What is consciousness? What’s in you—a conscious and thinking entity—perceiving and processing information from a myriad of sources to form intelligent images in your mind? You’re consciously reading this piece, which I consciously put together to explore an area of existence that current science really doesn’t know much about, and I think you’re wondering—has anyone explained what being conscious really is?

What is consciousness? What’s in you—a conscious and thinking entity—perceiving and processing information from a myriad of sources to form intelligent images in your mind? You’re consciously reading this piece, which I consciously put together to explore an area of existence that current science really doesn’t know much about, and I think you’re wondering—has anyone explained what being conscious really is?

Scientists seem to understand macro laws explaining the origin of the universe and greater physical parameters governing the cosmos. Recent science advancements into quantum mechanics shed better light on micro laws ruling sub-atomic behavior. But nowhere has anyone seemed to clearly explain what consciousness truly is and why we—as conscious beings—observe all this.

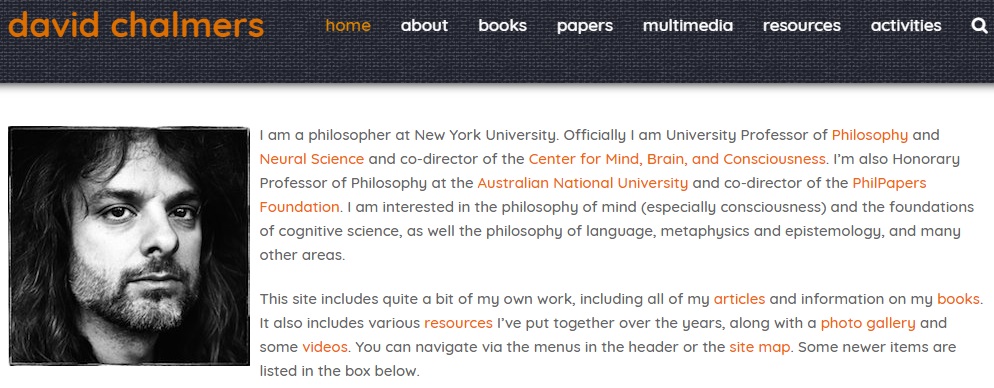

The question of consciousness intrigues me. So much so, that I’ve read, thought and watched a lot on the subject. From what I’ve picked up, one of today’s leading thinkers about consciousness is Dr. David Chalmers. He’s a likable guy with a curious mind and he’s a Professor of Philosophy at New York University. Dr. Chalmers did a fascinating TED Talk called How Do You Explain Consciousness? Here’s the transcript and link to his thought-evoking talk.

Note to readers: It’s worthwhile to listen to Dr. Chalmers TED Talk while reading this transcript.

https://www.ted.com/talks/david_chalmers_how_do_you_explain_consciousness?language=en

Right now, you have a movie playing inside your head. It’s an amazing multi-track movie. It has 3D vision and surround-sound for what you’re seeing and hearing right now, but that’s just the start of it. Your movie has smell and taste and touch. It has a sense of your body, pain, hunger and orgasms. It has emotions, anger and happiness. It has memories like scenes from your childhood playing before you.

Right now, you have a movie playing inside your head. It’s an amazing multi-track movie. It has 3D vision and surround-sound for what you’re seeing and hearing right now, but that’s just the start of it. Your movie has smell and taste and touch. It has a sense of your body, pain, hunger and orgasms. It has emotions, anger and happiness. It has memories like scenes from your childhood playing before you.

And, it has this constant voiceover narrative in your stream of conscious thinking. At the heart of this movie is you. You’re experiencing all this directly. This movie is your stream of consciousness—the subject of experience of the mind and the world.

Consciousness is one of the fundamental facts of human existence. Each of us is conscious. We all have our own inner movie. That’s you and you and you. There’s nothing we know about more directly. At least, I know about my consciousness directly. I can’t be certain that you guys are conscious.

Consciousness also is what makes life worth living. If we weren’t conscious, nothing in our lives would have meaning or value. But at the same time, it’s the most mysterious phenomenon in the universe.

Why are we conscious? Why do we have these inner movies? Why aren’t we just robots who process all this input, produce all that output, without experiencing the inner movie at all? Right now, nobody knows the answers to those questions. I’m going to suggest that to integrate consciousness into science then some radical ideas may be needed.

