On December 15, 1944, legendary big band leader and musician Glenn Miller disappeared while on a military flight from England to France. No trace of Miller or the airplane has ever been found, and he was declared dead one year later. Various theories of what occurred have been tossed around over the years. Some are pretty far out, but one conclusion is hard to argue against. Here’s the likely explanation about who really killed big band legend Glenn Miller.

On December 15, 1944, legendary big band leader and musician Glenn Miller disappeared while on a military flight from England to France. No trace of Miller or the airplane has ever been found, and he was declared dead one year later. Various theories of what occurred have been tossed around over the years. Some are pretty far out, but one conclusion is hard to argue against. Here’s the likely explanation about who really killed big band legend Glenn Miller.

Alton Glenn Miller was born on March 1, 1904, in Clarinda, Ohio. He was forty years old when he died at the height of his musical popularity. Today, his celebrity status would equal mega stars like (according to Chat GPT) Beyonce, Taylor Swift, Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, Adele, or Rihanna. News of Miller’s disappearance shook the free world, not just the music industry. He was just that popular of an entertainer.

Also, according to Chat, “It’s important to note that the entertainment landscape has evolved significantly since the 1940s, and the way celebrity status is perceived and measured has changed as well. Therefore, while these modern entertainers have achieved considerable fame and success, it’s challenging to draw a direct parallel to Glenn Miller’s celebrity status during his time.”

Miller achieved his fame in gradual steps. He wrote his first composition in 1928 while being mentored by “The King of Swing”, Benny Goodman. One-by-one, Miler released timeless tunes like In The Mood, Chattanooga Choo Choo, and Moonlight Serenade. To this day, no individual or group has recorded more Top Ten hits than the Glenn Miller Band, and his style continues to be covered by top swing, jazz, and big band artists.

Miller achieved his fame in gradual steps. He wrote his first composition in 1928 while being mentored by “The King of Swing”, Benny Goodman. One-by-one, Miler released timeless tunes like In The Mood, Chattanooga Choo Choo, and Moonlight Serenade. To this day, no individual or group has recorded more Top Ten hits than the Glenn Miller Band, and his style continues to be covered by top swing, jazz, and big band artists.

In 1942, following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor and the Americans entering the European war theatre, Miller enlisted in the U.S. Army. His talent and skill were recognized by General Eisenhower who awarded Miller the commissioned rank of Major and tasked him to develop a troop morale program. In two and a half years, Glenn Miller with his hand-picked wind band performed over 900 shows for U.S. and Allied soldiers, sailors, and airmen. They also made 500 radio broadcasts for fighters in Europe and Africa.

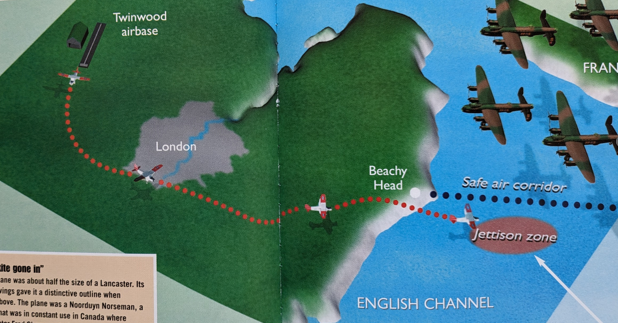

When France was liberated in late 1944 and the Nazis were on the run, the Glenn Miller Band was scheduled to perform a huge celebration concert in downtown Paris. Miller’s band and equipment were sent by sea and road from England and prepared for Miller’s personal arrival. Glenn Miller, himself, remained at Eisenhower’s Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF) near Bedford, England north of London. This was home to Eighth Army Air Force Command at the airfield known as RAF Station Twinwood Farm which held a mainly transport fleet rather than fighter and bomber squadrons.

Bad weather in France and over the English Channel delayed Miller’s departure from Twinwood on December 13 and 14, 1944. By midday on Sunday, December 15, the weather improved and Miller jumped aboard a small U.S. Amy utility airplane flown by a twenty-year-old rookie pilot named Stuart Morgan for a direct, non-stop flight from Twinwood to Paris. Also on board was Lt. Col. Norman Baessell who was friends with Glenn Miller. The three men departed at 13:55 (1:55 pm) local time and flew off towards France. They were never heard of again and the airplane has never been found, intact or wrecked.

Because this was an unscheduled service flight, Miller was not recorded to be onboard and was not noticed missing until three days later. This was partly due to Allied preoccupation with the Battle of the Bulge which started on December 16. A limited search found nothing, and it was presumed the plane dropped from the sky over the English Channel. There’s no doubt, though, that Glenn Miller was on that plane as thirteen witnesses confirmed they’d watched him leave from Twinwood.

One year after Glenn Miller was last seen alive, he was officially declared dead as per army policy. An army board of inquiry released a finding on January 20, 1945, that Miller’s flight crashed over the English Channel due to a combination of human error, mechanical failure, and bad weather. Miller, along with Baessell and Morgan, are still, to this day, listed as Missing In Action (MIA) by the U.S. Army.

