This piece is reproduced from Ted Gioia’s Honest Broker. The Dyingwords site gives full attribution to Ted Gioa and does not benefit in any way by sharing it.

Before they executed Socrates in the year 399 BC—on charges of impiety and corrupting youth—the philosopher was given a chance to defend himself before a jury. Socrates started his defense with an unusual plea. He told his listeners that he had no skill at making speeches. He just knew the everyday language of the common people.

Before they executed Socrates in the year 399 BC—on charges of impiety and corrupting youth—the philosopher was given a chance to defend himself before a jury. Socrates started his defense with an unusual plea. He told his listeners that he had no skill at making speeches. He just knew the everyday language of the common people.

Socrates explained that he had never studied rhetoric or oratory. He feared that he would embarrass himself by speaking so plainly in his trial defense. “I show myself to be not in the least a clever speaker,” Socrates told the jurors, “Unless indeed they call him a clever speaker who speaks the truth.”

He knew that others in his situation would give “speeches finely tricked out with words and phrases.” But Socrates only knew how to use “the same words with which I have been accustomed to speak” in the marketplace of Athens.

Socrates wasn’t exaggerating. His entire reputation was built on conversation. He never wrote a book—or anything else, as far as we can tell.

Spontaneous talking was the basis of his famous “Socratic method”—a simple back-and-forth dialogue. You might say it was the podcasting of its day. He aimed to speak plainly—seeking the truth through open and unfiltered conversation.

That might get you elected President in the year 2024. But it didn’t work very well in Athens, circa 400 BC. Socrates received the death penalty—and was executed by poisoning.

Is that shocking? Not really. Western culture was built on one-way communication. Leaders and experts speak—and the rest of us listen.

Socrates was the last major thinker to rely solely on conversation. After his death, his successors wrote books and gave lectures. That’s what powerful people do. They make decisions. They give orders. They deliver speeches.

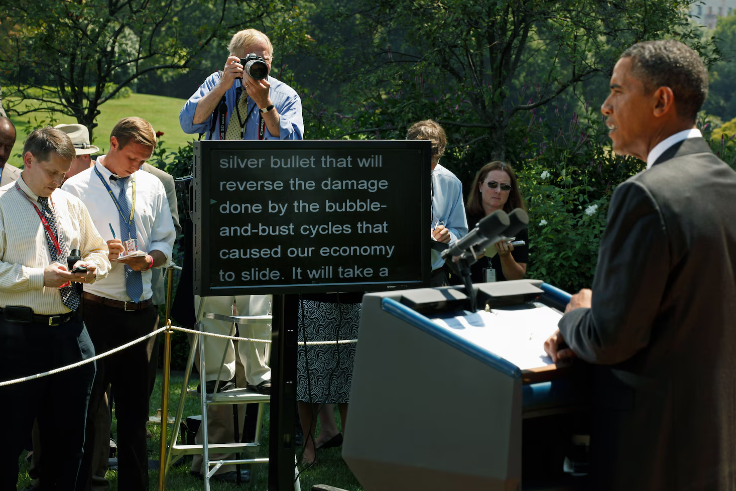

But not anymore. In the aftermath of the election, the new wisdom is that giving speeches from a teleprompter doesn’t work in today’s culture. Citizens want their leaders to sit down and talk.

And not just in politics. You may have seen the same thing in your workplace—or in classrooms and other group settings. People now resist one-way orders from the top.

The word “scripted” is now an insult. Plainspoken dialogue is considered more trustworthy. This is part of the up-versus-down revolution I’ve written about elsewhere—a conflict that, I believe, may have even more impact on society than Left-versus-Right.

For better or worse, the hierarchies we’ve inherited from the past are toppling. To some extent, they are even reversing. The era of teleprompters and talking points has come to an end.

This is now impacting how leaders are expected to speak. Events of the last few days have raised awareness of this to a new level—but the ‘experts’ should have expected it. That’s especially true because the experts will be those most impacted by this shift.

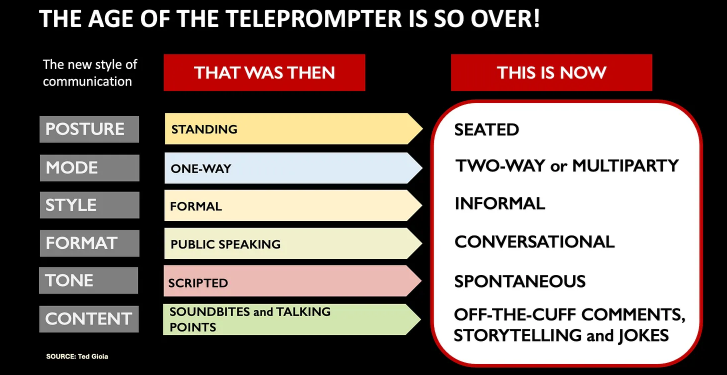

Here are the six new rules of engagement—for politicians, broadcasters, and all aspiring experts, decision-makers, and leaders.

- You gain more trust when seated, not standing.

- Don’t speak at people—speak with them.

- An informal tone is more persuasive now. Even leaders must adjust to this.

- Conversations have more influence than speeches.

- Spontaneous communications delivered from a personal standpoint are considered more ‘real’ than a script created by a team or speechwriter.

- Soundbites and talking points are less impactful than storytelling, humor, and off-the-cuff comments.

We could debate endlessly whether this is good for society. For my part, I expect both costs and benefits from this new style of communication. But the more significant fact is that this is now inevitable.

