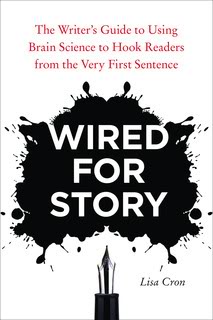

Lisa Cron’s book Wired For Story was a writing ‘A-Hah’ moment for me. I’m so pleased to to have Lisa share this game-changing information as a guest at DyingWords.net.

What would you say if I told you that what the brain craves, hunts for, and responds to in every story it hears has nothing to do with what most writers are taught to strive for? What’s more, that it’s the same thing whether you’re writing literary fiction or a down and dirty thriller?

What would you say if I told you that what the brain craves, hunts for, and responds to in every story it hears has nothing to do with what most writers are taught to strive for? What’s more, that it’s the same thing whether you’re writing literary fiction or a down and dirty thriller?

You’d probably say, prove it. Fair enough.

First, the mistaken belief: From time immemorial we’ve been taught that things like lyrical language, insightful metaphors, vivid description, memorable characters, palpable sensory details, and a fresh voice are what hooks readers.

First, the mistaken belief: From time immemorial we’ve been taught that things like lyrical language, insightful metaphors, vivid description, memorable characters, palpable sensory details, and a fresh voice are what hooks readers.

It’s a seductive belief, because all those things are indisputably good. But they’re not what hook the reader. The brain, it turns out, is far less picky when it comes pretty prose than we’ve been led to believe.

What does the brain crave?

Beginning with the very first sentence, the brain craves a sense of urgency that instantly makes us want to know what happens next. It’s a visceral feeling that seduces us into leaving the real world behind and surrendering to the world of the story.

Beginning with the very first sentence, the brain craves a sense of urgency that instantly makes us want to know what happens next. It’s a visceral feeling that seduces us into leaving the real world behind and surrendering to the world of the story.

Which brings us to the real question: Why? What are we really looking for in every story we read? What is that sense of urgency all about?

Thanks to recent advances in neuroscience, these are questions that we can now begin to answer with the kind clarity that sheds light on the genuine purpose of story and elevates writers to the most powerful people on earth. Because story, as it turns out, has a much deeper and more meaningful purpose than simply to entertain and delight.

Story is how we make sense of the world. Let me explain . . .

It’s long been known that the brain has one goal: survival. It evaluates everything we encounter based on a very simple question: Is this going to help me or hurt me? Not just physically, but emotionally as well.

It’s long been known that the brain has one goal: survival. It evaluates everything we encounter based on a very simple question: Is this going to help me or hurt me? Not just physically, but emotionally as well.

The brain’s goal is to then predict what might happen, so we can figure out what the hell to do about it before it does. That’s where story comes in.

By letting us vicariously experience difficult situations and problems we haven’t actually lived through, story bestows upon us, risk free, a treasure trove of useful intel – just in case.

And so back in the Stone Age, even though those shiny red berries looked delicious, we remembered the story of the Neanderthal next door who gobbled ‘em down and promptly keeled over, and made do with a couple of stale old beetles instead.

Story was so crucial to our survival that the brain evolved specifically to respond to it, especially once we realized that banding together in social groups makes surviving a whole lot easier.

Story was so crucial to our survival that the brain evolved specifically to respond to it, especially once we realized that banding together in social groups makes surviving a whole lot easier.

Suddenly it wasn’t just about figuring out the physical world, it was about something far trickier: navigating the social realm.

In short, we’re wired to turn to story to teach us the way of the world and give us insight into what makes people tick, the better to discern whether the cute guy in the next cubicle really is single like he says, and to plan the perfect comeuppance if he’s not.

The sense of urgency we feel when a good story grabs us is nature’s way of making sure we pay attention to it. It turns out that intoxicating sensation is not arbitrary, ephemeral or “magic,” even though it sure feels like magic. It’s physical. It’s a rush of the neural pleasure transmitter, dopamine. And it has a very specific purpose.

The sense of urgency we feel when a good story grabs us is nature’s way of making sure we pay attention to it. It turns out that intoxicating sensation is not arbitrary, ephemeral or “magic,” even though it sure feels like magic. It’s physical. It’s a rush of the neural pleasure transmitter, dopamine. And it has a very specific purpose.

Want to know what triggers it?

Curiosity.

