What is consciousness? What’s in you—a conscious and thinking entity—perceiving and processing information from a myriad of sources to form intelligent images in your mind? You’re consciously reading this piece, which I consciously put together to explore an area of existence that current science really doesn’t know much about, and I think you’re wondering—has anyone explained what being conscious really is?

What is consciousness? What’s in you—a conscious and thinking entity—perceiving and processing information from a myriad of sources to form intelligent images in your mind? You’re consciously reading this piece, which I consciously put together to explore an area of existence that current science really doesn’t know much about, and I think you’re wondering—has anyone explained what being conscious really is?

Scientists seem to understand macro laws explaining the origin of the universe and greater physical parameters governing the cosmos. Recent science advancements into quantum mechanics shed better light on micro laws ruling sub-atomic behavior. But nowhere has anyone seemed to clearly explain what consciousness truly is and why we—as conscious beings—observe all this.

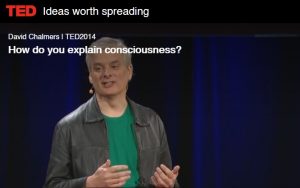

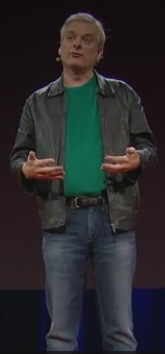

The question of consciousness intrigues me. So much so, that I’ve read, thought and watched a lot on the subject. From what I’ve picked up, one of today’s leading thinkers about consciousness is Dr. David Chalmers. He’s a likable guy with a curious mind and he’s a Professor of Philosophy at New York University. Dr. Chalmers did a fascinating TED Talk called How Do You Explain Consciousness? Here’s the transcript and link to his thought-evoking talk.

Note to readers: It’s worthwhile to listen to Dr. Chalmers TED Talk while reading this transcript.

https://www.ted.com/talks/david_chalmers_how_do_you_explain_consciousness?language=en

Right now, you have a movie playing inside your head. It’s an amazing multi-track movie. It has 3D vision and surround-sound for what you’re seeing and hearing right now, but that’s just the start of it. Your movie has smell and taste and touch. It has a sense of your body, pain, hunger and orgasms. It has emotions, anger and happiness. It has memories like scenes from your childhood playing before you.

Right now, you have a movie playing inside your head. It’s an amazing multi-track movie. It has 3D vision and surround-sound for what you’re seeing and hearing right now, but that’s just the start of it. Your movie has smell and taste and touch. It has a sense of your body, pain, hunger and orgasms. It has emotions, anger and happiness. It has memories like scenes from your childhood playing before you.

And, it has this constant voiceover narrative in your stream of conscious thinking. At the heart of this movie is you. You’re experiencing all this directly. This movie is your stream of consciousness—the subject of experience of the mind and the world.

Consciousness is one of the fundamental facts of human existence. Each of us is conscious. We all have our own inner movie. That’s you and you and you. There’s nothing we know about more directly. At least, I know about my consciousness directly. I can’t be certain that you guys are conscious.

Consciousness also is what makes life worth living. If we weren’t conscious, nothing in our lives would have meaning or value. But at the same time, it’s the most mysterious phenomenon in the universe.

Why are we conscious? Why do we have these inner movies? Why aren’t we just robots who process all this input, produce all that output, without experiencing the inner movie at all? Right now, nobody knows the answers to those questions. I’m going to suggest that to integrate consciousness into science then some radical ideas may be needed.

Some people say a science of consciousness is impossible. Science, by its nature, is objective. Consciousness, by its nature, is subjective. So there can never be a science of consciousness.

For much of the 20th century, that view held sway. Psychologists studied behavior objectively. Neuroscientists studied the brain objectively. And nobody even mentioned consciousness. Even 30 years ago, when TED got started, there was very little scientific work on consciousness.

Now, about 20 years ago, all that began to change. Neuroscientists like Francis Crick and physicists like Roger Penrose said, “Now is the time for science to attack consciousness.” And since then, there’s been a real explosion, a flowering of scientific work on consciousness.

