Many people view wildlife trophy hunting as morally indefensible. They consider it abhorrently unethical to kill wild animals for sport and display their body parts as testaments to testosterone, despite economic implications. Then, there are those who support trophy hunts, defending it as a rite of passage, a way of preserving cultural heritage and a massive money maker. For both sides, the trophy hunt debate is emotional.

Many people view wildlife trophy hunting as morally indefensible. They consider it abhorrently unethical to kill wild animals for sport and display their body parts as testaments to testosterone, despite economic implications. Then, there are those who support trophy hunts, defending it as a rite of passage, a way of preserving cultural heritage and a massive money maker. For both sides, the trophy hunt debate is emotional.

Although trophy hunting might not be ethical to most, it’s still legal in many countries. Trophy hunts are prominent in Africa and North America. They bring in a lot of money to local economies. So does wildlife ecotourism and the ability to shoot a majestic animal countless times with a camera while doing no harm.

The debate over wildlife trophy hunting isn’t going away. Recently, the State of Wyoming allowed a limited entry kill-hunt for a quota of 22 grizzly bears on the fringe of Yellowstone Park’s boundaries. That’s not just for mature males. It’s legal to slay a pregnant female and stuff her as your rug. Meanwhile, the Province of British Columbia finally banned grizzly bear hunting except for allowing indigenous people their ceremonial harvest.

High profile trophy kills get opponents riled up. Rightfully so. Killing Cecil the Lion by luring him outside Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park so American dentist Walter James Palmer could drive an arrow through Cecil unleased a hellfire of anti-hunting fury. Then there’s the recent auction where one license to kill a critically endangered black rhinoceros went for $225,000—allegedly with the proceeds going towards protecting black rhinos. Go figure.

High profile trophy kills get opponents riled up. Rightfully so. Killing Cecil the Lion by luring him outside Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park so American dentist Walter James Palmer could drive an arrow through Cecil unleased a hellfire of anti-hunting fury. Then there’s the recent auction where one license to kill a critically endangered black rhinoceros went for $225,000—allegedly with the proceeds going towards protecting black rhinos. Go figure.

I’ve seen both sides of the trophy hunting fence. Over the years, I’ve matured. I used to support trophy hunting. Now I take the position wildlife trophy hunting is no longer justified under any circumstances. In my opinion, that includes native ceremonial hunts. However, I do support subsistence hunting, legitimate sport hunting where non-threatened animals are taken for food and culls where invasive species need eradicating to maintain a balanced ecosystem.

I haven’t always been this opposed to trophy hunting. Far from it. Shamefully, I admit—I used to trophy hunt. Before analyzing the economics, ethics and emotions surrounding the trophy hunt issue, let me tell you my background, why I once trophy hunted and why I changed my ways.

I was raised in the Whiteshell Park in southeastern Manitoba, Canada. My father was a mink farmer and ran a trap line for supplemental income. Being brought up in the fur industry, I didn’t see anything wrong with harvesting animals for food and pelts. Our mink were euthanized humanely, and my dad abhorred leg-hold traps, using quick-kill Conibears instead. It was our livelihood as it was for many people in our community.

I was raised in the Whiteshell Park in southeastern Manitoba, Canada. My father was a mink farmer and ran a trap line for supplemental income. Being brought up in the fur industry, I didn’t see anything wrong with harvesting animals for food and pelts. Our mink were euthanized humanely, and my dad abhorred leg-hold traps, using quick-kill Conibears instead. It was our livelihood as it was for many people in our community.

The thought of killing an animal for sport or having a trophy never entered my mind as a kid. My dad didn’t do it. Neither did our neighbors. But times changed in my teens, and the local economy switched from subsistence harvesting to supporting trophy hunts for large game like moose, deer and black bears. That’s because fur prices tanked due to anti-trapping movements. To survive, country folk began guide-outfitting big game, cashing-in on wealthy city-slickers and American adventurers’ egos.

