On February 19, 2013, Elisa Lam was found dead inside a 1,000-gallon water cistern on top of the notorious Cecil Hotel in the Skid Row District of downtown Los Angeles. Elisa, age 21, was reported missing 19 days earlier and was last seen in an elevator in the 14-story, 700-room hotel where she’d been staying. The L.A. Coroner ruled Elisa’s death an accident compounded by bizarre behavior caused by her previously diagnosed bipolar disorder. Her ghastly death was one more in a long series of outrageous events at The Cecil. As an LAPD officer put it, “The place is haunted. Tell me in which room a death hasn’t occurred.”

On February 19, 2013, Elisa Lam was found dead inside a 1,000-gallon water cistern on top of the notorious Cecil Hotel in the Skid Row District of downtown Los Angeles. Elisa, age 21, was reported missing 19 days earlier and was last seen in an elevator in the 14-story, 700-room hotel where she’d been staying. The L.A. Coroner ruled Elisa’s death an accident compounded by bizarre behavior caused by her previously diagnosed bipolar disorder. Her ghastly death was one more in a long series of outrageous events at The Cecil. As an LAPD officer put it, “The place is haunted. Tell me in which room a death hasn’t occurred.”

Elisa Lam’s bizarre death circumstances caught worldwide attention. Over the years, it’s developed an internet cult where outlandish theories are tossed about like a ghoulish parlor game. Some speculate on a paranormal event. Some speculate Elisa was part of a black-web Asian practice called the elevator game. There’s been so much macabre interest in the “Dead Lady in the Hotel Water Tank” case that in 2021 Netflix produced a 4-part series on it titled Crime Scene: The Vanishing at the Cecil Hotel.

There are two distinct stories in the Elisa Lam death case, and they merge in the end. One is the truly terrifying, final moments of Elisa’s death. The other is the horrible history of the hotel that housed at least two serial killers including the Night Stalker himself, Richard Ramirez. Let’s start with examining Elisa’s case facts and then look at the craziness confined in a haunted hotel.

The Death Investigation

Elisa Lam was born in Hong Kong and immigrated to Vancouver, Canada with her parents and sister. Elisa was a bright young lady and had been enrolled in the University of British Columbia. She ran several popular blogs and was a budding writer. However, Elisa suffered from depression and was clinically diagnosed with bipolar disorder. She was prescribed the usual medications—Lamotrigine, Quetiapine, Venlafaxine, and Bupropion (Wellbutrin). Although she’d been hospitalized for a psychotic event, Elisa had no background of suicidal tendencies.

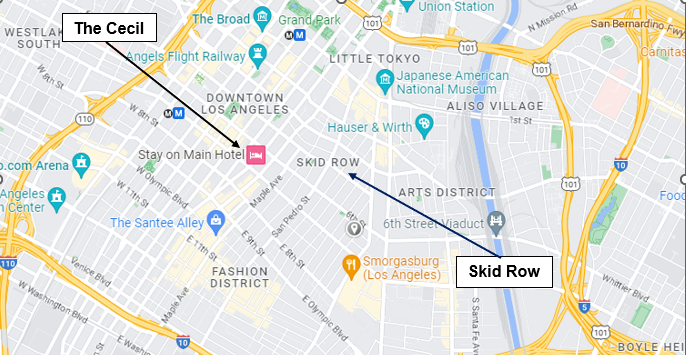

In early January 2013, Elisa took a post-Christmas sabbatical from her studies. She traveled alone via Amtrak and busses to Southern California, first to San Diego and then arriving in Los Angeles on January 26. Why she picked the Cecil Hotel is not known. Probably because The Cecil had been rebranded as Stay on Main (address 640 S. Main Street) to clean up its image as the worst lodging in the worst region of L.A. Bottomline—as a designated hostel, the price was now right.

Elisa initially roomed with two other young women. This quickly ended because of her behavior—giving entry passwords to the others and locking them out as well as leaving strange notes on their beds. Hotel staff moved Elisa to a single room where she could be alone. Then there was an episode in late January at a film studio (taping of Conan O’Brien) where Elisa was removed by security for disruptive behavior.

Elisa was last seen in person on January 31 in the hotel lobby. She’d kept in daily touch with her parents and sister. When she failed to connect on February 2, Elisa’s folks filed a missing persons report with LAPD.

