“The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator® (MBTI®) is the best known and most trusted personality assessment in the world. It’s helped develop effective work teams, build stronger families, and create successful careers. The MBTI assessment improves quality of life for you and your organization. Giving you this personalized way to take the assessment fulfills our mission: bringing lives ‘closer to our heart’s desire’.”

“The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator® (MBTI®) is the best known and most trusted personality assessment in the world. It’s helped develop effective work teams, build stronger families, and create successful careers. The MBTI assessment improves quality of life for you and your organization. Giving you this personalized way to take the assessment fulfills our mission: bringing lives ‘closer to our heart’s desire’.”

This descriptor is from the home page of the Myers-Briggs Foundation—an organization that furthers the 1940’s work of psychologists Katharine Briggs and her daughter, Isabel Briggs-Myers, who furthered Carl Jung’s theory. They categorized people into four principal psychological functions by which humans experience the world—sensation, intuition, feeling, and thinking—and that one of these four functions is dominant for a person most of the time.

Sounds familiar… I took this personality test a few years ago and jotted the score in my notebook. Hmmm… might make a good blog topic so I’ll take it again and compare to the old score… lemme take another look at what this thing’s all about.

Myers & Briggs developed an “introspective, self-report questionnaire designed to indicate psychological preferences and typing how people perceive the world and make decisions”.

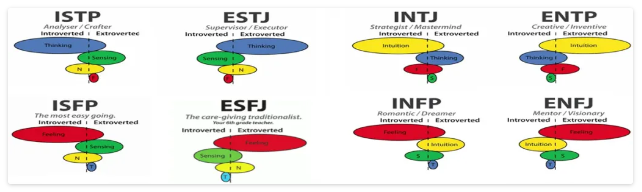

Paraphrasing from Wikepedia (this is not-so-exciting stuff—promise it’ll get livelier), “Carl Jung’s typology theories postulated a sequence of 4 cognitive functions (thinking, feeling, sensation, and intuition), each having 1 of 2 polar orientations (extraversion or introversion), giving a total of 8 dominant functions. The purpose of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator personality inventory is to make the theory of psychological types described by Jung understandable and useful in people’s lives.” I hope so because this is a pretty wordy explanation.

The theory’s essence is that seemingly random variation in behaviors is actually quite orderly and consistent, due to basic differences in the ways individuals use their perception and judgment.

Wiki goes on “Perception involves ways of becoming aware of things, people, happenings, or ideas. Judgment involves ways of coming to conclusions about what’s been perceived. If people differ systematically in what they perceive, and in how they reach conclusions, then it is only reasonable for them to differ correspondingly in their interests, reactions, values, motivations, and skills.”

Wiki goes on “Perception involves ways of becoming aware of things, people, happenings, or ideas. Judgment involves ways of coming to conclusions about what’s been perceived. If people differ systematically in what they perceive, and in how they reach conclusions, then it is only reasonable for them to differ correspondingly in their interests, reactions, values, motivations, and skills.”

Okay. Starting to make sense to me. Tell me more about these 8 functions.

“In developing the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, the aim was to make the insights of type theory accessible to individuals and groups. They addressed 2 related goals in the developments and application of the MBTI instrument:

- The identification of basic preferences of each of the 4 dichotomies specified or implicit in Jung’s theory.

- The identification and description of the 16 distinctive personality types that result from the interactions among the preferences.”

Whoa. 16? Thought there was 8? Not following the math.

“Stick with us,” they said. “We evolved — 4X4=16.”

Huh?

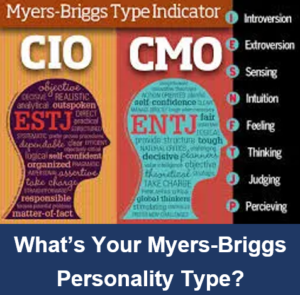

“We took Jung’s base and turned it into 4 questions:

- What’s your favorite world? — Do you prefer to focus on the outer world, or on your own inner world? This is called Extraversion (E) or Introversion (I).

- How do you absorb information? — Do you prefer to focus on the basic information you take in, or do you prefer to interpret and add meaning? This is called Sensing (S) or Intuition (N).

- How do you make decisions? — When making decisions, do you prefer to first look at logic and consistency, or first look at the people and special circumstances? This is called Thinking (T) or Feeling (F).

- How do you structure? — In dealing with the outside world, do you prefer to get things decided, or do you prefer to stay open to new information and options? This is called Judging (J) or Perceiving (P).

When you decide on your preference in each category, you have your own personality type, which is expressed as a 4-letter code. The 16 personality types of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator instrument are listed here as they are often shown in what is called a “type table”. Casually, they’re grouped into 4 personalities:

Analysts

INTJ — Architect — Imaginative & strategic thinkers with a plan for everything.

INTP — Logician — Innovative inventors with an unquenchable thirst for knowledge.

