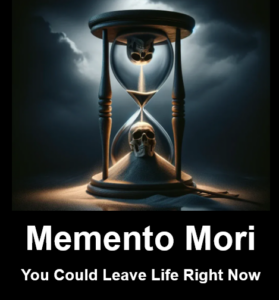

Memento Mori, translated from Latin, means “Remember, you must die”. It’s a wake-up that your life course could be radically altered and end at any moment. Our lives are impermanent, in constant flux and change, flowing through time towards entropy and inevitable death that might happen without warning. Memento Mori — You could leave life right now.

Memento Mori, translated from Latin, means “Remember, you must die”. It’s a wake-up that your life course could be radically altered and end at any moment. Our lives are impermanent, in constant flux and change, flowing through time towards entropy and inevitable death that might happen without warning. Memento Mori — You could leave life right now.

Recently, an acquaintance passed away. It shook our group as Rick, a likeable and apparently healthy man in his sixties, was suddenly diagnosed with esophageal cancer. Within a week, Rick was gone.

It made me reflect on my own mortality. I do this as part of my stoicism studies. As a student of stoicism, I carry a Memento Mori medallion in my pocket. I got it through Ryan Holiday who hosts the website and podcast called The Daily Stoic.

Memento Mori isn’t meant to be macabre. It’s a positive philosophical exercise to reflect on being in the moment and living life to the fullest. One measure of success is being free to live your life as you see fit and tchotchkes, or bric-a-brac prompts like this gold medallion, help keep me mindful of mortality and to live life in accordance with nature—in accordance with reason and harmony which is fundamental to stoicism.