All this work has been wonderful. It’s been great. But it also has some fundamental limitations so far. The centerpiece of the science of consciousness in recent years has been the search for correlations—correlations between certain areas of the brain and certain states of consciousness.

We saw some of this kind of work from Nancy Kanwisher and the wonderful work she presented just a few minutes ago. Now we understand much better, for example, the kinds of brain areas that go along with the conscious experience of seeing faces or of feeling pain or of feeling happy.

But this is still a science of correlations. It’s not a science of explanations. We know that these brain areas go along with certain kinds of conscious experience, but we don’t know why they do. I like to put this by saying that this kind of work from neuroscience is answering some of the questions we want answered about consciousness, the questions about what certain brain areas do and what they correlate with.

But, in a certain sense, those are the easy problems. No knock on the neuroscientists. There are no truly easy problems with consciousness. But it doesn’t address the real mystery at the core of this subject. Why is it that all that physical processing in a brain should be accompanied by consciousness at all? Why is there this inner subjective movie? Right now, we don’t really have a bead on that.

But, in a certain sense, those are the easy problems. No knock on the neuroscientists. There are no truly easy problems with consciousness. But it doesn’t address the real mystery at the core of this subject. Why is it that all that physical processing in a brain should be accompanied by consciousness at all? Why is there this inner subjective movie? Right now, we don’t really have a bead on that.

And you might say, let’s just give neuroscience a few years. It’ll turn out to be another emergent phenomenon like traffic jams, like hurricanes, like life, and we’ll figure it out. The classical cases of emergence are all cases of emergent behavior, how a traffic jam behaves, how a hurricane functions, how a living organism reproduces and adapts and metabolizes, all questions about objective functioning.

You could apply that to the human brain in explaining some of the behaviors and the functions of the human brain as emergent phenomena. How we walk. How we talk. How we play chess—all these questions about behavior.

But when it comes to consciousness, questions about behavior are among the easy problems. When it comes to the hard problem, that’s the question of why is it that all this behavior is accompanied by subjective experience? And here, the standard paradigm of emergence—even the standard paradigms of neuroscience—don’t really, so far, have that much to say.

Now, I’m a scientific materialist at heart. I want a scientific theory of consciousness that works, and for a long time, I banged my head against the wall looking for a theory of consciousness in purely physical terms that would work. But I eventually came to the conclusion that that just didn’t work for systematic reasons.

It’s a long story, but the core idea is just that what you get from purely reductionist explanations in physical terms, in brain-based terms, is stories about the functioning of a system, its structure, its dynamics, the behavior it produces, great for solving the easy problems—how we behave, how we function but when it comes to subjective experience—why does all this feel like something from the inside?

That’s something fundamentally new, and it’s always a further question. So I think we’re at a kind of impasse here. We’ve got this wonderful great chain of explanation that we’re used to it—where physics explains chemistry, chemistry explains biology, biology explains parts of psychology. But consciousness doesn’t seem to fit into this picture.

On the one hand, it’s a datum that we’re conscious. On the other hand, we don’t know how to accommodate it into our scientific view of the world. So I think consciousness right now is a kind of anomaly, one that we need to integrate into our view of the world, but we don’t yet see how. Faced with an anomaly like this, radical ideas may be needed, and I think that we may need one or two ideas that initially seem crazy before we can come to grips with consciousness scientifically.

Now, there are a few candidates for what those crazy ideas might be. My friend Dan Dennett has one. His crazy idea is that there is no hard problem of consciousness. The whole idea of the inner subjective movie involves a kind of illusion or confusion.

Now, there are a few candidates for what those crazy ideas might be. My friend Dan Dennett has one. His crazy idea is that there is no hard problem of consciousness. The whole idea of the inner subjective movie involves a kind of illusion or confusion.

