Pope Francis recently passed away. He lay in state at the Vatican, in an open casket, for three days while over a quarter million people filed by and respected his body. Francis remained remarkedly well preserved unlike Pope Pius XII who died in 1958 and became the poster boy of morbid mortuary fails and the most grotesque example of how not to embalm a pope.

Pope Francis recently passed away. He lay in state at the Vatican, in an open casket, for three days while over a quarter million people filed by and respected his body. Francis remained remarkedly well preserved unlike Pope Pius XII who died in 1958 and became the poster boy of morbid mortuary fails and the most grotesque example of how not to embalm a pope.

When I saw newsfeed afterlife photos of Pope Francis, eyes closed, dressed in red vestments, wearing a bishop’s miter, and lightly clutching a rosary in his bare hands, I was struck by how life-like he appeared. Having considerable experience around dead bodies and knowing the decomposition process, the first thing in my mind was, “Wow, they did a great job of embalming. I wonder what process they used?”

It was minimal invasive thanatopraxia, not the never-tried-before embalming method employed on Pius XII that resulted in the most undignified incident in papal history which horrified the faithful clergy and nauseated the public mourners.

We’ll look at what went ghastly wrong with incorpsing Pope Pius XII but first let’s review the history of human body preservation and the science of decomposition.

The Ancients and the Afterlife

The practice of embalming goes back more than 6,000 years. The Egyptians get most of the credit, and rightfully so. They mastered a method that mummified bodies so well we’re still unwrapping their secrets today. Of interest, read the Dyingwords article titled The Lost Art of Making Mummies.

Back then, embalming wasn’t just a medical procedure—it was a spiritual rite. The Egyptians believed in an afterlife that required a well-preserved vessel for the soul. So, they developed a meticulous process involving evisceration (organ removal), desiccation (drying), and resin-based sealing.

Here’s what that looked like:

- The brain? Removed through the nostrils using a hooked instrument.

- The intestines, stomach, liver, and lungs? Taken out through an abdominal incision and often placed in canopic jars.

- The heart? Sometimes left in, sometimes not. That depended upon the dynasty and theology of the day.

- The body? Packed with natron salt for 40 days to dehydrate the tissues before being wrapped in linen soaked in oils and resins.

The results? Bodies that could last for many millennia. Not pretty, but persistent.

Other cultures had their own versions. The Chinchorro of South America were embalming their dead a thousand years before the Egyptians. Greeks and Romans experimented with honey, spices, and lead-lined coffins. The Chinese used mercury. Everyone wanted to cheat time, but none did it with quite the same ritualistic precision as the Pharaohs’ embalmers.

From Sacred to Sanitary — The Middle Ages to the Renaissance

Once Christianity took hold in Europe, embalming practices changed. The early Church frowned on mutilating the body, which was seen as a sacred temple. Instead, burial became the norm, often with little more than prayers and herbs.

But during the Middle Ages, embalming resurfaced—this time for more pragmatic reasons than spiritual ones. Kings, nobles, and church leaders often died far from home, and the only way to get them back without stinking up the countryside was to pack the body with preservatives. That usually meant alcohol, myrrh, or wax, wrapped tightly to delay decay.

Then came the Renaissance. Along with new art and new ideas came new interest in human anatomy. Surgeons, scientists, and physicians began dissecting cadavers, and they needed a way to keep bodies from decomposing before their scalpels could learn anything.

This is when we saw the rise of arterial injection techniques, particularly in Italy. Instead of just treating the surface or packing the cavities, early anatomists began experimenting with injecting preservative fluids into the blood vessels—a precursor to modern embalming.

