We’ve all seen them. Those walking zombies aimlessly lost with their face in their phones and utterly oblivious to the forest, the trees, and the traffic. They’re devastatingly distracted by the Kim Kardashian of happiness molecules—dopamine—hopelessly and unknowingly addicted to their next rush of digital downloads fixed by non-stop scrolls.

We’ve all seen them. Those walking zombies aimlessly lost with their face in their phones and utterly oblivious to the forest, the trees, and the traffic. They’re devastatingly distracted by the Kim Kardashian of happiness molecules—dopamine—hopelessly and unknowingly addicted to their next rush of digital downloads fixed by non-stop scrolls.

This is a relatively new phenomenon, and it’s married at the hip to digital information dictated by the internet; digital devices and internet content controlled by the tech giants gaining ground on the entertainment industry. It’s here, and it’s not going away. At best, the digital dopamine addiction can only be controlled.

What’s sad is this dopamine distraction is harming society’s young. So many teens and twenties are hooked on their smartphones. Statistics say youths around the world spend far more time connected to the web than playing with their peers. The digital pandemic is so sick that it’s created an industry of wellness trying to treat digital dopamine addiction.

It’s also radically changed the entertainment world as well as the online support systems where Big Tech carries market cap values into the trillions of dollars. And those Big Tech titans are intentionally designing their algorithms to purposely distract viewers from facing reality. We’ll get into what’s going on in Tech, the downfall of the entertainment industry, how algorithms work, what dopamine is, and what motivates psychopath billionaires like Mark Zuckerburg to digitally prey on innocent and unsuspecting tweens.

What got me going on this piece was an article by Ted Gioia (The Honest Broker). The title is The State of Culture, 2024. These opening lines grabbed me. “Not much changes in politics. Certainly not the candidates. So, forget about politics. All the action is happening in mainstream culture—which is changing at warp speed. 2024 will be the most fast-paced—and dangerous—time ever for the creative economy. I want to tell you why entertainment is dead. And what’s coming to take its place.”