Some people say a science of consciousness is impossible. Science, by its nature, is objective. Consciousness, by its nature, is subjective. So there can never be a science of consciousness.

For much of the 20th century, that view held sway. Psychologists studied behavior objectively. Neuroscientists studied the brain objectively. And nobody even mentioned consciousness. Even 30 years ago, when TED got started, there was very little scientific work on consciousness.

Now, about 20 years ago, all that began to change. Neuroscientists like Francis Crick and physicists like Roger Penrose said, “Now is the time for science to attack consciousness.” And since then, there’s been a real explosion, a flowering of scientific work on consciousness.

All this work has been wonderful. It’s been great. But it also has some fundamental limitations so far. The centerpiece of the science of consciousness in recent years has been the search for correlations—correlations between certain areas of the brain and certain states of consciousness.

We saw some of this kind of work from Nancy Kanwisher and the wonderful work she presented just a few minutes ago. Now we understand much better, for example, the kinds of brain areas that go along with the conscious experience of seeing faces or of feeling pain or of feeling happy.

But this is still a science of correlations. It’s not a science of explanations. We know that these brain areas go along with certain kinds of conscious experience, but we don’t know why they do. I like to put this by saying that this kind of work from neuroscience is answering some of the questions we want answered about consciousness, the questions about what certain brain areas do and what they correlate with.

But, in a certain sense, those are the easy problems. No knock on the neuroscientists. There are no truly easy problems with consciousness. But it doesn’t address the real mystery at the core of this subject. Why is it that all that physical processing in a brain should be accompanied by consciousness at all? Why is there this inner subjective movie? Right now, we don’t really have a bead on that.

But, in a certain sense, those are the easy problems. No knock on the neuroscientists. There are no truly easy problems with consciousness. But it doesn’t address the real mystery at the core of this subject. Why is it that all that physical processing in a brain should be accompanied by consciousness at all? Why is there this inner subjective movie? Right now, we don’t really have a bead on that.

And you might say, let’s just give neuroscience a few years. It’ll turn out to be another emergent phenomenon like traffic jams, like hurricanes, like life, and we’ll figure it out. The classical cases of emergence are all cases of emergent behavior, how a traffic jam behaves, how a hurricane functions, how a living organism reproduces and adapts and metabolizes, all questions about objective functioning.

You could apply that to the human brain in explaining some of the behaviors and the functions of the human brain as emergent phenomena. How we walk. How we talk. How we play chess—all these questions about behavior.

But when it comes to consciousness, questions about behavior are among the easy problems. When it comes to the hard problem, that’s the question of why is it that all this behavior is accompanied by subjective experience? And here, the standard paradigm of emergence—even the standard paradigms of neuroscience—don’t really, so far, have that much to say.

Now, I’m a scientific materialist at heart. I want a scientific theory of consciousness that works, and for a long time, I banged my head against the wall looking for a theory of consciousness in purely physical terms that would work. But I eventually came to the conclusion that that just didn’t work for systematic reasons.

It’s a long story, but the core idea is just that what you get from purely reductionist explanations in physical terms, in brain-based terms, is stories about the functioning of a system, its structure, its dynamics, the behavior it produces, great for solving the easy problems—how we behave, how we function but when it comes to subjective experience—why does all this feel like something from the inside?

That’s something fundamentally new, and it’s always a further question. So I think we’re at a kind of impasse here. We’ve got this wonderful great chain of explanation that we’re used to it—where physics explains chemistry, chemistry explains biology, biology explains parts of psychology. But consciousness doesn’t seem to fit into this picture.

On the one hand, it’s a datum that we’re conscious. On the other hand, we don’t know how to accommodate it into our scientific view of the world. So I think consciousness right now is a kind of anomaly, one that we need to integrate into our view of the world, but we don’t yet see how. Faced with an anomaly like this, radical ideas may be needed, and I think that we may need one or two ideas that initially seem crazy before we can come to grips with consciousness scientifically.

Now, there are a few candidates for what those crazy ideas might be. My friend Dan Dennett has one. His crazy idea is that there is no hard problem of consciousness. The whole idea of the inner subjective movie involves a kind of illusion or confusion.

Now, there are a few candidates for what those crazy ideas might be. My friend Dan Dennett has one. His crazy idea is that there is no hard problem of consciousness. The whole idea of the inner subjective movie involves a kind of illusion or confusion.

