Treasure. The very word is intriguing, invigorating, and—to some—even intoxifying. There’s something magical about lost treasure whether sunken, hidden, or buried beneath the earth in a clandestine location. Such is the lure of Captain Kidd, the infamous pirate, whose hoard of richness may still be out there, stashed in some secret site and silently awaiting discovery.

Treasure. The very word is intriguing, invigorating, and—to some—even intoxifying. There’s something magical about lost treasure whether sunken, hidden, or buried beneath the earth in a clandestine location. Such is the lure of Captain Kidd, the infamous pirate, whose hoard of richness may still be out there, stashed in some secret site and silently awaiting discovery.

There’s no doubt Captain William Kidd buried some treasure. That’s an indisputable fact, as his chests containing gold, silver, and a few emeralds were dug up on Gardiners Island in now-New York State in 1699. Kidd’s treasure was inventoried, forfeited to the British Crown, and entered as evidence during his trial for murder and piracy. Captain Kidd was convicted and hung in 1701. Then, his body was garroted and suspended in public display as a warning to other pirates.

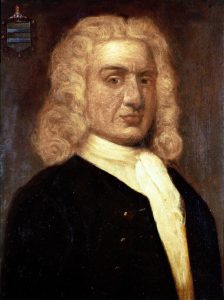

By all accounts, William Kidd was not your typical pirate. Kidd wasn’t a swashbuckling Johnny Depp—Jack Sparrow character, nor was he a homicidal psychopath like Blackbeard or Black Bart. No, Captain Kidd was a gentleman of high status who got sucked into the job by the British King and got screwed in the end. You could say Kidd got royally shafted.

By all accounts, William Kidd was not your typical pirate. Kidd wasn’t a swashbuckling Johnny Depp—Jack Sparrow character, nor was he a homicidal psychopath like Blackbeard or Black Bart. No, Captain Kidd was a gentleman of high status who got sucked into the job by the British King and got screwed in the end. You could say Kidd got royally shafted.

Captain Kidd is long dead. But the legend of his remaining treasure lives on, and there may be some real truth to folklore that the bulk of Kidd’s bounty was never seized by authorities. Are Kidd’s real valuables—precious gems, coins, ivory, opium, and ornaments—buried somewhere and lost in time? Let’s look at who Captain Kidd truly was and the highly-suspicious circumstances that led to his easily-convertible, common commodities of gold and silver being found for the Crown while priceless pieces somehow disappeared.

——

William Kidd was a Scotsman. He was born in 1655 to a seafaring family. From the time Kidd was a kid and could put on boots and a slicker, he was onboard sailing ships that crossed the Atlantic. William Kidd received a Captain position within the British merchant marine. He was not a Navy man, but he was well-skilled with navigation and vessel armaments. This was the historical period when piracy ruled the Seven Seas, and civilian vessels needed all the protection they could get.

Captain Kidd relocated to New York City around 1690. He had given service to England’s King George III as a “privateer” commissioned to hunt down “buccaneers” and “pirates”. Kidd did an admirable job. He seemed to be in the King’s favor when he returned to normal life and married a wealthy American socialite.

Kidd temporarily boxed-up his sexton and settled into land-based businesses. However, King George III had different designs for William Kidd’s seagoing talents. Several events were going on where the King needed civilian help in the naval department. England was at war with France and Spain. As well, the age of piracy was at its peak, and the King wanted to take advantage of the situation.

Kidd temporarily boxed-up his sexton and settled into land-based businesses. However, King George III had different designs for William Kidd’s seagoing talents. Several events were going on where the King needed civilian help in the naval department. England was at war with France and Spain. As well, the age of piracy was at its peak, and the King wanted to take advantage of the situation.

Here’s where William Kidd came in. The British Lords decreed (with the King’s royal assent) that all goods aboard French, Spanish, and pirate vessels could be commandeered for the financial benefit of the Crown. It was a strategic way of paying for war costs and subduing the enemy at the same time.

One of the British Admiralty’s tactics was to commission or charter civilians like Kidd to “privateer” and profit-share spoils with the uppers. A privateer, by definition, is “a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war”. Buccaneers are basically unsanctioned privateers, while pirates are common thieves on the water.

