One hundred years ago, on August 2nd, 1923, Warren G. Harding, the 29th President of the United States, suddenly died in a San Francisco hotel room. He was 57 years old. Immediately—due to no autopsy insisted upon by the ironclad demand from his wife, Florence Harding, and the fact that his body was embalmed one hour after death—suspicious rumors of foul play circulated. Conspirators came in many forms. Corrupt politicians, scandal cover-ups, quack physicians, and foreign operatives. But the most sinister accusation of all was Harding being intentionally poisoned by his wife.

One hundred years ago, on August 2nd, 1923, Warren G. Harding, the 29th President of the United States, suddenly died in a San Francisco hotel room. He was 57 years old. Immediately—due to no autopsy insisted upon by the ironclad demand from his wife, Florence Harding, and the fact that his body was embalmed one hour after death—suspicious rumors of foul play circulated. Conspirators came in many forms. Corrupt politicians, scandal cover-ups, quack physicians, and foreign operatives. But the most sinister accusation of all was Harding being intentionally poisoned by his wife.

The official cause of death released in press statements by the attending doctors was a “probable cerebral apoplexy”. In other words, President Harding had a stroke, a fatal brain event. There was no mention of any toxicity through poison nor any suggestion of a chronic cardiac condition, a heart attack.

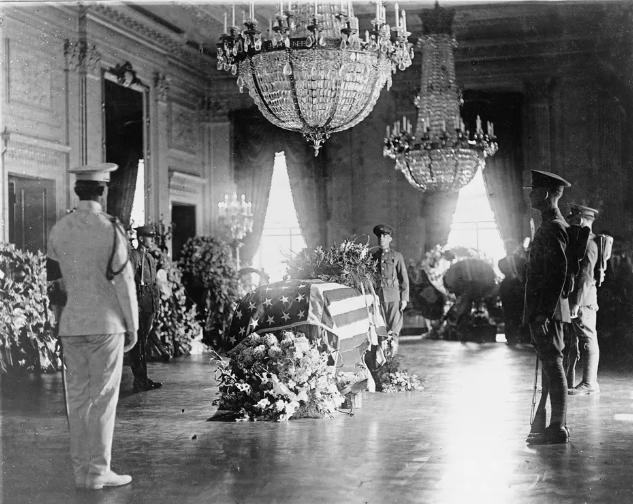

Harding’s body was returned by train to Washington, DC, lay in state for two days, then was transported again by train to his hometown of Marion, Ohio where he was entombed in a marble crypt. His wife, Florence, died the following year of kidney failure and came to rest beside him. As the years passed, the truth of the Harding Administration emerged. It became known as America’s most scandalous presidency.

Extramarital lovers, illegitimate children, political corruption, cronies, bribes, payoffs, and even suicides emerged that painted a black mark on Harding’s history. The persistent suspicion of cover-up in his death failed to go away. Today, there’s a consensus as to what really happened in Harding’s death. We’ll get to that conclusion but, first, let’s look at who Warren Harding was, how he got to the White House, and how he came to die in that San Francisco hotel room.

Warren Gamaliel Harding was born on November 3rd, 1865—the year the Civil War ended—on his grandfather’s farm near Blooming Grove, Ohio. His father was a small-town physician with a small practice that earned little money. His mother was a devoutly religious homemaker with eight children to care for, including Warren who was the oldest. Harding was an average student but a very strong boy with even stronger work ethic.

Following grade school, Harding attended Ohio Central College graduating in 1882 with a B.S. degree (which grounded him as a later politician). Here he gained experience editing and publishing the college paper. After college, Harding worked at various jobs such as a barn painter, a railroad laborer, and a horse team driver. It was in Marion, Ohio where Warren Harding got his first business break.

Harding had saved enough money to purchase a failing newspaper in Marion. He parlayed it into a profitable venture in which he wore all hats—reporter, editor, and publisher. These roles allowed Harding to get well connected and form the “Marion Gang” whom he nepotistically took with him through his political career, including placing some of these friends and allies in high-ranking service jobs in the United States federal government. That was to come back and haunt him.

In the late 1880s, Warren Harding met Florence Kling at a community dance. He became smitten with Florence who was the daughter of a banker and Marion’s richest man. Amos Kling did not approve of Warren Harding and warned Florence that Harding “would never amount to anything”. He refused to speak to Harding.

Florence Harding went to work in their newspaper business. She also got active in his political ambitions. “The only things I know are publishing and politics,” Florence was quoted as saying. She was especially good at politics.