Investigators checked the hotel’s video file and were satisfied Eliza never left the building through the main doors or fire escapes. What they did find was footage from February 1 where Elisa was alone in an elevator. In the 2-minute reel, Elisa portrayed seriously disturbed behavior. The video was released to the public before Elisa’s body was found, and it went viral, being viewed 33 million times on YouTube.

Before reading on, you must watch the clip to appreciate Elisa’s mental state. A picture is worth a thousand words and a video is priceless.

On February 19, a hotel maintenance worker responded to guest complaints that their water smelled bad, was a funny color, and the pressure was low. He checked the hotel’s four cisterns that were roof mounted to accommodate gravity pressure. These cisterns were steel tanks measuring 8 feet high and 4 feet in diameter. Access was through a removable upper hatch that could easily be removed by one person.

The worker found the lid open on the northeast tank. He looked inside and saw Elisa’s bloated and decomposing body floating face up on the surface—the water level being approximately 2 feet down from the top or 6 feet from the bottom and no way that 5-foot, 6-inch Elisa could have stood on the tank floor with her head in the air.

The L.A. Fire Department drained the tank and cut it open as removing Elisa’s body through the upper portal was impossible. Elisa was naked and her saturated clothes lay loose on the tank floor along with her watch and her hotel room key card. Inside her room, the rest of her belongings remained including her money, identification, and medications.

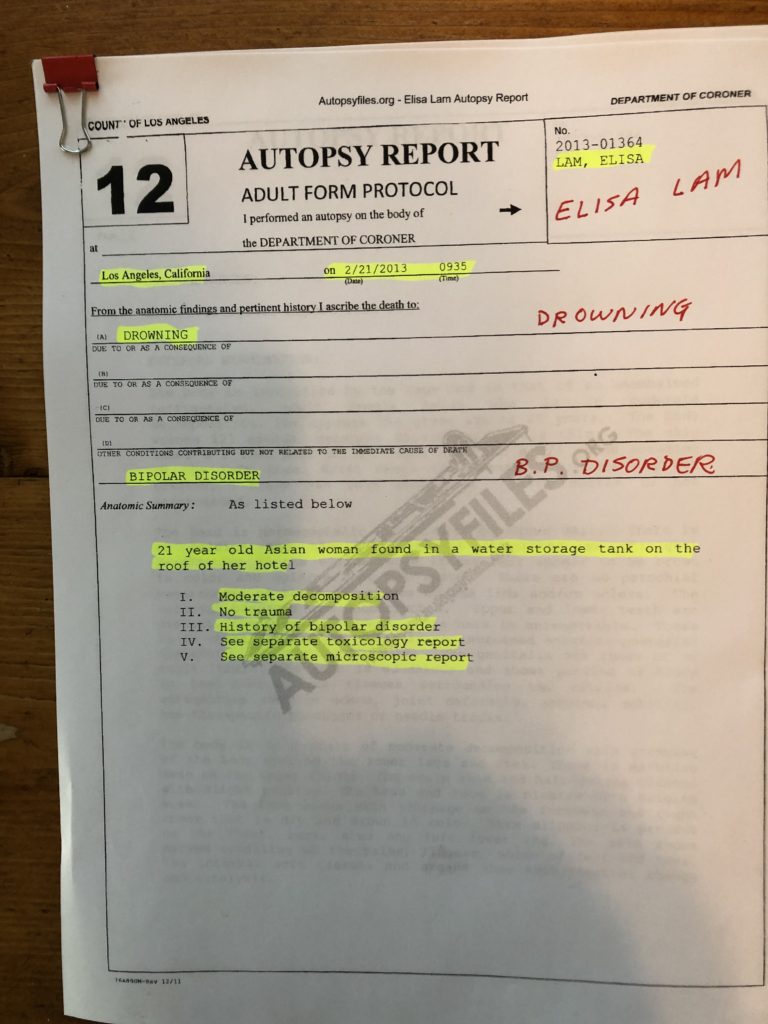

Elisa was autopsied on February 21. Aside from a ¼ inch round abrasion on her left knee, there was no sign of physical trauma. Her cause of death was clear—drowning. “Both pleural cavities contain dark brown fluid; 300 cc on the right and 200 cc on the left.”