Actually, all we’ve got to do is explain the objective functions, the behaviors of the brain, and then we’ve explained everything that needs to be explained. Well, I say, more power to him. That’s the kind of radical idea that we need to explore if you want to have a purely reductionist brain-based theory of consciousness.

At the same time, for me and for many other people, that view is a bit too close to simply denying the datum of consciousness to be satisfactory. So I go in a different direction. In the time remaining, I want to explore two crazy ideas that I think may have some promise.

The first crazy idea is that consciousness is fundamental. Physicists sometimes take some aspects of the universe as fundamental building blocks: space and time and mass. They postulate fundamental laws governing them, like the laws of gravity or of quantum mechanics. These fundamental properties and laws aren’t explained in terms of anything more basic. Rather, they’re taken as primitive, and you build up the world from there.

Now sometimes, the list of fundamentals expands. In the 19th century, Maxwell figured out that you can’t explain electromagnetic phenomena in terms of the existing fundamentals—space, time, mass, Newton’s laws—so he postulated fundamental laws of electromagnetism and postulated electric charge as a fundamental element that those laws govern. I think that’s the situation we’re in with consciousness.

If you can’t explain consciousness in terms of the existing fundamentals— space, time, mass, charge—then as a matter of logic, you need to expand the list. The natural thing to do is to postulate consciousness itself as something fundamental, a fundamental building block of nature. This doesn’t mean you suddenly can’t do science with it. This opens up the way for you to do science with it.

If you can’t explain consciousness in terms of the existing fundamentals— space, time, mass, charge—then as a matter of logic, you need to expand the list. The natural thing to do is to postulate consciousness itself as something fundamental, a fundamental building block of nature. This doesn’t mean you suddenly can’t do science with it. This opens up the way for you to do science with it.

What we then need is to study the fundamental laws governing consciousness, the laws that connect consciousness to other fundamentals: space, time, mass, physical processes. Physicists sometimes say that we want fundamental laws so simple that we could write them on the front of a t-shirt. Well, I think something like that is the situation we’re in with consciousness. We want to find fundamental laws so simple we could write them on the front of a t-shirt. We don’t know what those laws are yet, but that’s what we’re after.

The second crazy idea is that consciousness might be universal. Every system might have some degree of consciousness. This view is sometimes called panpsychism—pan for all, psych for mind. The view holds that every system is conscious, not just humans, dogs, mice, flies, but even Rob Knight’s microbes, elementary particles. Even a photon has some degree of consciousness.

The idea is not that photons are intelligent or thinking. It’s not that a photon is wracked with angst because it’s thinking, “Aww, I’m always buzzing around near the speed of light. I never get to slow down and smell the roses.” No, it’s not like that. But the thought is maybe photons might have some element of raw, subjective feeling, some primitive precursor to consciousness.

This may sound a bit kooky to you. I mean, why would anyone think such a crazy thing? Some motivation comes from the first crazy idea, that consciousness is fundamental. If it’s fundamental, like space and time and mass, it’s natural to suppose that it might be universal too, the way they are. It’s also worth noting that although the idea seems counterintuitive to us, it’s much less counterintuitive to people from different cultures, where the human mind is seen as much more continuous with nature.

A deeper motivation comes from the idea that perhaps the most simple and powerful way to find fundamental laws connecting consciousness to physical processing is to link consciousness to information. Wherever there’s information processing, there’s consciousness. Complex information processing, like in a human, takes complex consciousness. Simple information processing takes simple consciousness.

A deeper motivation comes from the idea that perhaps the most simple and powerful way to find fundamental laws connecting consciousness to physical processing is to link consciousness to information. Wherever there’s information processing, there’s consciousness. Complex information processing, like in a human, takes complex consciousness. Simple information processing takes simple consciousness.

A really exciting thing is in recent years a neuroscientist, Giulio Tononi, has taken this kind of theory and developed it rigorously with a mathematical theory. He has a mathematical measure of information integration which he calls phi, measuring the amount of information integrated in a system. And he supposes that phi goes along with consciousness.

