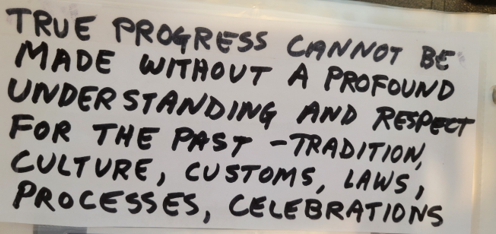

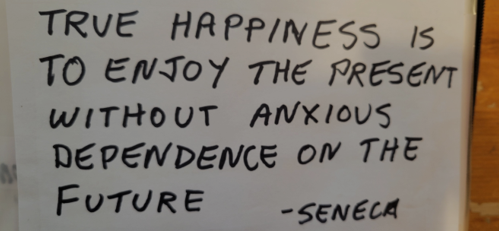

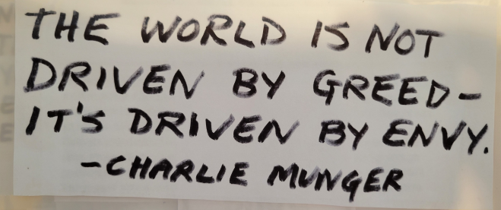

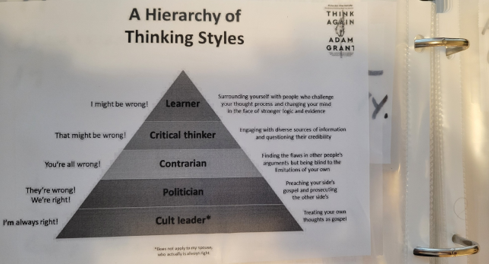

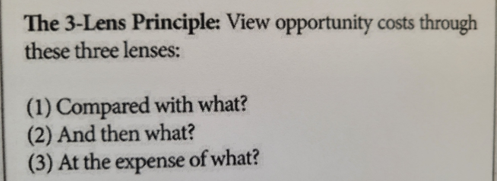

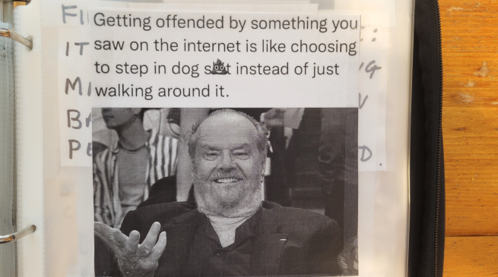

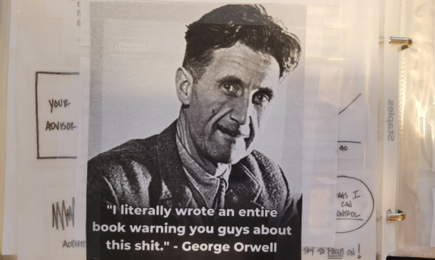

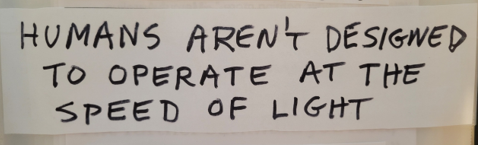

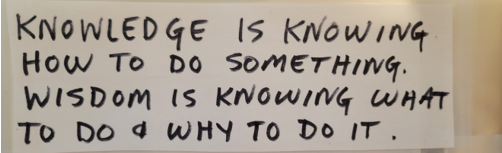

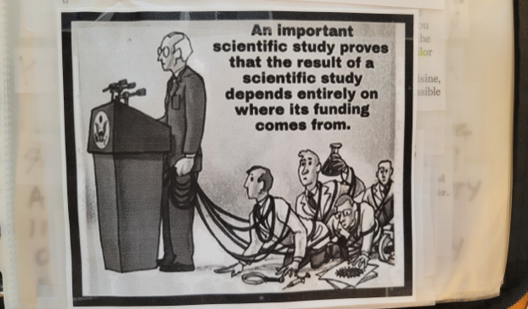

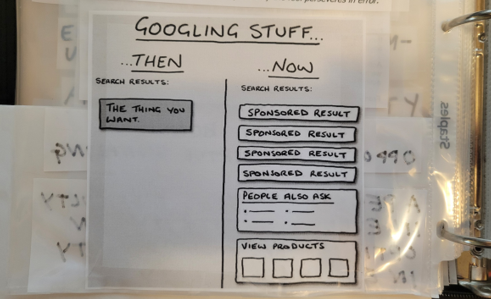

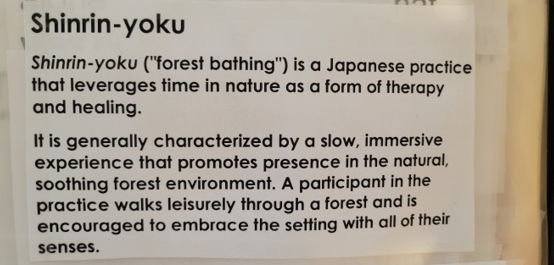

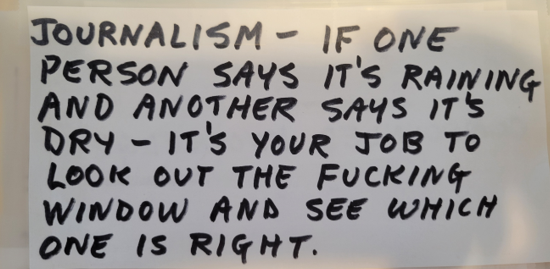

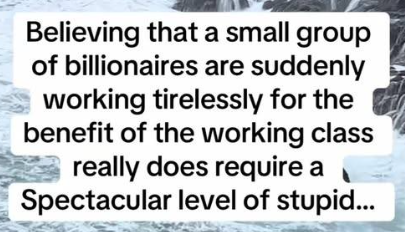

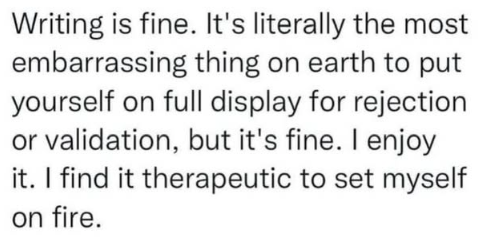

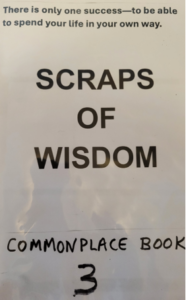

I started the DyingWords blog thirteen years ago. After creating five hundred posts, writing twenty-one book publications, and penning several thousand content pieces for commercial websites, my commonplace book has grown into three volumes cut & pasted full of quotes, sayings, anecdotes, observations, jokes, memes, proverbs, prayers, affirmations, formulas, sermons, remedies, pictures, drawings, topics, discoveries, examples, situations, comments, captures, notes, insights, lyrics, phrases, and even recipes. All are little scraps that arise through information and maybe will morph into big ideas.

I’m going to open my commonplace book and show you a random selection of what’s inside. You never know, you might find a takeaway you can build upon. First, let’s look at the big picture of what commonplace books are. And, equally important, what commonplace books are not.

The best descriptor I could find of a commonplace book is a Personal Knowledge Management System. If you Google “commonplace book” or ask ChatGPT, you’ll find oodles of links and helpful tips on a centralized, personally curated, and continuously maintained collection can be—personally curated being the operative phrase. This is not the sort of database you can buy at Staples (although you can buy binders like I use for mine).