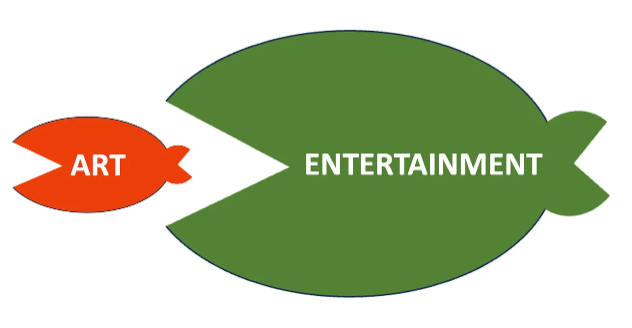

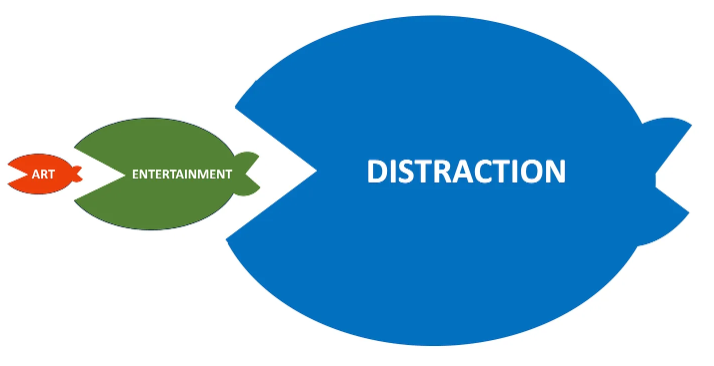

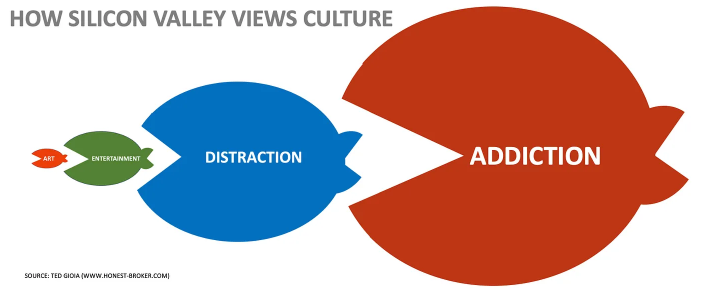

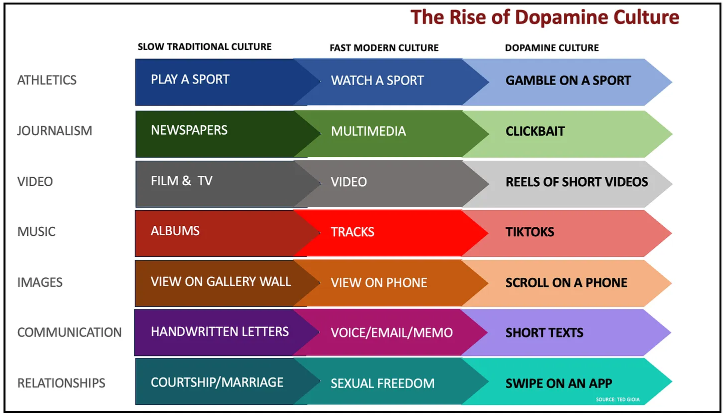

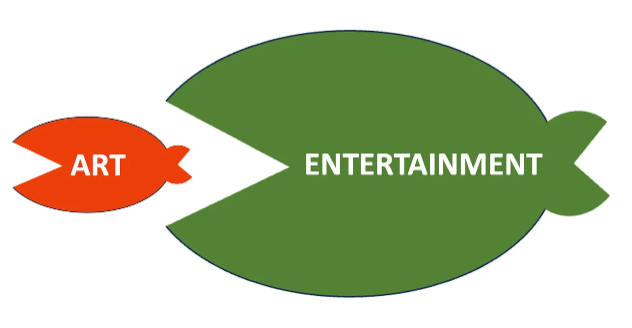

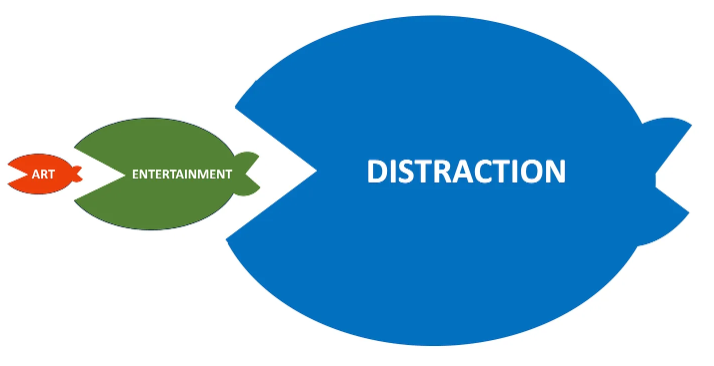

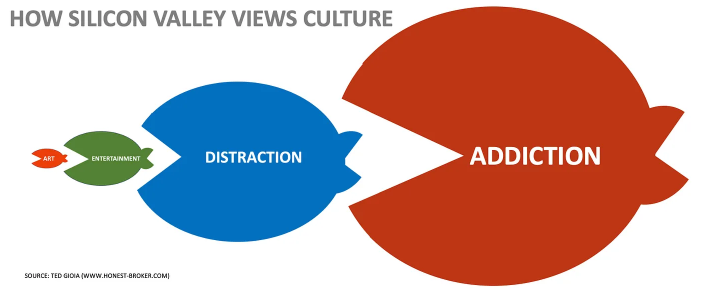

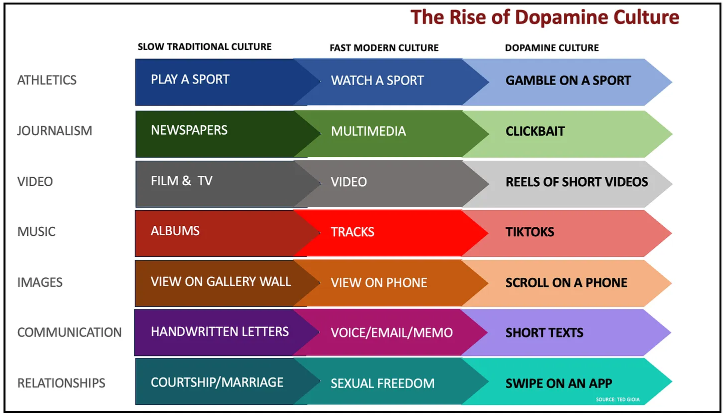

Mr. Gioia continues on to explain how the bigger entertainment shark once ate the little art fish. Then how the huge distraction whale swallowed the shark which, in turn, was devoured by the colossal addiction monster. He equates it to a cultural food chain and demonstrates it with these graphics:

It’s always been hard to be an artist. In the entertainment business, the primary artist is the content producer or concept developer. We were once called writers.