Actually, all we’ve got to do is explain the objective functions, the behaviors of the brain, and then we’ve explained everything that needs to be explained. Well, I say, more power to him. That’s the kind of radical idea that we need to explore if you want to have a purely reductionist brain-based theory of consciousness.

At the same time, for me and for many other people, that view is a bit too close to simply denying the datum of consciousness to be satisfactory. So I go in a different direction. In the time remaining, I want to explore two crazy ideas that I think may have some promise.

The first crazy idea is that consciousness is fundamental. Physicists sometimes take some aspects of the universe as fundamental building blocks: space and time and mass. They postulate fundamental laws governing them, like the laws of gravity or of quantum mechanics. These fundamental properties and laws aren’t explained in terms of anything more basic. Rather, they’re taken as primitive, and you build up the world from there.

Now sometimes, the list of fundamentals expands. In the 19th century, Maxwell figured out that you can’t explain electromagnetic phenomena in terms of the existing fundamentals—space, time, mass, Newton’s laws—so he postulated fundamental laws of electromagnetism and postulated electric charge as a fundamental element that those laws govern. I think that’s the situation we’re in with consciousness.

If you can’t explain consciousness in terms of the existing fundamentals— space, time, mass, charge—then as a matter of logic, you need to expand the list. The natural thing to do is to postulate consciousness itself as something fundamental, a fundamental building block of nature. This doesn’t mean you suddenly can’t do science with it. This opens up the way for you to do science with it.

If you can’t explain consciousness in terms of the existing fundamentals— space, time, mass, charge—then as a matter of logic, you need to expand the list. The natural thing to do is to postulate consciousness itself as something fundamental, a fundamental building block of nature. This doesn’t mean you suddenly can’t do science with it. This opens up the way for you to do science with it.

What we then need is to study the fundamental laws governing consciousness, the laws that connect consciousness to other fundamentals: space, time, mass, physical processes. Physicists sometimes say that we want fundamental laws so simple that we could write them on the front of a t-shirt. Well, I think something like that is the situation we’re in with consciousness. We want to find fundamental laws so simple we could write them on the front of a t-shirt. We don’t know what those laws are yet, but that’s what we’re after.

The second crazy idea is that consciousness might be universal. Every system might have some degree of consciousness. This view is sometimes called panpsychism—pan for all, psych for mind. The view holds that every system is conscious, not just humans, dogs, mice, flies, but even Rob Knight’s microbes, elementary particles. Even a photon has some degree of consciousness.

The idea is not that photons are intelligent or thinking. It’s not that a photon is wracked with angst because it’s thinking, “Aww, I’m always buzzing around near the speed of light. I never get to slow down and smell the roses.” No, it’s not like that. But the thought is maybe photons might have some element of raw, subjective feeling, some primitive precursor to consciousness.

This may sound a bit kooky to you. I mean, why would anyone think such a crazy thing? Some motivation comes from the first crazy idea, that consciousness is fundamental. If it’s fundamental, like space and time and mass, it’s natural to suppose that it might be universal too, the way they are. It’s also worth noting that although the idea seems counterintuitive to us, it’s much less counterintuitive to people from different cultures, where the human mind is seen as much more continuous with nature.

A deeper motivation comes from the idea that perhaps the most simple and powerful way to find fundamental laws connecting consciousness to physical processing is to link consciousness to information. Wherever there’s information processing, there’s consciousness. Complex information processing, like in a human, takes complex consciousness. Simple information processing takes simple consciousness.

A deeper motivation comes from the idea that perhaps the most simple and powerful way to find fundamental laws connecting consciousness to physical processing is to link consciousness to information. Wherever there’s information processing, there’s consciousness. Complex information processing, like in a human, takes complex consciousness. Simple information processing takes simple consciousness.

A really exciting thing is in recent years a neuroscientist, Giulio Tononi, has taken this kind of theory and developed it rigorously with a mathematical theory. He has a mathematical measure of information integration which he calls phi, measuring the amount of information integrated in a system. And he supposes that phi goes along with consciousness.

So in a human brain with an incredibly large amount of information integration it requires a high degree of phi—a whole lot of consciousness. In a mouse with a medium degree of information integration, it still requires a pretty significant, pretty serious amount of consciousness. But as you go down to worms, microbes, particles, the amount of phi falls off. The amount of information integration falls off, but it’s still non-zero.