ENTJ — Commander — Bold, imaginative, and strong-willed leaders who will find or make a way.

ENTP — Debater — Smart and curious thinkers who cannot resist an intellectual challenge.

Diplomats

INFJ — Advocates — Quiet and mystical, yet very inspiring and tireless idealists.

INFP — Mediator — Poetic, kind, and altruistic, always eager to help a good cause.

ENFJ — Protagonist — Charismatic and inspiring leaders who are able to mesmerize followers.

ENFP — Campaigner — Eager, creative, and socially free-spirits who always find a way to smile.

Sentinals

ISTJ — Logicistian — Practical and fact minded individuals who’s integrity cannot be doubted.

ISFJ — Defender — Very dedicated and warm protectors, always ready to protect loved ones.

ESTJ — Executive — Excellent administrators, unsurpassed at managing things and people.

ESFJ — Consul — Extraordinarily caring, social and popular people, always ready to help.

Explorers

ISTP — Virtuoso — Bold and masterful experimenters, handy with all kinds of tools.

ISFP — Adventurer — Flexible and charming artists, always wanting to explore or experience something new.

ESTP — Entrepreneur — Smart, energetic, and highly perceptive people who truly enjoy living on the edge.

ESFP — Entertainer — Spontaneous, enthusiastic, and energetic people; life is never boring around them.

Interesting, I thought. I’ll take the test again and show DyingWords followers what makes me tick. So, I googled around and found 3 different FREE approaches to the M-B test. I took them all:

- Humanetrics — http://www.humanmetrics.com/cgi-win/jtypes2.asp

- My Personality Test — http://www.my-personality-test.com/personality-type/?gclid=CM2N_4CetsgCFQhsfgodXiEGjw

- Truity Type Finder — http://www.truity.com/test/type-finder-research-edition

I also checked the Myers-Briggs site at http://www.myersbriggs.org/ but they want $150 to sign-in, although it comes with an hour of shrink time if anyone’s interested.

So, how’d I make out?

INTJ — Every frikkin’ time, including the one I did a few years ago.

How accurate is it? You be the judge. Here’s my INTJ psychological diagnosis from the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator:

The INTJ personality type is the Introverted Intuition with Extraverted Thinking type. Individuals that exhibit the INTJ personality type are knowledgeable, inventive, and theoretical, whether they’re working on long-term personal goals or creative projects in their professions. They are “big-picture” thinkers, creating constructive ambitions and planning for them accordingly. Myers-Briggs test INTJ types hold a clear idea of what they would like to accomplish in their future, and they use that vision as motivation to complete all of the necessary steps to obtain their dreams. This dedication to their visions and their ability to find ways to achieve them make INTJ types high-functioning employees:

The INTJ personality type is the Introverted Intuition with Extraverted Thinking type. Individuals that exhibit the INTJ personality type are knowledgeable, inventive, and theoretical, whether they’re working on long-term personal goals or creative projects in their professions. They are “big-picture” thinkers, creating constructive ambitions and planning for them accordingly. Myers-Briggs test INTJ types hold a clear idea of what they would like to accomplish in their future, and they use that vision as motivation to complete all of the necessary steps to obtain their dreams. This dedication to their visions and their ability to find ways to achieve them make INTJ types high-functioning employees:

- Their looking-towards-the-future mentality helps them to create original and inspiring ideas for companies, as well as a well-thought-out plans for achieving these goals.

- Value the intellectual ability of themselves and those of others, and place a high importance on it.

- Can be adamant and commanding when the professional environment requires a certain level of authority.

- Because of their ability to think long-term, they are often placed in (or place themselves in) authoritative positions in business and groups.

- Quick to find solutions to challenges, whether that requires basing their solutions on pre-conceived knowledge or finding new information to base their decisions off of.

- Can relate newly gathered information to the bigger picture.

- Enjoy complicated problems, utilizing both book and street smarts (logical and hypothetical ideas) to find solutions.

They’re Strong Planners With Great Follow-Through

INTJ personality types are long-term goal-setters, creating plans to bring their goals to completion, and then following this plan using thought-out approaches and procedures devised by the INTJ. They are self-reliant, individualistic, and self-secure. INTJ personality types have a large amount of faith in their own competence and intelligence, even if others openly disagree or the opposite proves true. This also makes Myers-Briggs Type Indicator-assessed INTJ types their own worst critics, as they hold themselves to the highest standards. They dislike turbulence, perplexity, clutter, and when others waste their time and/or energy on something unimportant. This MBTI type is also succinct, analytical, discerning, and definitive.

In their personal lives, Myers-Briggs test INTJ types exhibit many of the same behaviors that they do in their professional lives. They expect competence from their peers and are more than willing to share their intelligence or ideas with those around them. Occasionally, INTJ personality types may find it difficult to hold their own in social situations, whether that is due to their actions or their opinions. To others, MBTI Assessment Test -assessed INTJ types seem set in their ways or opinions because of their high respect for themselves, but oftentimes reality is just the opposite, with the INTJ type taking in new tidbits of information at all times, evaluating their own opinions and ideas accordingly. They are also often seen as a tad distant, closed off from others emotionally but not intellectually.

