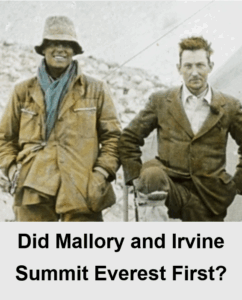

I t’s the greatest mystery in mountaineering history. And it’s a question lingering at the top of the world for over a century. Did British climbers George Leigh Mallory and Andrew “Sandy” Irvine reach the summit of Mount Everest in 1924—nearly three decades before Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay etched their names into eternity?

t’s the greatest mystery in mountaineering history. And it’s a question lingering at the top of the world for over a century. Did British climbers George Leigh Mallory and Andrew “Sandy” Irvine reach the summit of Mount Everest in 1924—nearly three decades before Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay etched their names into eternity?

The facts are buried under heavy snow, crushing ice, and glacial time. But clues remain. Some were frozen in place. Others may be waiting to thaw.

Let’s explore a deep dive (or a high climb) into one of the world’s most enduring mysteries. The answer may hinge on a single object—a missing object from the Mallory/Irvine climb that could forever rewrite mountaineering record books.

Mount Everest stands as the highest point on Earth—8,848 meters or 29,031 feet above mean sea level. It lies in the Mahalangur Himal sub-range of the Himalayas, straddling the border between Nepal and the Tibet Autonomous Region of China. The summit is known locally as “Chomolungma” or Goddess Mother of the World. Mountaineers call it the “Roof of the World”.

Climbing Everest is no walk in the park with your Birkenstocks and Bernese. Even today, with satellite weather tracking, advanced oxygen systems, carbon-fiber gear, and legions of seasoned Sherpas, it remains a deadly endeavor.

A combination of extreme cold, hurricane-force winds, avalanches, and altitude sickness kills super-fit climbers every year. Not to mention gravity. Over 300 people have perished trying to reach—or descend from—the top of the world.

Most Everest deaths are from falls, hypothermia, or high-altitude pulmonary/cerebral edema. Almost always, thse occur in the oxygen-poor “Death Zone” above 8,000 meters (26,250 feet). And even in our hyper-connected modern world, there are (and will continue to be) bodies up there that’ll never be recovered.

So, imagine attempting the climb in 1924—with wool garments, primitive crampons, hemp ropes, and homemade oxygen systems—on a route no one had ever successfully taken or surveyed before. That’s what George Mallory and Sandy Irvine set out to do.

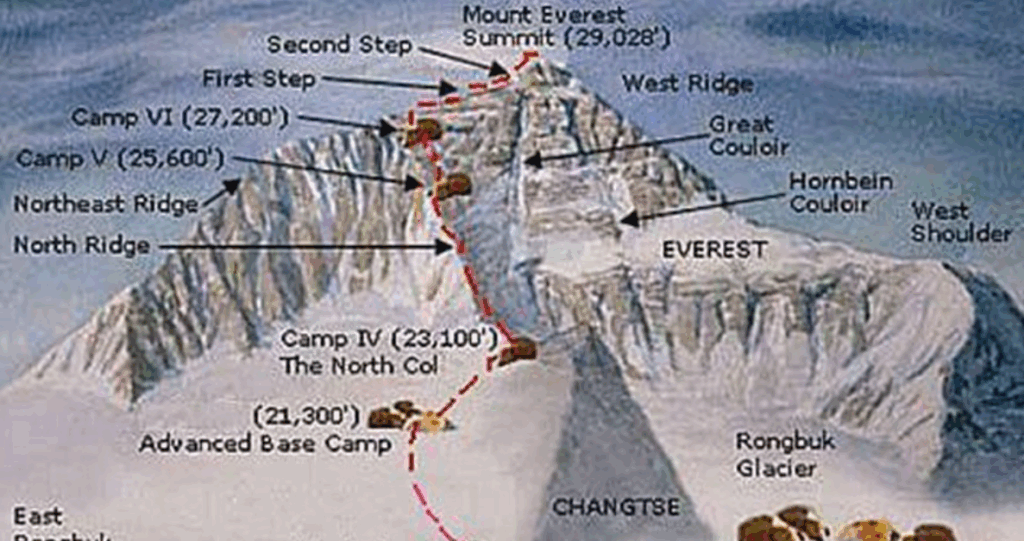

The 1924 British Everest Expedition was not the first attempt to climb the world’s highest peak. It followed two earlier British expeditions in 1921 and 1922, both of which helped map the terrain and gauge potential paths.

