You’d think you’d know all the best crime stories of your hometown, especially when you were a police officer there and spent most of your service on the Serious Crimes Section—being a murder cop. Specifically, true crime stories of this magnitude which turned out to be one of the most complex double homicide investigations in your city’s history. But, no, I’d never heard of this case until I was sitting in my barber’s chair the other day and Dave told me about the maniac murders at Lovers Lane.

You’d think you’d know all the best crime stories of your hometown, especially when you were a police officer there and spent most of your service on the Serious Crimes Section—being a murder cop. Specifically, true crime stories of this magnitude which turned out to be one of the most complex double homicide investigations in your city’s history. But, no, I’d never heard of this case until I was sitting in my barber’s chair the other day and Dave told me about the maniac murders at Lovers Lane.

Dave Lawrence is Nanaimo’s downtown barber. Dave runs a one-man show at That 50s Barber Shop on Victoria Crescent where multi-millionaires push past shopping cart vagrants to get the best haircut in town. Also to find out what’s going on in town because, if you want to know, Dave’s the go-to guy for knowing what’s going on around town.

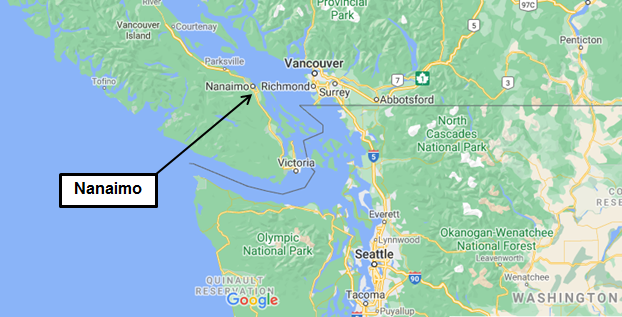

Nanaimo, by the way, is a city of 100,000 on the southeast side of Vancouver Island in British Columbia, Canada. It’s right across the water from the City of Vancouver which is one of the most exotic, erotic, and expensive places on our planet. Nanaimo is laid back in many ways, but it has an abnormally high per capita murder rate. And it’s been my home for the past thirty-four years.

I went into Dave’s shop last Saturday to get all four sides trimmed. We got talking, as we always do, and he goes, “Garry, you were a cop for a lot of years here in Nanaimo. Ever hear about the maniac murders at Lovers Lane?” I says, “No, Dave. You been smoking crack again like that guy who just tweaked by your window?” So Dave goes, “Seriously, dude. This really happened, and it’s the best true crime story I ever heard of.” Then Dave tells me about the maniac murders at Lovers Lane.

This true crime story doesn’t start with the cold-blooded executions of two young lovers. It starts fourteen years earlier on May 31, 1948, with a railroad washout near Kamloops in British Columbia’s interior. That spring, flooding was intense and the rushing water undermined a trestle pier holding up a bridge section where the Canadian National Railroad crossed the Thompson River. The bridge collapse took with it the telegraph lines connecting communications between western Canada and the east.

This true crime story doesn’t start with the cold-blooded executions of two young lovers. It starts fourteen years earlier on May 31, 1948, with a railroad washout near Kamloops in British Columbia’s interior. That spring, flooding was intense and the rushing water undermined a trestle pier holding up a bridge section where the Canadian National Railroad crossed the Thompson River. The bridge collapse took with it the telegraph lines connecting communications between western Canada and the east.

Losing a bridge section was one thing. Destroying communications was another. The only thing holding the main telegraph line from snapping under the weight of a sagging bridge was a small wooden bracket holding a glass insulator that the wire held fast to.

Leave it to railroader ingenuity. One sectionman got the idea to shoot the wire free. He borrowed the station agent’s .22 rifle, lay on the bank, and plinked away until he broke the bracket and saved the day. The rifle went back to the station agent’s house and was forgotten.

