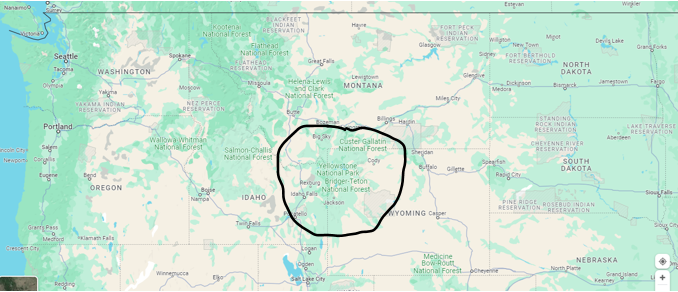

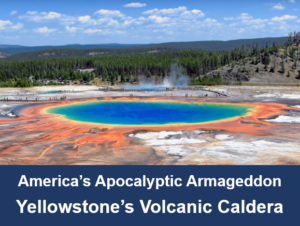

Every year, more than 3 million tourists visit Yellowstone National Park which covers 3,472 square miles in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho. Wildlife abounds, and the sheer, breathtaking natural beauty is beyond compare. But as camera-armed seniors photograph mudpots, fumaroles, and their grandkids rabbit-earing each other with Old Faithful in the backdrop, most are oblivious to standing on top of an active supermassive volcanic caldera—1,204 square miles in size—that’s set to blow with possibly more explosive power than all the atomic weapons in the US nuclear arsenal combined.

Every year, more than 3 million tourists visit Yellowstone National Park which covers 3,472 square miles in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho. Wildlife abounds, and the sheer, breathtaking natural beauty is beyond compare. But as camera-armed seniors photograph mudpots, fumaroles, and their grandkids rabbit-earing each other with Old Faithful in the backdrop, most are oblivious to standing on top of an active supermassive volcanic caldera—1,204 square miles in size—that’s set to blow with possibly more explosive power than all the atomic weapons in the US nuclear arsenal combined.

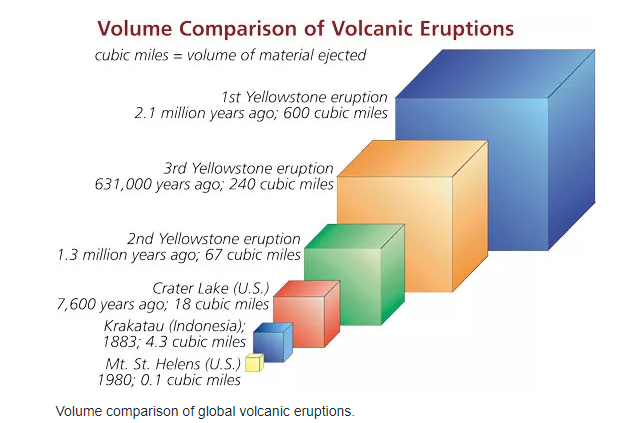

This won’t be the first volcanic rodeo for Yellowstone. It’s performed three times in the past. One eruption was the second largest in geological history that made the 1980 Mount St. Helens blast in Washington State seem meeker than a microbe’s fart.

There’s no question Yellowstone will boom once again. It’s just a matter of when. And when it does, it’ll be America’s Apocalyptic Armageddon—probably killing 10 million people in no time flat and slowly suffocating the rest of the country with lung-searing ash.

But before we go all Doomsday on this, let’s visit Yellowstone Park, meet its resident volcano, and decide what to make out of all this fear.

Yellowstone’s region has had human inhabitants for 10,000 years. Indigenous people hunted game, gathered plants, quarried obsidian for tools, and used the thermal vents for religious and medicinal purposes. Today, the National Park Service recognizes 27 tribes as holding traditional titles.

The first Europeans were hardy explorers, trappers, and hunters who brought back to the east fantastic tales of extraordinary sights—kaleidoscope colors of whirling hot pools that hissed while they bubbled, spouting geysers that marked time with the clock, and the ground too hot to step on without thick-soled boots. The Establishment, at the time, cast doubt on these claims and sent official expeditions to Yellowstone to see for themselves.

Sure enough, these claims were true. On March 1, 1872, United States President Ulysses S. Grant signed into law the first American National Park. Yellowstone. The land was preserved in its natural form forever. Since then, 63 more U.S. national parks have been created covering 52.2 million pristine acres.

