The old-fashioned private detective with hardboiled ways has been around since the 1920s. He/she’s still here a hundred years later and shows no sign of going away. There are good reasons—many good reasons—for hardboiled detective fiction’s popularity, but one seems to stand above the rest. That’s escapism. You can safely escape into the fictional, fast-moving, danger-filled crime world and let your hardboiled detective kill your enemies for you.

The old-fashioned private detective with hardboiled ways has been around since the 1920s. He/she’s still here a hundred years later and shows no sign of going away. There are good reasons—many good reasons—for hardboiled detective fiction’s popularity, but one seems to stand above the rest. That’s escapism. You can safely escape into the fictional, fast-moving, danger-filled crime world and let your hardboiled detective kill your enemies for you.

This post is timely for me as a crime writer. I’ve recently taken the plunge onto the mean streets of hardboiled fiction writing after a coincidental brush with the film industry. I was going about my way putting out based-on-true-crime books in a planned 12-part series when I got an unsolicited call from a New York City film producer. It was about a historic serial murder case I’d worked on and published an article about.

Google being Google, the film producer found me and we had a nice long chat about the true crime case. He’d done his homework before our Zoom call and was somewhat familiar with my books. Being the diligent and always-on-the-look film producer that he is, he asked the 64,000-dollar question, “So what else you got going?”

What I had on the go—in the back of my mind for the last few years—was a concept for a hardboiled crime fiction series based on the 1920s style but set in the 2020s. I said, “Here’s the logline. A modern city in dystopian crisis surreptitiously enlists two private detectives from its utopian past to dispense street justice and restore social order.”

There was a long pause before he said, “Reeeeally… This is exactly what my colleague at (leading net-stream provider) is looking for. Can we set up a joint talk?”

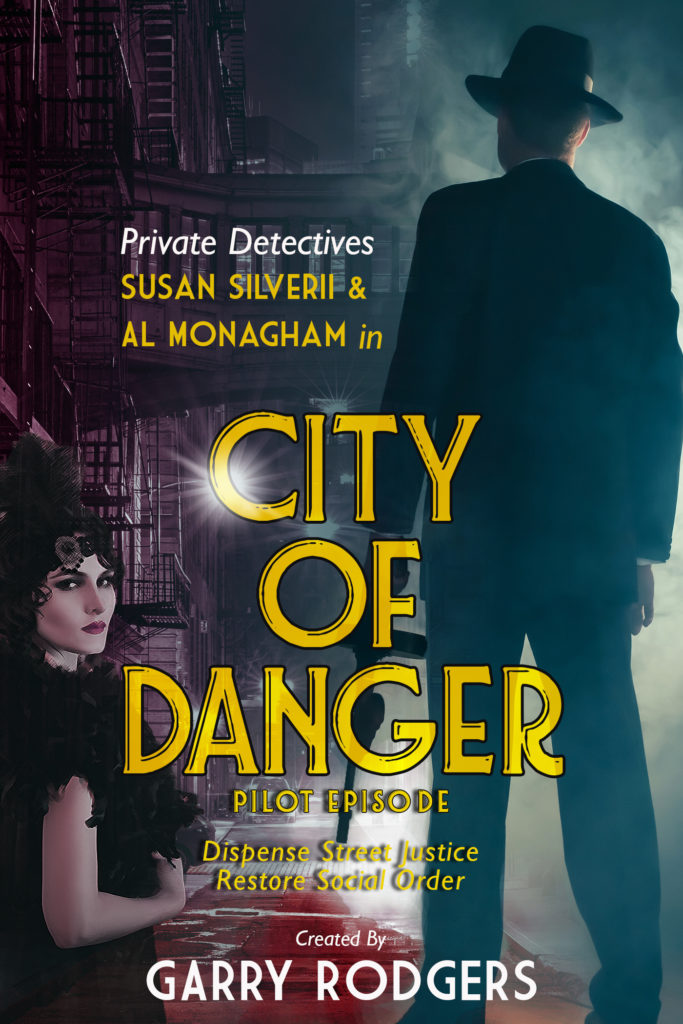

Not being one to look the proverbial gift-horse in the mouth, I readily agreed. Now, I’m on a full-time mission to figure out how to do this and get something in place by the fall. Regardless if this ever gets “Green Lit” in film, I’m retaining the ebook, print, and audio rights to the series titled City Of Danger.