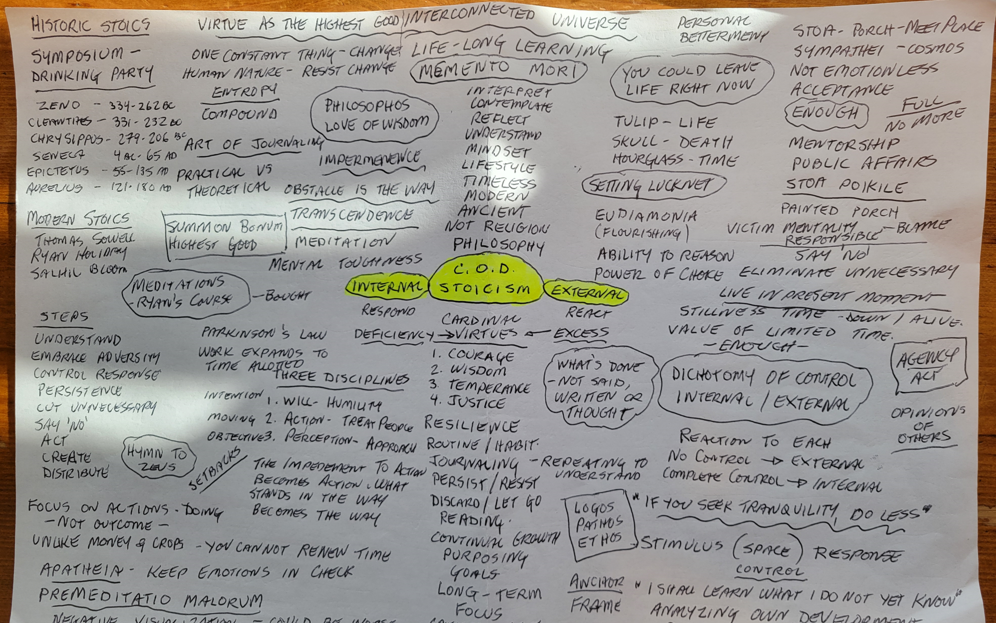

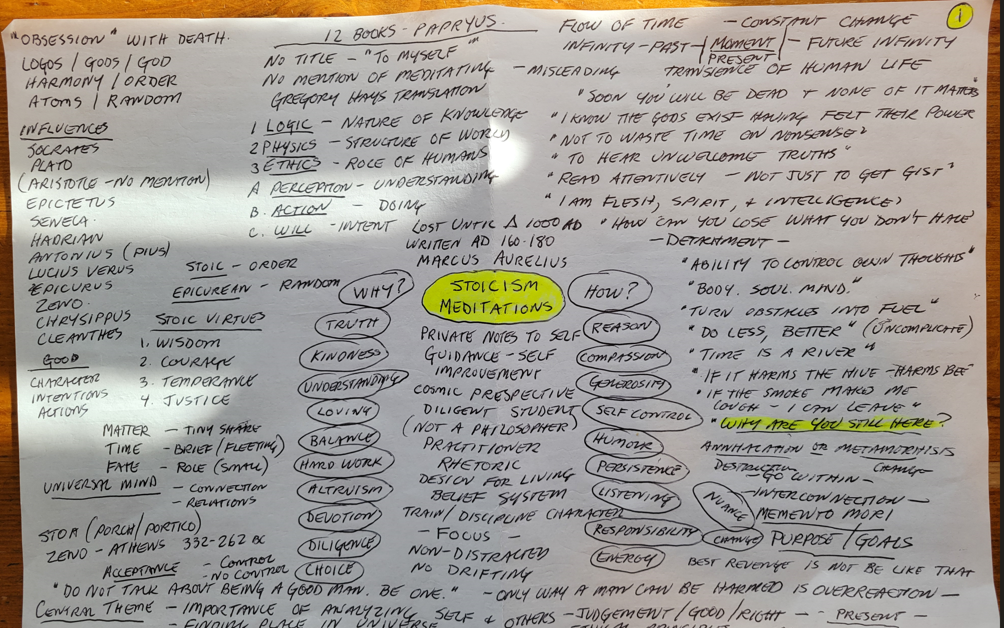

Some time ago, I wrote a post titled Stoicism — A Philosophy, Not a Religion. I’m not going to go further into stoic principles. You can read them by clicking here. What I’m doing today is exploring the origin of Memento Mori and offering some advice on how you can use an old Latin phrase to help guide you through a wonderful, appreciative life.

According to a trusted source, the Galileo Galilei Institute in Turin, Memento Mori originated as an ancient Roman custom. When a victorious general returned from a battle, he was paraded through the streets of Rome in a chariot to honor his achievements. However, that praise and adulation could dent his hubris (go to his head) so a slave stood behind the general whispering in his ear, “Respice post te. Hominem te memento mori”. Or “Remember that you are a man who must die”.

Over centuries, the Latin phrase has been repeated among many cultures, in different languages, but always with the same meaning. Remember, you must die.

In the 17th century, for example, in the cloistered order of Trappist friars, they repeated “Memento Mori” to each other while they dug their graves, bit-by-bit, day-by-day. It was always to keep their death in mind and not lose sight of the impermenance and value of life.

During the Renaissance period of Europe, a dance genre called Danse Macabre was extraordinarily popular. People would dress as skeletons and waltz through the streets, impersonating death and singing praise to Memento Mori. One of the great art works of the era, Vanitas, portrays Memento Mori as a tulip for life, a skull for death, and an hourglass for time.

In simple terms, Memento Mori serves as a personal prod to be mindful and present in any given moment. It’s not to be depressing about losing your life. Rather, Memento Mori is a tool to create priority and meaning. It’s to gain perspective on what’s important and what’s not important.

Death doesn’t make life pointless. Instead, introspection of death shows how purposeful life is—what our lives are capable of and what we can accomplish with the time we’re granted—a reflection about the temporaryness of life and how we can live our moments with intention, courage, and gratitude.

The reality of death is it’s one of life’s guarantees. (So are taxes.) Death is the great equalizer. No matter where you were born, into what class, how rich or poor you are, how clever or dim, how famous or obscure, or what you did with your life, the Grim Reaper eventually calls.

What you do with your life, and spend your time, is one of life’s freedoms. Aside from the gene cards you were dealt at birth, you are the master of your fate. And you can use the Memento Mori concept to your benefit. Here are some practical tips:

Daily Reflection. Set aside a few minutes each day to contemplate the impermanence of your life and the inevitability of your death. This helps you stay grounded, lets you prioritize your time and tasks, and lets you put energy into what’s important in your life.

Practice Gratitude. Memento Mori encourages you to appreciate the people, opportunities, and experiences in your life. You can cultivate gratitude by expressing thanks for the things you cherish and the time you have to enjoy them.

Journal. One of the core stoic practices is to maintain a daily journal. Writing down your thoughts, including your reflection and gratitude, gives you clarity, focus, and purpose.

Mindful Decision Making. Use Memento Mori when faced with decisions, both large and small, as a guiding principle to evaluate choices and set priorities. Ask yourself if your time were limited, would you take on that activity or give it a pass.

Embrace Courage. If facing death, how would you respond? Memento Mori can help you overcome fear and weigh risks. By remembering your time is limited, you may be more inclined to follow opportunities and experience new challenges.

Foster Deeper Connections. Recognizing that time is fleeting will make you more appreciative of family, friends, neighbors, and so forth. Remember that Memento Mori applies to them too.

Cultivate Detachment. Reminding yourself that you can leave life right now puts a new light on material possessions, social status, and achievements. This awareness fosters a deep appreciation for what’s truly important in life and, equally, what’s not.

Personal Growth. Memento Mori can inspire you to focus on self-improvement and embracing the four cardinal virtues: temperance, courage, justice, and wisdom. By understanding the impermanence of life, you’ll be motivated to continually strive to be the best version of yourself.

Remembering Memento Mori daily can be an ode to life. It encourages us to stop wasting time in pursuing other people’s goals, hoarding material possessions, or worrying about trivial matters. It’s about being free to live your life, and spend your time, as you see fit.