Azaria Chamberlain—a nine-week-old infant—disappeared from her family’s campsite at Ayers Rock (now called Uluru) in the central desert of Australia’s Northern Territory on August 17, 1980. Despite a thorough search and massive investigation, Azaria’s body was never found and the question of whether she was taken from the tent by a dingo (wild dog) or whether she was killed by her mother, Lindy (Lynne) Chamberlain, lingered on.

Azaria Chamberlain—a nine-week-old infant—disappeared from her family’s campsite at Ayers Rock (now called Uluru) in the central desert of Australia’s Northern Territory on August 17, 1980. Despite a thorough search and massive investigation, Azaria’s body was never found and the question of whether she was taken from the tent by a dingo (wild dog) or whether she was killed by her mother, Lindy (Lynne) Chamberlain, lingered on.

Lindy Chamberlain was charged with Azaria’s first-degree murder and convicted of her daughter’s slaying. After thirty-two years, eight legal proceedings, and tens of millions spent in the investigation, Lindy was finally exonerated by a coroner’s inquest that declared Azaria’s death was an accident—the result of a wild animal attack, to wit—a dingo.

The case, which caught world-wide attention, was entirely circumstantial and supported by seemingly incriminating points of forensic evidence that convinced a jury to find Lindy Chamberlain guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. But how credible were these “forensic facts”? Where did the case go wrong? And did a dingo really get her baby?

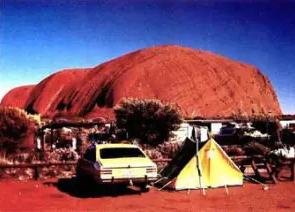

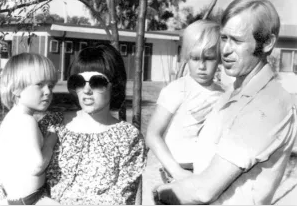

Lindy Chamberlain (34), her husband Michael (38), son Aidan (6), son Reagan (4), and infant Azaria were on a family vacation and pitched their tent in the Ayers Rock public campground at the famous World Heritage site. At 8:00 p.m., and well after dark, Lindy finished breast-feeding Azaria and took her to the tent—thirty feet from the picnic table—where she placed the baby in a bassinet and covered her with blankets. She’d taken Aidan with her to the tent where Reagan was already asleep inside.

Lindy went to their car that was parked beside the tent and got a can of baked beans to give Aidan as a bed-time snack, then returned with Aidan to Michael at the picnic table. At 8:15 p.m. , Azaria cried out. Concerned, Lindy walked toward the darkness of the tent-site and claimed she saw a dingo at the opening of the unzipped tent door. It appeared to have something in its mouth and was violently shaking its head.

Lindy went to their car that was parked beside the tent and got a can of baked beans to give Aidan as a bed-time snack, then returned with Aidan to Michael at the picnic table. At 8:15 p.m. , Azaria cried out. Concerned, Lindy walked toward the darkness of the tent-site and claimed she saw a dingo at the opening of the unzipped tent door. It appeared to have something in its mouth and was violently shaking its head.

Lindy hopped a short parking barricade which made the animal flee into the night. She checked inside the tent. Azaria was gone, and there were fresh blood stains on the floor, bedding, and other articles. Lindy rushed out, yelling to Michael and the other campers, “Help! A dingo’s got my baby!”

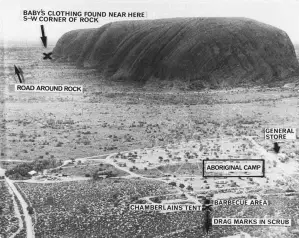

The adjacent campers formed a search party which was re-enforced by authorities and local residents, eventually totaling over three hundred volunteers including Aborigine expert trackers with their dogs. Searchers noted dingo paw prints in the sand outside the tent, and they followed a trail which showed marks indicating a dingo was partly dragging an object, periodically setting it down to possibly rest or readjust its grip. (Azaria weighed just under ten pounds.) The trail indicated its destination was toward known dingo dens at the southwest base of Ayers Rock.