Yellowstone is the largest hydrothermal ecosystem on Earth. It has over 10,000 unique thermal features, one of which is Old Faithful. Yellowstone also has the largest concentration of wildlife in America including a shaggy old bison herd that’s thrived there since prehistoric times.

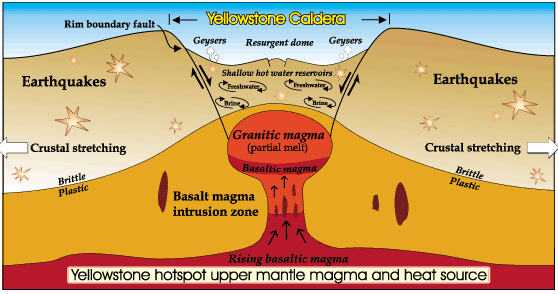

At the heart of Yellowstone’s ecology, or should it be said its belly, is a massive magma chamber. Magma is the scientific term for molten rock that’s hot beyond comprehension. It’s the stuff that heats the geysers, whirls the pools, and boils the mud.

Here’s a quote from the U.S. Geological Survey Department:

Yellowstone is underlain by two magma bodies. The shallower one is composed of rhyolite (a high-silica rock type) and stretches from 5 km to about 17 km (3 to 10 mi) beneath the surface and is about 90 km (55 mi) long and about 40 km (25 mi) wide. The chamber is mostly solid, with only about 5-15% melt. The deeper reservoir is composed of basalt (a low-silica rock type) and extends from 20 to 50 km (12 to 30 mi) beneath the surface. Even though the deeper chamber is about 4.5 times larger than the shallow chamber, it contains only about 2% melt.

The method that scientists use to discern this information is similar to medical CT scans that bounce X-rays through the human body to make three-dimensional pictures of internal tissue. In an analogous manner, a method called seismic tomography uses hundreds to thousands of earthquakes recorded by dozens of stations to measure the speed of seismic waves through the Earth–data that allow geophysicists to make three-dimensional pictures of structures beneath the surface. Scientists compare these seismic velocities and infer the composition by comparing them with average, thermally undisturbed values.

And here’s more information from the Yellowstone National Park Service:

Magma (molten rock from below the earth’s crust) is close to the surface in the greater Yellowstone area. This shallow body of magma is caused by heat convection in the mantle. Plumes of magma rise through the mantle, melting rocks in the crust, and creating magma reservoirs of partially molten, partially solid rock.

Mantle plumes transport heat from deep in the mantle to the crust and create what we call “hot spot” volcanism. Hot spots leave a trail of volcanic activity as tectonic plates drift over them. As the North American Plate drifted westward over the last 16.5 million years, the hot spot that now resides under the greater Yellowstone area left a swath of volcanic deposits across Idaho’s Snake River Plain.

Heat from the mantle plume has melted rocks in the crust and created two magma chambers of partially molten, partially solid rock near Yellowstone’s surface. Heat from the shallowest magma chamber caused an area of the crust above it to expand and rise. Stress on the overlying crust resulted in increased earthquake activity along newly formed faults.

Eventually, these faults reached the magma chamber and magma oozed through the cracks. Escaping magma released pressure within the chamber, which also allowed volcanic gasses to escape and expand explosively in a massive volcanic eruption. The eruption spewed copious volcanic ash and gas into the atmosphere and produced fast, super-hot debris flows (pyroclastic flows) over the existing landscape. As the underground magma chamber emptied, the ground above it collapsed and created the first of Yellowstone’s three calderas.