Through the King, a group of nobles enlisted Captain Kidd’s privateer services in a way he couldn’t say no. As a man with Kidd’s social status, it would appear disloyal to refuse a royal request. Kidd acquiesced his commander and returned to England in 1696 where he received a Letter of Marque authorizing him to set forth and prey on French, Spanish, and pirate property.

The deal was sealed. Kidd’s role was to collect and share spoils with his financiers—noble Whig Lords, Earls, and Knights before which 10 percent was skimmed by the King. The arrangement was still profitable for Kidd and his crew, provided they could locate plunderable targets. That proved problematic.

Things started bad and went worse for Captain Kidd. He weighed anchor in September 1696 in the Adventure Galley, a 284-ton hybrid ship equipped with sails and oars as well as 34 cannons. Kidd had hand-selected his crew of 150 and felt confident as he headed down the Thames for the Cape of Good Hope and hunting off the coast of Madagascar.

Things started bad and went worse for Captain Kidd. He weighed anchor in September 1696 in the Adventure Galley, a 284-ton hybrid ship equipped with sails and oars as well as 34 cannons. Kidd had hand-selected his crew of 150 and felt confident as he headed down the Thames for the Cape of Good Hope and hunting off the coast of Madagascar.

Still on the Thames, Kidd’s Adventure Galley passed a British Naval frigate whose commander knew not of Kidd’s mission. Kidd failed to offer a courtesy salute which offended the Naval Commander who heaved-to the Adventure Galley and summarily pressed one-third of Kidd’s men into naval service. Kidd changed course for America where, in New York, he hired replacements.

Kidd’s replacement crew was not from the cut-above. Rather, the available stock were criminals and societal rejects who the Governor of New York was glad to see go. Other fine sailors abandoned ship in New York because the Adventure Galley was a poorly and hastily-built piece of shit that leaked like a sieve and steered like a stone.

“Many flocked to Kidd from all parts. Men of desperate fortunes and necessities, in expectation of getting vast treasure. It is generally believed here that if he (Kidd) misses the design named in his commission, he will not be able to govern such a villainous herd.” ~ Governor Fletcher of New York Colony.

But Captain Kidd was no quitter. He accepted a bag of rag tags and set forth on his chartered commission. Before Kidd reached the Cape, a cholera outbreak plagued the ship and another third of his compliment perished. Now Captain Kidd was at a distinct disadvantage at controlling the crew and murmurs of mutiny floated about.

Kidd had no luck at all. Not only was his crew a band of devious deviants, much like the cutthroats of lore, Kidd’s officers were also disloyal. William Kidd commanded his ship according to the rules of maritime law and legal engagement. Pirate hunting was poor in the Indian Ocean as was locating valid targets sailing under French and Spanish flags. Kidd refused to engage ships under Dutch registration or anything that resembled a British subject.

Kidd had no luck at all. Not only was his crew a band of devious deviants, much like the cutthroats of lore, Kidd’s officers were also disloyal. William Kidd commanded his ship according to the rules of maritime law and legal engagement. Pirate hunting was poor in the Indian Ocean as was locating valid targets sailing under French and Spanish flags. Kidd refused to engage ships under Dutch registration or anything that resembled a British subject.

A year passed. Kidd’s charge had no income and little left to pay or outfit his men. Open revolt was on deck and led to violence on October 30, 1697, when Captain Kidd and gunner William Moore got into a fight. Kidd hit Moore on the head with an iron-strapped bucket, and Moore died the next day of a brain injury.

Word of Kidd’s poor performance got back to the Whig backers. They were displeased and began undermining Kidd’s credibility. Rumors that Kidd may have gone rogue and turned from privateer to pirate circulated through dispatches distributed through the British colonies and far-reaching colonial interests.

Kidd, however, knew or did anything of the sort. He was simply a victim of changing times when France and Spain were tiring of war and their interests in the Indian Ocean dried up. The pirates, once finding less and less loot, left the area and returned to plunder the Caribbean.

On January 30, 1698, Captain Kidd and the Adventure Galley finally found a victim. It was the 400-ton Quedagh Merchant which was Armenian registered and French flagged. The ship was bound from Bengal to Surat in India, and Kidd engaged it near Kochi on the southwest tip of the subcontinent.