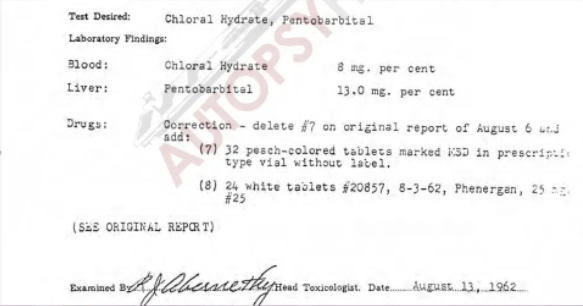

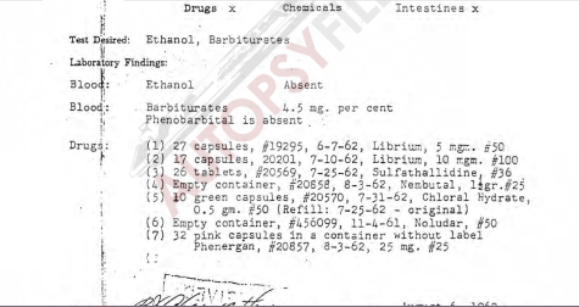

Her toxicology testing was not so clear. Her advancing state of decomposition—being dead approximately 21 days by autopsy time—left little blood in her heart or major arteries to examine. The toxicology report (considering blood, bile, and liver tissue) was conclusive that no normal street drugs were present in her system, i.e. cocaine, opiates, amphetamines, and even THC. Traces of her prescriptions—Lamotrigine, Quetiapine, Venlafaxine, and Bupropion (Wellbutrin)—were identified but the quantity was not sufficient to make a proportional analysis.

It was the pill count in Elisa’s room that was telling. She’d had her prescriptions refilled in Vancouver on January 11, 2013, and what remained was a leading indicator as to what might have triggered a psychotic episode that led Elisa to willingly crawl inside a water tank.

Lamotrigine (anti-seizure meds) 60 issued 70 remaining

Quetiapine (bipolar/mood meds) 30 issued 20 remaining

Venlafaxine (anti-depression meds) 60 issued 64 remaining

Wellbutrin (anti-depression meds) 60 issued 57 remaining

The autopsy report’s conclusion is careful about speaking to Elisa’s undermedication:

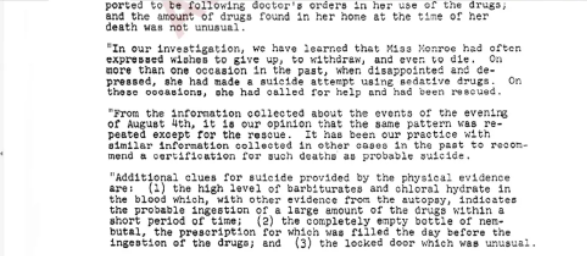

Opinion: The decedent died as a result of drowning. A complete autopsy examination showed no evidence of trauma, and toxicology studies did not show acute drug or alcohol intoxication. Decedent had a history of bipolar disorder for which she was prescribed medication. Toxicology studies were performed for the presence of these drugs. However, quantitation in the blood was not performed due to the limited sample availability. Therefore, interpretation is limited. Police investigation did not show evidence of foul play. A full review of the circumstances of the case and appropriate consultation do not support intent to harm oneself. The manner of death is classified as accident.

Something to note in the autopsy report is Elisa’s death classification was listed as Undertermined upon conclusion of her physical examination on February 21. On June 18, the classification was changed to Accident. This was after the tox results came back and there was no sign of any overdose or poisoning. There is nothing to read into the change—this is routine to change a conclusion upon receiving further evidence or absence of evidence.

Despite internet sleuths pontificating about conspiracy theories from a serial killer loose in the hotel to a poltergeist practicing the paranormal, it’s clear from the official investigation that Elisa went into some sort of psychotic event and intentionally—on her own—entered the insecure, water-filled cistern. With no way out and only treading water to temporarily survive, she succumbed to drowning. It must have been a ghastly way to go.

The Cecil Hotel

In reading up on the Cecil Hotel’s history, I found quotes like these describing its past:

“Insanity within its walls. A hotbed of death.”

