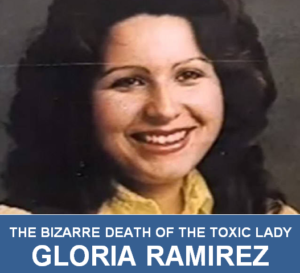

At 8:15 pm on February 9, 1994 paramedics wheeled 31-year-old Gloria Ramirez—semi-conscious—into the Emergency Room at Riverside General Hospital in Moreno Valley, California. Forty-five minutes later, Ramirez was dead and 23 out of the 37 ER staff were ill after being exposed to toxic fumes radiating from Ramirez’s body. Some medical professionals were so sick they required hospitalization. Now, 27 years later, and despite one of the largest forensic investigations in history, no conclusive cause of her toxicity has been identified. Or has there?

At 8:15 pm on February 9, 1994 paramedics wheeled 31-year-old Gloria Ramirez—semi-conscious—into the Emergency Room at Riverside General Hospital in Moreno Valley, California. Forty-five minutes later, Ramirez was dead and 23 out of the 37 ER staff were ill after being exposed to toxic fumes radiating from Ramirez’s body. Some medical professionals were so sick they required hospitalization. Now, 27 years later, and despite one of the largest forensic investigations in history, no conclusive cause of her toxicity has been identified. Or has there?

The Toxic Lady case drew worldwide attention. No one in medical science had experienced this, nor had anyone heard of it. How could a dying woman radiate enough toxin to poison so many people yet leave no pathological trace?

The medical cause of Ramirez’s death was clear, though. She was in Stage 4 cervical cancer, had gone into renal failure, which led to cardiac arrest. Anatomically, the fumes had nothing to do with Gloria Ramirez’s death. But what caused the fumes?

“If the toxic emittance was not a death factor, then what in the world’s going on here?” was the question going on in so many minds—medico, legal, and layperson. To answer that, as best as is possible, it’s necessary to look at the Ramirez case facts both from what the eyewitnesses (and the overcome) said and what forensic science can tell us.

Gloria Ramirez, a wife and mother of two, was in terrible health when she arrived at Riverside Hospital. She’d rapidly deteriorated after being in palliative, home-based care with a diagnosed case of terminal cervical cancer. In the evening of February 9th, Ramirez developed Cheyne-Stokes breathing and went into cardiac arrhythmia or heart palpitations. Both are well-known signs of imminent death. Her home caregivers called an ambulance and had her rushed to the hospital as a last life-saving resort.

Gloria Ramirez, a wife and mother of two, was in terrible health when she arrived at Riverside Hospital. She’d rapidly deteriorated after being in palliative, home-based care with a diagnosed case of terminal cervical cancer. In the evening of February 9th, Ramirez developed Cheyne-Stokes breathing and went into cardiac arrhythmia or heart palpitations. Both are well-known signs of imminent death. Her home caregivers called an ambulance and had her rushed to the hospital as a last life-saving resort.

A terminal cancer patient, like Gloria Ramirez, was nothing new to the Riverside ER team. She was immediately triaged, and time-proven techniques were quickly applied. First, an IV of Ringer’s lactate solution was employed—a standard procedure for stabilizing possible blood and electrolyte deficiencies. Next, the trauma team sedated Ramirez with injections of diazepam, midazolam, and lorazepam. Thirdly, they began applying oxygen with an Amb-bag which forced purified air directly into Ramirez’s lungs rather than hooking up a regular, on-demand oxygen supply.

So far, Ramirez’s case was typical. It wasn’t until an RN, Susan Kane, installed a catheter in Ramirez’s arm to withdraw a syringe of blood that circumstances went from controlled to completely uncontrollable. Kane, a highly experienced RN, immediately noted an ammonia-like odor emanating from the syringe tip when she removed it from the catheter. Kane handed the syringe to Maureen Welch, a respiratory therapist, and then Kane leaned closer to Ramirez to try and trace the unusual odor source.

