What really happened to Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 is aviation’s great mystery. On March 8, 2014, the doomed Boeing 777-200ER left Kuala Lumpur bound for Beijing, China with 239 souls on board—227 passengers and 12 crew members. They never made it. Nearly ten years later, their disappearance remains unexplained. Either it’s a tragic accident of unprecedented proportion with no plausible reason, or MAS370 is a mass murder.

What really happened to Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 is aviation’s great mystery. On March 8, 2014, the doomed Boeing 777-200ER left Kuala Lumpur bound for Beijing, China with 239 souls on board—227 passengers and 12 crew members. They never made it. Nearly ten years later, their disappearance remains unexplained. Either it’s a tragic accident of unprecedented proportion with no plausible reason, or MAS370 is a mass murder.

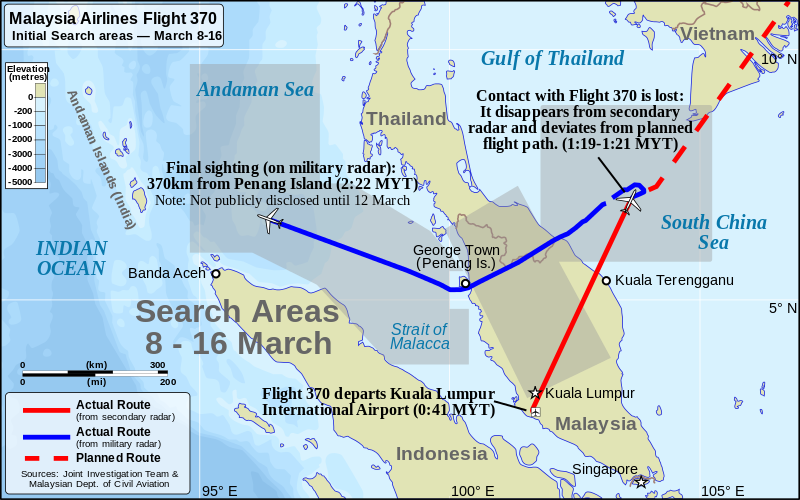

Malaysia Air Flight 370 (also called MH370) routinely lifted off KUL runway 32R at 12:42 am local time. The jetliner headed north-northeast for a 5.5-hour trip crossing the South China Sea towards Vietnam and on a course for China’s capital city. Its predicted arrival was 6:10 am with Beijing being in the same time zone as Kuala Lumpur.

MAS370’s first 27 minutes appeared normal from Kuala Lumpur Air Traffic Control (ATC) voice and radar records. The last radio transmission between the airliner and ATC Kuala Lumpur was at 1:19 am. This was the pilot acknowledging the controller’s direction to turn over Flight 370’s supervision to Vietnamese airspace at ATC Ho Chi Minh City on the 120.9 radio frequency. The last words from the plane were, “Goodnight. Malaysian three seven zero.”

At this time, the jetliner leveled to a cruising altitude of 35,000 feet with a ground speed of 510 knots. This was normal for the flight. However, at 1:22 am something completely abnormal suddenly occurred. Malaysia Air Flight 370’s transponder stopped, and the plane’s electronic image vanished from ATC Kuala Lumpur’s radar screen.

At this time, the jetliner leveled to a cruising altitude of 35,000 feet with a ground speed of 510 knots. This was normal for the flight. However, at 1:22 am something completely abnormal suddenly occurred. Malaysia Air Flight 370’s transponder stopped, and the plane’s electronic image vanished from ATC Kuala Lumpur’s radar screen.

A vanishing transponder image should raise a red flag and set off alarms. This, however, was an unusual situation because the airplane was at a critical location where it was changing from one Area Control Center (ACC) to another. Coincidentally, it also happened at a moment where the responsible controller at ATC Kuala Lumpur was distracted by another matter and didn’t catch Flight 370’s transponder loss.

But ATC in Ho Chi Minh noticed the vanishing transponder. They were expecting the flight and knew it was being handed over as it flew into their airspace. What the Vietnamese controller didn’t know was a formal protocol that they were to immediately notify Kuala Lumpur ATC of the issue. Instead, ATC Ho Chi Minh repeatedly tried to radio Flight 370 but got no response. 18 minutes passed after the transponder stopped before ATC Ho Chi Minh telephoned ATC Kuala Lumpur and alerted them to the disappearance.

