The 1845 expedition led by Sir John Franklin to find the Northwest Passage was one of the biggest disasters in exploration history. Despite being outfitted with the best provisions and equipment of the time, the entire complement of 129 officers and men aboard the British Royal Navy ships HMS Erebus and the HMS Terror perished in the wilds of the frozen north. It was the nineteenth century’s equivalent to having lost the International Space Station.

The 1845 expedition led by Sir John Franklin to find the Northwest Passage was one of the biggest disasters in exploration history. Despite being outfitted with the best provisions and equipment of the time, the entire complement of 129 officers and men aboard the British Royal Navy ships HMS Erebus and the HMS Terror perished in the wilds of the frozen north. It was the nineteenth century’s equivalent to having lost the International Space Station.

The cause of what truly led to the demise of the Franklin Expedition has fascinated historians and scientists for years, creating many theories based on scarce evidence. In 2014, the well-preserved wreck of the Erebus was found on the sea floor near King William Island in Canada’s Arctic. It’s discovery renewed interest in Franklin’s fate and a look through modern forensics tells a tale of how the ships’ cutting-edge technology probably snuck up to kill the crew.

First, a look at some history.

The Franklin Expedition was commissioned by the British Admiralty to do more than just find the elusive Northwest Passage. It was also a scientific venture to record the Arctic’s flora and fauna, map the terrain, observe magnetism and meteorology, inspect geology, and establish Commonwealth sovereignty in the north.

The Franklin Expedition was commissioned by the British Admiralty to do more than just find the elusive Northwest Passage. It was also a scientific venture to record the Arctic’s flora and fauna, map the terrain, observe magnetism and meteorology, inspect geology, and establish Commonwealth sovereignty in the north.

The voyagers were equipped with the finest navigation instruments and stocked with ample provisions to survive far longer than the planned three-year venture. The ships had been specifically refitted to withstand crushing ice pressures and upgraded with inboard steam engines to assist in turning through the maze of ice, as well as for the first time having an onboard desalination plant for turning seawater into fresh.

They debarked England on May 19, 1845 and made their first stop in Greenland to top off supplies. Already five crew members were ill and were discharged back home. The expedition departed and was last seen by other Europeans from two whaling ships in August in the vicinity of Lancaster Sound at the entrance to the Passage.

History shows the Franklin Expedition camped the winter of 1845-1846 on Beechey Island where later parties discovered artifacts and the graves of three sailors. When the Expedition failed to return to England in 1849—a year after planned—search parties were formed and a slight trail of clues was discovered to shed light on their fate.

History shows the Franklin Expedition camped the winter of 1845-1846 on Beechey Island where later parties discovered artifacts and the graves of three sailors. When the Expedition failed to return to England in 1849—a year after planned—search parties were formed and a slight trail of clues was discovered to shed light on their fate.

The only document recovered was a note in a rock cairn on King William Island stating the ships had been ice-locked for nineteen months and were abandoned on April 22, 1848, three days before the note was written. It also advised that Sir John Franklin died on June 11, 1847 and that the remaining 105 officers and men were attempting to venture by land for a Canadian mainland settlement at Back’s Fish River. None made it.

Progressive searches over ten years found pieces of human skeletons and artifacts that were proven to have come from the Franklin party, however no mass death site was located and their final demise was attributed to starvation and exposure.

The Franklin story and explanation for what caused a perfectly outfitted expedition of experienced explorers who prepared for these exact conditions and time interval never strayed from public interest.

In 1981, a team of scientists led by Dr. Owen Beattie, a professor of anthropology, began a forensic examination of the Beechey Island wintering site, including an exhumation of the crew members’ graves in hopes of determining their cause of death. This is documented in the great book Frozen In Time – The Fate Of The Franklin Expedition.

In 1981, a team of scientists led by Dr. Owen Beattie, a professor of anthropology, began a forensic examination of the Beechey Island wintering site, including an exhumation of the crew members’ graves in hopes of determining their cause of death. This is documented in the great book Frozen In Time – The Fate Of The Franklin Expedition.