Welch also sniffed the syringe and later agreed with the ammonia-like smell. “It was like how rancid blood smells when people take chemotherapy treatment,” Welch would say. Welch turned the syringe over to Julie Gorchynski, a medical resident, who noticed manila-colored particles floating in the blood as well as confirming the ammonia odor. Dr. Humberto Ochoa, the ER in-charge, also observed the peculiar particles and gave a fourth opinion that the syringe smelled of ammonia.

Welch also sniffed the syringe and later agreed with the ammonia-like smell. “It was like how rancid blood smells when people take chemotherapy treatment,” Welch would say. Welch turned the syringe over to Julie Gorchynski, a medical resident, who noticed manila-colored particles floating in the blood as well as confirming the ammonia odor. Dr. Humberto Ochoa, the ER in-charge, also observed the peculiar particles and gave a fourth opinion that the syringe smelled of ammonia.

Susan Kane stood up from Ramirez (who was still alive) and felt faint. Kane moved toward the door and promptly passed out—being caught in the nick of time before bouncing her head off the floor. Julie Gorchynski also succumbed. She was put on a gurney and removed just as Maureen Welch presented the same symptoms of being overcome by a noxious substance.

By now, everyone near the dying Gloria Ramirez was feeling the effects. Ochoa, himself now ill, ordered the ER evacuation and for everyone—staff and patients—to muster in the open parking lot where they stripped down to their underclothes and stuffed their outer garments into hazmat bags.

Ramirez remained on an ER stretcher. A secondary trauma team quickly donned hazmat PPE (Personal Protection Equipment) and went back to give Ramirez what little help was left. They did CPR until 8:50 pm when the supervising doctor declared Gloria Ramirez to be dead.

Taking utter precaution, the backup trauma team sealed Gloria Ramirez’s body in multi-layers of body shrouds, sealed it in an aluminum casket, and placed it in an isolated section of the morgue. Then they activated a specially-trained hazmat team to comb the ER for traces of whatever substance had been released and caused such baffling effects to so many people. They found nothing.

Taking utter precaution, the backup trauma team sealed Gloria Ramirez’s body in multi-layers of body shrouds, sealed it in an aluminum casket, and placed it in an isolated section of the morgue. Then they activated a specially-trained hazmat team to comb the ER for traces of whatever substance had been released and caused such baffling effects to so many people. They found nothing.

Meanwhile, Riverside hospital staff had to treat their own. Five workers were hospitalized including Susan Kane, Julie Gorchynski, and Maureen Welch. Gorchynski suffered the worst and spent two weeks detoxifying in the intensive care unit.

The Riverside pathologists faced a daunting and dangerous task—autopsying the body which they considered a canister of nerve gas harboring a fugitive pathogen or toxic chemical. In airtight moon suits, three pathologists performed what might have been the world’s fastest autopsy. Ninety minutes later, they exited a sealed and air-tight examining room with samples of Gloria Ramirez’s blood and tissues along with air from within the shrouds and the sealed aluminum casket.

The autopsy and subsequent toxicology testing found nothing—nothing remotely abnormal that would explain how a routine cancer patient could be so incredibly hostile. The cause of death, the pathologists agreed, was cardiac arrest antecedent (brought on by) to renal (kidney) failure antecedent to Stage 4 cervical cancer. The Riverside coroner concurred, and his mandate was fulfilled with no doubt left about why and how Gloria Ramirez died.

For the coroner, that should have been it. There was no evidence linking the mysterious fumes to the cause of death, and whatever by-product was in the ER air was not a contributor to the decedent’s demise. That problem should have been one for the hospital to figure out on their own. However, the Riverside coroner was under immense public pressure to identify the noxious substance for no other reason than preventing it from happening again.

The coroner worked with the hospital, the health department, the toxicology lab, and Gloria Ramirez’s family to come to some sort of reasonable conclusion. The Ramirez family had no clue—no suspicions whatsoever—of any foreign substance Ramirez had ingested or been exposed to that could trigger such a toxic effect. The toxicology lab was at a wit’s end. They’d never seen a case like this, let alone heard of one. And the health department went off on a tangent.