History—now one hundred years after Harding’s death—records Harding to be an excellent speaker, very personable with a great memory for people, a driven man, but not too bright. Florence was smart, and she used her intelligence to make connections and pave roads for Harding to travel as he moved up the Ohio political ladder.

History—now one hundred years after Harding’s death—records Harding to be an excellent speaker, very personable with a great memory for people, a driven man, but not too bright. Florence was smart, and she used her intelligence to make connections and pave roads for Harding to travel as he moved up the Ohio political ladder.

Warren Harding served as an Ohio State Senator from 1900 to 1904. From then to 1906 he was the Lieutenant Governor of Ohio, and in 1910 he ran as Ohio’s Governor but was defeated. Harding went back to the paper industry but in 1915 he entered federal politics and won a seat as a Senator for the State of Ohio. This opened doors in Washington.

The Republican national convention was deadlocked in the 1920 presidential selection race. Ultimately, the delegates chose Warren Harding as a compromise candidate. He went on to represent the Republicans as a moderate in the November 1920 presidential election. Together with running mate Calvin Coolidge, they won a landslide victory over the Democrats.

Warren G. Harding was inaugurated as the 29th United States President on March 4th, 1921. He ran on the slogan “Return to Normalcy” which fit his leadership style. America was only two years past the end of WWI and the public longed for a return to pre-war normal. The country was in a financial recession with what many Americans thought was unnecessary ties still with foreign countries.

Harding focused on a protectionist America by lowering taxes, increasing foreign tariffs, and getting the country out of the League of Nations process that dynamited Woodrow Wilson’s presidency. In one year after taking off, the country rebounded and began prosperity never seen before. It was the Roaring Twenties.

Warren Harding was a hands-off president. He appointed people he thought he could trust into high office and let them loose to do their jobs. His error was not holding them accountable and, given human nature, even his closest friends began to abuse their positions for personal gain.

Harding’s other error—his vice and weakness—was womanizing, drinking, and gambling. Rumors put him having secret tunnels under the White House where he would smuggle his girls in and ply them with illegal alcohol. (Remember, this era was the start of Prohibition.) Harding’s poker games were legendary as well as a well-known fact that he supported mistresses and had at least one illegitimate daughter. Warren and Florence were childless.

Among the brewing political and criminal crises was what’s known as the Teapot Dome Scandal. This involved an oil-producing region in Wyoming that held reserves set apart for the U.S. Navy. Harding had appointed his close Marion Gang friend, Albert B. Fall, as Secretary of the Interior who oversaw the federal lands at Teapot Dome and had the power to award oil production contracts. Fall pocketed hundreds of thousands of payoff money for preferential treatment. This scandal (among others), which Harding knew about, had the potential to have President Harding impeached.

It was under this stressful black cloud that Warren Harding departed Washington on his “Voyage of Understanding” cross-country train and ship tour in June of 1923. Members of Harding’s staff observed his health rapidly deteriorating. A once vibrant man with the world’s best handshake was notably nervous and privately conferring with advisors about how to diffuse the runaway in the Marion Gang.

“I can take care of my enemies all right. But my damn friends… they’re the ones that keep me walking the floor at night,” Harding said to one aide. To another, “If you knew of a great scandal in our administration, would you for the good of the country and the party expose it publicly, or would you bury it?”

President Harding’s tour took him across the west and up to Alaska. He spoke before hundreds of thousands of common folks in places like St. Louis, Kansas City, Denver, Salt Lake City, Helena, and Spokane. He went to a small Alaskan village called Metlakatla, then did a by-stop in Vancouver, Canada before heading straight for San Francisco and checking into the Palace Hotel with an extensive entourage including the future president Herbert Hoover who was his Secretary of Commerce.

Harding’s health had been going downhill since leaving Washington. The stress of his job and unfolding issues gave him a malady then diagnosed as neurasthenia which is an overly nervous condition where the sufferer is unable to relax. Compounding this condition, including non-recognizing many presenting symptoms of bad physical health, was the president’s personal doctor.

Charles E. Sawyer was part of the Ohio Gang. Sawyer wasn’t a trained physician. He was an odd, self-taught homeopath who prescribed plants and birds and rocks and things (not sure about sand and hills and rings) as substitutes for accepted medical practices. But Sawyer was a likable, down-homey Oh-Hi-Yo officially forehead-stamp-approved by Mrs. Harding who saw Sawyer as a 1920s genuine guru teaching them a better way.

Harding also traveled with a real doctor—Joel T. Boone. Dr. Boone knew Harding was critically ill and telegrammed ahead from Alaska to San Francisco, having two of the country’s leading cardiology specialists standing by. These were Dr. Ray Lyman Wilbur, the president of the American Medical Society, and Dr. Charles Cooper, the leading cardiac surgeon in the USA.