I’ve researched hardboiled detective fiction for the past three months. It’s utterly consumed me, and I’m completely hooked on a fascinating genre. I’ve always believed that the best way to learn something is by writing on it or, better yet, teaching it. With that in mind, a month ago I wrote a post on The Kill Zone about hardboiled crime fiction’s popularity. Now, I’ll steal back my own work and republish the piece here on DyingWords. Here goes:

— — —

Crime doesn’t pay, so they say. Well, whoever “they” are, they aren’t in touch with today’s entertainment market because crime—true and fiction—in books, audio, television, film, or net-streaming, is a highly popular commodity. One solid crime writing sub-genre, detective fiction, is hot as a Mexican’s lunch.

Detective fiction has been hot for a long, long time. Crime writing historians give Edgar Allan Poe credit for siring the first modern detective story. Back in 1841, Poe penned Murders In The Rue Morgue (set in Paris), and it was a smash hit in Graham’s Magazine. Poe’s detective, C. Auguste Dupin, used an investigation style called “ratiocination” which means a process of exact thinking.

Poe’s style brought on the cozy mysteries, aka The Golden Era of Crime Fiction of the 1920s. Detectives like Sherlock Holmes and Miss Marple solved locked-room crimes. They intrigued readers but spared them gruesome details like extreme violence, hardcore sex, and graphic killings.

The golden crime-fiction genre evolved into the hardboiled detective fiction movement, circa 1930s-1950s. Crime writers like Dashiell Hammett gave us the Continental Op and Sam Spade. Raymond Chandler brought Philip Marlowe to life. Carroll John Daly convincingly conceived Race Williams. And Mickey Spillane, bless his multi-million-selling soul, left Mike Hammer as his legacy.

The golden crime-fiction genre evolved into the hardboiled detective fiction movement, circa 1930s-1950s. Crime writers like Dashiell Hammett gave us the Continental Op and Sam Spade. Raymond Chandler brought Philip Marlowe to life. Carroll John Daly convincingly conceived Race Williams. And Mickey Spillane, bless his multi-million-selling soul, left Mike Hammer as his legacy.

The ’60s to 2000s gave more great detective fiction stories. Anyone heard of Elmore Leonard? How about Sarah Paretsky and Sue Grafton? Or, in current times, Michael Connelly, Megan Abbott, and a wildcard in the hardboiled and noir department, Christa Faust?

These storytellers broke ground that’s still being tilled by great fictional detectives. Television gave us Perry Mason, Ironside, Columbo, Jack Friday, Kojack, and Magnum. Murder She Wrote? How cool was mystery writer and amateur detective Jessica Fletcher? And let’s not even get into big screen and the now runaway net-stream stuff.

So why the unending popularity of detective fiction? I asked myself this question to understand and appreciate the detective fiction part of the crime story genre. I worked as a real detective for decades, and I know what it’s like to stare down a barrel and scrape up a cold one. But once I reinvented myself as a crime writer, I had to learn a new trade.

I’m on an even-newer venture right now, and that’s developing a net-streaming style series. It’s a different—but not too different—delve into hardboiled detective fiction, and the series is titled City Of Danger. To write this credibly, and with honor to heritage, I’ve plunged into a rabbit hole of research that’s becoming more like a badger den or a viper pit.

What I’m doing, as we “speak”, is learning this sub-genre of crime writing—hardboiled detective fiction—and I’ve learned two things. One, I found out I knew SFA almost nothing about this fascinating fictional world that’s entertained many millions of detective fiction fans for well over a hundred years. Two, detective fiction has far from gone away.