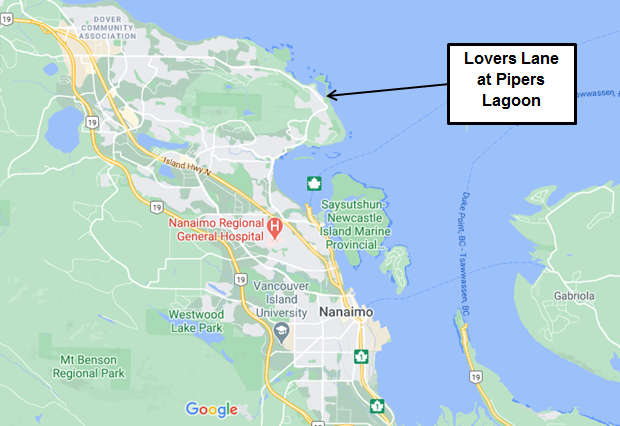

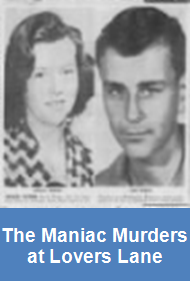

Until October 16, 1962. That’s when pretty nineteen-year-old Diane Phipps went on a date with her handsome boyfriend of six months, nineteen-year-old Leslie Dixon. That evening, the pair drove about downtown Nanaimo—then a city of around 20,000—stopping at the drive-in, gabbing with friends, and generally being young people in love. After dark, Diane and Leslie drove way out to Pipers Lagoon which the youths of Nanaimo called Lovers Lane. They parked and began to make out and were never seen alive again.

Pipers Lagoon is about eight miles from downtown Nanaimo. It’s in the Hammond Bay area which is now full of upscale homes but, thankfully, the city wisdom at the time foresaw the value of Pipers Lagoon and preserved it as parkland. It’s a strikingly beautiful spot, even though it has this history.

Pipers Lagoon is about eight miles from downtown Nanaimo. It’s in the Hammond Bay area which is now full of upscale homes but, thankfully, the city wisdom at the time foresaw the value of Pipers Lagoon and preserved it as parkland. It’s a strikingly beautiful spot, even though it has this history.

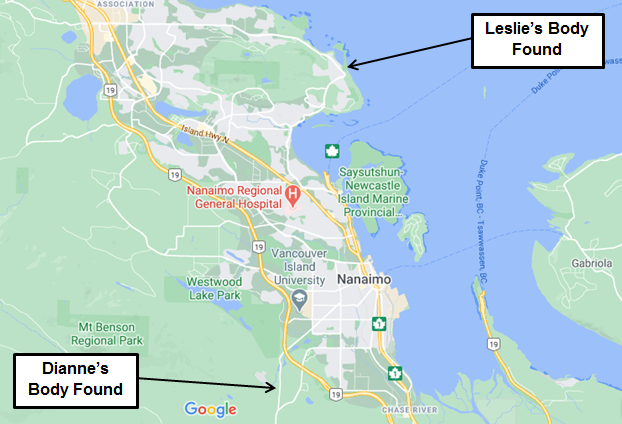

Diane Phipps and Leslie Dixon’s families became concerned—very concerned—when the two lovers didn’t come home by morning. Friends knew they’d likely gone to Lovers Lane, so that was the first place they searched. They found Leslie’s car. It was parked in the lane. He was slumped inside behind the wheel, dead, with two .22 bullets to the back of his head. Dianne was nowhere in sight.

This started the biggest criminal investigation in Nanaimo’s history. How I never heard about it, I don’t know, but Dave steered me to a website that documented the case as well as archives in the Vancouver Sun that covered the story. Here’s what happened.

Crime scene investigators found Leslie had been shot at close range. They surmised that the killer surprised the pair and shot him through an open driver’s side window, leaving his body in place. Leslie’s wallet with money was still in his pocket which indicated robbery was not a motive. There was no blood or evidence of Dianne being shot while sitting on the front passenger side seat, so the police officers surmised she’d been abducted at gunpoint.

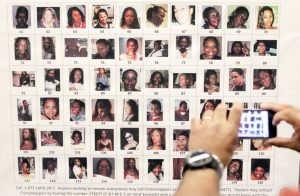

The Nanaimo detachment of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) called in extra resources. A large search of the surrounding area found no trace of anything connected with the crime, including Dianne Phipps. Officers went door to door and investigated the pair’s trail the previous evening. They were baffled and quickly involved the media, asking for public help.