On Tononi’s theory, there’s still going to be a non-zero degree of consciousness. In effect, he’s proposing a fundamental law of consciousness: high phi, high consciousness. Now, I don’t know if this theory is right, but it’s actually perhaps the leading theory right now in the science of consciousness, and it’s been used to integrate a whole range of scientific data. It does have a nice property that it is, in fact, simple enough that you can write it on the front of a tee-shirt.

Another final motivation is that panpsychism might help us to integrate consciousness into the physical world. Physicists and philosophers have often observed that physics is curiously abstract. It describes the structure of reality using a bunch of equations, but it doesn’t tell us about the reality that underlies it. As Stephen Hawking put it, what puts the fire into the equations?

Well, on the panpsychist view, you can leave the equations of physics as they are, but you can take them to be describing the flux of consciousness. That’s what physics really is ultimately doing—describing the flux of consciousness. On this view, it’s consciousness that puts the fire into the equations. On that view, consciousness doesn’t dangle outside the physical world as some kind of extra. It’s there right at its heart.

I think the panpsychist view has the potential to transfigure our relationship to nature, and it may have some pretty serious social and ethical consequences. Some of these may be counterintuitive. I used to think I shouldn’t eat anything which is conscious, so therefore I should be vegetarian. Now, if you’re a panpsychist and you take that view, you’re going to go very hungry. So I think when you think about it, this tends to transfigure your views, whereas what matters for ethical purposes and moral considerations—not so much the fact of consciousness—but the degree and the complexity of consciousness.

I think the panpsychist view has the potential to transfigure our relationship to nature, and it may have some pretty serious social and ethical consequences. Some of these may be counterintuitive. I used to think I shouldn’t eat anything which is conscious, so therefore I should be vegetarian. Now, if you’re a panpsychist and you take that view, you’re going to go very hungry. So I think when you think about it, this tends to transfigure your views, whereas what matters for ethical purposes and moral considerations—not so much the fact of consciousness—but the degree and the complexity of consciousness.

It’s also natural to ask about consciousness in other systems, like computers. What about the artificially intelligent system in the movie Her, Samantha? Is she conscious? Well, if you take the informational, panpsychist view, she certainly has complicated information processing and integration, so the answer is very likely yes, she is conscious. If that’s right, it raises pretty serious ethical issues about both the ethics of developing intelligent computer systems and the ethics of turning them off.

Finally, you might ask about the consciousness of whole groups, the planet. Does Canada have its own consciousness? Or at a more local level, does an integrated group like the audience at a TED conference—are we right now having a collective TED consciousness, an inner movie for this collective TED group which is distinct from the inner movies of each of our parts? I don’t know the answer to that question, but I think it’s at least one worth taking seriously.

Finally, you might ask about the consciousness of whole groups, the planet. Does Canada have its own consciousness? Or at a more local level, does an integrated group like the audience at a TED conference—are we right now having a collective TED consciousness, an inner movie for this collective TED group which is distinct from the inner movies of each of our parts? I don’t know the answer to that question, but I think it’s at least one worth taking seriously.

Okay, so this panpsychist vision, it is a radical one, and I don’t know that it’s correct. I’m actually more confident about the first crazy idea—that consciousness is fundamental—than about the second one—that it’s universal. I mean, the view raises any number of questions and has any number of challenges, like how do those little bits of consciousness add up to the kind of complex consciousness we know and love.

If we can answer those questions, then I think we’re going to be well on our way to a serious theory of consciousness. If not, well, this is the hardest problem perhaps in science and philosophy. We can’t expect to solve it overnight. But I do think we’re going to figure it out eventually. Understanding consciousness is a real key, I think, both to understanding the universe and to understanding ourselves.

Thank you for this thought-provoking post. I don’t think the hard problem of consciousness will ever be solved. What would an explanation even look like? How could you even put it into words? Perhaps it’s simply beyond human comprehension.

By the way, the neuroscientist Sam Harris did a two-part blog post on his website (samharris.org) called “The Mystery of Consciousness” which (as the title suggests) explores this topic.

And thank you for checking out my posts, Paul. God knows what consciousness is 🙂

I suggest you read, “Many Lifetimes” by Joan Grant and Denys Kelsey.