My take? Detective fiction—hardboiled, softboiled, over-easy, scrambled, or baked in a cake—is on the rise and will continue being a huge crime-paying moneymaker in coming years. There are reasons for that, why detective fiction remains so popular, and I think I’ve found some.

My take? Detective fiction—hardboiled, softboiled, over-easy, scrambled, or baked in a cake—is on the rise and will continue being a huge crime-paying moneymaker in coming years. There are reasons for that, why detective fiction remains so popular, and I think I’ve found some.

I stumbled on an interesting article at a site called Beemgee.com. Its title Why is Crime Fiction So Popular? caught my attention, so I copied and pasted it onto a Word.doc and dissected it. Here’s the nuts, bolts, and screws of what it says.

Crime fascinates people, and detectives (for the most part) work on solving crimes. But the crime genre popularity has little to do with the crime, per se. It has far more to do with the very essence of storytelling—people are hardwired to listen to stories, especially crime stories.

Detective fiction is premiere crime storytelling and clearly exhibits one of the fundamental rules of storytelling: cause and effect. In detective fiction, every scene must be justified—each plot event must have a raison d’etre within the story because the reader perceives every scene as the potential cause of a forthcoming effect.

Picture a Roman arch bridge. Every stone is held in place by its neighbor just like story archs with properly set scenes. Take away one scene that doesn’t support the story arch and the structure fails.

Well-written detective fiction has a bridge-like structure. Each scene in the storytelling trip has some sort of a cause that creates an effect. This subliminal action keeps readers turning pages.

The article drills into detective fiction cause and effect. It rightly says the universe has a law of cause and effect but we, as humans, can’t really see it in action. But we’re programmed to know it exists, so we naturally seek an agency—the active cause of any actions we perceive.

Detective fiction stories, like most storytelling types, provide a safety mechanism. A detective story is built around solving a crime by following clues. A cause. An effect. A cause. An effect. The story goes on until you find out whodunit and a well-told story leaves you with a satisfying end where you’ve picked up a take-away safety tip.

Detective fiction stories, like most storytelling types, provide a safety mechanism. A detective story is built around solving a crime by following clues. A cause. An effect. A cause. An effect. The story goes on until you find out whodunit and a well-told story leaves you with a satisfying end where you’ve picked up a take-away safety tip.

But detective fiction stories aren’t truly about whodunit. Sure, we want the crook caught and due justice served. However, we want to know something more. We want to know motive, and this is where the best detective fiction stories shine. They’re whydunnits.

Whydunnits are irresistible stories. They’re the search for truth, and in searching for truth in detective fiction storytelling—why this crime writing sub-genre remains so popular—I found another online article. Its title Why Is Detective Fiction So Popular? also caught my attention.

This short piece is on a blog by Swiss crime writer, Cristelle Comby. If you haven’t heard of Cristelle, I recommend you check her out. Her post has a quote that sums up why detective fiction is so popular, and it’s far more eloquent than anything I can write. Here’s a snippet:

“Detective novels do not demand emotional or intellectual involvement; they do not arouse one’s political opinions or exhaust one by its philosophical queries which may lead the reader towards self-analysis and exploration. They, at best, require a sense of vicarious participation and this is easy to give. Most readers identify themselves with the hero and share his adventures and sense of discovery.

The concept of a hero in a detective story is different from that of a hero in any other kind of fictional work. A hero in a novel is the protagonist; things happen to him. His character grows or develops and it is his relationship to others which is important. In a detective story, there is no place for a hero of this kind. The person who is important is the detective and it is the way he fits the pieces of the puzzle together which arouses interest. Thus in a detective story it is the narration and the events which are overwhelmingly important, the growth of character is immaterial. What the detective story has to offer is suspense. It satisfies the most primitive element responsible for the development of story-telling, the element of curiosity, the desire to know why and how.