At the core, your commonplace book is like a strainer. It’s a tool for storing and sifting whatever you come across that seems interesting, pertinent, or might come handy in the future. By the way, you don’t have to be a creative writer to keep a commonplace. It works for recipes, sports cards, dried insects or leaves, bus tickets, celebrity autographs, and even biological samples if you’re into it.

Seriously, commonplace books are private spaces for private thoughts. They are not daily logs, narrative journals, to-do lists, or drafts of work-in-place. Commonplace books are simply scrapbooks but generally lean toward one theme. In my case, they contain ideas and information I can use to develop projects and better understand the world.

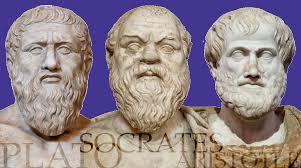

The word “commonplace” traces back to ancient Greece where a law courts speaker or politician would keep an assortment of arguments in a “common place” for easy reference. The Romans called them locus communis meaning “a theme or argument of general application” such as a statement of proverbial wisdom. But the commonplace book would only come into its own during the European Enlightenment when an exploding volume of printed media collided with changing political and societal norms. Commonplace books provided a private place for people to note information and store it to help work out thoughts and ideas.

In 1706, philosopher John Locke described his archival process in a book titled A New Method of Making Common-Place-Books. This set the standard for what would become a mainstream storage and organizational system that allowed their keeper to act in the external world more effectively by isolating truly important material. In Locke’s words and vernacular of the times, We extract only those Things which are Choice and Excellent, either for the Matter itself, or else for the Elegancy of the Expression, and not what comes next.