In their personal lives, Myers-Briggs test INTJ types exhibit many of the same behaviors that they do in their professional lives. They expect competence from their peers and are more than willing to share their intelligence or ideas with those around them. Occasionally, INTJ personality types may find it difficult to hold their own in social situations, whether that is due to their actions or their opinions. To others, MBTI Assessment Test -assessed INTJ types seem set in their ways or opinions because of their high respect for themselves, but oftentimes reality is just the opposite, with the INTJ type taking in new tidbits of information at all times, evaluating their own opinions and ideas accordingly. They are also often seen as a tad distant, closed off from others emotionally but not intellectually.

Sometimes INTJ Types Are Too Confident

This distance associated with this MBTI test-assessed personality type can occasionally progress to the point of negativity. INTJ types can close themselves off so much that they stop revealing what they are thinking/how they are coming to certain conclusions, which can make it seem as though they are simply rushing through a task. They can often do just that—jumping to underdeveloped endings without considering all new or present information. This flaw can also cause Myers-Briggs test assessed INTJ types to overlook important data and facts necessary to achieve their goals.

Their high level of competence coupled with their big-picture way of thinking can sometimes cause problems for this Myers-Briggs type. Because so many of their ideas are long-term, INTJ type ideas can occasionally lack the ability to fully come to fruition.

In their relationships with others, MBTI Test-assessed INTJ Personality Types may come off as judgmental, especially to those who aren’t as openly enthusiastic about the INTJ types ideas or intelligence. If they feel that others are not viewing them as highly as they view themselves, there is also a chance that they will not necessarily provide the level of feedback that that individual may need. However, by concentrating on developing their Sensing and Feeling, the INTJ type may fashion more intimate connections with their peers, spending less time in their heads and more time engaging with the world around them.

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator INTJ personality type uses their big-picture thinking along with their logical problem-solving skills to succeed in a variety of occupations, usually those requiring scientific reasoning/understanding and those that involve building or creating something scientifically tangible. For these reasons, Myers-Briggs Test assessed INTJ types often find themselves choosing careers such as plant scientist, engineer, medical scientist, internist, or architect. MBTI test INTJ types also find themselves leaning towards those professions that require them to hold an authoritative position or a leadership role, such as a management consultant or a top executive.

To be successful in these problem-solving careers, Myers-Briggs test INTJ types must learn to consider short-term goals and opportunities as well as their already over-arching, long-term goals. This can include immediate priorities, career choices that the INTJ values but may not consider rational, and present values that INTJ type may be neglecting in favor of their long-term vision. Creating immediate and long-reaching goals for yourself can help you level your thinking and focus more on the moment.

To be successful in these problem-solving careers, Myers-Briggs test INTJ types must learn to consider short-term goals and opportunities as well as their already over-arching, long-term goals. This can include immediate priorities, career choices that the INTJ values but may not consider rational, and present values that INTJ type may be neglecting in favor of their long-term vision. Creating immediate and long-reaching goals for yourself can help you level your thinking and focus more on the moment.

Furthermore, this MBTI personality type may have a hard time dealing with sudden life changes or events. By allowing yourself time to think about immediate goals and surprising situations without focusing solely on the long-term outcome, you can be ready for unforeseen circumstances that may come their way.

One of the most important strategies that the Myers Briggs Type Indicator test INTJ type can implement to be successful in the workplace is to open themselves up to new people, new experiences, and new ideas. If you find yourself closed off or antisocial in the work environment, slowly opening yourself to other networks and creating personal relationships with those around you can help you become a more well-rounded employee.

How accurate is this?

Actually, it makes me look like a bit of an asshole. Far from perfect. A bit of a get-er-dun prima-donna when, in fact, my biggest criticism over the years is that I’m too nice of a guy for my own good. Anyway, it was a good mental exercise which made me think for awhile, and I got a kick outa being matched with notable characters with the same personality. Factual ones were Rudy Giuliani (Good Gawd), John F. Kennedy, and Hannibal— leader of the Carthaginians. Fictional characters were the protagonist and antagonist in Silence Of The Lambs, Clarise Starling and…. yeah — Hannibal Lector.

So, I challenge you. You can have a FREE psychological analysis just like mine. Go ahead and take the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator® Test at:

- Humanetrics — http://www.humanmetrics.com/cgi-win/jtypes2.asp

- My Personality Test — http://www.my-personality-test.com/personality-type/?gclid=CM2N_4CetsgCFQhsfgodXiEGjw

- Truity Type Finder — http://www.truity.com/test/type-finder-research-edition

At very least, it’s a buncha fun. C’mon DyingWords group. Take the test ‘n tell us who you are!