Detective stories offer suspense, a sense of vicarious satisfaction, and they also offer escape from the fears and worries and the stress and strain of everyday life. Many people who would rather stay away from intellectually ‘heavy’ books find it hard to resist these. Detective fiction is so popular because the story moves with speed.”

As a former detective, and now someone who writes this stuff, I think detective fiction is so popular because you can safely escape into a dark & dangerous world of wild causes and wild effects—full of fast-reading suspense—and you get powerful insight into what makes other people (like good guys and bad girls) tick. Yes, escapism. You can safely escape into the fictional, danger-filled crime world and let your hardboiled detective kill your enemies for you.

So that’s what went up on The Kill Zone blog. Now for a little bonus here at DyingWords. Here’s the City Of Danger series product description:

The City Of Danger is in peril. It’s in 2020s dystopian crisis with infrastructure crumbling, social systems collapsing, corruption infesting all civic layers, and crime overflowing from clogged gutters of every alley—gushing gangland and political blood onto its streets. The City Of Danger urgently needs help it can’t get from its mainstream. For salvation, it surreptitiously enlists two private detectives from its 1920s utopian past.

Susan Silverii and Al Monagham share a split-room office with frosted glass doors in the city’s low rent district. They’re ex-police officers who weren’t a good fit. It’s the Roaring Twenties, and they’ve struck out on their own. Al with his street justice vengeance. Susan with her social change agenda.

And they have a past, Susan and Al. A past of personal passion and poisoned positions. But when the City of Danger assigns, they put professionalism first and inter-conflict second as Susan Silverii and Al Monagham step from runnin’-wild, Charleston-dance speakeasies onto the mean streets in the ugly world of a modern city—an interconnected city sick with immoral chaos.

Dispense street justice. Restore social order. Treacherous tasks ordered by a desperate client— the City Of Danger.

Now for a double DyingWords bonus: Here’s a sneak peek at Scene One in the City Of Danger Pilot Episode:

CITY OF DANGER

Pilot Episode

Scene One

Monday, October 31 - 7:50 a.m.

Setting:

Noir. Bleak. Dense urban. Icy drizzle has stopped. Civic lights are still on — what still work. Hard gusts blow wet leaves that stick to cracked brick, condemned structural glass, and corroded staircase metals. A failing foghorn on the waterfront echoes off battered buildings smothered by smog — its rhythm competes with sirens screeching hopelessly towards smoke, sickness, and sadness in the slums. Closing in — methane eerily seeps from open sewer grates. It nauseates. Yet, the taste is somehow sickly sweet — almost tolerable — and now expected; unapologetically not urbane, unlike those who fight entropy’s ultimatum in the City Of Danger.

Fade In:

Camera view:

Germanic Expressionist style. High-angle, downward capture. Sharp and dull shadows through contrasted lighting. Follows six feet back on quarter-rear sides as well as directly behind.

Narrator:

The City

Voice In:

A 2021 Beamer X3 SUV, deep-sea metallic blue, brakes to a halt behind a solid-black Tesla on Mean Street, a pock-marked route with water-filled potholes in the low rent district. A stunningly attractive and stylish high-status lady — exceptionally fit — a natural brunette, except for dyed umber highlights, showing dolphin-smooth skin — in her fifties with impeccable dark brows accenting mahogany eyes and classic red wine lipstick, steps out. Her Lululemon-clad legs hit hard on crumbling asphalt. Immediately, she clicks her fob and locks her doors then rapidly scans the streetscape. Her right hand subconsciously checks her shoulder-holstered .32 auto cloaked by her unzipped yellow & black Arc’teryx rain jacket, and she hurtfully limps into the claustrophobic narrows of Peril Alley.

On the lady’s left, angle-parked with one rear door propped open and its running engine spewing propane fumes, is a mid-2000s FedEx panel van parked beside a gold-trimmed 1999 Caddy Eldorado. A greaseball Latino takes a brown paper bag from the black F/X operator who glances at the lady with his one good eye. Twice and once more.