Hindsight is usually 20/20, but there was considerable confusion—if not incompetence—within both control centers. Kuala Lumpur looked at the issue as being in Vietnamese airspace when it vanished and therefore their jurisdictional problem. Ho Chi Minh viewed it as a Malaysian airliner belonging to them. By 6:10 am, Flight 370 was overdue in Beijing, and it wasn’t until 6:32 am before Kuala Lumpur’s Aeronautical Rescue Coordination Center was notified to begin an emergency response. 5 hours and 10 minutes passed since Flight 370 disappeared from both ATC radar screens.

The Search Begins

The search for Malaysia Air Flight 370 is the most extensive and expensive aviation hunt in history. Officially, the Malaysian government headed the search and the subsequent investigation. Unofficially, Australia took the lead because of their resource capabilities of searching the air and the sea. Many countries joined in including the United States, France, Great Britain, China, Vietnam, and Thailand.

Between March 08 and April 28, the combined forces involved 19 naval vessels and 347 aerial sorties. They crisscrossed 1,800,000 square miles of ocean and land surface as well as examining a seafloor area with sonar and bathymetric methods. Not a trace of the plane was found during that period.

Between March 08 and April 28, the combined forces involved 19 naval vessels and 347 aerial sorties. They crisscrossed 1,800,000 square miles of ocean and land surface as well as examining a seafloor area with sonar and bathymetric methods. Not a trace of the plane was found during that period.

Initially, the search focused on the location where the transponder contact stopped. From there, the searchers followed a logical path along the airplane’s destined route of approximately 38° northeast over the South China Sea. It took approximately a week until an investigation into radar records showed something drastically different.

The aviation industry and national defense forces use two radar types. One is primary radar that sends a signal that “pings” or bounces off an object like a plane. When struck by a primary radar wave, the aircraft has no choice but to be seen. Primary radar is the preferred choice of all military installations. The enemy can’t hide except under stealth conditions.

Civilian air traffic controllers like the secondary radar system. This involves cooperating airplanes volunteering a data-rich signal through their on-board transponders. A transponder signal gives the controller vital details like the crafts identity, its altitude, flight plan, speed and so forth. The problem with secondary radar and transponder signals is they can be voluntarily turned off.

It was soon evident Flight 370’s transponder was intentionally disabled. Primary radar images and records obtained from the Thai, Viet and Malaysian military showed 370 stayed in the sky for a long time after its transponder stopped. Military radar proved Flight 370 made an abrupt left turn immediately after the secondary civilian radar lost the track. Flight 370 turned into an extremely sharp bank towards the southwest and flew on an approximately 230° course back over Malaysia and to Kuala Lumpur’s northwest.

Thai and Malaysian military radar records showed Flight 370 passing over the island of Penang at 1:52 heading out and over the Strait of Malacca. Just past Penang, Flight 370 again altered course to a west-northwest bearing of approximately 275°. This alteration avoided crossing Indonesia. The last primary contact was at 2:22 am when Flight 370 left the outer limits of the Malaysian military’s radar. At that time, the plane was at 29,500 feet, traveling at 491 knots and located 285 miles northwest of the Penang military installation.

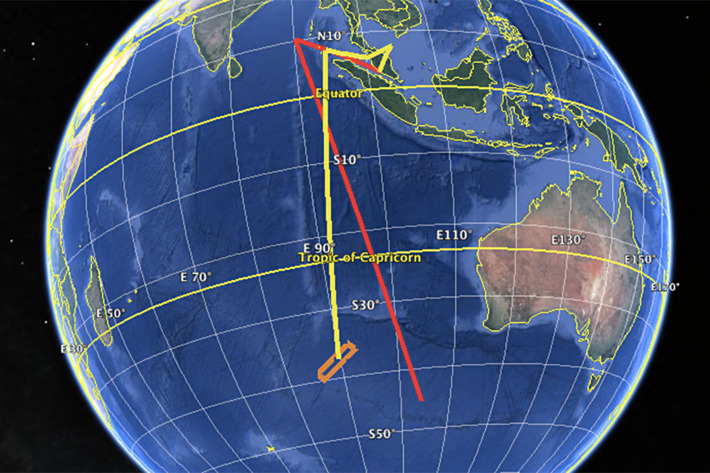

This might have been the last radar contact with Malaysia Air Flight 370. But it was far from the last time it was tracked. Two minutes after flying off primary radar, the airplane automatically connected with a communications satellite which continued to monitor the plane until 8:19 am. That’s 6 hours and 57 minutes after the transponder went silent.

The Inmarsat Satellite Information

The satellite was a British-based Inmarsat-3F1 in geostatic orbit above the Indian Ocean. The Boeing 777 was equipped with an Aeronautical Satellite Communication (SATCOM) system that allowed cockpit voice communication and critical in-flight data to be sent from anywhere in the world. Boeing designs these jets to be always in constant electronic contact regardless of where they are.