Theories about what caused Glenn Miller’s disappearance began circulating shortly after the news broke to the world on December 24, 1944. The leading speculations are:

-

Miller was on a secret mission authorized by Eisenhower to negotiate peace with Hitler. Instead, the Nazis kidnapped Miller, tortured him, then killed him and disposed of the body.

-

Miller died of acute heart failure while cavorting in a Paris brothel. His death was covered up to avoid embarrassment to his wife and family.

-

The airplane froze up over the English Channel, the engine quit, and it crashed into the water.

-

The airplane was accidentally shot down by friendly fire and this was covered up.

Let’s look at these theories with objectivity and apply Occam’s Razor to the overall case—Occam’s Razor being the principle of parsimony where, when faced with multiple hypotheses, the simplest answer is usually the right answer. Especially where there’s proof to back up the conclusion.

The secret mission story is ridiculous. To think an entertainer—even one as high-profile as Glenn Miller—would sway any influence over a madman like Hitler is, well, just plain dumb.

The whorehouse story is just as ridiculous. Glenn Miller was known to be of the highest integrity. He was solidly married and had zero recorded incidents of impropriety. Besides, this theory and the Hitler one would have required an identifiable airplane that landed and was stored somewhere.

The whorehouse story is just as ridiculous. Glenn Miller was known to be of the highest integrity. He was solidly married and had zero recorded incidents of impropriety. Besides, this theory and the Hitler one would have required an identifiable airplane that landed and was stored somewhere.

Let’s examine the ice-up and crash theory. That requires reviewing what kind of airplane it was and whether freezing/mechanical failure was likely. It was not. The missing airplane was a C-64 Norseman single-engine bushplane. It was built in Canada along with 902 other Norsemans and specifically designed to fly in harsh weather and arctic temperatures. Norseman planes are still in operation today, and they’re equally as dependable to the aged DeHavilland Beavers and Otters that are virtually indestructible.

The chance that the Norseman froze its carburetor and/or wings is highly improbable. That trip was done in weather the Norseman thrived upon. As well, freezing and stalling allows considerable time for the pilot to radio a Mayday and to deadstick it down to a belly landing on the water where the occupants could take to a liferaft.

So what about the friendly fire suggestion? For one thing, all air combat was long over in the region so flack from a ship or shore battery was not realistic. Same with a fighter intercept. The flight was in full daylight and the Norseman was highly identifiable as a non-armed American service craft.

So what about the friendly fire suggestion? For one thing, all air combat was long over in the region so flack from a ship or shore battery was not realistic. Same with a fighter intercept. The flight was in full daylight and the Norseman was highly identifiable as a non-armed American service craft.

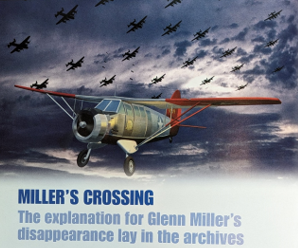

But the friendly fire theory—accidental armament engagement—has merit and meets the Occam’s test along with sufficient proof to let the theory support the balance of probabilities and solve the mystery of who really killed Glenn Miller. The answer lies with documents and testimony in the Royal Air Force archives.

In 1956, a British film titled The Glenn Miller Story aired to the public. It ended with an image of a Norseman flying off into the sky over the Channel. A man by the name of Fred Shaw saw the show and came forward with fascinating information.

Shaw had been a navigator on an RAF Lancaster bomber. On a daylight bombing to Germany, Shaw’s formation of 139 Lancasters was recalled before dropping their loads on Nazi territory. Because it’s dangerous to land a heavy bomber like a Lancaster with live ordnance onboard, it was standard operating procedure to jettison the bombs in a specific zone in the English Channel that was restricted to all other aircraft—a no-go, no-fly region ten miles west of the safe air corridor that the Norseman was flight-planned to.

Shaw claimed that he and two other crew members saw a Norseman below them when they jettisoned their bombs and watched it get hit and then spiral down to the sea. He claimed there was nothing could be done to save the Norseman occupants, so they returned to base without any official report as they had no idea as to the Norseman’s specific identity let alone occupant load or flight purpose. Shaw stated he thought nothing more of the incident until watching the biopic and then put two and two together with the date of the incident.

At first, Shaw was written off as a publicity seeker. People suggested he couldn’t positively identify the crippled plane from his vantage point. Shaw countered, stating he had a full, unobstructed view and he was very familiar with the silhouette of a Norseman as he took his navigator training in a Norseman while in Canada, logging hundreds of hours in this airplane.