Thanks, Gloria. I had a quick “Look Inside” at Amazon https://www.amazon.com/Many-Lifetimes-Denys-Kelsey/dp/B000NNGN0K

Do you remember the first thing you ever remembered?

What’s the difference between self awareness and the first thing you ever remembered?

I think consciousness is some kind of pattern matching compare operation involving the playback of a previously recorded section of your continously recorded sensory movie.

Good question about self awareness and consciousness/memory. I think my earliest memory is around 3-4 years old but it also might be influenced by old family photos. Thanks fo reading & commenting, Randy!

This topic is very important to me. I cured myself of what I think is called anthrophophobia (a constant elevated fear of people) from which I had suffered for 42 years. All I know is that last year, after a two week period of applying my therapy and witnessing improvement, I woke up one morning and I wasn’t afraid anymore. It was a strange reality, suddenly I realized I didn’t know who I was. Something very perplexing about my brain was working differently, but I didn’t care about that as much as my astonishment at not feeling terrified. It was gone! I was completely relaxed. And I was awake! I was thrilled!

Since then I’ve discovered that other insecurities, emotional dysfunctionalities, stemming from child abuse caused my own adaptive behavior to trigger my anthropophobia.

The adaptive process occurs in a devastating negative self feedback downward spiral of emotional functionality in the brain.

Our emotions are subconsciously in control of what we will consciously “feel”.

Our inherited emotions are more fundamental, they cannot be altered.

Our learned emotions, shame, guilt are consciously hammered into us by conditioned responce.

Who we are (our consciousness) depends on our memories and their relationship to our emotions.

This topic amazes me too, Garry.

Thank you so much for sharing your experience, Randy. I had to Google anthropophobia as I wasn’t familiar with the term. I can relate to you about phobias as I suffered from glossophobia for years – that’s the fear of public speaking. It’s not really a fear of people. It’s the fear of speaking up in public groups and that can be only as many as three or four. I overcame it (to the most degree) with age and practice but I still worry about butterflies when faced with in-person appearances. It’s funny, though, that I have no nervousness around radio microphones or TV cameras which usually have a much larger audience to screw up in front or rather than just a room full of live faces. Go figger 🙂 Nice to hear your success and thanks so much for commenting!

And who is watching this movie?

My earliest memory is of lying in my crib in the dark as a baby and looking at the doorknob, thinking how strange it looked.

Good question as to who’s watching the movie, Virginia. It might be the real “self”.

“Who” is watching?

A very well stated question that directly addresses an excellent observation (Problem Solving 809 – graduate studies stuff).

I like the way the way you think, Virginia.

“hmm, this begs me to consider the following thought experiment.”

If you had no memory, but were receiving the “now” input of your sensory data stream, could you experience what we call consciousness?

If your sensory input data stream were changing you couldn’t “know” it. Because you wouldn’t have past snapshot images to compare the differences from now, or after, to anything before. The passage of time would be imperceptible.

Hmm, would this thought experiment imply that the ability to “know” anything (whatever “know” is) be necessarily dependent upon some low level continuous derivative (time rate of change) output derived from some sensory input datum as either decreasing, constant or increasing?

My observation is that such a capability would likely require, at minimum, some kind of continuously looping or recursive multiple I/O point data acquisition, processing, storage and retrieval system.

First things first:

Evidently, from an evolutionary viewpoint, the continued living existance of a “specie’s genes” or dna is, by way far, a much more successful naturally occuring biological process, if large numbers of similar, relatively short-lived copies of the specie’s possess the ability and high probability of individually performing the following sequential steps:

1. Adapt/alter it’s copy of dna, subject to the conditions in it’s specific environment.

2. Reproduce the specie’s dna via the mixing of dna sequenced molecules of two different individuals that grow into better adapted next generation copies.

3. The current generation dies off. If the next generation thrives, GoTo step 1.

Many very complex non sentient life forms perform this amazing feat. Plants, for example, do not have to be aware of or learn how to perform photosynthesis, grow roots, leaves, flowers or how to regulate their circulatory systems. Basically, all of a plants life support and reproduction functionality is inherited from its ancestors. But the plant’s ability to survive and reproduce the next generation is at the mercy of it’s environment. It cannot go find fertile soil, run from predators or choose its mate.

Consider the demands upon a brain-toting sentient being. It must have many built-in, automatic, non sentient capabilities, such as heart beat and breathing regulation.

From the survival of the specie’s vantage point (top priority – by far).