At 2:00 p.m. on the day after Leslie Dixon was found murdered, a Nanaimo resident was rummaging through a rural garbage dump five miles south of Nanaimo in a semi-rural area called Harewood. He saw a pair of feet sticking out from under some old car parts. It was Dianne Phipps. She’d been shot once between the eyes and her head had been bashed-in with a rock. Her time of death was consistent with the early morning hours of October 17.

Dianne wasn’t sexually assaulted. She was fully clothed and her purse, containing money, was beside her. With robbery and sexual overtones ruled out, and no one in the couple’s entire history posing a threat, the RCMP suspected they had a murderous maniac on their hands.

More public appeals went out. Police got a call from a woman who lived on Harewood Road, not far from where Dianne’s body was found. She related that at 1:00 a.m. on the night of the murders she got a knock on her door. A very strange man was there and said his car was stuck in a nearby ditch. He asked if she would take her pickup and pull him out.

She did so. He posed no threat to her, but she found his actions so bizarre that she thought he’d done something else. Now hearing of Dianne’s body being found close to where she towed this stranger, she suspected the incidents were related.

The witness lady gave the police an excellent description of the man and his sedan. She did not get a name, nor did she record the license number. This suspect and vehicle information was widely broadcast and developed hundreds of tips.

Week by week and month by month, the police investigation team put their hearts into the case of the Lovers Lane murders. The City of Nanaimo posted a $5,000 reward which was equivalent to a year’s wages back then. More tips came in, but not the right ones.

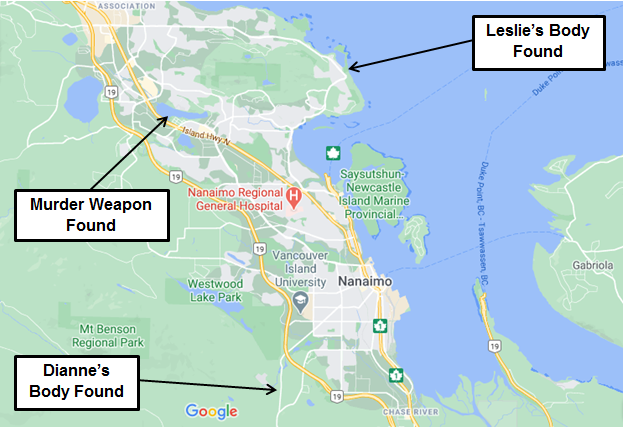

The weather turned as cold as the case. Vancouver Island is normally Canada’s winter hot spot. It rarely freezes on the south island and only snows occasionally. The winter of 1962/1963 was far colder than normal. The local lakes froze to the point where people could walk on the ice which is what a young boy did on Long Lake which is in north Nanaimo miles away from Lovers Lane and the Harewood dump.

The boy saw something through the ice. It was a rifle—a rather unusual rifle. The boy called his father, and they smashed through the ice and retrieved a Winchester Model 63 semi-automatic .22 with serial number 41649A stamped on it.

The father was suspicious as to why someone would throw a valuable firearm in the lake. He took it to the police who sent it to the crime lab. This firearm found in Long Lake matched the .22 bullets taken from Dianne Phipps and Leslie Dixon at their autopsies. It was the murder weapon.

The police held back this information while they pursued other leads. They traced the .22 as being manufactured on October 5, 1940, and was sold by a Kamloops sporting goods store in 1942. However, back then in the Second World War years, purchaser records weren’t kept. The trail again grew cold.

On Saturday, April 18, 1964—almost a year and a half after the murder weapon was found—the Vancouver Sun ran a front-page story and, with police permission, released the holdback information on the unusual firearm along with its photo. This started the tips again.

The sectionman who shot the telegraph bracket and saved the communication day back in 1948 saw the rifle’s photo and strongly suspected it was the one he used that belonged to the station agent, one Robert Ralph Dillabough of Kamloops. There was a problem with that. Mr. Dillabough had died ten years earlier. However, his estate had recorded the rifle as an asset, including it having the serial number 41649A. It was the same piece, for sure.