“Insanity within its walls. A hotbed of death.”

“Guests ranging from drug dealers to prostitutes to rapists.”

“A lot of safety issues. Thousands of 911 calls to there, normally three a day.”

“If you didn’t watch yourself, you might be flying out the window without wings.”

“The most infamous building in horror lore.”

“Unparalleled reputation for the macabre.”

“A meeting place for junkies, runaways, and criminals where they played in violence and death.”

“Murders, and suicides, and unexplained paranormal events.”

“The most dangerous place in Los Angeles, especially above the seventh floor.”

“A place where serial killers go to let their hair down.”

Yes, serial killers.

At the height of his spree, Night Stalker Richard Ramirez stayed on The Cecil’s top floor. Staff and residents would see Ramirez stash his bloodied clothing in the hotel’s trash receptacle and then walk through the lobby in his underwear or sometimes naked. No one reported Ramirez because, back then, who was to say what was normal or abnormal at the Cecil Hotel.

Another Cecil resident serial killer, although less known than the Night Stalker, was Jack Unterweger. He had a different distinguishment, though. Unterweger was an international serial killer who started his murderous career in Austria before moving shop to LA. His MO was to pick up prostitutes and strangle them with their own bras.

Getting back to The Cecil’s history. It was built in the Roaring Twenties as a luxury, but affordable, hotel. Centrally located in the Skid Row area of Los Angeles, The Cecil was perfectly positioned to suffer decline in the Great Depression then dilapidate into a festered urban sore through the later part of the twentieth century and into the early 2000s.

Getting back to The Cecil’s history. It was built in the Roaring Twenties as a luxury, but affordable, hotel. Centrally located in the Skid Row area of Los Angeles, The Cecil was perfectly positioned to suffer decline in the Great Depression then dilapidate into a festered urban sore through the later part of the twentieth century and into the early 2000s.

Just a side note on Skid Row. Skid Row is now an urban language term for any rundown part of a city where rubbies reside. LA’s Skid Row is an officially-listed civic region just like SoHo is in Manhattan or the French Quarter is in New Orleans. But LA’s Skid Row set the gold standard for a pit of poverty that made the Skid Row term a household name for the destitute and down-in-the-dumps. At one time, approximately 10,000 homeless people occupied a 4-mile radius around The Cecil.

By 2013, when Elisa Lam died at The Cecil, the hotel had improved. It was renamed, rebranded you could say, into the Stay on Main and billed as an affordable housing complex. Despite renovations and staff improvements, the Cecil Hotel remained lacking on one vital level.

Safety.

And this is where the stories of Elisa Lam’s death and the Cecil Hotel’s history merge.

I’m sure Elisa Lam chose the Stay on Main (the old Cecil Hotel) because of the location and the price. Can’t argue with that logic when you’re a traveling youth. But other things were going on in Elisa’s life which, to me, seem typical of a bipolar person experiencing their manic and adventuresome stage. That’s reducing or quitting their meds because they don’t think they feel the need at the time.

You can see in watching the now-famous Elevator Video that Elisa was in mental distress. She appeared paranoid, as if someone was out there wanting to harm her. It’s a classic case of psychosis. Somehow from the elevator Elisa made her way to the roof and the tank where she died.

Here’s where the hotel part enters. Elisa had to pass through two barriers to experience her demise. First—getting onto the roof. Second—getting into the tank. Both points should have been locked barriers and impossible for a young lady like Elisa to penetrate.

I’m not sure about the roof access method. I’ve been in a lot of hotels over the years, and I’ve never noticed one that has a public elevator portal to the roof. P for Parkade, yes, but not R for Roof on the buttons. She must have taken the stairway and that, in any case, should have been locked and not accessible with her room key card that was found in the death tank.

The Death Tank

The United States Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) clearly defines the cistern or water tank on top of the hotel a “Confined Space”. OSHA has extremely strict rules regulating entry into confined spaces where a person could be trapped and killed. OSHA takes confined space entry so seriously that, not only does a confined space have to be clearly signed and sufficiently locked, OSHA requires a written permit for a worker to enter. That permit must outline the purpose and method of entry and also a rescue plan if things go bad.