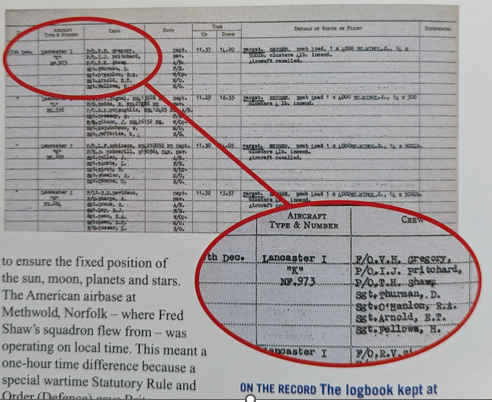

The simple, get-to-the-bottom remedy was to verify flight times. There was no question that Miller’s flight left Twinwood at 13:55 (1:55 pm) local time on December 15. The RAF logs for Shaw’s Lancaster identifier ”K” NF.973 showed it returning to base at 14:20 (2:20 pm) on December 15. Extrapolating times, this would calculate Shaw’s bomber to jettison its load at approximately 13:40 (1:40 pm) which was almost the exact time that Miller’s plane departed Twinwood airfield.

Because of the time conflict, it seemed obvious that the Norseman could not have been under the bomb-dropping Lancaster and that was that. Until 1984, when an aviation historian named Roy Nesbit, on behalf of the Air Historical Branch of the British Ministry of Defense, conducted an independent investigation, reopening the Shaw claim of the accidental bomb strike. He found the answer to the apparent time mismatch within the logbooks and route maps kept at the Public Record Office in London.

To Nesbit, who was a military pilot and very familiar with record reading, the clue was so straightforward as to be silly. The Lancasters were operating on Greenwich Meantime. They never adjusted for daylight savings time. However, due to the war, a special ordinance called the Statutory Rule and Time Order allowed Britons to operate on the one-hour earlier than Greenwich standard time. According to GMT, the Norseman actually took off at 12:55—45 minutes before the bomb jettison and exactly the time needed to fly a Norseman at 155 mph and place it under the Lancaster formation.

With the timing worked out, the question remained as to why the Norseman was out of the safe air corridor and into the extremely dangerous jettison zone. That answer lay with the pilot, Flying Officer Stuart Morgan. His service records established that he had only recently qualified on the Norseman, and he had no experience in flying with instruments in poor weather. Morgan would have been navigating solely on a magnetic compass using visual flight rules (VFR) on a cloudy day. Only a tiny misjudgment by Morgan or a fraction of a degree off course could easily have placed him ten miles to the west of his designated safe air corridor and into the danger zone.

Given that something suddenly, catastrophic, and overwhelming unsurvivable happened to the missing Norseman, the logical and simple conclusion is it probably was accidentally struck by friendly bombs jettisoned by a British Lancaster warplane. In all likelihood, the RAF really killed big band legend Glenn Miller.

Hi! New reader here and this is the first article I’ve read. I can already tell it certainly won’t be my last. Even though this happened well before I was born, I love history, mysteries, and big band. Another commenter above voiced my same thoughts about why Shaw or anyone else reported it. It was disturbing that “he thought nothing more of it.” But, your reply has put another perspective on it and you’re right…guess we had to be there. As you say, it was a different time. Thank you for an excellent read that I shared with my mother-in-law, who first told me about the Glenn Miller mystery and tragedy years ago. Have a wonderful day!

So nice to hear from you, Renee, and welcome aboard the Dyingwords train. It’s really rewarding to read comments like yours. So happy you enjoyed the piece and I’ll keep ’em coming 🙂

This tale came as a shock to me. Much as I love Big Band music as well as WWII (European theatre) history, I’ve never read anything about Miller’s demise!

My main question after reading this, though, is why has no-one gone to the coordinates of the Lancaster drop to see if there’s wreckage left to recover?

Hi Cyn! Actually there is a movement to explore the region to find the wreckage. Here’s the link: https://tighar.org/Projects/GlennMiller/glennmiller_3.html BTW, thanks for being a regular reader and commenting 🙂

Ooh! Thank you!

And, of course! Happy to support you, and love your great content, even when I don’t have time to chime in. You always have fascinating topics!

Very interesting! Thank you for doing all the research and sharing with us. My husband was equally impressed.

Thanks, Cecilia – I try to find pieces I find interesting and dig into them out of curiosity – then I write about them to make sure I understand the story – hopefully others enjoy the stuff, too. And thanks for your continual support!

Wow…how could pilots and navigators know they hit a plane and NOT report it? And then not talk about it for all those years? Thanks for your piece, Garry. Fascinating stuff!

I guess you had to be there, Carolyn. My dad was on a Lancaster crew in WW2, and I remember him saying their priority was keeping their aircraft sound and the crew safe – not worrying about collateral damage/incidents around them. There was so much going on in a bombing operation that I can see how this accidental hit was observed and not reported. Like I said, it was the times and you had to be in the mindset of just trying to stay alive yourself. Also, the crew Shaw was part of would not know if it was their bombs that downed the Norseman – it was a carpet jettison from over a hundred other planes so it could have been a hit from any of the other bombers.