A sentient being must:

1. Successfully survive – long enough to find a mate and reproduce.

2. Successfully reproduce – before it dies.

3. Successfully interact socially with other members of the species. (especially man, man is a social creature, we cannot thrive in isolation)

My theory is that the sentient biological brain has evolved, via necessity of efficiency, (and thus has inherited from it’s parents) the ability to automatically (via subconscious instinct) respond, as a correct emotional feeling message, to a majority percentage of the Survival, Reproduction and Social Interaction environmental stimuli that may come across the individual’s sensory input data stream… (an instinctual responce).

Examples:

1) That snake in your peripheral vision was suddenly brought to your attention (subconscious situational awareness) and you feel very scared.

2) You feel very attracted to an individual of the opposite sex.

3) You feel so happy because you were finally selected to play on the basketball team.

…But you didn’t consciously think-up these feelings. They just happend when you became aware of the situation.

You do not have conscious control of your (subconsious) emotions. Your (subconscious) emotions have control of (are) your conscious feelings…

Try to consciously make yourself feel embaressed. You can’t.

But you can make yourself feel embaressment by remembering the time (memory playback of your sensory movie) that you were the most embaressed you have ever been.

Make a conscious decision that you will not become startled and jerk the next time you hear a sudden loud boom.

Doesn’t work.

The inherited, permanent, emotional desire to have sex is second only to the inherited, permanent,

emotional desire to survive. These instinctual emotional feelings are so deeply engrained in our subconscious minds that they cannot be prevented from being felt.

I think that the subconscious mind is in control of about 90% of human behavior… Things like your gut feeling that if you go down that street you will not come back. Or that mate selection is mostly determined subconsciously and that only after mutual qualification do you feel the conscious awareness of sexual attraction (because it’s too important to get wrong, and you are not qualified to make a proper decision). The remaining 10% is under conscious control to allow for successful adaptation to the social culture you are born in and in which your learned emotions are taught (shame responce).

I believe that our emotions are actually a very high level, densly packed, communication language (or communication of information stream with a specific data format) that our brains are pre-wired to recognize (without having to learn – imagine that a picture is worth a thousand words, a movie is worth a thousand pictures and a 3D moving hologram is worth a thousand movies. Bump it up a couple of notches and you get something like what I think emotions are. The language communicates what we call emotions or feelings. It also recognizes and communicates in all five of our sensory input/output data stream formats, primarily via visual eye links and body movements. It’s pretty much universal – It works in cities and night clubs in Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, Philippines and in the US. I think dogs can read it a bit better than they can speak it, cats get some of it but don’t seem to speak it as well as dogs. Who knows what else it can do? Oh and also it can be transfered genetically to our offspring via the dna molecule.

I think our consciousness, the self, that watches, rewinds, recalls and plays back our sensory movie is likely only the necessary minimal absolute decision making capable system, that can make an informed decision like – do I turn left or do I turn right at the next intersection – but only if the lower 90% of our subconsious processing system couldn’t match the input sensory stream data to an appropriate pre-determined response commands.

Consciousness, I think, is at the tip of the iceberg of information transformation processes that start at the continuous recursive I/O data acquisition and processing system I spoke of at the beginning of this post.

Unfortunately 90% of the transformation changes to the input stream are hidden away in inaccessable subconscious operations before the “self” output makes it to top of the iceberg as our consciousness.

That’s an interesting idea. Essentially you are equating life forms with organic computers. Perhaps to some extent they are. However, consider this: although we are often unaware of the streams of data coming in through our sensory system, we may just have tuned them out. We can train ourselves to be more alert/aware. We have all seen people who are seemingly oblivious to everything going on around them, and others who are aware of things that don’t make it past our censors. (Think cops and military). Artists are more aware of nuances of colour and shadow than most people, musicians more aware of subtleties of tone, etc. Part of this may well be innate, but part is learned and disciplined.

Also, although our autonomic nervous systems take care of most of our body functions, we can consciously override it and assume control. (Biofeedback, for example) Tibetan monks can control body functions to a degree we can barely imagine. To me, this indicates consciousness is more than a passive acceptance of inflow. It is a directed outflow to alter what might otherwise inflow, such as burns on feet after walking over coals.