I joined Canada’s national police force at 21. I was posted to British Columbia which is a trophy hunter’s mecca. But now, I was starting to have mixed feelings about subsistence vs. trophy hunting ethics. Deep down, something wasn’t right.

My trophy hunting phase ended when I got a mountain goat tag and climbed to lofty heights to get the drop on a Billy. Mountain goats normally look down for threats, not up. Sure enough, I skillfully and stealthily stalked from the top and got him in my crosshairs. I set my finger on the trigger, started the squeeze… then stopped. “Bang”, whispered my mouth. I slipped the safety on, set my rifle aside and spent the next half hour watching this beautiful creature peacefully go about his God-given business.

My trophy hunting phase ended when I got a mountain goat tag and climbed to lofty heights to get the drop on a Billy. Mountain goats normally look down for threats, not up. Sure enough, I skillfully and stealthily stalked from the top and got him in my crosshairs. I set my finger on the trigger, started the squeeze… then stopped. “Bang”, whispered my mouth. I slipped the safety on, set my rifle aside and spent the next half hour watching this beautiful creature peacefully go about his God-given business.

Unfortunately, I didn’t have a camera. But the memory of watching that goat graze and navigate the rock face indelibly etched my mind. It’s still far, far more rewarding—not economically, but ethically and emotionally—to envision that goat rather than having his head on my wall. I wish every trophy hunter could have that Euphemia.

I never trophy hunted again. But, I did go on the biggest, big game hunt imaginable. This one changed my life forever. I was part of an Emergency Response Team sent to capture a deranged and murderous madman terrorizing the Canadian north. He had the cunning of an animal, the intelligence of a human, was on his own turf and was armed with a rifle. Plus, he had every intention of hunting us down and killing us. Sadly, he fatally shot my partner and almost got me. I was forced to put him down.

After that, I never went hunting again. I’ve even stopped fishing and would rather put a spider outside. I had another life-changer a few years ago when I reinvented careers and took a job guiding eco-tourists from around the world to see grizzly bears and whales on the British Columbia coast. These wealthy adventurers paid over $2,000 per day to shoot creatures with cameras. To think grizzlies were legally killed for personal pleasure was absolutely abhorrent to them—and to me.

After that, I never went hunting again. I’ve even stopped fishing and would rather put a spider outside. I had another life-changer a few years ago when I reinvented careers and took a job guiding eco-tourists from around the world to see grizzly bears and whales on the British Columbia coast. These wealthy adventurers paid over $2,000 per day to shoot creatures with cameras. To think grizzlies were legally killed for personal pleasure was absolutely abhorrent to them—and to me.

That brings my opposition to trophy hunting full circle. I can’t support this practice from an economical, ethical or emotional point. Looking back, I struggle with why some people still enjoy slaughtering an animal for their ego. Maybe they need to grow up—like I had to.

So where did this trophy hunting mentality come from? It’s been around a long time. Creating relics from animal body parts dates back to ancient societies. “Trophy” comes from the Greek word tropian which means to defeat. Historically, trophies like scalps and appendages were collected as fetish emblems of conquest to convey warrior or hunter prowess of power, strength and status.

It’s one thing to wage war on other humans and conquer enemies in the name of self-preservation. It’s also another thing for humans to harvest animals as subsistence in providing food and clothing. But there’s something ethically twisted about humans elevating themselves above the “lesser” animal kingdom where displaying their severed body parts as collectables, souvenirs and oddities somehow shows a hunter’s status.

Trophy hunters have a distinct profile. Predominantly, they’re conservative white males of European or North American descent. Most are wealthy men of privilege who have the time and money to undertake this expensive and lengthy pursuit. In almost all jurisdictions, licensed trophy hunters must hire guides. They also charter planes, boats and stay in luxury lodges. As well, they buy expensive rifles and wear the best hunting gear from Cabelas.