It’s impossible to get lost in a 777, but it’s easy to hide in one—if the operator knows what they’re doing. Aside from the transponder going silent at 1:22 am, the aircraft’s electronic systems were also disabled. This lasted until 2:25 am—just after leaving the last grasp of primary radar range from Penang.

The Inmarsat was minding its own business when it got an unsolicited ping from Flight 370’s Satellite Data Unit (SDU). As it’s designed to do, the satellite recognized Flight 370’s “log-on request” and responded with a protocol interrogation process known in the industry as a “handshake”. The plane’s SDU automatically replied to Inmarsat and the plane & satellite entered into an agreement of regular 30-minute interval check-ins. It continued until 8:19 am when contact was permanently broken.

The Inmarsat was minding its own business when it got an unsolicited ping from Flight 370’s Satellite Data Unit (SDU). As it’s designed to do, the satellite recognized Flight 370’s “log-on request” and responded with a protocol interrogation process known in the industry as a “handshake”. The plane’s SDU automatically replied to Inmarsat and the plane & satellite entered into an agreement of regular 30-minute interval check-ins. It continued until 8:19 am when contact was permanently broken.

Human monitors at Inmarsat’s ground monitoring station in Perth, Australia immediately recognized an unidentified airplane had unexpectedly contacted them. They made two ground-to-aircraft telephone calls to Flight 370. The plane’s SDU acknowledged both, but no one on board the mysterious jetliner answered.

Inmarsat continued 30-minute “handshake” contacts with Flight 370. At 7:13 am the Perth station tried another ground-to-air phone call. It, too, was unanswered. At 8:19 am there was a log-off interruption from Flight 370 followed by an immediate log-on request and another interruption.

It took a week after Flight 370 disappeared to analyze the full Inmarsat information and put it to use in locating the plane’s final location when it signed-off at 8:19 am. Essentially, the Inmarsat data showed the first contact with Flight 370 right after it left conventional radar range. That was at 2:25 am and the Boeing 777’s location was approximately 300 miles northwest of Penang.

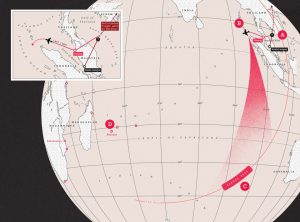

However, in the 3 minutes since going off military radar and connecting with Inmarsat, Flight 370 had drastically altered course. Now the jet was bearing approximately 190° in a south-southwest direction. It had made an 85° left turn once it was off military radar.

Inmarsat technicians spent a lot of effort analyzing data transmitted by Flight 370 in the period they tracked it. This was a difficult chore because the Inmarsat spacecraft was made to communicate with ships and planes, not to track them. They worked with principles called burst time offset (BTO) and burst frequency offset (BFO).

Ultimately, Inmarsat experts calculated a series of Doppler Arcs which gave them a high-probability flight line. By working with Boeing engineers, the team extrapolated information about the plane’s speed and fuel capacity. This allowed them to zero-in on a likely location where Flight 370 exhausted its fuel, extinguished its engines, and crashed into the sea.

The suspected crash site was in the Southern Indian Ocean. It was approximately 1,400 miles west of the Australian continent and about the same distance from the northern regions of Antarctica. This is one of the most remote ocean locations on Earth and an area where the seafloor was unexplored.

The suspected crash site was in the Southern Indian Ocean. It was approximately 1,400 miles west of the Australian continent and about the same distance from the northern regions of Antarctica. This is one of the most remote ocean locations on Earth and an area where the seafloor was unexplored.

With this apparently credible military radar and Inmarsat information, the search for Malaysia Air Flight 370 moved from the South China Sea to the rough and hostile waters of the lower Indian Ocean. The Australian Navy did its best to search for the telltale pings from the Boeing’s black boxes, however, the batteries had a 30-day energy period that expired. A private American company conducted a second underwater search but also came up empty-handed.

Debris from Malaysia Flight 370 Washes Up

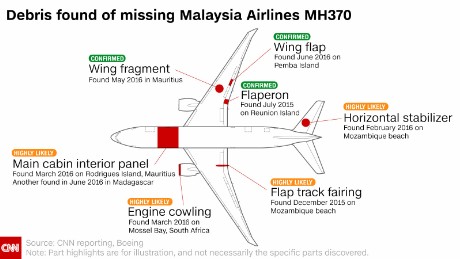

Despite the massive air and sea search done in the months after Flight 370 vanished, not one scrap of physical evidence surfaced to conclusively prove the plane had, in fact, crashed. That changed in July 2015 when an aircraft component called a “flaperon” washed up on a beach of Reunion Island. This remote volcanic landmass is a French protectorate situated 500 miles east of Madagascar and about 3,000 miles northwest from the calculated crash area.