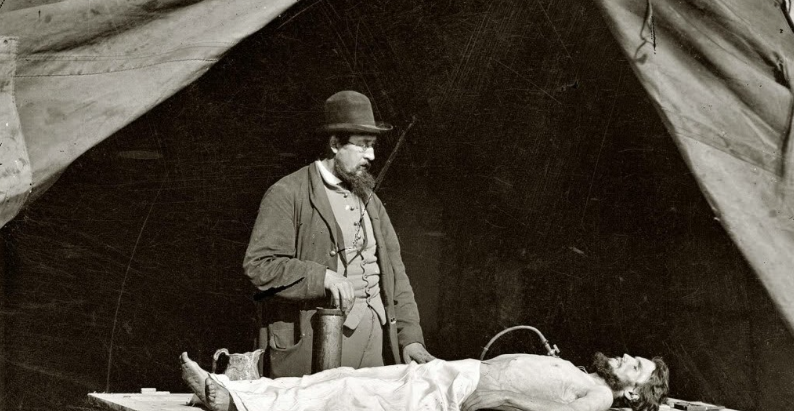

Modern Embalming Is Born — Thanks to War and a Cold Body Count

The real shift toward modern embalming came with the American Civil War (1861–1865). Thousands of soldiers were dying far from home, and grieving families wanted their boys brought back in a condition fit for burial. Enter Dr. Thomas Holmes, often called the “Father of Modern Embalming in America.”

Holmes developed a formula based on arsenic and alcohol, which allowed him to embalm bodies quickly and effectively. He reportedly embalmed over 4,000 Union soldiers during the war. Word got out. Embalming became a recognized profession, and traveling embalmers followed the carnage across battlefields.

After the war, funeral homes emerged as legitimate businesses, and embalming became standard practice. The U.S. in particular embraced it more than any other country. By the early 20th century, embalming was no longer a battlefield necessity—it was a cultural expectation.

The Rise of Formaldehyde and the Funeral Industry

In the early 1900s, formaldehyde replaced arsenic as the go-to embalming chemical. Arsenic, after all, had a nasty side effect—it poisoned the ground and anyone who tried to exhume the body. Formaldehyde was seen as safer (relatively), more stable, and more effective at halting decomposition.

The technique was refined:

- Arterial injection of embalming fluid through the carotid artery.

- Drainage through the jugular vein.

- Cavity embalming with a trocar (a hollow needle) to remove and replace internal fluids with preservatives.

- Surface treatments and reconstruction, particularly for trauma or decomposition cases.

By mid-century, embalming was as routine in North America as brushing teeth. A new profession emerged—the embalmer as technician, equal parts chemist, artist, and psychologist.

But embalming wasn’t just about science. It became part of the “death care” industry, an entire system designed to sanitize and soften death’s realities for the viewing public.

Present Day — From Science to Aesthetics

Modern embalming is as much about presentation as preservation. The goal is often to create a “memory picture”—a final, peaceful image for loved ones. This is where cosmetic restoration comes in.

Today’s embalming fluids are far more sophisticated:

- Formaldehyde-based solutions are still used, but often mixed with glutaraldehyde, alcohols, humectants (moisturizers), and dyes.

- Specialized chemicals are used depending on the body’s condition—edema, jaundice, emaciation, or post-autopsy cases each require different formulations.

Prep rooms are sterile and methodical:

- Embalmers wear PPE.

- The process is documented.

- Ventilation systems remove harmful vapors.

- Green burial movements have also influenced the use of lower-toxicity chemicals.

But here’s the truth: no modern embalming is permanent. Today’s best results will preserve a body for 1 to 2 weeks in viewable condition. In extreme cases—with refrigeration, sealing, and advanced fluids—a month or more is possible. But eventually nature, or entropy, always wins.

The Best Modern Results — What Actually Works

If you’re wondering what produces the best results today, here’s the truth from someone who’s worked with too many dead to count:

- Combination of arterial and cavity embalming is essential.

- Formaldehyde-based fluids, when balanced with humectants and surfactants, remain the gold standard.

- Rapid intervention after death—the sooner the body is embalmed, the better the result.

- Refrigeration slows decomposition and supports the embalmer’s efforts.

- Cosmetic artistry—restorative work, airbrushes, facial reconstruction—is often the difference between an acceptable viewing and a traumatic one.

It’s not just chemistry—it’s craftsmanship.