By daylight, they found no sign of the infant, and the search was called off. The Chamberlain family cooperated in a preliminary investigation conducted by police from the nearest town of Alice Springs, then they returned home to Mount Isa.

Initially, no one doubted the Chamberlains’ story. Several campers had seen a dingo in the campground before dark. Others heard a dog growl minutes prior to the baby’s cry. They also heard Lindy’s scream, “A dingo got my baby!” Further, the park ranger had warned that the dingo population was increasing, hungry, and becoming very aggressive. And young Aidan backed up his mother’s story of going to the tent and the car, being with Lindy throughout.

Initially, no one doubted the Chamberlains’ story. Several campers had seen a dingo in the campground before dark. Others heard a dog growl minutes prior to the baby’s cry. They also heard Lindy’s scream, “A dingo got my baby!” Further, the park ranger had warned that the dingo population was increasing, hungry, and becoming very aggressive. And young Aidan backed up his mother’s story of going to the tent and the car, being with Lindy throughout.

The police investigation stopped. But, seven days later, a hiker found some of the garments Azaria was dressed in, nearly three miles away by the dingo dens. The clothes were a snap-buttoned jumpsuit, a singlet, and pieces of plastic diaper, or “nappy” as they say in Australia. Still missing was a “matinee” coat that Azaria wore overtop.

Examiners found bloodstains on the upper part of the jumpsuit which showed a jagged perforation in the left sleeve and a “V”-shaped slice in the right collar. The singlet was inside-out, and the diaper fragments were shredded. The police officer who retrieved the garments failed to photograph their original position as had the original police officers attending the incident failed to photograph the scene. They also failed to properly examine and photo the tent’s interior which others reported was pooled and spotted with blood.

By now, the Dingo’s Got My Baby case was getting international attention and the speculative rumor mill was alive in the media. “Dingos don’t behave like that!” self-appointed experts were saying. “It’s unheard of for a dingo to do this!” “Dingos can’t run with something in their mouths!”

Bigotry was emerging because the Chamberlains were Seventh Day Adventists with Michael being a professional pastor. “They’re a cult!” “They believe in child sacrifice!” “They were at Ayers Rock for a ritual!” “They always dressed the baby in black!” “The name ‘Azaria’ means ‘Sacrifice in the Wilderness’!”

Bigotry was emerging because the Chamberlains were Seventh Day Adventists with Michael being a professional pastor. “They’re a cult!” “They believe in child sacrifice!” “They were at Ayers Rock for a ritual!” “They always dressed the baby in black!” “The name ‘Azaria’ means ‘Sacrifice in the Wilderness’!”

When the first inquest was held in February 1981, the media was in a frenzy and the police were covering their butts. The coroner ruled Azaria’s death was due to a dingo attack, despite there being no physical body to examine. Further, the coroner criticized a shoddy police investigation and certain government officials of the Northern Territory who failed to provide the police with proper resources to investigate.

This threw fuel on the media fire and caused the authorities to start damage control.

A task force was formed to re-open the case, fittingly named Operation Ochre after the red sands of Ayers. It was headed by an ambitious police Superintendent with an aggressive field detective and overseen by a politically protective prosecutor. Collectively, they ran the investigation with the mindset that the dingo attack was implausible, and that Lindy fabricated the story because she’d killed her own kid.

On September 19 1981, Operation Ochre did a massive round-up of the original witnesses for re-interviews and raided the Chamberlains’ home. They seized boxes of items in a search for forensic evidence and impounded their car.

The investigation theory held that Lindy took Azaria from the tent to the car where she slit her baby’s throat, then stuffed her infant’s body in a camera bag. With husband Michael’s help, and after the searchers went home, they took their daughter’s body far away to the dingo dens, buried their little girl, then planted her clothing as a decoy.