Dr. Boone knew what was happening. President Harding was presenting these symptoms:

- Severe abdominal and thoracic pains as in a crushing weight on the chest

- Pain radiating down both arms

- Shortness of breath

- Dyspnoea at night

- Nausea

- Severe bouts of indigestion

- Off and on fever—chills & sweats

- Exhaustion after little energetic effort

- Foul acetonic breath

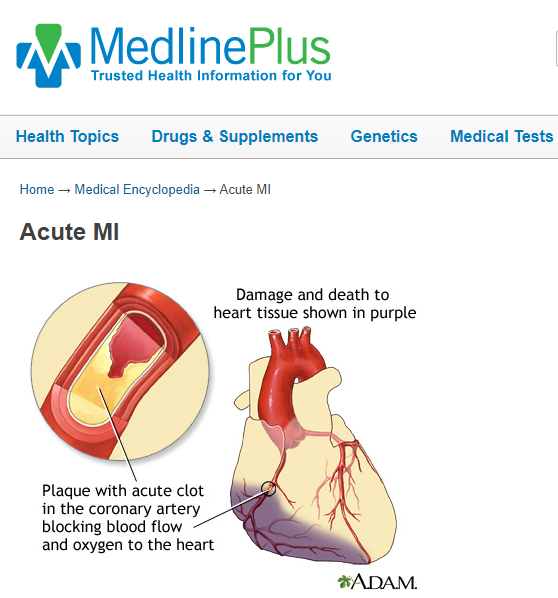

Dr. Boone knew President Harding was suffering congestive heart failure and likely experienced a series of myocardial infarctions where his enlarged heart muscles were quickly failing. Boone knew Harding’s heart was likely to stop, and that he would suddenly die.

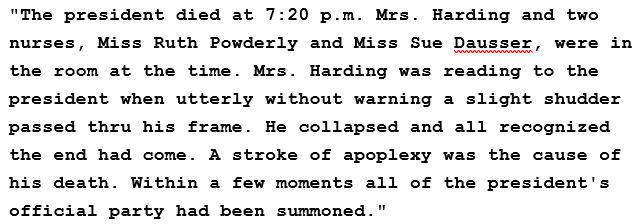

That happened at 7:20 pm on August 2nd, 1923. President Harding was in his hotel suite with his wife and two nurse care aids. Florence was reading a favorable column in the Saturday Evening Post. Harding remarked, “That is good. Go on.”

Florence continued when, with only a shudder and not a sound, the President of the United States stiffened, laid back on the bed, and instantly died.

President Harding’s staff came into the room. That included Herbert Hoover and Doctors Sawyer, Boone, Wilbur, Cooper, and another cardiac expert, Hubert Work. These medical practitioners debated the primary cause of death.

They knew the American public would immediately want to know what happened to their Commander-in-Chief and be assured nothing illegal, conspirator, or dark was behind the president’s sudden and unexpected death—especially when the official reports released to the following press during the Voyage of Understanding assured that Warren Harding was a man fit to competently hold office and guide the nation.

The doctors knew, under the circumstances, that no conclusive cause of death could be established without a complete and thorough autopsy. To this, Florence Harding was fiercely opposed. As Doctor Wilbur put it in his notes written the next day, “We shall never know exactly the immediate cause of President Harding’s death since every effort that was made to secure an autopsy was met with complete and final refusal by Mrs. Harding.”

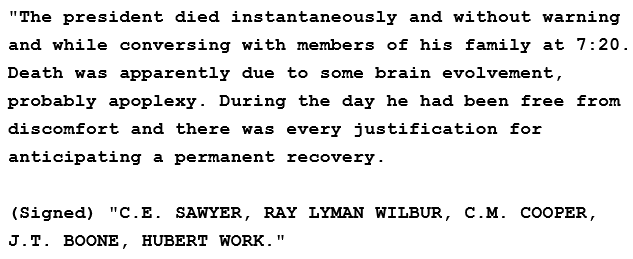

Knowing that the public must be notified of the president’s death as soon as possible and that they would demand to know what happened—what the true cause of death was—the team of five physicians signed this statement:

Realizing their rush to judgment without medical evidence (and strongly suspecting a myocardial infarction or a heart attack), they released this second statement twenty minutes later:

Stroke of Cerebral Apoplexy. Myocardial Infarction. Let’s look at what these medical terms mean.