Final Thoughts from the Cold Side of the Table

Embalming isn’t a morbid curiosity. It’s a window into how we handle death, both literally and philosophically. From the sands of Giza to the stainless of modern morgues, embalming has always been a human response to the ultimate truth—that we’re here for a short while, and then we’re gone.

We embalm not just to preserve the body, but to hold on to meaning.

So, whether you see it as sacred, sanitary, or strictly scientific, embalming is part of the long story of what it means to live… and what it means to say goodbye.

The Science of Human Body Decomposition — When Nature Takes the Wheel

If embalming is our attempt to delay death’s effects, decomposition is nature’s way of reminding us who’s really in charge.

I’ve seen more bodies in more stages of decomposition than most folks care to imagine. And no two look—or smell—quite the same. But under all the grime, there’s a cold, clear science to what happens when the human machine shuts down and the decomp clock starts ticking.

Whether embalmed, buried, burned, or left to the elements, every body biologically breaks down. Understanding decomposition isn’t just a matter of curiosity—it’s crucial in criminal investigations, disaster recovery, and even public health. So, let’s walk through it, step by step, from the moment the heart stops to the final handful of dust.

The Moment of Death — The Clock Starts Ticking

Death, biologically speaking, is the point at which circulation and respiration stop, halting oxygen delivery to cells. Without oxygen, the body immediately begins to unravel. Two major processes take over:

- Autolysis – self-digestion by enzymes already present in the body.

- Putrefaction – microbial activity, mainly from bacteria in the gut and respiratory tract.

These aren’t horror movie concepts. They’re predictable, measurable, and driven by temperature, environment, and the body’s own internal makeup. Here are the five decomposition stages.

Stage One: Fresh (0–3 Days Postmortem)

This is the “quiet” phase. From the outside, the body may look peaceful. But inside, the breakdown has already begun.

- Algor mortis – body temperature drops about 1.5°F per hour until it matches ambient surroundings.

- Livor mortis – blood settles in the dependent parts of the body, creating purplish staining.

- Rigor mortis – muscles stiffen due to a lack of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and calcium ion accumulation. This starts 2–6 hours after death and fades after 24–48 hours.

- Internally, cells burst. Digestive enzymes start dissolving organ linings. The gut bacteria—primarily Clostridium and E. coli—begin a feeding frenzy.

There’s no smell yet. But it’s coming.

Stage Two: Bloat (3–7 Days Postmortem)

This is where decomposition makes itself known. Gas accumulation, driven by bacterial metabolism, swells the body like a balloon.

- Hydrogen sulfide, methane, cadaverine, and putrescine are released—these are the famous “death gases” responsible for the foul odor. You’ll never forget that rotting flesh smell.

- The face distorts. Tongue protrudes. The abdomen balloons.

- Skin may blister, slough, or split. Marbling of the skin (a green-black web-like pattern) forms due to hemolysis of red blood cells and gas tracking along vessels.

- The body may leak fluids from the nose, mouth, orifices, and ruptured skin.

Under pressure, a body may rupture or even partially explode—especially in sealed environments or warm temperatures. Yes, this really happens. I’ve seen it, and it happened to Pius XII.

Stage Three: Active Decay (7–20 Days Postmortem)

Now the body is collapsing in on itself.

- Tissues liquefy. Organs turn to mush. The skin turns green-black or slips off in sheets.

- Maggots (from blowflies and flesh flies) are often present unless the environment is sealed or too cold.

- The volume of insect activity and gas discharge peaks.

- Skeleton begins to show through as soft tissue breaks down.

The odor is at its worst here. It’s a cocktail of ammonia, sulfur, and organic acids—one that clings to your nose hairs and your long-term memory.

Stage Four: Advanced Decay (20–50 Days Postmortem)

Most of the soft tissue is gone.

- Insect activity slows as the body becomes less nutritious.

- Fluids are mostly gone. What’s left is dried tissue, skin, cartilage, and partially skeletonized remains.

- Soil beneath or surrounding the body may show cadaver decomposition islands—patches rich in nitrogen and fatty acids, often visible to forensic searchers.