A flaperon is a component from a jetliner’s trailing wing edge. It’s part of the air-braking system where flaps get lowered to slow the airplane down and give it more lift. French authorities who received the flaperon from Reunion’s shore made a conclusive connection to Flight 370 due to a serial number etched into the metal.

A flaperon is a component from a jetliner’s trailing wing edge. It’s part of the air-braking system where flaps get lowered to slow the airplane down and give it more lift. French authorities who received the flaperon from Reunion’s shore made a conclusive connection to Flight 370 due to a serial number etched into the metal.

This was the first proof that Flight 370 had crashed. Engineers were able to tell that the flaps were up, or in a non-extended position, when the jet impacted the water. They also concluded from the stress fracture damage that the plane had hit the water at high speed and in a downward, nose-first angle.

Finding a smashed part from Flight 370 was a devastating blow to families of the doomed passengers and flight crew. To this point, some held hope that somehow the plane’s disappearance had some other explanation than crashing and that somehow—somewhere—their loved ones survived and waited rescuing.

Over the following months of 2015 and 2016, more than 20 more demolished parts of the shredded passenger jet were found along Indian Ocean shorelines. Oceanographers familiar with wind, wave, tide, and current behavior tend to agree that the washed-up debris pattern was consistent with originating from the previously calculated crash location.

To this date, no bodies or personal effects of the victims have been found. There are no more planned searches, and the official investigations by the Malaysian government, their police and their transportation safety authorities have stopped. All acknowledge that Flight 370 crashed into the Indian Ocean, but none make any conclusion of why it happened. The official cause is listed as “Undetermined”.

What Caused Malaysia Air Flight 370 to Crash?

There are many theories about what caused Malaysia Air Flight 370 to crash. Some are far-out conspiracy BS like it being abducted by aliens or stolen by the Russians and parked in a secret hanger in Kamchatka. There are internet posts and podcasts concluding the plane was struck by a meteorite and vaporized. Some part-time sleuths suggest that the Malaysian government who owns the airline ordered it destroyed as part of a cover-up for reasons unknown.

Setting aside the inevitable conspiracy theories that always arise in high-profile events, there are only two reasonable explanations for Flight 370’s erratic behavior and ultimate fate. One is the airplane suddenly experienced a massive depressurization which sent the flight crew into an immediate hypoxia event rendering them oxygen-starved and unable to function. The other theory is that someone very familiar with operating a Boeing 777-200ER intentionally sabotaged the flight that caused 239 human deaths.

Setting aside the inevitable conspiracy theories that always arise in high-profile events, there are only two reasonable explanations for Flight 370’s erratic behavior and ultimate fate. One is the airplane suddenly experienced a massive depressurization which sent the flight crew into an immediate hypoxia event rendering them oxygen-starved and unable to function. The other theory is that someone very familiar with operating a Boeing 777-200ER intentionally sabotaged the flight that caused 239 human deaths.

The first scenario about catastrophic depressurization is worth exploring. An article in the respected journal Air & Space Magazine analyzes the mechanics of a depressurization event and how they’ve caused fatal air crashes in the past. It’s an interesting exercise in flight science but the article fails to deal with facts like intentionally disabling the transponder precisely when it happened and the erratic flight path which was certainly done by someone manually flying and aggressively handling a large commercial aircraft like a Boeing 777.

That leads to the other theory that a crew member went rogue. Before dismissing this as an impossibility, there are four previously recorded episodes of a flight crew member intentionally downing their plane and killing their passengers. They are:

- 1997 — Singapore Silkair Boeing 737

- 1999 — EgyptAir Flight 990

- 2013 — LAM Mozambique Airlines Flight 470

- 2015 — Germanwings Airbus in the French Alps

In these four cases, there was no pre-warning about the perpetrator’s awful intent. In hindsight of the investigation, though, there were signs of a troubled individual and considerable pre-planning. That seems to be the case with Malaysia Air Flight 370.

A Boeing 777 on short-haul flights only requires a two-person flight control crew. That’s the pilot-in-command, or captain, and the second-in-command known as the first officer. On fateful Flight 370, the first officer was Fariq Abdul Hamid and the captain was Zaharie Ahmad Shah. In Malaysian custom, they were known as First Officer Fariq and Captain Zaharie.