Diligent detective work took place. Police tracked Dillabough’s estate through a law firm of Mr. D.T. Rogers of Kamloops. They recorded that the murderous .22 was sold at an auction in Kamloops on February 19, 1955. The auctioneer was named George Shelline who they found had been killed in an automobile accident a year earlier. Shelline’s estate had no records of who purchased this puzzling and deadly firearm. Once again, the case went cold.

Diligent detective work took place. Police tracked Dillabough’s estate through a law firm of Mr. D.T. Rogers of Kamloops. They recorded that the murderous .22 was sold at an auction in Kamloops on February 19, 1955. The auctioneer was named George Shelline who they found had been killed in an automobile accident a year earlier. Shelline’s estate had no records of who purchased this puzzling and deadly firearm. Once again, the case went cold.

Over time, the police followed over five thousand tips taking hundreds and hundreds of statements. They checked 60,000 vehicle registrations for the suspicious car that was towed from the ditch along Harewood Road and they checked over 2,000 firearms sales invoices. The RCMP got help from the FBI and from Scotland Yard and from Interpol. They amassed what was the largest murder file in the history of British Columbia and they got nowhere.

Not until the Vancouver Sun ran another front-page story, again displaying the .22’s photo. On August 7, 1965—pushing three years after Dianne and Leslie’s murders—a tipster who requested confidentiality came forward and fingered Ronald Eugene Ingram as the owner of Winchester Model 63 .22 with serial number 41649A.

Ronald Ingram was now living in North Vancouver and worked as a baker. The police learned that in October of 1962, Ingram had resided in Nanaimo along with his wife and three children where he co-owned the Parklane Bakery on Harewood Road. He moved from Nanaimo to North Vancouver shortly after the Lovers Lane murders occurred.

Ingram and his vehicle were dead ringers for the strange man who got his auto stuck on Harewood Road. The police seized his vehicle. Even though a lot of time had passed, they found dried bloodstains in it that matched Dianne Phipps’s blood type.

The police also got information that Ronald Ingram had used the now-notorious .22 to shoot rats in his bakery’s storeroom. Armed with a warrant and a chainsaw, the police recovered bullets from the storeroom wall that matched the .22’s unique firing signature and the ones that killed Dianne and Leslie.

They arrested Ronald Ingram and charged him with capital murder. To this point, no one in the legal circles ever heard of him. He had no criminal record and his name never surfaced in the intense investigation—until he was linked to the murder weapon.

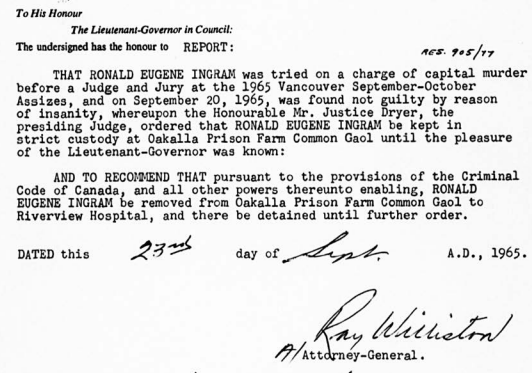

The medical and psychiatric circles had certainly heard of Ronald Ingram, though. He had a lengthy history of mental illness including having maniacal episodes. Ingram confessed to murdering Dianne Phipps and Leslie Dixon, claiming he was in a maniacal state at the time. In one of the speediest trials I’ve ever heard of, Ingram was found not guilty by reason of insanity. He was ordered locked up under the authority of Section 545 of the Canadian Criminal Code and held “until the pleasure of the Lieutenant Governor was known“.

Ronald Ingram was incarcerated at the maximum-security Forensic Psychiatric Institute at Riverview Hospital in the Greater Vancouver area. Over time, Ingram’s classification was lowered to medium-security and he was consecutively placed in a less restrictive psychiatric environments. In 1976—fourteen years after these truly horrific crimes by a homicidal maniac—Ronald Eugene Ingram simply walked out the front door of his mental hospital. He was never heard of again.

And that’s the true story Dave told me about the maniac murders at Lovers Lane.