The county’s health department appointed a two-person team—a team of medical research professionals—to interview every person exposed to the ER and surrounding area on February 9, 1994. They profiled those people so closely that the two-expert team even cross-compared what everyone did, or didn’t, have for dinner that night. When that preeminent probe was over, and no closer to a smoking gun than the struck-out hazmat team failed to find on the night of the fright, the interviewers came to a conclusion—mass hysteria.

The team of two medical doctors, both research scientists, concluded there was no poisonous gas. In their view, in the absence of evidence, there was only one explanation and that was that 23 people simply imagined they were sick. Some, they concluded, had such vivid imaginations that they placed themselves into the intensive care unit.

This was the report the health department delivered to the coroner. While the coroner was now scrambling for damage control, some of the “imaginary” health care workers who could have died during exposure, launched a defamation lawsuit against the hospital, the health department, and the two investigators who concocted the mass hysteria conclusion.

Frustrated with futility, the coroner (who was way outside his jurisdictional boundaries) turned to outside help. He found it at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratories (LLNL) near San Francisco.

Lawrence Livermore initially wasn’t in the medical or toxicological business. They were nuclear weapons makers with a busy mandate back in the cold war era. Now, by the 90s, their usefulness was waning, and so was their funding, so they decided to broaden their horizons by creating the Forensic Science Center at LLNL.

Brian Andresen, the center’s director, took on the Toxic Lady case. The coroner gave Andresen all the biological samples from Ramirez’s autopsy as well as the air-trapping containers. Andresen set about using gas-chromatograph-mass spectrometer (CG-MS) analysis which would have been the same process the Riverside County toxicologist would have used to come up with a “nothing to see here, folks” result.

But Andresen did find something new to see. He found traces dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in Ramirez’s system. Not a lot—just traces—but clearly it was there. Andresen felt he was on to something.

Dimethyl sulfoxide, on its own, is stable and harmless. It’s an organic sulfur compound with the chemical formula (CH3)2S0, and is readily available as a degreasing agent used in automotive cleaning. It’s also commonly ingested and topically applied by a cult-like, self-medicating culture of cancer patients. At one time, there was a clinical trial approved by the FDA to use DMSO as a medicine for pain treatment, and it was dearly adopted by the athletic world as a miracle drug for sports injuries. The FDA abruptly dropped the DMSO program when they realized prolonged use could make people go blind.

Brian Andresen developed a theory—a theory adopted by many scientists who desperately wanted some sort of scientific straw to grasp in explaining the bizarre death of the Toxic Lady—Gloria Ramirez. Andresen’s theory went like this:

Gloria Ramirez had been self-medicating with DMSO. When she went into distress at home, the paramedics placed her in an ambulance and immediately applied oxygen. Ramirez received more oxygen at the ER which started a chemical reaction with the DMSO already in her body systems.