A fundamental structure of commonplace books is they’re not structured in any order—not a flowing or chronological narrative such as recording in a personal journal. Rather, they’re a random collection of come-across snippets that relate to the beholder and are meaningful in some or many ways.

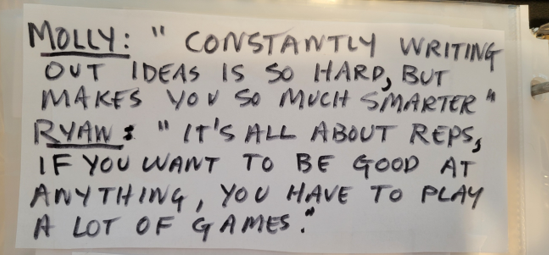

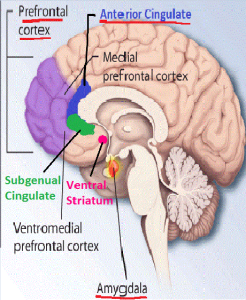

Most creatives understand the value in writing down ideas. There’s a cognitive link between discovering information and transposing it by hand to a page. Capturing and retaining words and images then storing in in a repository frees up mental horsepower for thinking and creating. Material in a commonplace book becomes an extension of the mind—a backup of what can be profound as a personal compass or a guide—a mental sketchbook.

I’ll relate my personal story of developing a commonplace book. Ten years ago, I was working with my writing mentor. That was back before he was famous, and I still had some color in my hair. He asked, “Do you keep a commonplace book?” I replied, “What’s that?” He said, “It’s a scrapbook where you store bits of wisdom for future reference and motivation.”

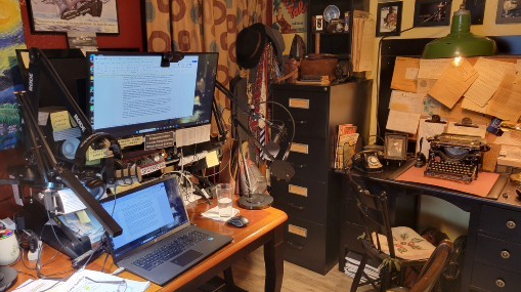

That hit home about putting my scraps of wisdom into a book. Till then, I had yellow, sticky Post-it notes stuck about my studio. I had pictures and photocopies and cut-outs and banners of relevant stuff here and there and all over the place. It was a mess and growing messier by the week.

I’m not sure where the idea came from, but I went to Staples and bought a three-ringed binder and some clear sheet protectors along with a roll of Scotch tape. For what seemed like hours, I peeled and pasted my relevant stuff onto the sheets and made sure there was no particular order—just a random bunch of, well, relevant stuff.

It’s now grown to three binders and nearly ready for a fourth. Usually, I see an image or a quote on the net or in my email and I either screenshot or highlight it, transfer into a Word.doc, print it, and then simply scissor it out and tape it onto the clear sheet. It’s just like playing with paper dolls.

I’m not saying my binder method is right for you or anyone else. I’ve read that others use index cards. Some store digitally. And a few use a plain old notebook. Whatever works to store and retrieve your scraps of wisdom.

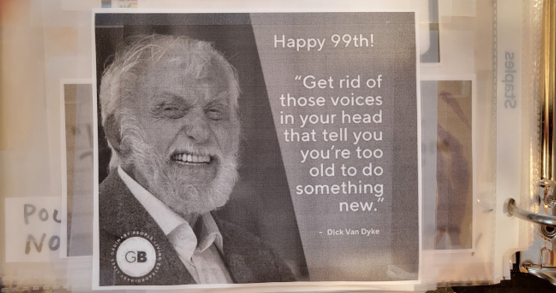

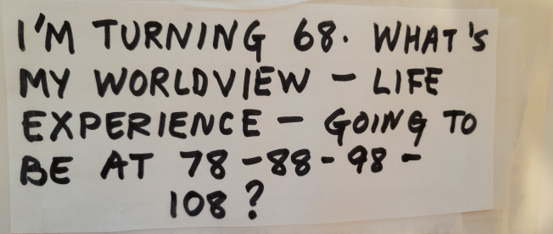

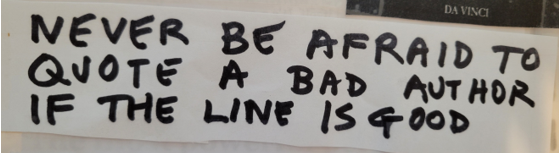

Enough about this. I’m sure you’d like to snoop through my three commonplace volumes. Welcome to my writing and recording studio. Here’s some random snips!