There are only three significant questions left unanswered in the assassination of United States President John F. Kennedy which occurred in Dallas, Texas, on November 22nd, 1963.

There are only three significant questions left unanswered in the assassination of United States President John F. Kennedy which occurred in Dallas, Texas, on November 22nd, 1963.

First is Lee Harvey Oswald’s motive.

Why’d he do it? We’ll never know for sure because Oswald never confessed and he died two days later, taking that secret to his grave.

Second – where was Oswald going after the assassination?

He left the scene, went home, grabbed his revolver, and was walking south on a Dallas street when intercepted by Officer JD Tippit. Oswald shot Tippit and continued fleeing before getting cornered in a theatre where he attempted to shoot the arresting officers. Clearly he was planning to live another day.

He left the scene, went home, grabbed his revolver, and was walking south on a Dallas street when intercepted by Officer JD Tippit. Oswald shot Tippit and continued fleeing before getting cornered in a theatre where he attempted to shoot the arresting officers. Clearly he was planning to live another day.

The third question – what happened to the missing bullet?

This can now be reasonably explained, although it’s taken a half century to figure it out.

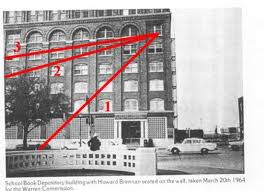

Evidence clearly shows that Lee Harvey Oswald fired three shots from his 6.5 mm Mannlicher-Carcano rifle which was recovered from the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository. Conspiracy theorists – give it a rest. Oswald was the trigger man and he acted alone. Not one single piece of evidence exists to refute this because non-events leave no evidence. It never happened any other way than Oswald acting alone.

Evidence clearly shows that Lee Harvey Oswald fired three shots from his 6.5 mm Mannlicher-Carcano rifle which was recovered from the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository. Conspiracy theorists – give it a rest. Oswald was the trigger man and he acted alone. Not one single piece of evidence exists to refute this because non-events leave no evidence. It never happened any other way than Oswald acting alone.

The problem with the three shot evidence is that only two bullets were recovered. One has never been accounted for.

So what happened to it?

Let’s look at the firearms evidence in the JFK homicide case.

First of all, you have to weigh the ear-witness reports. The vast majority of witnesses stated that three gunshots were heard. Some claimed that one, two, and as many as nine shots were heard, but you’re going to get that variation with the hundreds of people that were present in Dealey Plaza when Kennedy was shot.

You’ve got to give credibility to the witnesses who were closest to the muzzle. There were three Texas School Book Depository workers directly below the sixth floor, southeast window (sniper’s nest) where Oswald fired from. They were unshakable and unanimous that three shots rang out.

You’ve got to give credibility to the witnesses who were closest to the muzzle. There were three Texas School Book Depository workers directly below the sixth floor, southeast window (sniper’s nest) where Oswald fired from. They were unshakable and unanimous that three shots rang out.

Their testimony is corroborated (backed-up) by the fact that three expended shell casings were found in the snipers nest. These three casings were forensically matched as being fired from Oswald’s Carcano ‘to the exclusion of all other firearms’ as the categorical term goes.

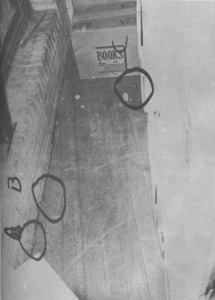

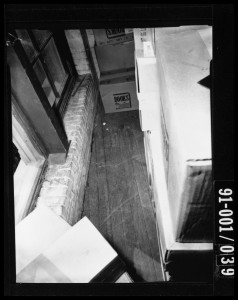

What’s clearly telling is the location in which these casings were found and photographed. In all my reading and research, I can’t find any official comment on the meaning of the casing pattern, although it’s obvious when you simply think about it. Two casings are grouped together, and the third is by itself about five feet from where Oswald pulled his trigger.

What’s clearly telling is the location in which these casings were found and photographed. In all my reading and research, I can’t find any official comment on the meaning of the casing pattern, although it’s obvious when you simply think about it. Two casings are grouped together, and the third is by itself about five feet from where Oswald pulled his trigger.

To further understand the significance, you have to know that Oswald piled a small fortress of book boxes around the sniper’s nest to conceal himself, creating a cardboard wall. When he ejected the casings from his bolt action rifle, they flew through the air at a 90 degree angle from the barrel and struck the wall of boxes to Oswald’s right, then ricocheted to rest on the floor.

To further understand the significance, you have to know that Oswald piled a small fortress of book boxes around the sniper’s nest to conceal himself, creating a cardboard wall. When he ejected the casings from his bolt action rifle, they flew through the air at a 90 degree angle from the barrel and struck the wall of boxes to Oswald’s right, then ricocheted to rest on the floor.

Hmmm… two were together and one was off by itself. It’s obvious that Oswald’s barrel position changed between the lone cartridge and the group of two.

So how does this explain the missing bullet?

Let’s look at the two shots that were accounted for.