The 1924 team was well-organized and determined. It included experienced climbers like Edward Norton, Howard Somervell, and Noel Odell, along with George Mallory—a seasoned alpinist who had been on both previous expeditions. Sandy Irvine, only 22, was a gifted engineer brought on for his mechanical expertise with oxygen systems.

They chose to climb from the north, through Tibet, as Nepal was closed to foreigners at the time. This North Col–Northeast Ridge route remains notoriously difficult due to exposure, technical ridges, and shifting snow conditions—especially near the infamous Second Step, a 30-meter (90 foot) vertical rock face at 8,610 meters (28, 234 feet).

Despite bad weather and delays, the team pushed upward. Norton made a valiant solo attempt without supplemental oxygen and reached an astonishing 8,572 meters (28, 130 feet)—a record at the time. But the Second Step and the summit still loomed as virgins above.

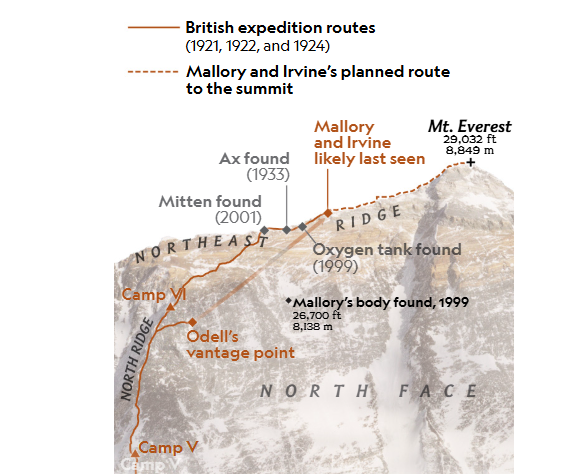

Then on June 8, 1924, Mallory and Irvine made their bid. They were last seen through a telescope by Noel Odell at 12:50 pm, appearing as “small black spots” ascending a prominent ridge—possibly the Second Step.

And then they vanished.

Let’s pause for a moment. This wasn’t just a routine summit attempt. Mallory had already become a dashing British national figure, famously answering the question of why he wanted to climb Everest with, “Because it’s there.”

And Irvine was the brilliant young newcomer, barely out of Oxford, taking on the world’s greatest challenge. They were heroes before they left base camp. And when they didn’t return, they became legends.

For 75 years, their fate remained unknown. No doubt they’d died. But had they reached the peak of Mount Everest?

In 1999, a discovery changed everything. An expedition sponsored by NOVA and the Mallory and Irvine Research Expedition, led by American climber Conrad Anker, found Mallory’s mummified body on the north face 693 meters (2271 feet) below the summit.

George Mallory was completely intact, face down, arms outstretched, showing severe head and bodily injuries consistent with a fall. His forehead was puncture with a golf ball-sized defect. His right leg was snapped. A rope and its compression injury mark curtailed his waist, suggesting the two were tethered together when one—possibly Irvine—fell and pulled the other down.

Mallory’s clothing, pack, and provisions were still with him. His stitched-leather, cobnailed boots were as perfect as the day he laced them. His pack, being as light as necessary to be for this stage of the climb, was consistent with a man who was descending. His tinted goggles were in a pouch, indicating a low light timeframe. His oxygen tanks had been shed…

In the fall of 2024, a National Geographic expedition led by Jimmy Chin uncovered partial remains believed to be those of Andrew “Sandy” Irvine. A boot, a sock labeled “A. C. Irvine,” and a foot were emerging from the ice of the Central Rongbuk Glacier, along the northern slope of Everest. These are now confirmed as Irvine’s through familial DNA testing.

Irvine’s discovery site is lower than where Mallory’s body was located in 1999. Mallory was at 8,155 meters (26,760 feet) on the north face. The exact altitude for Irvine’s lower extremety remains has not been publicly specified to avoid Everest souvenier hunters, but reports say they were “at least 700 feet lower” than Mallory’s position.

Put in perspective—Everest’s summit is 8,848 meters (29,031feet). Mallory’s body was 693 meters (2,271 feet) below the summit’s elevation. The Second Step, a 30 meter (98 foot) vertical wall is at 8,610 meters (28,250 feet) so both Mallory and Irvine apparently succumbed at least 693 meters (2,271 feet) below the summit and 455 meters (1490 feet) below the Second Step.

At least that’s what the come-to-rest remains say.