The investigation theory held that Lindy took Azaria from the tent to the car where she slit her baby’s throat, then stuffed her infant’s body in a camera bag. With husband Michael’s help, and after the searchers went home, they took their daughter’s body far away to the dingo dens, buried their little girl, then planted her clothing as a decoy.

There wasn’t the slightest suggestion of motive or any consideration of how the Chamberlains were stellar in reputation.

The vehicle was forensically grid-searched over a three-day period by a laboratory technician with a biology background. Suspected bloodstains were found on the console, the floor, and under the dashboard which were described, at trial, as an “arterial spray” pattern.

Blood was also found on various items taken from the Chamberlains’ home that were known to be present in the tent at the time Azaria disappeared. The lab-tech confirmed the blood on Azaria’s jumpsuit was not only human—it was composed of 25 % fetal hemoglobin which was consistent with an infant’s blood.

This was the flawed forensic cornerstone of the prosecution’s circumstantial case.

A second inquest was held in February 1982. It was run as a prosecution—an indictment with the focus on proving a theory, rather than discovering facts. The Chamberlains were not privy to the “evidence” beforehand and had no ability to defend themselves. “Information” was presented by the lab-tech that blood from the car was consistent with fetal hemoglobin and, therefore, the baby must have bled out in the car.

Another forensic expert testified the cuts and bloodstain pattern on the jumpsuit were caused by a sharp-edged weapon, probably a pair of scissors, and were in no way caused by canine teeth.

Another forensic expert testified the cuts and bloodstain pattern on the jumpsuit were caused by a sharp-edged weapon, probably a pair of scissors, and were in no way caused by canine teeth.

Despite all the civilian witnesses testifying consistently as before, and corroborating the Chamberlains claims, the inquest deferred judgment and referred the case to the criminal courts.

Lindy was tried for Azaria’s murder in September 1982, and her husband was accused of being an accessory-after-the-fact. Over a hundred and fifty witnesses testified, many of those being forensic experts—some of considerable note. The Chamberlains were forced to defend themselves, funded by their church and donations by believers in their innocence. They had no access to disclosure of evidence by the prosecution and were kept on the ropes by surprise after surprise of technical evidence which they had no time nor ability to prepare a defense.

This trial was not just sensational in Australia. It was carried by all forms of world news—TV, radio, print, and tabloids. As big as the O.J. Simpson trial would become in America, the Australian public were split on the question of Lindy’s guilt or innocence.

The jury bought the prosecution’s case that science was far more reliable that eye and ear witness testimony and the Chamberlains were convicted. Lindy was sentenced to life imprisonment with hard labor and Michael was given a three-year suspended sentence. A pregnant Lindy went directly to jail where their newest baby—a daughter—was born. Two appeals to Australian high courts fell on deaf ears. They found no fault in the application of law.

The Dingo Got My Baby case never faded from public interest. Many groups petitioned, calling for changes in the law and for a new, fair trial to be held. Pressure mounted on the Australian Northern Territory officials.

On February 02, 1986, a British rock climber fell to his death at Ayers Rock. During the search for his body, Azaria’s missing matinee jacket was found—partially buried in the sand outside a previously unknown dingo den. The examination found matching perforations in the coat consistent with the jumpsuit cuts.

On February 02, 1986, a British rock climber fell to his death at Ayers Rock. During the search for his body, Azaria’s missing matinee jacket was found—partially buried in the sand outside a previously unknown dingo den. The examination found matching perforations in the coat consistent with the jumpsuit cuts.

News of this find caused a massive public outcry against the Northern Territory government, and they reluctantly released Lindy from jail pending a re-investigation. A third inquest was a “paper” review that recommended the matter be sent back to the criminal courts.

A Royal Commission of Inquiry into Lindy Chamberlain’s conviction was held from April 1986 to June 1987. It focused on the validity of the scientific evidence, rather than on legalities of court procedure.

The jewel of the forensic crown—the fetal hemoglobin in the family car bloodstains turned out not to be blood at all. The drops were spilled chocolate milkshake and some copper ore dust while the “arterial spray” was overspray from injected sound deadener applied at the car’s factory.