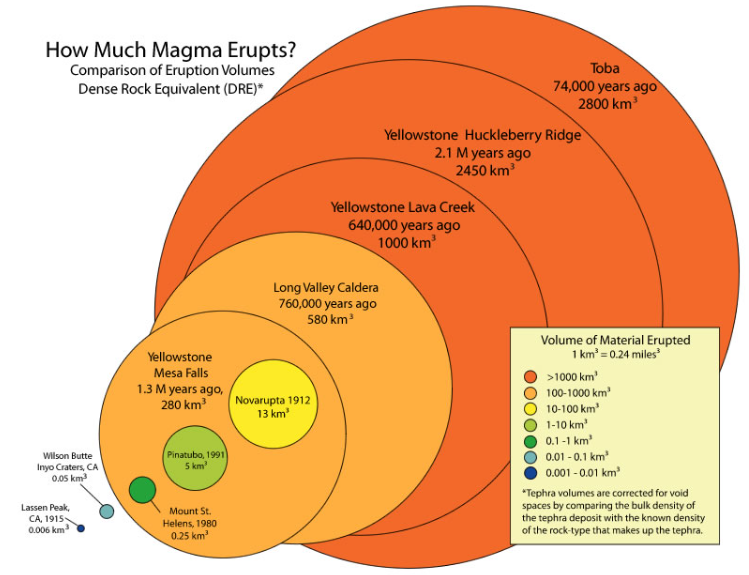

This eruption 2.1 million years ago—among the largest volcanic eruptions known to man—coated 5,790 square miles with ash, as far away as Missouri. The total volcanic material ejected is estimated to have been 6,000 times the volume of material ejected during the 1980 eruption of Mt. St. Helens, in Washington.

A second significant, though smaller, volcanic eruption occurred within the western edge of the first caldera approximately 1.3 million years ago. The third and most recent massive volcanic eruption 631,000 years ago created the present 30- by 45-mile-wide Yellowstone Caldera. Since then, 80 smaller eruptions have occurred. Approximately 174,000 years ago, one of these created what is now the West Thumb of Yellowstone Lake.

During and after these explosive eruptions huge lava flows of viscous rhyolitic lava and less voluminous basalt lava flows partially filled the caldera floor and surrounding terrain. The youngest of these lava flows is the 70,000-year-old Pitchstone rhyolite flow in the southwest corner of Yellowstone National Park.

Since the last of three caldera-forming eruptions, pressure from the shallow magma body has formed two resurgent domes inside the Yellowstone Caldera. Magma may be as little as 3–8 miles beneath Sour Creek Dome and 8–12 miles beneath Mallard Lake Dome, and both domes inflate and subside as the volume of magma or hydrothermal fluids changes beneath them. The entire caldera floor lifts up or subsides, too, but not as much as the two domes.

In the past century, the net inflation has tilted the caldera floor toward the south. As a result, Yellowstone Lake’s southern shores have subsided and trees now stand in water, and the north end of the lake has risen into a sandy beach at Fishing Bridge.

Recent Activity

Remarkable ground deformation has been documented along the central axis of the caldera between Old Faithful and White Lake in Pelican Valley in historic time. Surveys of suspected ground deformation began in 1975 using vertical-motion surveys of benchmarks in the ground. By 1985 the surveys documented unprecedented uplift of the entire caldera in excess of a meter (3 ft).

Later GPS measurements revealed that the caldera went into an episode of subsidence (sinking) until 2005 when the caldera returned to an episode of extreme uplift. The largest vertical movement was recorded at the White Lake GPS station, inside the caldera’s eastern rim, where the total uplift from 2004 to 2010 was about 27 centimeters (10.6 in).

The rate of rise slowed in 2008 and the caldera began to subside again during the first half of 2010. The uplift is believed to be caused by the movement of deep hydrothermal fluids or molten rock into the shallow crustal magma system at a depth of about 10 km beneath the surface. A caldera may undergo episodes of uplift and subsidence for thousands of years without erupting.

Notably, changes in uplift and subsidence have been correlated with increases of earthquake activity. Lateral discharge of these fluids away from the caldera, and the accompanying earthquakes, subsidence, and uplift relieves pressure and could act as a natural pressure release valve balancing magma recharge and keeping Yellowstone safe from volcanic eruptions.

That was informative. But what the National Park Service and the Geological Survey quotes don’t address is how they measure the size of a volcanic blast. It’s called the Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI). While we’re quoting, here’s another quote:

The volcanic explosivity index (VEI) is a relative measure of the explosiveness of volcanic eruptions. It was devised by Christopher G. Newhall of the United States Geological Survey and Stephen Self in 1982.

Volume of products, eruption cloud height, and qualitative observations (using terms ranging from “gentle” to “mega-colossal”) are used to determine the explosivity value. The scale is open-ended with the largest eruptions in history given a magnitude of 8. A value of 0 is given for non-explosive eruptions, defined as less than 10,000 m3 (350,000 cu ft) of tephra ejected; and 8 representing a mega-colossal explosive eruption that can eject 1.0×1012 m3 (240 cubic miles) of tephra and have a cloud column height of over 20 km (66,000 ft). The scale is logarithmic, with each interval on the scale representing a tenfold increase in observed ejecta criteria, with the exception of between VEI-0, VEI-1 and VEI-2.