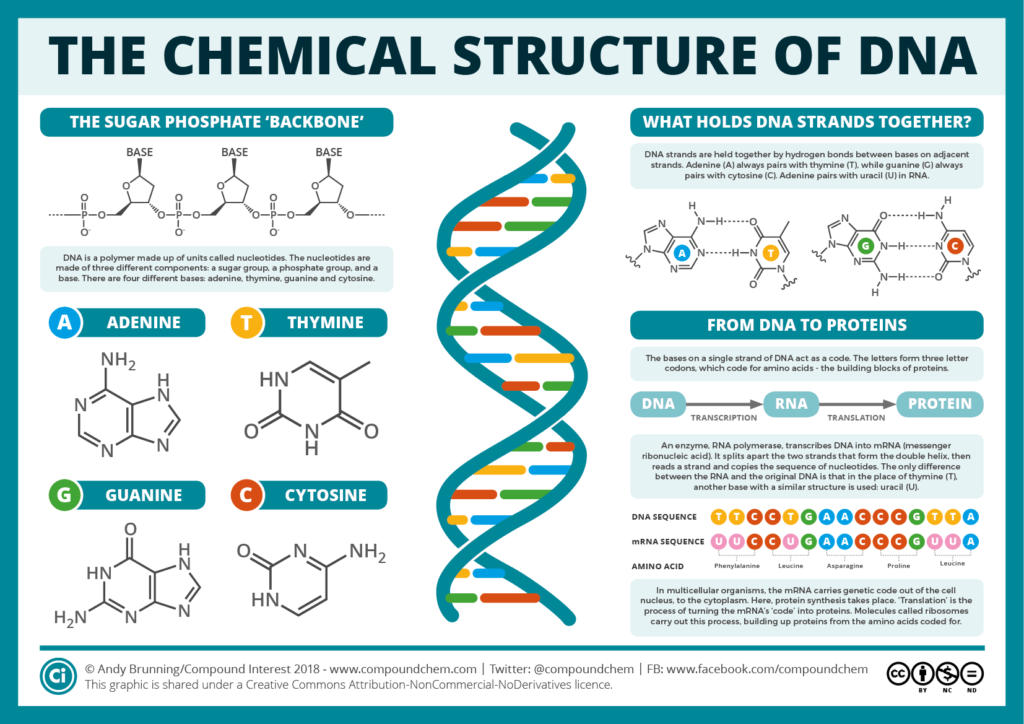

Note: Chemically, DMSO is (CH3)2SO which is one atom of carbon, three atoms of hydrogen, two atoms of sulfur, and one atom of oxygen—a stable and harmless mix.

However, according to the Andresen theory, when medical staff applied intense oxygen to Ramirez, the DMSO chemically changed by adding another oxygen atom to the formula—becoming (CH3)2SO2—dimethyl sulfone (DMSF). DMSF, also, is harmless and it’s commonly found in plants and marketed as a dietary supplement. So far, so good.

It’s when four oxygen atoms are present that the stuff turns nasty. The compound (CH3)2SO4 is called dimethyl sulfate, and it emits terribly toxic gas-offs. This is what Andresen suspected was the smoking gun. The amplified oxygenation turned the self-medicating dimethyl sulfoxide Ramirez was taking into dimethyl sulfone which morphed into the noxious emission, dimethyl sulfate.

The coroner liked it. So did many leading scientists. The coroner released Andresen’s report as an addendum to his final report, even though all agreed that if dimethyl sulfate was gassed-off by Ramirez in the ER that made so many people sick, it had absolutely nothing to do with the Toxic Lady’s death. The coroner closed his file, and the finding went on to be published in the peer-reviewed publication Forensic Science International.

There were two problems with Andresen’s conclusion. One was more scientists were disagreeing with it than agreeing. Some of the dissenters were world-class toxicologists who said it was chemically impossible for hospital-administered oxygen to set off this reaction. Two was Ramirez’s family adamantly denied she was self-medicating with DMSO.

The Toxic Lady case interest was far from over. Many people knew DSMO would be present in minute amounts in most people’s bodies and called bullshit. It’s a common ingredient in processed food and metabolizes well with a quick pass-through rate in the urinary tract. In Ramirez’s case, she had a urinary tract blockage which triggered the renal failure which triggered the heart attack. If it wasn’t for the blockage, the DSMO probably wouldn’t have been detected.

On the sidelines, there were people—knowledgeable people—strongly saying another chemical would give the same ammonia-like, gassing-off toxins that ticked all the 23-person symptom boxes.

Methylamine.

Methylamine isn’t rare. It’s produced in huge quantities as a cleaning agent, often shipped in pressurized railroad cars, but it’s tightly controlled by the government. That’s because methylamine can be used for biological terrorism and for cooking meth.

Yes, methylamine is a highly sought-after precursor used in manufacturing methamphetamines. Remember Breaking Bad and the lengths Walt and Jesse go to steal methylamine? Remember the precautions they take in handling methylamine?

Yes, methylamine is a highly sought-after precursor used in manufacturing methamphetamines. Remember Breaking Bad and the lengths Walt and Jesse go to steal methylamine? Remember the precautions they take in handling methylamine?