Until recently, the entertainment industry had been on a growth roll. So much so, that any content considered artsy was crushed as collateral damage by the forces of ever-needed new shows—regardless of if the productions were good or not.

That’s suddenly changed. It won’t help the art fish and it won’t help the shark. It won’t even help the whale because the whole online world is moving to a distraction model. And that’s to serve the phenomenon of dopamine addiction caused by the short and extremely fast pace of stimuli like reels, toks, clicks, instas, tubes, pushes, autoplays, variable rewards, and infinite scrolling. It’s an addictive distraction game, and it’s played colossally well by the Big Tech algorithms.

The fastest growing sector of the culture economy is distraction. Call it scrolling or swiping or wasting time or whatever you want. But don’t call it art or entertainment. It’s just ceaseless activity and is highly addictive because each short piece causes a dopamine release. Yes, the tech builders know it and it’s planned that way.

The key to the distraction model is that each stimulus only lasts a few seconds. To maintain the dopamine rush, the stimuli must be repeated. Over and over and over and over.

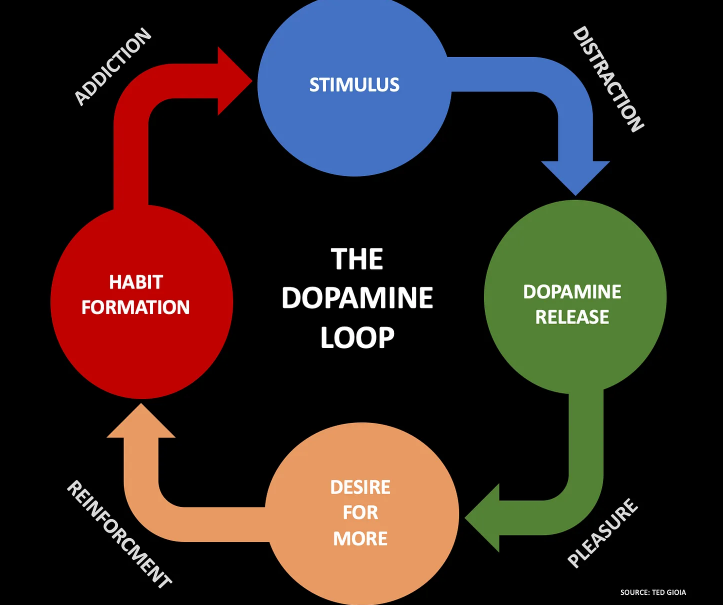

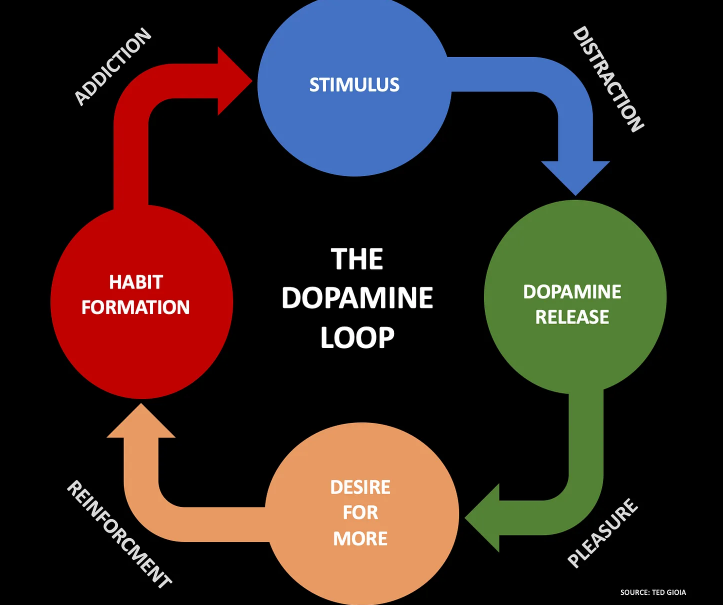

Gioia’s article says this is not just the hot trend for 2024. It can last forever because the distraction model is based on body chemistry, not on fashion or art. Our brains are wired to reward brief bursts of distraction by smoothing us with a dopamine hit. He calls it the Dopamine Loop and it looks like this:

This is the familiar cycle of addiction. Now, through the online distraction model, it’s being applied to the culture and creative world—and billions of people. They (we) are unwitting volunteers in the biggest social engineering experiment ever unleashed in human history.