You mentioned a gut feeling if you go down that street you won’t come back alive. Somehow you KNOW. You are aware of some danger there, or some future happening. Because the knowing has no apparent source, you say it is unconscious. I believe that knowing is our normal state. Unfortunately, we rarely attain it, and when we get these flashes of knowing, we tend to discount them. I can tell you from my own experience, any time I have ignored one of these gut feelings, I have regretted it.

Consciousness is like a muscle. If you don’t exercise it, it gets weak and undependable. Do you remember first learning to drive? You were hyper aware of everything around you, had to consciously think about pressing the pedals more firmly or letting up on them, consciously think how much to turn the wheel, etc. After you did it long enough, those behaviours became a pattern you could run automatically, for the most part. You developed a callus over your awareness, to some degree. But you need to be aware of what’s happening all around, and that callus isn’t all that beneficial. That child playing on the lawn may suddenly run in front of your car. You need to be able to anticipate that. Accidents happen because people stop being aware.

The fact that we can focus and direct awareness indicates to me that it’s more than DNA or subconscious I/O. The “I” is manning the door.

Wow. I prefer the second crazy idea, that there’s a universal consciousness in all living matter. Perhaps levels of consciousness, dependent on need. It’s a fascinating subject and an outstanding post. Thanks for sharing, Garry.

I’m with you on the second idea, Sue, and I don’t think it’s all that crazy. It makes sense (at least from the little we know about consciousness) that the more complex the life form, the more advanced its consciousness is. What I’d really like to know is the consciousness level of entities that are far more up the complexity scale than we are 🙂

This is an interesting discussion about a fascinating aspect of our universe. I tend to think of consciousness as fundamental to life. How else could earthworms learn mazes? How could plants know when their fellows are being hurt, or show a preference for certain music? It makes sense that the more advanced a life form is,the more sentient (conscious) it is. But even photons appear to have some form of communication, which implies some form of consciousness. We are so used to thinking of humans as being unique and wonderful that we tend to discount the possibility of consciousness where there doesn’t exist a structure similar to our neural network, synapses and brain.

Or (cue the spooky music) is it possible that because what we experience depends on our consciousness, it only exists because of our consciousness. i.e. we are creating it, moment by moment.? Some people are much more aware than others of certain phenomena. Animals have a keener awareness than we do in certain areas (such as sensing thunderstorms coming). There are also cultural differences in awareness, which indicates that perhaps consciousness is modulated by education.

You might enjoy the writings of Joseph Chilton Pearce. One of my favourite books is his Magical Child.

Studying consciousness is something like looking in a mirror. You don’t see your own face; you see a reflection of it.

Very well articulated, Virginia. You make an excellent point about looking in a mirror and we only see a reflection of our true consciousness. My life experiences suggest that everything in the universe is somehow interconnected and that pure consciousness – infinite intelligence – is likely what we perceive as “God”. I’ll look up Joseph Chilton Pearce – and thanks for your thoughtful comment!

I agree. Philosophers have thought along those lines for thousands of years. In Hindu belief, for example, there is the Atmen. An idea espoused in one of Carlos Castaneda’s books is that the original consciousness (God?) broke itself into pieces so that each piece could have different experiences and when those pieces returned to the whole, the whole was enriched. I haven’t explained that well. It has been many decades since I read his books, so I am going on memory. Although his writings have been debunked as not factual, there is something in them that still speaks to people. He probably should have published them as philosophy rather than anthropology.

One of my interests is quantum physics (if only they had taught this in school!) One of the comments in one of the books I read (unfortunately, I can’t locate the reference atm) went along the lines of “the more we learn about the sub-atomic world, the more it seems the universe is nothing but a giant thought”. It was probably in either The Zen of Physics or The Dancing Wu Li Masters.

I’ll quit rambling now.

You’re not rambling at all, Virginia. I find this stuff fascinating. Back when I wrote No Witnesses To Nothing, I did a lot of research into quantum physics and Shamanism – go figger – I managed to associate them 🙂 and that led me to checking out Castaneda. By then he’d been pretty much debunked but he still has some interesting views. It’s becoming increasingly evident to physicists that the rules are entirely different for the micro as they are for the macro. The search for the Grand Unified Theory continues and somehow it seems consciousness plays a role. You may be right that existence is just one big thought 🙂 BTW, do you follow Napoleon Hill teachings and his views on Infinite Intelligence?

I haven’t been exposed to those yet, but I will definitely look into it.