Classification

With indices running from 0 to 8, the VEI associated with an eruption is dependent on how much volcanic material is thrown out, to what height, and how long the eruption lasts. The scale is logarithmic from VEI-2 and up; an increase of 1 index indicates an eruption that is 10 times as powerful. As such, there is a discontinuity in the definition of the VEI between indices 1 and 2. The lower border of the volume of ejecta jumps by a factor of one hundred, from 10,000 to 1,000,000 m3 (350,000 to 35,310,000 cu ft), while the factor is ten between all higher indices. In the following table, the frequency of each VEI indicates the approximate frequency of new eruptions of that VEI or higher.

About 40 eruptions of VEI-8 magnitude within the last 132 million years (Mya) have been identified, of which 30 occurred in the past 36 million years. Considering the estimated frequency is on the order of once in 50,000 years,[3] there are likely many such eruptions in the last 132 Mya that are not yet known. Based on incomplete statistics, other authors assume that at least 60 VEI-8 eruptions have been identified The most recent is Lake Taupō’s Oruanui eruption, more than 27,000 years ago, which means that there have not been any Holocene eruptions with a VEI of 8.

There have been at least 10 eruptions of VEI-7 in the last 11,700 years. There are also 58 Plinian eruptions, and 13 caldera-forming eruptions, of large, but unknown magnitudes. By 2010, the Global Volcanism Program of the Smithsonian Institution had cataloged the assignment of a VEI for 7,742 volcanic eruptions that occurred during the Holocene (the last 11,700 years) which account for about 75% of the total known eruptions during the Holocene. Of these 7,742 eruptions, about 49% have a VEI of 2 or lower, and 90% have a VEI of 3 or lower.

Limitations

Under the VEI, ash, lava, lava bombs, and ignimbrite are all treated alike. Density and vesicularity (gas bubbling) of the volcanic products in question is not taken into account. In contrast, the DRE (dense-rock equivalent) is sometimes calculated to give the actual amount of magma erupted. Another weakness of the VEI is that it does not take into account the power output of an eruption, which makes the VEI extremely difficult to determine with prehistoric or unobserved eruptions.

Although VEI is quite suitable for classifying the explosive magnitude of eruptions, the index is not as significant as sulfur dioxide emissions in quantifying their atmospheric and climatic impact.

Now let’s look at supermassive volcanos from around the world and their VEI ratings.

- Hunga Ha’apai — Tonga, 2022 VEI 5.7

- Huaynaputina — Peru, 1600 VEI 6

- Krakatoa — Indonesia, 1883 VEI 6

- Santa Maria — Guatemala, 1902 VEI 6

- Novarupta — Alaska, 1912 VEI 6

- Pinatuba — Philippines, 1991 VEI 6

- Ambrym Island, Vanuatu, AD50 VEI 6+

- Ilopango — El Salvador, AD431 VEI 6+

- Mount Thera — Greece, BC1610 VEI 7

- Changbaishan — China AD1000 VEI 7

- Mount Tambora — Indonesia 1815 VEI 7

- Yellowstone — USA BC2.1Ma VEI 8

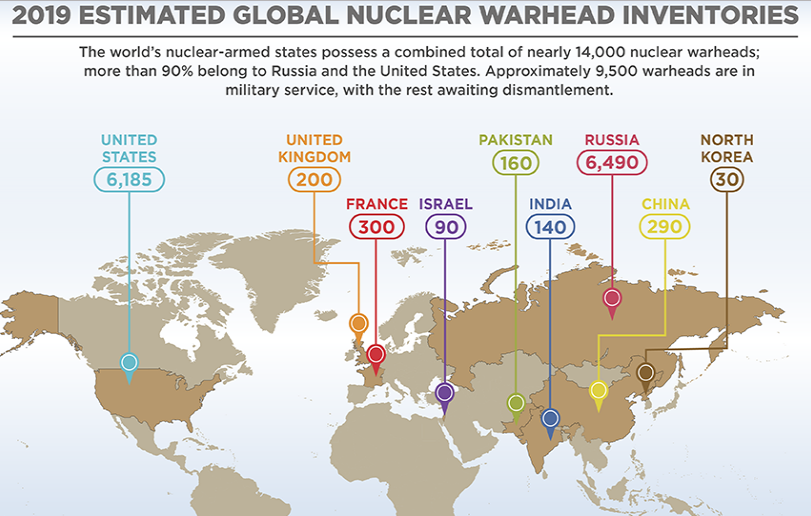

So, the potential of a Level 8 eruption if Yellowstone loses its stuff? What would that look like from a realistic point? The release of energy and matter from a magna pile big enough to fill 11 Grand Canyons, according to the U.S. Geological Survey?