Tech wants to create a world of junkies where Tech will be the pushers and dealers. Addiction is the goal. They don’t say it openly. They don’t need to. Just look at what they do.

- Everything is being designed to lock users into an addictive cycle.

- Platforms are shifting to scrolling and reeling interfaces.

- Algorithms punish you for leaving sites.

There’s more. Apple, Facebook, and others want you to wear their virtual reality goggles. They are specifically made to swallow you through stimuli like the tiny fish in the food chain charts. You’re invited to live as a passive recipient of make-believe like a pod slave in The Matrix.

This is the new culture, and it’s here in 2024. Instead of movies and TV shows, we’re being served an endless stream of seconds-long vids. Instead of symphonies, we’re satisfied with sound bits, usually accompanied by a slick little pic.

The most striking feature of the new culture is the absence of culture. It’s mindless entertainment—escapism—of compulsive activity. It’s the dopamine culture.

Here’s where the science gets ugly. The more addicts rely on stimuli for their fix, the less pleasure they get. At a certain point, which our brains are designed for, this cycle creates anhedonia. That’s the medical word for the complete absence of enjoyment.

Dopamine deprivation takes over and the addict is broken. The scrolling cycle causes pain, not pleasure, and the pain causes more pain as the addict scrolls. It becomes a hopeless cycle and a spiraling downfall.

To quote Ted Gioia, “Some companies get people hooked on pills and needles. Others with apps and algorithms. But either way, it’s just churning out junkies. That’s our dystopian future. Not so much Orwell’s 1984. It’s more like Huxley’s Brave New World.”