Further, on her right, the lady’s right, is an ‘85 Chevy Impala, a boring beige four-door with a flat front tire. A prune — a sun-wrinkled old olive-skinned guy with a faded white Masters golf cap and perpetually-down fly has it jacked-up. He curses the C-Word.

The lady pauses. She frowns. In Italian, she says, “Tua madre non ti ha insegnato le buone maniere”. He replies, “Ciao bella!” She blows a kiss at the ground, flips him the bird, and falters on. She quick-lefts a shoulder check then watches straight ahead, closing at the back end of a 1976 F150 Styleside, red and silver with a lichen-spattered canopy. A loosely attached, non-local plate catches her eye. Looks abandoned, she thinks. It’s at a chokepoint in the center of tightening Peril Alley. She stops. Slightly backs up. Sniffs. Nitrogen fertilizer with trigger device? No. Probably just organic sludge in the box of a stolen pickup dumped here as usual.

The lady squeezes past the Ford’s passenger side, avoiding its dented, dirt-dripping door and smashed mirror. She looks to her left at a late-60s muscle car, a puke-green Goat — a Pontiac GTO, idling with a leaded gas, throaty rumble. She can’t see the driver, but the Goat’s passenger is a mousey-haired hippy chick giving her a suggestive smile through a part-open window. The stink of shit-grade Sinsemilla scrunches the lady’s ideal nose.

Her right hand raises. Fingers pinch, then release, and her nostrils reopen after she’s passed — cautiously favoring her left side’s now-permanent short-step.

She hesitates. Stops. She looks up.

Chuck Berry’s hit Maybellene blasts from a transistor radio on a shaky fire escape landing. It’s thirty feet above her uncovered head, the same place invasive carrier pigeons roost and fecal-drop and terminally-diseased rats cunningly climb cone-shielded steel poles to steal mildewed barley seed scattered onto delaminating plywood.

The lady shivers. She keeps on.

On her right is an alley business, a family business she knows well, a WW2 era Chinese clothes cleaner and money launderer — Ho Lim’s — tucked into the set-back alcove of a used-brick façade with cast iron plumbing barely hanging from bolts set into breaking gray mortar. The lady moves to her left, avoiding intermittent blasts of perc solvent.

Peril Alley darkens. It cools even more. The buildings grow as she approaches dead end. Twenty stories and more overshadow brownstones and brownstones overshadow antiquated infrastructure of overloaded, overheated, overhead power poles draped with time-twisted lines strung through opaque glass insulators screwed into tired wood crossbars. On the ground — unpredictable ground — foundry-built catch basins guard root-filled, tiled storm drains that swirl-down rancid water mixed with more of the city’s rottenness.

Bang!

She spins left towards the sound. Lowers and goes sideways. Minimizes her silhouette exactly as she’s been tactically trained — intensely immersed during her now-discharged service — and hooks-out her handgun. But it’s the backfire from a red-as-raw-meat ’41 Packard 180 with a badly-floated carb. The owner, a flat-capper in elbow-patched tweed, laughs. She doesn’t. She reholsters. But leaves off her safety.

A bum, a Depression-era hobo with nothing more to her miserable life than a broken broom handle with a half-tied-on, once-gray pillowcase, rummages through an unlidded dumpster with her grease-crusted hands. The hag begs. The lady responds. She opens her overcoat, removes the Calabrian leather wallet handed down through her ‘Ndrangheta family, opens it, and gives the other a five.

Ahead — just before Peril’s dead-end — phonograph sounds of Charleston dance sing-out from inside a welded steel gate guarding a Prohibition speakeasy. It’s trailing off from last night’s steamy start, raucous non-stop laughter, and this morning’s explosive finish. The lady looks right. She smiles, slightly, at the flickering on-and-off red and orange and green and blue neon sign: Topper’s Grill & Bar.