When we actively pursue new information – that is, when we want to know what happens next — curiosity rewards us with a flood of dopamine to keep us reading long after midnight because tomorrow we just might need the insight it will give us.

When we actively pursue new information – that is, when we want to know what happens next — curiosity rewards us with a flood of dopamine to keep us reading long after midnight because tomorrow we just might need the insight it will give us.

This is a game changer for writers.

It proves that no matter how lyrical your language, or how memorable your characters, unless those characters are actively engaged in solving a problem – making us wonder how they’ll get out of that one – we have no vested interest in them.

We can’t choose whether or not to respond to story. Dopamine makes us respond. Which is probably why so many readers who swear they only read highbrow fiction are surreptitiously downloading Fifty Shades of Grey. I’m just saying.

We can’t choose whether or not to respond to story. Dopamine makes us respond. Which is probably why so many readers who swear they only read highbrow fiction are surreptitiously downloading Fifty Shades of Grey. I’m just saying.

I know that many writers will want to resist this notion. After all, the brain is also wired to resist change and to crave certainty.

And for a long time writers were certain that learning to “write well” was the way to hook the reader.

So embracing a new approach to writing – even though it’s based on our biology, and how the brain processes information — probably feels scary. The incentive to focus on story first and “writing” second, however, is enormous. To wit:

So embracing a new approach to writing – even though it’s based on our biology, and how the brain processes information — probably feels scary. The incentive to focus on story first and “writing” second, however, is enormous. To wit:

- You’ll reduce your editing time exponentially because story tends to be what’s lacking in most rough drafts. Polishing prose in a story that’s not working is like rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

- You’ll have a 1000% better chance of getting the attention of agents, editors and publishers. Yeah, 1000% is arbitrary, but it’s not far off. These professionals are highly trained when it comes to identifying a good story. They like good writing as much as a next person – but only when it’s used to tell a good story.

- You’ll have a fighting chance of changing the world – and I’m not kidding. Writers are the most powerful people on the planet. They can capture people’s attention, teach them something new about themselves and the world, and literally rewrite the brain – all with a well-told tale.

Indeed, the pen is far mightier than the sword.

That is, if you know how to wield it.

* * *

Lisa Cron is the author of Wired for Story: The Writer’s Guide to Using Brain Science to Hook Readers From the Very First Sentence (Ten Speed Press). I’m thrilled to have Lisa share her knowledge, observations, and wisdom through this guest post at DyingWords.net.

Lisa Cron is the author of Wired for Story: The Writer’s Guide to Using Brain Science to Hook Readers From the Very First Sentence (Ten Speed Press). I’m thrilled to have Lisa share her knowledge, observations, and wisdom through this guest post at DyingWords.net.

Wired For Story caused me to go right back to square one and revise my No Witnesses To Nothing manuscript. For someone like me who comes from a totally anal adherence to science, I had a Eureka moment when I Lisa showed me the straightforward science of storytelling. Our brains are hard-wired for stories – always have been, always will be. This is a science ap for a page-turner. I’m serious. If you want to bring up your writing game… READ THIS BOOK!

Wired For Story caused me to go right back to square one and revise my No Witnesses To Nothing manuscript. For someone like me who comes from a totally anal adherence to science, I had a Eureka moment when I Lisa showed me the straightforward science of storytelling. Our brains are hard-wired for stories – always have been, always will be. This is a science ap for a page-turner. I’m serious. If you want to bring up your writing game… READ THIS BOOK!

Lisa has worked in publishing at W.W. Norton, as an agent at the Angela Rinaldi Literary Agency, as a producer on shows for Showtime and CourtTV, and as a story consultant for Warner Brothers and the William Morris Agency. Since 2006, she’s been an instructor in the UCLA Extension Writers’ Program.

Lisa works with writers, nonprofits, educators and organizations, helping them master the unparalleled power of story, so they can move people to action – whether that action is turning the pages of a compelling novel, trying a new product, or taking to the streets to change the world for the better.

Lisa’s literary agent is Laurie Abkemeier at DeFiore and Company.

Her video tutorial Writing Fundamentals: The Craft of Story can be found at Lynda.com.

Watch Lisa’s Ted Talks video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=74uv0mJS0uM

Visit her website at http://wiredforstory.com/

Follow on Twitter https://twitter.com/LisaCron

Here the Wired For Story Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/pages/Wired-For-Story/116220388438647