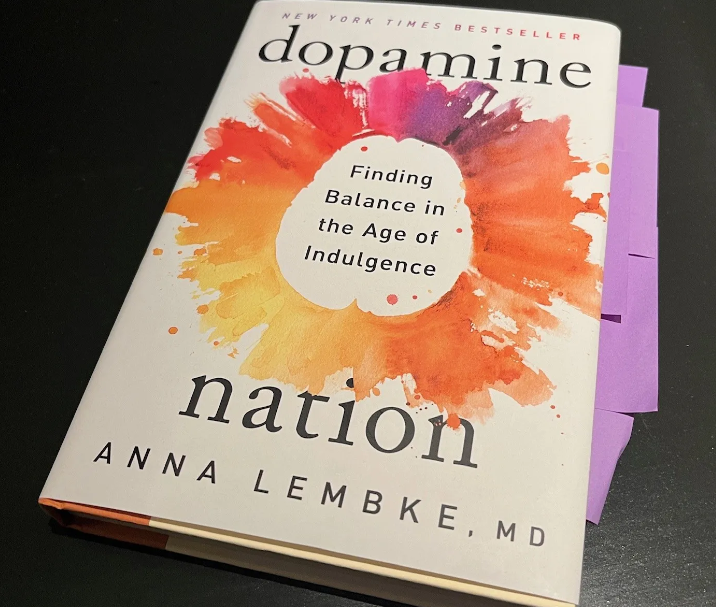

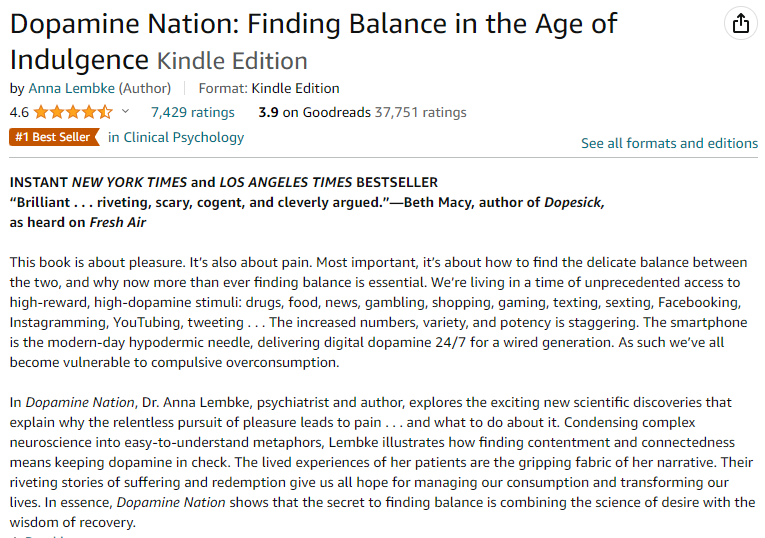

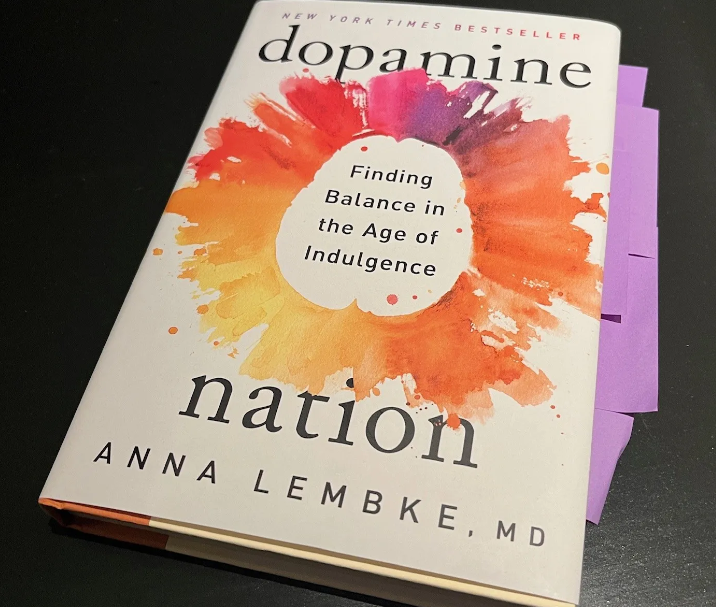

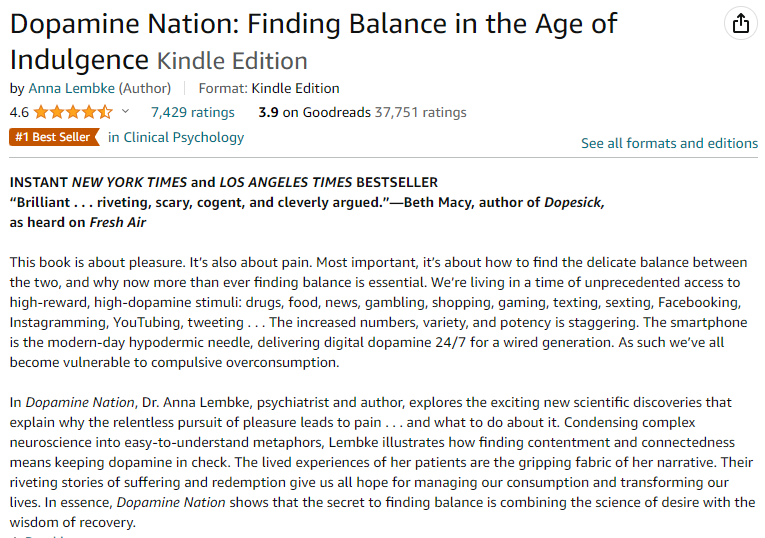

Dr. Anna Lembke is a world-leading addiction expert. She’s Chief of Staff at Stanford University’s Dual Diagnosis Addiction Clinic which deals with patients who have multiple addiction issues. Dr. Lembke wrote a recent book titled Dopamine Nation that topped the New York Times Bestseller List.

She calls the smartphone the modern-day hypodermic needle. As the doctor puts it, “We turn to it for quick hits, seeking attention, validation, and distraction with every swipe. Since the turn of the millennium, behavioral (as opposed to substance) addiction has soared. Every spare second is an opportunity to be stimulated, whether by entering the TikTok vortex, scrolling Instagram, swiping through Tinder, or binging on online porn, online gambling, or online shopping.”

Dr. Lembke refers to a World Happiness Report that clearly shows many people in high-income countries are far less happy than they were a few years ago. She blames this on the scroll-and-dopamine culture. “We’ve forgotten how to be alone with our thoughts. We’re forever interrupting ourselves for a quick digital hit, meaning we rarely concentrate on taxing tasks for long or get into a creative flow. The zone.”