The question is, “How high did the men actually climb?” That can’t be answered by how far they fell. They could have fallen before reaching the formidable Second Step. They could have fallen when ascending the Second Step. They could have fallen right from the summit iself. Or, they could have fallen descending the Second Step returning from the summit.

The camera the pair was known to carry hasn’t ben found. Neither has Irvine’s main remains with his pack and effects, unlike Mallory. No summit photo. No turn back photo. And perhaps most curiously, a photograph of George Mallory’s wife, Ruth—one he promised to place on the summit—was missing from Mallory’s otherwise intact belongings.

That detail haunts Everest historians to this day. The Vest Pocket Kodak camera, which probably Irvine was carrying, has never surfaced. If it still exists—and if the film somehow survived—the truth may still be frozen in time.

Now, let’s revisit the 1953 summit—the one that history officially credits as the first success. On May 29, Sir Edmund Hillary of New Zealand and Tenzing Norgay, a Sherpa of Nepal, definitely reached the summit of Mount Everest via the South Col–Southeast Ridge route from the Nepalese side.

The world celebrated. Unlike Mallory and Irvine, Hillary and Norgay had advantages:

- A well-established route with prior reconnaissance

- Modern climbing gear

- Stronger oxygen systems

- Superior logistics and base support

- Detailed weather forecasts

And perhaps most importantly—they had the accumulated knowledge and failures of those who had come before. Their success was built on decades of attempts—including those of Mallory and Irvine. Without the early expeditions, there might have been no Hillary and Norgay.

Returning to the 1924 expedition’s final puzzle pieces. One of the most critical figures is Howard Somervell, who tracked weather patterns during the climb. His journals and barometric data suggest that Mallory and Irvine may have been caught in a brief but brutal storm late on June 8.

If true, that storm could have pushed them back—or killed them outright by blowing them off the mountain.

But the timing of the storm, compared with Odell’s sighting and their likely progress, still leaves open the possibility that Mallory and Irvine reached the summit before the weather closed in. Remember, they were last seen moving strongly upwards at 12:50 pm. Experts estimate they may have had another 3–5 hours of climbing ahead of them, depending on their pace, oxygen levels, weather, and terrain.

Could they have done it? Did Mallory and Invine reach Everest’s summit first?

Some argue yes. Others say no. The Second Step, now surmounted with a fixed ladder, would have been a serious obstacle in 1924. Maybe impossible given the equipment, or lack of equipment, they had.

Reinhold Messner, who is a prominent world mountaineer having solo climbed Everest without oxygen, once attempted the Second Step without a ladder. Messner remarked, “The Second Step is the key to the whole mystery. Free climbing it at this altitude, with that equipment… I have my doubts.”

But Mallory was a bold, skilled climber. And there’s that missing photo of Mallory’s wife. Why would it not be on his body when everything else was intact—unless he’d already left it on the summit?

So… did they make it? Were George Mallory and Sandy Irvine the first to crown Mount Everest? Let’s weigh the evidence.

The Case For a Successful Summit

- Odell’s sighting places them high on the ridge at a good time of day.

- They had functioning oxygen and decent weather early on.

- Mallory’s missing photo of his wife may suggest he left it at the top.

- Their drive, fitness, and skill were extraordinary for their time.

The Case Against

- The Second Step was thought unclimbable without modern gear.

- No physical proof—summit photo, journal entry, or reliable witness.

- Weather may have turned faster than Somervell recorded.

- The remainder of Irvine’s body and the camera are still missing.

Will we ever know?

That depends on whether the camera is found—and whether its film survived. Kodak experts have said that the cold may have preserved the negatives. But time and entropy are not on our side.

The harsh Everest climate, political restrictions on access, and the dangers of high-altitude recovery missions make future searches uncertain. Still, modern expeditions have better tools—LIDAR, drones, satellite imagery, and sophisticated weather modeling. And the fascination with Mallory and Irvine hasn’t faded. Their story still inspires climbers, historians, and truth-seekers alike.

My Take?

George Mallory and Andrew Irvine didn’t die in vain. Whether or not they summitted, these two pushed the edge of human potential. They risked everything to reach a place no one had ever been. And to boldly go where humans were destined to go.

In doing so, Mallory and Irvine became eternal figures in the Everest portfolio. Not just for what they did, but for what we still wonder about—why men climb mountains.

As for that summit… on the balance of probabilities… I think they might have made it… probably not… then again maybe… um, nah. But until that little Kodak camera is found, and the film is developed, Everest keeps its secret.

And maybe that’s the way mountain climbing is supposed to be.