In utter basic, OSHA deals with common sense safety procedures like preventing access to dangerous places. For example, a 14-story hotel roof and a potentially lethal water cistern. The Cecil Hotel (sorry, in 2013 the Stay on Main) was utterly negligent in allowing a psychotic young lady to get onto its roof and drown in their tank.

Both access points should have had locked barriers, and Elisa’s host failed to protect their guest’s safety. But I guess preventing things like Elisa Lam’s ghastly death at the haunted Cecil Hotel has never been part of the company culture.

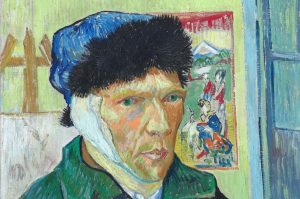

Most people know the story of Vincent Van Gogh’s ear. It’s a true story, but the truth is he only cut part of his left ear off with a razor during a difficult episode with his on-again, off-again relationship with painter Paul Gauguin. The story goes on that Van Gogh gave his ear piece to a brothel lady, then he bandaged himself up and painted one of many self-portraits. I just looked at this portrait (Google makes Dutch Master shopping easy) and was struck by the image of his right side being bandaged. Then I realized Van Gogh painted selfies by looking in a mirror.

Most people know the story of Vincent Van Gogh’s ear. It’s a true story, but the truth is he only cut part of his left ear off with a razor during a difficult episode with his on-again, off-again relationship with painter Paul Gauguin. The story goes on that Van Gogh gave his ear piece to a brothel lady, then he bandaged himself up and painted one of many self-portraits. I just looked at this portrait (Google makes Dutch Master shopping easy) and was struck by the image of his right side being bandaged. Then I realized Van Gogh painted selfies by looking in a mirror. Vincent Van Gogh’s spirit left this world at 1:30 a.m. on July 29. He passed without medical intervention on his bed, and the medical cause was, most likely, exsanguination or internal bleeding. There was no autopsy, and Van Gogh was buried in a nearby churchyard the next day.

Vincent Van Gogh’s spirit left this world at 1:30 a.m. on July 29. He passed without medical intervention on his bed, and the medical cause was, most likely, exsanguination or internal bleeding. There was no autopsy, and Van Gogh was buried in a nearby churchyard the next day.

Other people weren’t. In 2011, two researchers took a good and hard look into Van Gogh’s life and death. They had full access to the Van Gogh Museum’s archives in Amsterdam and spent enormous time reviewing original material. They found a few things.

Other people weren’t. In 2011, two researchers took a good and hard look into Van Gogh’s life and death. They had full access to the Van Gogh Museum’s archives in Amsterdam and spent enormous time reviewing original material. They found a few things. Researchers Naifeh and Smith also took a deep dive into what they could find on Rene Secretan’s background. They painted him as a big kid—a thug and a bully who was well known to have picked on wimpy Van Gogh throughout the month of July 1890. Secretan came from a wealthy Paris family who summered at Auvers with their second home within walking distance of Van Gogh’s rooming house.

Researchers Naifeh and Smith also took a deep dive into what they could find on Rene Secretan’s background. They painted him as a big kid—a thug and a bully who was well known to have picked on wimpy Van Gogh throughout the month of July 1890. Secretan came from a wealthy Paris family who summered at Auvers with their second home within walking distance of Van Gogh’s rooming house.

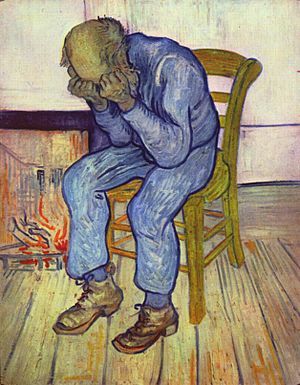

If I were the coroner ruling on Vincent Van Gogh’s death, I’d readily concur the cause of death was slow exsanguination resulting from a single gunshot wound to the abdomen. I’d have a harder time with the classification. Here, I’d have to use a process of elimination from the five categories—natural, homicide, accidental, suicide, or undetermined.

If I were the coroner ruling on Vincent Van Gogh’s death, I’d readily concur the cause of death was slow exsanguination resulting from a single gunshot wound to the abdomen. I’d have a harder time with the classification. Here, I’d have to use a process of elimination from the five categories—natural, homicide, accidental, suicide, or undetermined.