Dr. Lembke continues to explain that addiction is a spectrum disorder. It’s not as simple as being an addict or not being an addict. Addiction is deemed worthy of clinical intervention and care when it significantly interferes with someone’s life and functioning ability. When it comes to digital addiction, she says, the effect is pernicious.

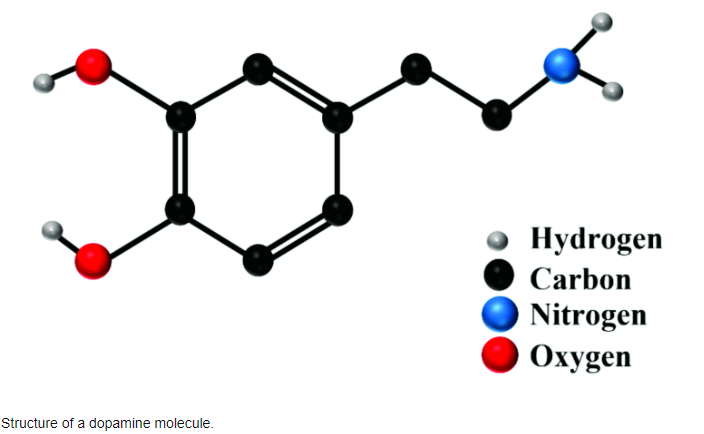

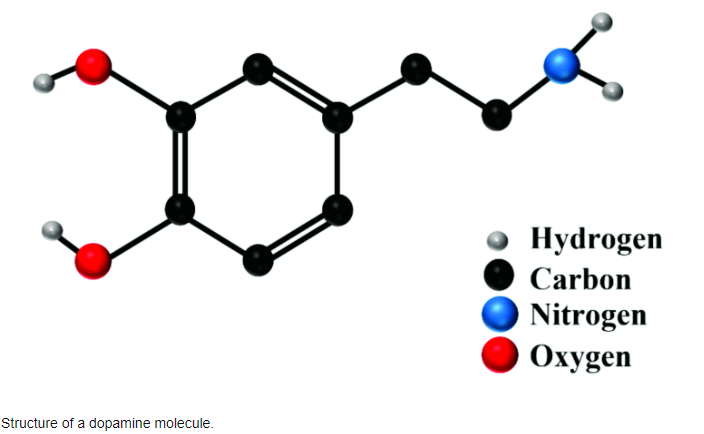

To understand addiction, you must first understand dopamine which she dubbed “The Kim Kardashian of molecules” owing to its mainstream prominence. Dopamine is a chemical often called “The Feelgood Hormone” and its molecular structure (resembling an insect with dual antennae and an offset tail) has even become a popular tattoo.

Rather than giving us pleasure itself, dopamine motivates us to do things we think will bring us pleasure. Like reading a fantastic book or watching a top-notch film. As the brain’s major reward and pleasure neurotransmitter, dopamine drives us to seek food when we’re hungry and sex when we’re horny. But there’s a side effect. The higher the dopamine release, the more addictive the thing.

“We experience a hike in dopamine in anticipation of doing the thing as well as actually doing it. As soon as it’s finished, we experience a comedown or dopamine dip. That’s because the brain operates through a self-regulating process termed homeostasis meaning for every high there’s a low. What we really want is that second piece of chocolate cake or to watch another episode but if we’re not severely addicted, the craving will soon pass.”

Scientists first identified dopamine in 1957. It’s a precursor to addiction with 50% due to genetics and 50% due to environmental excesses. The human brain hasn’t changed since 1957 but our access to additive things has incredibly increased. Exposure to the internet, for instance.

Where back in the ‘50s the focus was on family and work, reading and sports, today’s world gives you unlimited pleasure at the click of a mouse or loading an app. When we over-download pleasure, homeostasis causes our brain to bring us lower and lower. We sink into a joy-seeking abyss called anhedonia.

Immediate gratification defines the dopamine culture. It means we’re constantly living in our limbic brain which possesses emotions rather than in our pre-frontal cortex that plans for the future, solves problems, and develops personality. When we depend on our digital companions to help us escape life’s issues, the limbic system loves the distractions.

We need time away, Dr. Lembke prescribes. She recommends a 24-hour unplugging once a week or a least locking the phone in a drawer for an hour. I’m not a doctor, but I strongly prescribe Dr. Lembke’s book Dopamine Nation. Here’s a screenshot of its blurb on Amazon:

So, medically, what is dopamine? This natural drug that seduces and intoxicates addicts? Let’s use the web itself for a quick distraction.