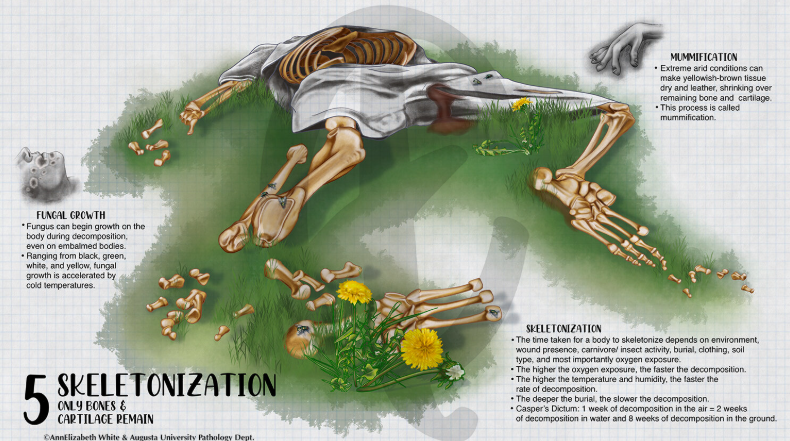

Stage Five: Dry/Skeletal (50+ Days Postmortem)

Now we’re down to bone and maybe some desiccated tendons or ligaments. This is the final state, though the timeline can vary wildly depending on conditions.

- In dry, cold, or arid environments, skeletonization can take years.

- In hot, humid, or insect-rich environments, it can occur in weeks.

Bones themselves can persist for centuries, but they don’t escape the laws of nature. Eventually, they weather, flake, and return to the earth—especially in acidic soil.

Factors That Influence Decomposition

Decomposition is not a fixed timeline. It’s shaped by many factors:

- Temperature – heat speeds it up; cold slows it down.

- Moisture – promotes bacterial and insect activity.

- Oxygen – essential for some microbes; absence can slow decay.

- Burial depth – deeper bodies decompose slower.

- Container – sealed caskets trap gases; open-air exposure accelerates breakdown.

- Body fat – fatty tissue decomposes faster and can promote adipocere formation (a soap-like substance often called grave wax).

- Injuries or trauma – open wounds speed microbial and insect access.

Postmortem Chemistry: What’s That Smell?

That unforgettable odor of death? It comes from a chemical symphony:

- Putrescine and cadaverine – produced by amino acid breakdown.

- Hydrogen sulfide – rotten egg smell and the odor added to natural gas.

- Methanethiol – stinks like rotting cabbage.

- Dimethyl disulfide and trisulfide – pungent sulfur smells.

- Butyric acid – rancid butter or animal vomit.

All are volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and all are part of the forensic signature that trained dogs, insects, and even analytical devices can detect.

Final Thoughts on Final Decay

There’s something brutally honest about decomposition. It strips away pretense, makeup, and all our biological illusions. It’s not pretty. It’s not poetic. But it’s real. And it’s one of the few universal truths you can bet your bones on.

From a coroner’s point of view, decomposition isn’t just a horror show. It’s a clock, and every stage offers clues: time since death, cause of death, even location and movement of the body. It’s nature’s forensic diary—and if you know how to read it, it speaks volumes.

In the end, decomposition is the great equalizer. It doesn’t care if you were a pope or a pauper, a saint or a sinner. You’ll break down just the same.

Unless, of course, an embalmer gets to you first.

How Not to Embalm a Pope — The Case of Pius XII

You’d think the Vatican—of all institutions—would have mastered the art of saying goodbye. After all, they’ve been burying popes for centuries. But in 1958, when Pope Pius XII died, his body’s final chapter became the most infamous embalming apocalypse in modern history.

It wasn’t just a bad job. It was a botched-beyond-belief spectacle that left mourners gagging, clergy horrified, and even hardened coroners shaking their heads. The embalming of Pius XII was so catastrophically mishandled, it didn’t just mar his memory—it changed the way popes have been prepared for viewing ever since.