What Dr. Beattie’s team found was truly remarkable—not just in eventual toxicology evidence—but in the incredibly well-preserved condition the bodies were in, given they’d spent over 135 years in the permafrost.

The team autopsied John Torrington, John Hartnell, and William Braine, concluding that pneumonia was possibly their primary cause of death, with tuberculosis maybe being a contributor. Otherwise, they appeared perfectly healthy. Malnutrition, chronic disease, foul play, or any form of accidental death was ruled out.

The team autopsied John Torrington, John Hartnell, and William Braine, concluding that pneumonia was possibly their primary cause of death, with tuberculosis maybe being a contributor. Otherwise, they appeared perfectly healthy. Malnutrition, chronic disease, foul play, or any form of accidental death was ruled out.

Being diligent, the team later ordered toxicology screening including a test for trace elements in the tissues, blood, bone, and hair. The results astounded them. All three sailors showed a presence of lead in amounts far, far exceeding normal levels. Braine, the last to die, showed 220 parts per million (ppm) in his hair, which is over one hundred times the acceptable level.

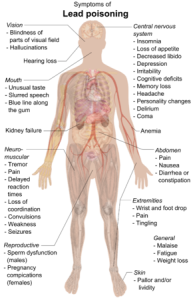

This led to a theory that the crew may have perished as a progressive result of lead poisoning with known side effects being a loss of cognitive awareness and the eventual inability for organs to function.

The team continued their search of the suspected southward trail of the doomed expedition and found considerable pieces of human skulls and bones which were anthropologically linked to European Caucasians, giving proof they must have belonged to the Franklin group. Every single bone contained an exceptionally high lead content. In total, the remains of thirty-two different individuals were identified. What became of the other seventy-five percent of the Franklin crew who abandoned the ships is a mystery.

The team continued their search of the suspected southward trail of the doomed expedition and found considerable pieces of human skulls and bones which were anthropologically linked to European Caucasians, giving proof they must have belonged to the Franklin group. Every single bone contained an exceptionally high lead content. In total, the remains of thirty-two different individuals were identified. What became of the other seventy-five percent of the Franklin crew who abandoned the ships is a mystery.

Pursuing the lead poisoning theory, suspicion fell on the lead solder used in the tin-canned provisions of meat and vegetables which the ships stored. Inventory records show the Erebus and the Terror held over 8,000 tins of preserves each with a total weight of 33,289 pounds.

With the British being ones to keep meticulous records, the tin-can contract was documented to have gone to a London food processor named Stephan Goldner. The low-bid contract was awarded late in the Expedition’s outfitting process and Goldner’s company was under a huge rush to complete on time. To speed the delivery and to profit more, Goldner began using larger containers and slipped on the quality control.

With the British being ones to keep meticulous records, the tin-can contract was documented to have gone to a London food processor named Stephan Goldner. The low-bid contract was awarded late in the Expedition’s outfitting process and Goldner’s company was under a huge rush to complete on time. To speed the delivery and to profit more, Goldner began using larger containers and slipped on the quality control.

Examination of the numerous discarded cans in the Beechey Island site’s garbage pile showed that the soldering on most cans was very sloppy with big gobs of solder spots on the interiors. It appeared Goldner’s greed and rush may have doomed the Franklin expedition.

However—digging deeper into the Goldner tin-can theory, it was recorded that Goldner had been providing the Royal Navy with lead-soldered canned goods for years before, and for years after, the Franklin fate and there were absolutely no reports of anyone suffering from lead poisoning anywhere within the rest of the British fleet.

However—digging deeper into the Goldner tin-can theory, it was recorded that Goldner had been providing the Royal Navy with lead-soldered canned goods for years before, and for years after, the Franklin fate and there were absolutely no reports of anyone suffering from lead poisoning anywhere within the rest of the British fleet.

Additionally, reports from the Inuit people who came in contact with the Franklin crew near their end indicated the members were in starvation—half-mad and resorting to cannibalism. This was forensically corroborated by striation marks on many bones which were consistent with disarticulation and the mechanical stripping of flesh.