Dopamine is a type of monoamine neurotransmitter produced by your brain to act as a reward center. It regulates functions like memory, movement, motivation, mood, attention, and more. Like happiness and escapism. It’s the chemical messenger connecting your nerve cells.

Dopamine plays a role in your fight or flight syndrome. It’s designed, from an evolutionary perspective to reward you when you’ve done well. As humans, we’re hardwired to seek pleasure and avoid pain. Dopamine is good in the short term but bad in the long.

We’ve talked about the drug, and we’ve talked about the addiction. We’ve talked about the culture, and we’ve talked about the change. Now let’s talk about the technology and who controls the algorithms that have changed the culture and sell the dopamine drug of addiction.

The word “algorithm” is everywhere. In print, online, and in AI—Artificial Intelligence. Facebook knows when you’ve been naughty, and it knows when you’ve been nice. Google knows more about you than your spouse does. ChatGPT? Like The Carpenters sang, “We’ve only just begun.”

So here I go again with Chat. (Sorry, Chat is here until AGI arrives and then…) I asked the tool-bot to explain, clearly and simply, what an algorithm is. It replied:

Algorithms are step-by-step instructions or procedures for solving a problem or completing a task. They’re like recipes for computers telling them what to do to achieve a specific goal. Here’s a breakdown of how algorithms operate:

- Input — Data, numbers, texts, habits

- Process — Organizing into logic

- Output — Results, conclusions, actions

It told me algorithms can be simple like processing numbers or extremely complex like algorithms used in AI programs such as ChatGPT. I also asked it how algorithms track our online behavior. It said:

- Data Collection — Watches and records what you’re doing

- Data Processing — Extracts meaningful information to its purpose

- Pattern Recognition — Figures out where you’ve been

- User Profiling — Figures out who you are

- Behavioral Prediction — Calculates what you want

- Feedback Loop — Checks to see if it’s right

Sound spooky? It does to me. Think of every time Facebook showed you something that aligned with your thoughts. I asked Chat how algorithms do this. What tools they use. It said:

- Cookies

- IP Address Tracking

- User Accounts and Profiles

- Pixels and Scripts

- Social Media Activity

- Browser History

During my chat with Chat, that insightful bot said something that made me think. It said, “User engagement and monetization can contribute to addictive patterns of behavior. It’s essential for tech companies to balance their business interests with ethical considerations and prioritize the well-being of their users.”

Tech companies own the internet. They have complete control over a user’s feed. Ultimately, their minds. Let’s look at the top five tech companies and their worth. As of yesterday, 23 February 2024, here are their stock market capitalization standings:

5. Meta — $1.21 Trillion

4. Amazon — $1.74 Trillion

3. Alphabet — $1.77 Trillion

2. Apple — $2.80 Trillion

1. Microsoft — $2.99 Trillion

Let’s not overlook Nvidia on this list of distraction builders. Nvidia makes the chips (the brains) that allow the techs to invent algorithms that addict their users to online dopamine dependence. This is Nvidia’s $1.72 Trillion stock market performance over the past five years:

It’s not only money that motivates Big Tech to mess with people’s minds and devastate their lives. It’s more than that. It’s power. Control. Manipulation. Dominance. Marketplace position. Not just stock market growth and capitalization.

As a distraction—maybe a digital dopamine hit—watch this four-minute clip of Mark Zuckerberg getting smoked over the coals of justice in a recent US Congressional hearing about harming children online. It’s worth the price of admission.

Some folks are nice and some folks are kind. There’s a difference, and you’ll recognize that difference when you read this wonderful, short essay written by Damola Morenikeji on his website bydamola.la. I found it through a link on The Morning Brew newsletter. It’s part of a new trend on Dyingwords where I find great works I feel will interest you and share them; hopefully you’ll share as well. With full attribution to Damola Morenikeji, here is “Kinda Nice”.

Some folks are nice and some folks are kind. There’s a difference, and you’ll recognize that difference when you read this wonderful, short essay written by Damola Morenikeji on his website bydamola.la. I found it through a link on The Morning Brew newsletter. It’s part of a new trend on Dyingwords where I find great works I feel will interest you and share them; hopefully you’ll share as well. With full attribution to Damola Morenikeji, here is “Kinda Nice”.