Well, the best source to describe that is the USGS itself. And they did so in an extensive report along with a detailed hazard response plan. Extrapolating from these and other credible sources, the most likely outfall from a VEI 8 explosion is this:

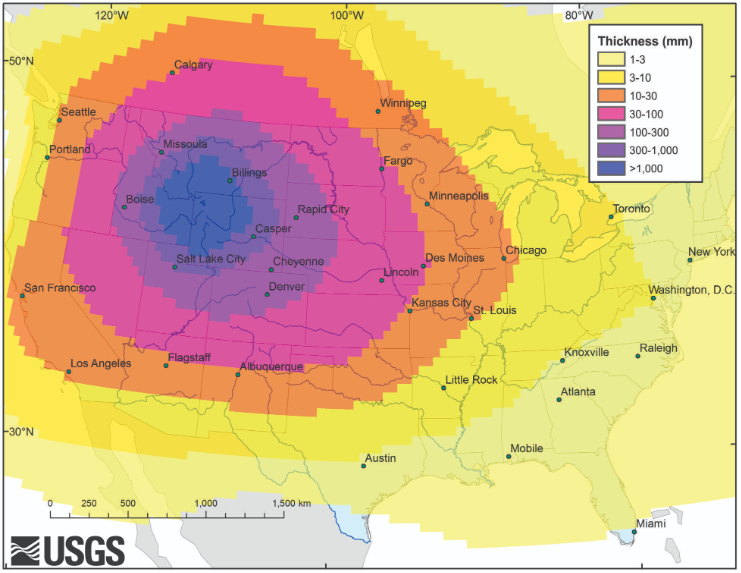

The blast would emit over 4,800 cubic miles (20,000 cubic kilometers) of ash and glass shards. A radius of 700 miles would be covered with three feet of debris. That would include Montana, Wyoming, Idaho, Utah, and parts of southwest Canada. Cities like Denver, Spokane, Salt Lake City, Boise, Billings, Cheyenne, and Rapid City would be obliterated. Approximately 10 million people would be dead, with millions more perishing in the wake.

The 100,000-foot-high ash cloud would move primarily eastward with the prevailing winds, eventually reaching the Beltway and as far south as Miami. Commercial air traffic over North America would stop and, shortly, so would most airspace in the world. Road and rail transport in the continental United States would grind to a halt, and the supply chain would be crippled beyond belief. Food and fuel sources would be scarce, and the next round of crops wouldn’t have a chance as meaningful photosynthesis would be blocked by the ash which could take years—perhaps a decade or more—to filter out.

Medical aid would be nearly impossible for the millions and millions exposed to volcanic ash which forms a cement-like coat on the inside of the lungs. The global climate could cool by 12 degrees leaving almost all Americans in an apocalyptic freeze. It’s a scenario almost too horrid to envision.

Yellowstone is certain to erupt again. It’s just a matter of time. When? Folks at the USGS don’t think it’s anywhere in the foreseeable future. It was 800,000 years between the first and second explosions, then another 636,000 years to the third. And it’s been 664,000 years since Yellowstone’s last big sneeze and today, doing the math, that’s an average eruption every 718,000 years. So, we have another 54,000 years yet to go till we’re on target.

Still, 54 millennia don’t keep some from getting excited and their stories from going viral. In early 2014, one of Yellowstone’s seismic monitors called B944 went haywire and began broadcasting erroneous, actually crazy, data on a public viewer. It got picked up by a website called End Times Forecaster that calculated through Biblical algorithms and the Friday Crescent Moon Death Day Cycle that Armageddon would strike on March 28, 2014. Using the Batman Map Strike Zone (don’t ask) they pinpointed the epicenter of destruction right smack dab in the middle of Yellowstone Lake.

Now this may sound like a load of tinfoil crapped on a parent’s-basement-dweller’s head by a diarrhetic seagull, but don’t laugh. On March 30, 2014, a 4.8 magnitude earthquake—its epicenter at Yellowstone Lake—shook the entire park. It was the largest Yellowstone quake in the previous 34 years.

So, setting aside feeds from the Bunker Report and, instead, relying on solid USGS scientific data, I’d say it’s perfectly safe to take the grandkids on a Yellowstone vacation next summer. You won’t have to sacrifice them to appease the angry volcano. Just make sure they don’t pet the fluffy cows.