The clothing cuts became an Achilles’ Heel and toppled the case because the expert witness was, by now, discredited in other cases resulting in wrongful convictions. New forensic witnesses, with more advanced technological expertise, testified the cuts were entirely consistent with being mauled by a dog.

In September 1988, the Australian High Court quashed the Chamberlains’ convictions and awarded them $1.3 million in damages—far less than their legal bills, let alone compensating their pain and suffering. The High Court never said Lindy was innocent, though. It rightfully set aside her conviction but made no amends in publicly proclaiming innocence.

In September 1988, the Australian High Court quashed the Chamberlains’ convictions and awarded them $1.3 million in damages—far less than their legal bills, let alone compensating their pain and suffering. The High Court never said Lindy was innocent, though. It rightfully set aside her conviction but made no amends in publicly proclaiming innocence.

It wasn’t until 2012, that Lindy’s perseverance forced the fourth inquest. The presiding coroner classified Azaria Chamberlain’s death as accidental—being taken and killed by a dingo. Coroner Elizabeth Morris had the decency to publicly apologize to Lindy on behalf of all Australian authorities for a horrific, systematic miscarriage of justice.

Coroner Morris also had the class not to single out individuals. Without her saying, it was evident the police, prosecution, and forensic people instinctively reacted as they’d been trained to react—and that was to individually find evidence to support their case interest and not to follow what didn’t fit.

And Coroner Morris was careful not to burn the media. Lindy’s situation was a media dream, having all the elements of a thrilling novel—mystery, instinctive fears, motherhood, femininity, family, religion, politics, and an exotic location combined with courtroom and forensic drama.

And it came at the expense of an innocent and instinctively-protective human mother whose baby girl got taken by a wild animal—probably a mother dingo instinctively trying to feed and protect her own babies.

And it came at the expense of an innocent and instinctively-protective human mother whose baby girl got taken by a wild animal—probably a mother dingo instinctively trying to feed and protect her own babies.

———

Here are links to more information on the Chamberlain travesty:

Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Azaria Chamberlain’s Death

Lindy Chamberlain–Creighton’s Website

Fascinating and sorrowful story. Glad they had a somewhat happy ending, 30 some years later. I can’t imagine the horrors they experienced due to incompetence, bigotry, and closed minds. Shameful, but all too human.

It’s the most tragic miscarriage of justice I’ve ever heard of. Thanks for commenting, Cecilia.

Funny you chose this case, Garry. Not long ago, I was watching a wildlife documentary featuring dingos. In it, they said if a mother dingo was desperate enough, she would hunt a small human (baby or tiny tot). Apparently, it’s not as rare as one would imagine. I immediately thought of this case. That poor family…

What the Chamberlains experienced is beyond my comprehension, Sue. First to lose a baby in such a violent manner, then to be locked up for it and get dragged through the injustice system for so long. Just horrific. As for the dingo, I can’t blame it for acting on its survival instinct.

What a travesty!

Sounds like it went from Missing Baby to Religious Witch Hunt in less time than it takes to say Didgeridoo!

I find this brand of inescapable ineptitude far more blood chilling than serial killer accounts. *shudder*

Thanks for an interesting (if disturbing) article, Garry!

It’s utterly incomprehensible how this thing escalated, Cyn. I’ve read a fair amount on the Chamberlain case, and I can’t find any reference to the Chamberlains being polygraphed which should have nipped it in the bud. Actually, I don’t think I’ve heard of a graver miscarriage of justice. And I don’t think anyone in authority, involved in the process, was held to account. Sad, sad, sad case of the state destroying a grieving family.

Interesting, never heard of this case. But, it goes to prove, all experts are just experts, who can be wrong.

That is why when I hear the term expert to prove a point, I become suspicious. Who is paying them??

The lack of expertise in this case was appalling. Grossly incompetent. Thanks for dropping by and commenting, Guy!