Curiously, it appeared that the crew was starving—desperately short of food in less than three years after embarking with stores that were capable of lasting five years, if properly rationed. Combined with the extremely high lead content in the sailors, it was evident something else was amiss.

Now, between 1818 and 1845 the British Admiralty instigated ten ship-borne Arctic and Antarctic expeditions, three of which Sir John Franklin was part of. These folks were no strangers to cold, harsh, and lengthy trips. After Franklin’s disappearance, thirty-six separate search expeditions were conducted into the Northwest passage. While a few men perished and a few ships were destroyed, none of these expeditions suffered such a total and devastating loss as did Franklin.

Now, between 1818 and 1845 the British Admiralty instigated ten ship-borne Arctic and Antarctic expeditions, three of which Sir John Franklin was part of. These folks were no strangers to cold, harsh, and lengthy trips. After Franklin’s disappearance, thirty-six separate search expeditions were conducted into the Northwest passage. While a few men perished and a few ships were destroyed, none of these expeditions suffered such a total and devastating loss as did Franklin.

Clearly it was evident there was some unique and fatal flaw in the Franklin Expedition and it was thought it must have something to do with the lead.

William Battersby is a British Naval Architect who published a brilliant report titled Identification of the Probable Source of the Lead Poisoning Observed in Members of the Franklin Expedition.

Battersby identified what was different on board the Erebus and the Terror than on all other Royal Naval vessels, before or since. Remember, these two ships were refitted for this lengthy voyage into a harsh, frozen land and they carried with them new technology specifically designed for these two ships—a new infrastructure for desalination—for turning salty seawater into drinkable freshwater.

Battersby identified what was different on board the Erebus and the Terror than on all other Royal Naval vessels, before or since. Remember, these two ships were refitted for this lengthy voyage into a harsh, frozen land and they carried with them new technology specifically designed for these two ships—a new infrastructure for desalination—for turning salty seawater into drinkable freshwater.

This was a complicated system as it was not just distilled, potable freshwater for consumption that the system was providing. It also produced freshwater for the engines’ steam boilers as well as making hot water for the ships’ heating systems.

And—you guessed it—the system’s entire plumbing was made of lead pipes soldered together with lead.

And—you guessed it—the system’s entire plumbing was made of lead pipes soldered together with lead.

“Wait a minute,” you say. “Humans have been using lead pipes for plumbing since the days of the Romans and nobody’s been reported to have died from them.”

Hang on. There was something really unique going on aboard the Erebus and the Terror that affects how lead transfers from water into blood.

Here’s a quote from Battersby’s report:

The amount of lead absorbed by water from lead pipes or solders greatly increases where:

- Water is soft, such as when freshly distilled.

- An installation is new and has not built up a layer of scale. Scale insulates water in older installations from direct contact with lead.

- Water is warm or hot. This dramatically increases the amount of lead which water can carry.

All these conditions applied to the installations in the HMS Erebus and Terror.

“Interesting theory, Garry”, you say. “I buy it was the pipes, not the cans, where the high concentration of lead came from, but how do you explain the starvation when there was ample canned food to go around?”

“Interesting theory, Garry”, you say. “I buy it was the pipes, not the cans, where the high concentration of lead came from, but how do you explain the starvation when there was ample canned food to go around?”

Great question and I think Scott Cookman might have answered it in his book Ice Blink – The Tragic Fate Of Sir John Franklin’s Lost Polar Expedition.

Cookman’s theory is that in Stephan Goldner’s greedy rush to drop quality control standards, he failed to cook the preserves at a high enough heat for a long enough time, thereby introducing botulism in a portion of the cans.

It falls into the facts that early in the voyage, five sick crew members were discharged and then three seemingly healthy, well-nourished sailors—Torrington, Hartnell, and Braine—suddenly up and died.

The theory continues that once the magnitude of the tainted canned-food scandal became apparent, the Franklin Expedition was solidly locked in ice and forced to exhaust the remaining stores of flour and beans—all which would be cooked in heavy-lead water.

Once the edible food stores ran out, the crew made a desperate, lead-poisoned and half-mad trek across land and probably perished, one-by-one, with the last of them insanely resorting to cannibalism.