Trophy hunters have a distinct profile. Predominantly, they’re conservative white males of European or North American descent. Most are wealthy men of privilege who have the time and money to undertake this expensive and lengthy pursuit. In almost all jurisdictions, licensed trophy hunters must hire guides. They also charter planes, boats and stay in luxury lodges. As well, they buy expensive rifles and wear the best hunting gear from Cabelas.

Trophy hunting supporters shy from the ethical argument and rely on the economics. Statistics are tough to support, especially with the trickle-down analogy, but it’s safe to say many trophy hunters shell out $20,000 or a lot more for their chance to assassinate an animal. No doubt, that’s a lot of money going into an economy—especially if it’s a poorer part of Africa or a northern First Nations community.

You can make the same economic argument about camera shooting. Eco-tourism is a rising economic engine in Africa and North America. Right now, I have friends on an African Safari and just looked at their Facebook photos of giraffes and elephants. Tomorrow, they’re camera hunting lions and I look forward to seeing their very expensive pics of the big cats, too. Canadians Melissa and Ed are injecting big bucks into the African eco-tourism economy.

Then, there’s the economic argument of raising money for conservation through trophy hunting. I call bullshit on this one, too. I’m quoting Miles Moretti, president of the Mule Deer Foundation in Utah where his group raised $200,000 from mulie tags. Moretti says, “Can a guy buy a tag every year? Yes, if he’s got the money. So what if it’s not fair. Well, life’s not fair. This is a way to raise money for wildlife.” What Moretti avoided telling the investigative reporter is that most of the 200 thousand dollars went to fund politicians supporting the NRA and the Safari Club International. The rest went to lobbyists wanting a wolf kill so they’ll be more mule deer to trophy hunt.

Then, there’s the economic argument of raising money for conservation through trophy hunting. I call bullshit on this one, too. I’m quoting Miles Moretti, president of the Mule Deer Foundation in Utah where his group raised $200,000 from mulie tags. Moretti says, “Can a guy buy a tag every year? Yes, if he’s got the money. So what if it’s not fair. Well, life’s not fair. This is a way to raise money for wildlife.” What Moretti avoided telling the investigative reporter is that most of the 200 thousand dollars went to fund politicians supporting the NRA and the Safari Club International. The rest went to lobbyists wanting a wolf kill so they’ll be more mule deer to trophy hunt.

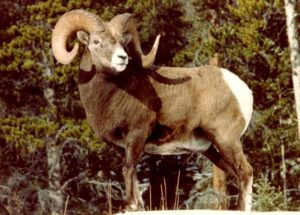

Pro-trophy hunters always bring up an “ethical” defense where they claim only mature males of a species are harvested. This follows the reasoning these old guys are past their breeding prime despite displaying healthy hides and horns. Therefore, there’s no harm to the overall species. In fact, they claim, this distributes the gene pool more efficiently as it gives the younger males a chance to sow seed.

That argument doesn’t wash, if you listen to University of Washington professor Rob Wielgus who is the director of the Large Carnivore Conservation Laboratory. Despite trophy hunting proponents throwing out deceptive terms for wildlife management like metrics, population estimates, harvestable-surplus and acceptable kill-quotas, Wielgus provides scientific proof that old males are especially critical as apex predators.

He’s studied big bears and big cats since 1982 and has indisputable evidence that when trophy hunters kill dominant apex predator males, the younger males aren’t up to the replacement job. Killing mature and dominant males sets off a chain of events, according to Wielgus. New immigrant males move to the territory and kill infant animals to bring mature females back into estrus. This not only decimates future breeding stock, it forces fleeing females into populated areas where their feeding habits change. That conflicts with humans, and these nuisance animals are euthanized.

He’s studied big bears and big cats since 1982 and has indisputable evidence that when trophy hunters kill dominant apex predator males, the younger males aren’t up to the replacement job. Killing mature and dominant males sets off a chain of events, according to Wielgus. New immigrant males move to the territory and kill infant animals to bring mature females back into estrus. This not only decimates future breeding stock, it forces fleeing females into populated areas where their feeding habits change. That conflicts with humans, and these nuisance animals are euthanized.