The results may be clumsy and painful to watch. Institutional media will now try to prove that it can be edgy and alternative and freewheeling. This will often look like a dinosaur pretending that it’s a ballerina.

But they have no alternative. You might as well try to rebuild the Tower of Babel from a Lego set. The old hierarchies aren’t coming back anytime soon.

Back in March, I reflected on how my writing style has become more conversational during the last three years. I tried to explain why—but it just boiled down to that fact that it felt right to adopt this conversational tone.

What I wrote back then now seems a bit prophetic of this new style of public discourse. A few months after I launched on Substack, I noticed that my sentences and paragraphs were changing. And not in a small way.

This surprised me. I had been publishing in commercial media since I was a teen, and felt I really found my stride around the time I reached my forties. Ten books written since then validated this complacent confidence by attracting enthusiastic readers.

Why would I change now? What made it more unsettling was that I didn’t understand why I was writing differently….

I only gradually figured out that I was now writing the same way I spoke in private conversation. It was almost as if I’d let my guard down, and was talking off the record, or with a close friend. I didn’t know that could be a writing style. But it felt right, so I kept doing it.

I believe that a lot of people are coming to the same realization. The world has changed, and communication styles must adapt to the new reality.

Why is this happening now?

Here’s the reality—rhetorical skills and speechmaking got degraded during the last decade. This top-down approach works best when it is rigorous, logical, and organized. But in an age of insults, taunts, and denunciations, speechifying starts to feels like browbeating—a never-ending harangue.

Too much of public discourse, in recent years, has boiled down to powerful people (sometimes of limited intellect) screaming into a microphone from a bully pulpit. That’s not what oratory should be, but it’s what it has become.

These things feed on themselves. If you grasp the dominant Girardian mimicry in society today, you shouldn’t be surprised to see that screaming from one elite eventually causes others to scream back. And the conflicts thus escalate—getting angrier and more shrill with each passing year.

Don’t tell me that you haven’t noticed. Most of us are now burned out on this kind of hot oratory—whether from friends or enemies. A conversational style feels refreshing by comparison.

Rhetoric and speechifying won’t regain their influence until they get cleaned up. We need different leaders from the current crop before that will happen. Oratory won’t come back until genuine orators emerge as leaders.

Until then, get ready for the new era of rambling conversations. Not long ago, those endless three-hour Joe Rogan podcasts seemed bizarre. Even more to the point, they ran against the conventional wisdom. The audience wanted short soundbites—the ‘experts’ all agreed on this. Nobody had time to listen to a three-hour podcast.

But now every media outlet is shifting to conversational formats. Podcasting is thriving because of this approach. Many successful YouTubers are doing the exact same thing. Writers (on Substack and elsewhere) are also embracing a more conversational tone. Leaders will now have more authority when they speak while sitting—not standing.

TV news channels have grasped this new reality. Until quite recently, broadcast journalism was built on talking heads who could read a script with confidence. Those days are over—instead of the declamatory news anchor, expect to see more spontaneous interactive formats like The View or The Five.

Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

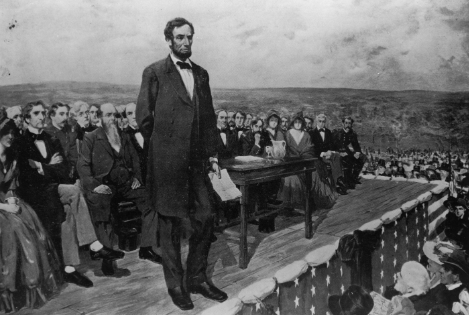

In 1921, President Warren Harding hired the first full-time presidential speechwriter. His predecessor, Woodrow Wilson was the last president who wrote his own speeches. In the aftermath, no serious candidate could afford to rely on spontaneous communicating in everyday words. A leader needed to be a powerful orator, and every word needed to be perfect.

Around that same time, the broadcasting industry was born with the rise of radio—and it followed the same rules. News reels and (later TV journalism) also adopted a polished rhetorical style.

Consider Walter Winchell—the most famous broadcaster in the United States during the 1940s. Does anybody speak in this declamatory way nowadays? It sounds grating to our ears today. It feels fake. But every broadcaster talked like this until the second half of the twentieth century.

TV softened this style—but only a tiny bit. Unscripted conversational styles got adopted in talk shows and game shows. But TV news journalists still sounded like orators delivering a carefully written speech.

Even the best of them—for example, Walter Cronkite, the most popular TV journalist of the 1960s—still sounded very staged and scripted and extremely unlike anybody having a conversation. Could you imagine Joe Rogan—or even Anderson Cooper or Oprah Winfrey—talking like this?

You can’t really do broadcasting like this anymore. Some people try—for example, NPR hosts still hold on to a variant of this scolding tone (even when conducting interviews!). But how’s that been working lately?

Yet, even back in the 1960s, if you stayed up late and watched The Tonight Show, you got introduced to an entirely different way of talking to an audience. This is the true forerunner of today’s new conversational tone.

The Walter Cronkite and Johnny Carson film clips come from the same year—and show the huge gap between professional discourse of politicians and journalists as compared with the more informal, unscripted approach of entertainers.

This gap is now disappearing in every communication forum. Social media is the most obvious place, but spontaneity is now the rule almost everywhere. The Age of the Talking Head is over.

Broadcasters will feel the pinch. But so will almost everybody else—politicians, educators, doctors, ministers, coaches, managers, and any other individual who needs to exercise leadership in any group setting whatsoever.

Many are not ready for this. Some will believe that they are immune to change and will keep bullying from the bully pulpit. Don’t be one of them—because their power and influence will erode very quickly.