The Death of a Pope

Pope Pius XII died on October 9, 1958, at Castel Gandolfo, the papal summer residence outside Rome. He was 82 years old and had ruled the Church through the Second World War and into the height of the Cold War.

According to Catholic tradition, the body of a deceased pope is to be displayed publicly for several days so the faithful can file past and pay their respects. This requires excellent preservation—not just for the dignity of the Church, but for the viewing masses who line up for hours in the Roman heat.

So, what went wrong?

The “Secret” Embalming Method

Instead of entrusting the body to an experienced mortician or medical professional, the task was assigned to Riccardo Galeazzi-Lisi, the pope’s personal physician. Galeazzi-Lisi, whose ego reportedly rivaled his credentials, decided to use a method that was unorthodox, untested, and ultimately disastrous.

He called it a “natural embalming technique.” In reality, it was frightening—an amateurish blend of foundationless folklore and stunningly stupid science.

Here’s what this guy did:

- He refused to use formaldehyde or traditional embalming chemicals.

- Instead, he wrapped the pope’s body in plastic sheeting. Basically, he put the pope in a plastic bag.

- Inside the bag, he inserted sacks of herbs and spices, supposedly mimicking ancient Roman and Egyptian preservation techniques.

- To prevent putrefaction, he reportedly coated the body with oils and resins, then placed the pope-in-a-bag in a room cooled only by open windows—not refrigeration.

He claimed this “natural mummification” would slow decomposition while maintaining the pope’s appearance. It didn’t.

The Results: A Decomposition Disaster

Within 24 hours, the signs of failure were obvious. The bound body rapidly generated runaway heat and began to bloat. By the time Pius XII was moved to St. Peter’s Basilica for public viewing, the damage was irreversible.

Here’s what witnesses saw and smelled:

- The pope’s skin turned greenish-black.

- His facial features swelled grotesquely from trapped gases.

- The stench was so overpowering that Swiss Guards reportedly fainted.

- Fluids leaked from the orifices.

- His nose and his fingers detached.

- His edematous (bloated, distended, engorged) abdomen ruptured from extreme internal gas pressure, emitting a giant and long-lasting juicy wet-fart sound, causing one priest present to later say “he actually exploded.”

There are credible accounts that the onlooking public recoiled in horror. Vatican officials tried to cut the viewing short and limit media access, but the damage—both physical and reputational—was done. Pius XII’s once-solemn lying-in-state turned into a macabre cautionary tale.

The Fallout: Scandal and Reform

The scandal reached international press. Photographs were suppressed. Riccardo Galeazzi-Lisi was quickly discredited and banned for life from practicing medicine by the Italian Medical Council. He was also dismissed in disgrace from the Vatican.

But the greater consequence was institutional. The Catholic Church quietly but firmly re-evaluated its postmortem protocols for papal embalming. The old approach—personal physicians using eccentric methods—was scrapped in favor of professional, discreet, and clinically proven techniques.

From that point forward:

- Certified embalmers and anatomical experts were brought in.

- Formaldehyde-based arterial embalming became standard.

- Refrigeration and climate control were mandated for extended viewings.

- Papal funeral procedures were tightened and codified.

In effect, the failure of Pius XII’s embalming modernized the Vatican’s death care procedures.

The Legacy of a Botched Job

Pius XII was known for his solemn intellect and his deep concern for order, tradition, and dignity. Ironically, his final public appearance became a chaotic debacle that overshadowed the sacred rite it was meant to uphold.

But in the strange way history works, his botched embalming wasn’t entirely in vain. It forced the Church to confront the realities of death—not in theology, but in biology.

Since then, no pope has decomposed in public. And when Pope John Paul II, Pope Benedict XVI, and even Pope Francis lay in state for days, their bodies appeared serene, preserved, and untroubled by the putrified rot that defamed Pius XII.

After Pius XII, the Vatican accepted what every coroner knows. Death and decomposition are natural and unforgiving. And if you want to embalm a pope, there’s no substitute for doing it right.