According to Wielgus, “Basically, the new guy finally establishes a territory and then he gets killed and the whole thing starts over again. So you don’t end up with more or fewer carnivores. What you have is a bunch of teenage carnivores wreaking havoc on the system and a bunch of dead cubs and starving females.”

According to representatives of the Safari Club International, trophy hunting is an honorable and prestigious money maker. That alone, according to this exclusive men’s club, justifies the practice. They make no bones that economic resources are the primary factor for a trophy hunter to buy their way into recognition with one of their coveted awards like the Africa Big Five Award.

Hunters who can afford trips, guides and equipment have the exclusive ability to bag lion, leopard, rhino, elephant and cape buffalo and rise to the top of the trophy hit list. Because not everyone can afford repeated African safaris nor is in physical condition to hunt in the wild, now a trophy hunter can qualify for the Big Five by hunting lions and cape buffalo raised in captivity on American game farms. You can even hunt from a wheelchair—as long as you show them the money.

These game farms are called “canned hunting”. Trophy hunters who legitimately face the wilds by hiking or on horseback spending days on a stalk and passing on inferior animals claim their success comes from stealth and stamina. That is the mark of an excellent hunter. I argue that’s also the mark of an excellent photographer, but you can’t bring that reasoning into canned hunts.

These game farms are called “canned hunting”. Trophy hunters who legitimately face the wilds by hiking or on horseback spending days on a stalk and passing on inferior animals claim their success comes from stealth and stamina. That is the mark of an excellent hunter. I argue that’s also the mark of an excellent photographer, but you can’t bring that reasoning into canned hunts.

Canned hunting only requires money. There’s no patience or ethical restraint in this game. Canned hunters use the most expedient methods of execution available. They show egocentrism, display impulsive behavior and seek immediate gratification. Take the case of former U.S. Vice-President Dick Cheney who trophy hunted canned pheasants. One weekend, Cheney and friends bagged 417 farm-raised ringnecks. Cheney, himself, dropped 70 birds before accidentally shotgunning his hunting partner. In a clear case of over-eagerness to kill, Cheney seriously violated basic gun safety rules. He’s lucky he wasn’t charged with the dangerous use of a firearm.

Justifying trophy hunting from an economic reasoning is a thin argument. You can make exactly the same case by promoting eco-tourism where a hunter trades his rifle for a camera. Yes, it’ll harm the taxidermy business, but there’s always a loser when times change, and people always adapt to different values and mindsets.

And that’s what trophy hunting is—a mindset. It’s a bygone, barbaric act from an archaic era. There’s no need to have animal parts mounted on a trophy room wall. The same effect is nicely done with framed photos. Trophy hunting is a contrived want that falsely presents a Euro-American way. It’s a way that should be gone forever.

And that’s what trophy hunting is—a mindset. It’s a bygone, barbaric act from an archaic era. There’s no need to have animal parts mounted on a trophy room wall. The same effect is nicely done with framed photos. Trophy hunting is a contrived want that falsely presents a Euro-American way. It’s a way that should be gone forever.

I no longer buy the economic issue. I support the ethical stand that trophy hunting should stop while eco-hunting takes over. It takes as much skill—possibly more—to stalk wild animals and get a clear camera shot at them.

Ending live-kill trophy hunting is an economical, ethical and emotional discussion. It’s the emotions of a macho-man weakly demonstrating his right to bear arms against a defenseless animal. It’s also the emotions of passion people who ethically oppose trophy hunting by reaching out to their lawmakers. The people of British Columbia did that. On ethical grounds—not economic— they emotionally appealed to their legislature and got the grizzly kill stopped. That macho era is over in B.C.

In my opinion, there’s nothing manly about paying 10 grand for a guided hunt so an egotist can shoot a baited black bear from 50 yards with his .338 Lapua Magnum equipped with a 10X scope nicely rested on a bipod. If he truly wants trying something macho, he should strip buck-naked, jump in and go after a crocodile with a Bowie knife gripped in his teeth.