A Boeing 777 on short-haul flights only requires a two-person flight control crew. That’s the pilot-in-command, or captain, and the second-in-command known as the first officer. On fateful Flight 370, the first officer was Fariq Abdul Hamid and the captain was Zaharie Ahmad Shah. In Malaysian custom, they were known as First Officer Fariq and Captain Zaharie.

First Officer Fariq is a highly unlikely suspect to do anything as horrifying as intentionally crashing his plane and killing his people. Fariq was 27 years old and about to be married. He had flying experience on Boeing 737s and the AirbusA330 but only had 39 hours so far on the big 777. Fariq was a pilot-in-training on the triple-seven and under Captain Zaharie’s direct supervision.

The “Captain-Did-It” Theory

53-year-old Captain Zaharie, on the other hand, was highly experienced. He’d been with Malaysian Airlines for 33 years and had over 18,000 flight hours. A good deal of that time was as pilot-in-command on Boeing 777s. However, in his personal life, Zaharie showed signs of clinical depression and moving toward mental instability. His wife had left him, and he was living alone. Much of his off-hours were spent on his home-based computerized flight simulator.

At the request of Malaysian Air and Zaharie’s family, the FBI analyzed the history in Zaharie’s simulator hard drive. They found many plotted flights. One had the exact route fatal Flight 370 took. Zaharie simulated leaving Kuala Lumpur, then reached the radio hand-off position between Malaysian and Vietnamese airspace. Here, he made a hard left-hand turn and followed weigh-points that kept him on an international edge between Malaysia, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Thailand. That simulated flight plan effectively kept him from being intercepted by each country’s military fighter planes although he would have known they’d be monitoring him on primary radar.

The simulator also recorded the hard left-hand bank once past Penang and the long, steady line towards Antarctica. There was one distinct difference, though, between this simulated flight and many others Zaharie had in his computer. The others had him landing at a destination and safely debarking. This simulation did not.

There’s a reasonable case to be made that Captain Zaharie deliberately planned and carried out his own death and that of 238 innocent people. One big question is how he was able to quickly incapacitate First Officer Fariq, his cabin crew and all the passengers who had access to mobile communication devices. The easy answer is Zaharie sent Fariq out of the cockpit, locked it, then put on his oxygen mask and instantly depressurized the plane.

The theory carries that Zaharie cut the electrical runs and accelerated the aircraft, immediately climbing to 40,000 feet where his panicky occupants would be overcome by a lack of air. In the mass confusion and commotion, it’s unlikely anyone would have thought to make an outside call. At 40,000 feet, the emergency oxygen masks—the yellow cups hanging from the ceiling—would have been useless. Everyone on board that plane would be dead within minutes. Except for Captain Zaharie.

He would be perfectly fine breathing his cockpit reserve air until he was able to descend the plane back to 30,000 feet and re-pressurize the system. He made precise turns to avoid detection and, once off primary radar, he likely re-energized the plane’s electrical runs which set off the SDU’s automatic reboot. Zaharie might not have even known that Inmarsat was following him.

At what time Captain Zaharie’s life was over, we’ll likely never know. Perhaps he stayed awake and enjoyed the long and steady ride toward his doom in the Indian Ocean. It’s almost unfathomable to envision a lone pilot commanding a plane full of death but, then, it’s almost unfathomable to believe this really happened. As for motive—why Zaharie would’ve done this—it’s truly incomprehensible.

It the “Captain-Did-It” theory is wrong, then this is a tragic accident of unprecedented proportion with no plausible reason. If the theory is right, undoubtedly the missing Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 is a mass murder.

A fascinating read Garry, thanks for sharing it. It’s a sad story indeed. We leave Vietnam tomorrow, flying over the South China Sea towards home. I’m not sure I should have read this story tonight, lol

Take care

Maybe check out your captain before boarding, Linda. 🙂

Garry, I did not see it in your story, but isn’t Penang Island where the captain was from? Of course the naysayers to the captain theory say it was a lithium battery or some electrical problem that caused the mishap. However, I see too many “coincidences” in all this to just be a string of bad luck. I think the turn over Penang Island clinches it for me.

Now that is an interesting observation, Bill. Very interesting, and I’ll look into the significance.

Fascinating to read the account of the flight Garry.

Thanks, June. I first published this four years ago – nothing has changed and I doubt they’ll find the main wreckage anytime soon – maybe upon some future technological advancement. They did find the Titanic, after all. 🙂