The lady stands where she can go no more down Peril Alley. There’s a large door framed into a soot-stained, rough stucco wall Tommygunned with .45 holes. It’s flanked by a now-glassless window boarded-up after the latest kerosene-wicked, flame-thrown cocktail. The door is a heavy, metal-strapped oak door — not altruistic like her eyes and her soul — more fatalistic as a mix of splintered hardwood and oozing rust. Like her, risking to be shot once again.

Beside the door are two signs, business signs, in black & white Roaring Twenties font. One’s above the other. Al Monagham Private Detective Agency is on top. The other, below, is Susan Silverii Private Detective Agency.

The lady fishes a skeleton key from her outer garment — it’s now changed from her unzipped yellow & black Arc’teryx rain jacket to a peach Flapper coat (virgin wool, of course, and a color perfectly coordinating her stunningly attractive and stylish high-status Flapper headdress). She inserts the key with her right hand — her left hand and forearm so severely injured — they’re nearly impotent — and releases the lock.

She opens the door, and Susan Silverii struggles her step into temporary safety within her shared office workspace.

Fade Out.

I’m a lurker on your blog but I love your books and I loved this excerpt. Congratulations on this new venture! I can’t wait to watch it.

Hi Laurie! So nice to hear from you… and that you’ve stopped lurking 🙂 You piqued my curiosity, so I clicked to your website – https://lauriewoodauthor.com/ – and I see you’re a Munie writing Mountie 🙂 (Only those in the Canadian LE biz will get this). Central Canada, you live? I grew up in Manitoba’s Whiteshell Park – by the Ontario border. You?

Kudos to you, Gary, for venturing – yet again – into a new genre and a (hopefully!) new career!

Here’s to your success🥂

Kate (in Ireland)

P.S. I’m available to be cast as Susan, the “stunningly attractive and stylish high-status lady” if you’d like to fly me back to Canada! 😺

Thanks so much, Kate! This is a different ride for me – I have a lot of work ahead but it’s thoroughly enjoyable. I’ll ask the real Susan if she wants to give up the limelight 😉

PS – I have Irish roots. My paternal grandfather, John Rodgers, was born in Ballymena.

Garry, I LOVE this. Brilliant concept, smart title, great set up, perfect ambience, astute timing. Good luck & do keep us informed.

Well thank you so much for your encouraging words, Ruth. My gut tells me there’s significant potential here. I’m watching the resurgent of the Golden Age cozies, and I gotta think the wave of new hardboiled is right behind. What’s old is new again, right? The film reps are enthusiastic, so that’s a good sign. As the net guy said, “This is a different take on proven material and that’s what we want. Just don’t make it too different.” I got his message 🙂

This line of Combly’s quote puzzles me: Thus in a detective story it is the narration and the events which are overwhelmingly important, the growth of character is immaterial.

Sorry, but I don’t buy that at all. Character growth is always important, regardless of genre or sub-genre. It doesn’t have to be major growth in each novel, but all characters should evolve over time. My 2c. 🙂

Your two cents are always appreciated, Sue. I’d like it more if it was a couple hundred bucks, but I’ll take what I can get. I think what she’s saying refers to classic, standalone, short word-count, hardboiled detective fiction novels (pulp) where the crime situation was the story and main character was an unchanging hard-ass like the Continental Op, Sam Spade, Mike Hammer, and guys like that. Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe character had more of a soft side but, from what I’ve read of him so far, there wasn’t much character arc as his stories evolved.

The piece I’m doing has significant character development and change planned. That’s what the series core is – how the two private detectives (main characters) evolve with progressive crimes and social change events (vis a vis 1920s – 2020s.) It’s like Joseph Wambough says, “The best stories aren’t about cops work on cases – they’re about how cases work on cops.” Happy fourth for tomorrow, my stars & stripes friend!

Exactly! Love the Wambough quote. And…really enjoyed your excerpt, too. You’ve got this! 😁