Well, back before Breaking Bad broke out, the New Times LA ran a story giving an alternative theory of what happened to make the Toxic Lady toxic. Whether the Times got a tip, or some inside information, they didn’t say. What they did say was that Riverside County was one of the largest methamphetamine manufacturing and distribution points in America, and that Riverside hospital workers had been smuggling out methylamine to sell to the meth cookers. (Hospitals routinely use methylamine as a disinfectant in cleaning agents, including sterilizing surgical instruments.)

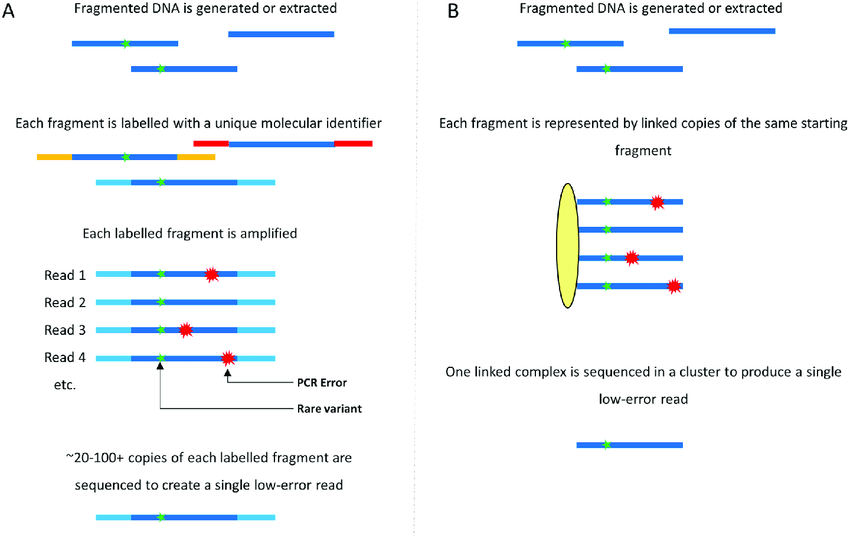

The Times report said Riverside hospital workers used IV bags to capture and store methylamine as the IV bags were sealed, safe to handle, and entirely inconspicuous. The story theorized that an IV bag loaded with about-to-be smuggled methylamine accidentally found its way into the ER and got plugged into Gloria Ramirez’s arm. Because methylamine turns to gas so quickly when exposed to oxygen, this would explain why no traces were found in the toxicology testing—it all went into the air and into the lungs of 23 people.

———

As a former coroner, I’d be skeptical of this methylamine theory except for personal knowledge of a similar case. My cross-shift attended a death where a meth cooker had methylamine get away from him in a clandestine lab. The victim made it outside yelling for help but shortly succumbed. The civilians, hearing his cries, rushed over and were immediately overpowered with the exact symptoms as the Riverside medical people experienced.

The first responders also succumbed to toxic fumes and had to back off. By the time my cross-shift arrived to view the body, many contaminated people were already at the hospital. My colleague made a wise decision. He signed-off the death as an accident, declined to autopsy, and sent the body straight to the crematorium—accompanied by guys in hazmat suits with the body sealed in a metal container and strapped to a flat deck truck.

The first responders also succumbed to toxic fumes and had to back off. By the time my cross-shift arrived to view the body, many contaminated people were already at the hospital. My colleague made a wise decision. He signed-off the death as an accident, declined to autopsy, and sent the body straight to the crematorium—accompanied by guys in hazmat suits with the body sealed in a metal container and strapped to a flat deck truck.

Do I buy the Times methylamine theory? Well, I’m a big believer in Occam’s razor. You know, when you have two conflicting hypotheses for the same puzzle, the simpler answer is usually correct. Some one-in-a-billion, complex chemical reaction that world-leading toxicologists say can’t be done? Or some low-life, crooked hospital drone letting an IV bag full of stolen methylamine get away on them?

You know which one I’m going with to explain the bizarre death of the Toxic Lady — Gloria Ramirez.