So in a human brain with an incredibly large amount of information integration it requires a high degree of phi—a whole lot of consciousness. In a mouse with a medium degree of information integration, it still requires a pretty significant, pretty serious amount of consciousness. But as you go down to worms, microbes, particles, the amount of phi falls off. The amount of information integration falls off, but it’s still non-zero.

On Tononi’s theory, there’s still going to be a non-zero degree of consciousness. In effect, he’s proposing a fundamental law of consciousness: high phi, high consciousness. Now, I don’t know if this theory is right, but it’s actually perhaps the leading theory right now in the science of consciousness, and it’s been used to integrate a whole range of scientific data. It does have a nice property that it is, in fact, simple enough that you can write it on the front of a tee-shirt.

Another final motivation is that panpsychism might help us to integrate consciousness into the physical world. Physicists and philosophers have often observed that physics is curiously abstract. It describes the structure of reality using a bunch of equations, but it doesn’t tell us about the reality that underlies it. As Stephen Hawking put it, what puts the fire into the equations?

Well, on the panpsychist view, you can leave the equations of physics as they are, but you can take them to be describing the flux of consciousness. That’s what physics really is ultimately doing—describing the flux of consciousness. On this view, it’s consciousness that puts the fire into the equations. On that view, consciousness doesn’t dangle outside the physical world as some kind of extra. It’s there right at its heart.

I think the panpsychist view has the potential to transfigure our relationship to nature, and it may have some pretty serious social and ethical consequences. Some of these may be counterintuitive. I used to think I shouldn’t eat anything which is conscious, so therefore I should be vegetarian. Now, if you’re a panpsychist and you take that view, you’re going to go very hungry. So I think when you think about it, this tends to transfigure your views, whereas what matters for ethical purposes and moral considerations—not so much the fact of consciousness—but the degree and the complexity of consciousness.

I think the panpsychist view has the potential to transfigure our relationship to nature, and it may have some pretty serious social and ethical consequences. Some of these may be counterintuitive. I used to think I shouldn’t eat anything which is conscious, so therefore I should be vegetarian. Now, if you’re a panpsychist and you take that view, you’re going to go very hungry. So I think when you think about it, this tends to transfigure your views, whereas what matters for ethical purposes and moral considerations—not so much the fact of consciousness—but the degree and the complexity of consciousness.

It’s also natural to ask about consciousness in other systems, like computers. What about the artificially intelligent system in the movie Her, Samantha? Is she conscious? Well, if you take the informational, panpsychist view, she certainly has complicated information processing and integration, so the answer is very likely yes, she is conscious. If that’s right, it raises pretty serious ethical issues about both the ethics of developing intelligent computer systems and the ethics of turning them off.

Finally, you might ask about the consciousness of whole groups, the planet. Does Canada have its own consciousness? Or at a more local level, does an integrated group like the audience at a TED conference—are we right now having a collective TED consciousness, an inner movie for this collective TED group which is distinct from the inner movies of each of our parts? I don’t know the answer to that question, but I think it’s at least one worth taking seriously.

Finally, you might ask about the consciousness of whole groups, the planet. Does Canada have its own consciousness? Or at a more local level, does an integrated group like the audience at a TED conference—are we right now having a collective TED consciousness, an inner movie for this collective TED group which is distinct from the inner movies of each of our parts? I don’t know the answer to that question, but I think it’s at least one worth taking seriously.

Okay, so this panpsychist vision, it is a radical one, and I don’t know that it’s correct. I’m actually more confident about the first crazy idea—that consciousness is fundamental—than about the second one—that it’s universal. I mean, the view raises any number of questions and has any number of challenges, like how do those little bits of consciousness add up to the kind of complex consciousness we know and love.

If we can answer those questions, then I think we’re going to be well on our way to a serious theory of consciousness. If not, well, this is the hardest problem perhaps in science and philosophy. We can’t expect to solve it overnight. But I do think we’re going to figure it out eventually. Understanding consciousness is a real key, I think, both to understanding the universe and to understanding ourselves.