The first bullet that hit Kennedy, known in assassination terminology as The Single Bullet Theory, got him through the back of the shoulder/ base of the neck, exited his throat, then entered Texas Governor John Connally’s back. In a rapidly diminishing velocity, it traversed Connally’s chest, blew out below his right nipple, continued on to smash his wrist, and lodge in Connally’s thigh. It remained intact, as full metal jacket bullets are designed to do when they penetrate soft mediums like cloth and flesh, and was recovered on Connally’s stretcher at Parkland Hospital. This bullet is also known as The Magic Bullet.

The first bullet that hit Kennedy, known in assassination terminology as The Single Bullet Theory, got him through the back of the shoulder/ base of the neck, exited his throat, then entered Texas Governor John Connally’s back. In a rapidly diminishing velocity, it traversed Connally’s chest, blew out below his right nipple, continued on to smash his wrist, and lodge in Connally’s thigh. It remained intact, as full metal jacket bullets are designed to do when they penetrate soft mediums like cloth and flesh, and was recovered on Connally’s stretcher at Parkland Hospital. This bullet is also known as The Magic Bullet.

The second bullet that hit Kennedy blasted his head apart. It fragmented into multiple pieces, as full metal jackets are designed to do when they hit a hard medium like bone at a high velocity. Less than fifty percent of this round was recovered. By the way, both of these bullets were ballistically linked to being fired from Oswald’s Carcano ‘to the exclusion of all other firearms’.

The second bullet that hit Kennedy blasted his head apart. It fragmented into multiple pieces, as full metal jackets are designed to do when they hit a hard medium like bone at a high velocity. Less than fifty percent of this round was recovered. By the way, both of these bullets were ballistically linked to being fired from Oswald’s Carcano ‘to the exclusion of all other firearms’.

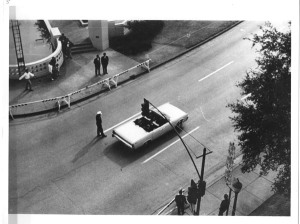

These two shots were recorded on the famous Zapruder film which shows them occurring 4.88 seconds apart with both trajectories in the same line to the sniper’s nest window.

Ergo. The two tightly grouped casings came from these two shots because the angle of ejection, ricochet, and rest pattern are similar.

So why was the third casing so far apart?

Simple. It was fired from a different angle.

Let’s think this thing out, then look at some more physical and witness evidence.

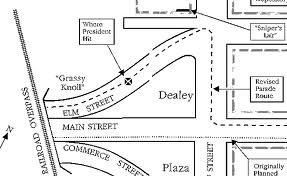

If you were Oswald, intent on shooting the President, would you expose yourself to the eyes-front approach of the motorcade as it approached you from the south on Houston St.? (Remember, Oswald was unstable, but he was calculating.) An approaching target, when you’re in a vertical vantage point, is a tough target to hit (Remember, I was a sniper so I know what I’m talking about). It’s common sense that he’d wait until JFK’s limo rounded the corner onto Elm St. and was nearly stopped right in front of him. That’s the most logical time to squeeze-off a shot.

If you were Oswald, intent on shooting the President, would you expose yourself to the eyes-front approach of the motorcade as it approached you from the south on Houston St.? (Remember, Oswald was unstable, but he was calculating.) An approaching target, when you’re in a vertical vantage point, is a tough target to hit (Remember, I was a sniper so I know what I’m talking about). It’s common sense that he’d wait until JFK’s limo rounded the corner onto Elm St. and was nearly stopped right in front of him. That’s the most logical time to squeeze-off a shot.

But the two shots that killed JFK happened when the limo was far west of the sniper’s nest and vanishing from Oswald’s sight picture.

So why didn’t he fire when he had the closest opportunity?

Well, he probably did.

The angle of ejection for the lone casing is entirely consistent with Oswald firing it at the first logical opportunity which was when the limo was closest to him and the security eyes were facing away.

So how did he miss?

Simple again. As Oswald was following Kennedy in his cross-hairs, a traffic light came into play. Oswald squeezed off the first round, but it hit the metal housing on the light and fragmented.

Simple again. As Oswald was following Kennedy in his cross-hairs, a traffic light came into play. Oswald squeezed off the first round, but it hit the metal housing on the light and fragmented.

This accounts for other evidence like where James Tague, a bystander five hundred and twenty feet to the west, was hit in the cheek by a piece of concrete curb that was sent flying by a lead fragment and where Virgie Rachley stated to have seen sparks fly from the pavement behind the limo when the first of three shots were fired. The simplest explanation is that these fragments were from the first, and missing, bullet.

This accounts for other evidence like where James Tague, a bystander five hundred and twenty feet to the west, was hit in the cheek by a piece of concrete curb that was sent flying by a lead fragment and where Virgie Rachley stated to have seen sparks fly from the pavement behind the limo when the first of three shots were fired. The simplest explanation is that these fragments were from the first, and missing, bullet.