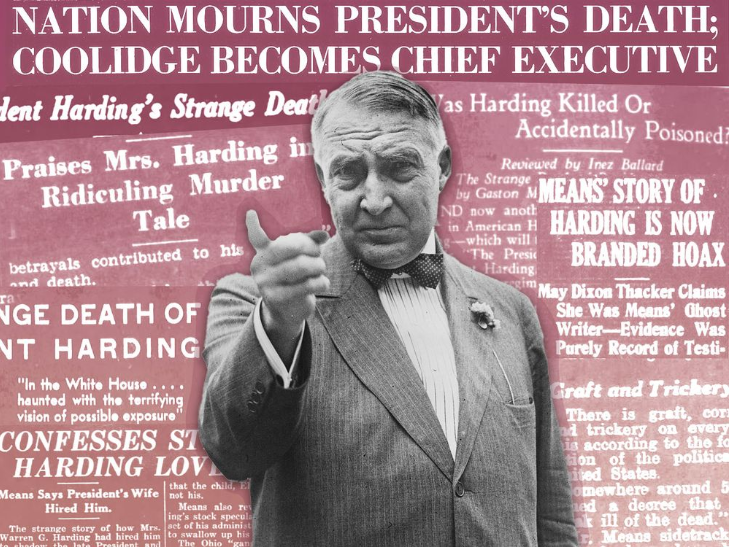

So how did the 1923 American public and folks over the last one hundred years go from accepting that President Warren G. Harding died of natural causes to a conspirator suspicion that he was murdered—possibly by his wife?

I think a few reasons. One is the president’s staff poorly handled the president’s health information. One day the president was strong as an ox. The next day he died.

There was no autopsy. His body was embalmed an hour after death. And this was through an ironclad order from the wife, Florence Harding, who knew full well of her husband’s infidelity and unwinding scandals.

Note: I cannot find anything in historical notes to determine if there was a San Francisco coroner having jurisdiction and the authority to hold the body while an independent autopsy was done. Or if any other authorities like the SF police were notified.

The other factor was the collective doctors’ stick handling of the “probable cause of death.” They were aware of the public backlash for knowing how serious the president’s medical condition and the perception of them not being seen to do something about it and prevent his death, but they first wrote it off as an unpredictable and unpreventable stroke, not a preventable heart attack. From Dr. Wilbur’s notes:

“In the aftermath, we were belabored and attacked by the newspapers antagonistic to Harding, and by the cranks, quacks, antivisectionalists, nature healers, the Dr. Albert Abrams electronic-diagnostic group, and many others. We were accused of starving the president, overfeeding him to death, of assisting in slowly poisoning him, and plying him to death with pills and purgatives. We were accused of being abysmally ignorant, stupid and incompetent, and even of malpractice. We were said to have forced our way to Harding’s bedside “through political pull and for political reasons.”

But the craziest theory of them all came from a book written by Gaston B. Means in 1930 titled The Strange Death of President Harding. Means claimed that Florence Harding murdered her presidential husband with poison. Without a shred of evidence, Means suggested two motives. One was because of her husband’s cheating. The other was to save him the embarrassment of the scandals. Gaston Means, by the way, went to jail over a con job in scamming the Charles Lindberg baby homicide case.

One hundred years have passed since United States President Warren G. Harding passed. There’s no doubt Harding had a fatal heart attack. That’s life, but the fallout from living the presidential life sucks. Here are lines from Herbert Hoover while dedicating a memorial to President Harding:

We saw him gradually weaken not only from physical exhaustion but from mental anxiety. Warren Harding had a dim realization that he had been betrayed by a few of the men whom he trusted, by men whom he believed were his devoted friends. That was the tragedy of the life of Warren Harding.

Hi Garry,

You were able to capture the life, times, and death of Warren Harding in such a succinct – but thorough -piece of writing. While growing up in Marion, I remember hearing several “inside” stories about the president and his clandestine poker games as well as his encounters with Amos Kling. You managed to capture the highs and lows of a man who obviously put too much faith in what his mistakenly believed was friendship. Thanks!

Thanks, Tom. While researching this piece, I got the impression that Warren Harding was a fairly decent man, notwithstanding his affairs, but he generally sought to America a sound place. I appreciate your comment!

Very interesting tale about President Harding. Two minor errors though: The Secretary was Albert Fall, not Fail, and he died at the Palace Hotel, not Place Hotel. As a doctor myself, it does sound as if he had unstable angina with resultant myocardial infarction. Today he would most likely have had a cardiac stent placed or undergone cardiac bypass surgery.

Thanks for the typo corrections, Dr. Granger. It goes to show that one can’t totally depend on AI as a proofreader 🙂