On January 30, 1698, Captain Kidd and the Adventure Galley finally found a victim. It was the 400-ton Quedagh Merchant which was Armenian registered and French flagged. The ship was bound from Bengal to Surat in India, and Kidd engaged it near Kochi on the southwest tip of the subcontinent.

The engagement was peaceful. The Quedagh Merchant’s captain was an Englishman employed by a Dutch firm and crew operating for India’s Grand Mughal. The ship had a written pass from the French East India Company and all was in good order. The Quedagh Merchant was also loaded with highly-prized valuables—silk bales, opium chests, satin fabrics, muslins, sugar, tobacco, and tea. In its hold was a mass of gold, silver, and gemstones along with jeweled and ornate artifacts fit for the Mughal.

Captain Kidd was in a quandary, for sure. On one hand, Kidd viewed the Quedagh Merchant as a non-viable engagement. It was not a pirate ship by any standards and belonged to an entity not in conflict with British rule. On the other hand, this was the first chance Kidd’s crew had at getting paid, and they threatened to cut Kidd adrift if he didn’t seize the ship and its contents.

Kidd succumbed to his crew. He justified that the Quedagh Merchant was French authorized under the pass and set forth to commandeer the vessel with a privateer claim for the British Crown. This pissed off the Indian Grand Mughal to no end. His goods were now gone, and he loudly complained to the British High Commission that, in turn, reported back to the King.

Captain Kidd was a practical man as well as a competent sailor. Rather than transfer goods to the leaky Adventure Galley, he made port in Kochi, dismissed the Dutch crew, and made off with their Quedagh Merchant. Kidd renamed it the Adventure Prize and set sail for the Caribbean’s West Indies.

Kidd and his converted merchant vessel stopped in Madagascar in April 1698. Here, more of Kidd’s crew jumped ship and joined a pirate venture captained by Robert Culliford who was a notorious man and a long foe of Captain Kidd. Port tensions rand high, so Kidd slipped away on the newly-named and treasure-laden Adventure Prize.

He arrived at Catalina Island off the south side of the Dominican Republic in late 1698. Here, Kidd anchored in a secluded lagoon and made arrangements for a smaller vessel, a sloop, to take him with a select small crew to New York to bargain with the British Crown. Captain Kidd was now well aware of the piracy accusations levied against him.

Massachusetts Governor Bellomont was Kidd’s long-time acquaintance who Kidd thought he could trust. T’wasn’t so. Kidd was a wary sort, so he took treasures from the Quedagh Merchant’s cargo that could be easily converted into negotiable currency—gold, silver, gems, and elaborate jewelry and ornaments. This was Kidd’s insurance policy—his bargaining chips—that he held for safekeeping.

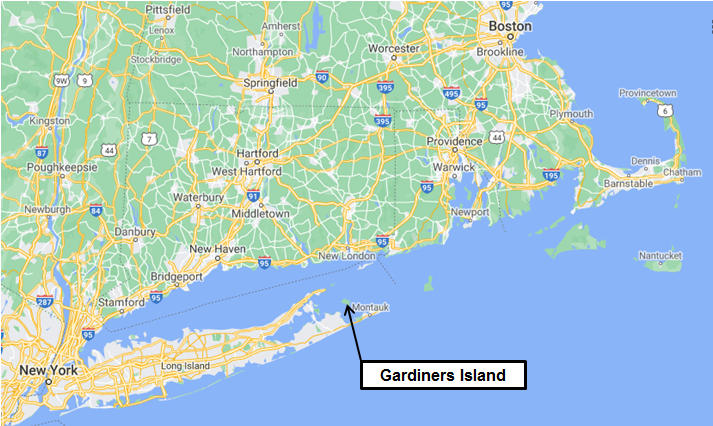

Kidd cautiously approached the American Atlantic coast in June 1699. He was well-familiar with the region and many New York area inhabitants. That included the Lion Gardiner family and their private 3,318-acre island rightfully called Gardiners Island situated at the northeast tip of Long Island.

Here, Captain William Kidd arranged with the Gardiners to offload treasure and bury it on Gardiners Island. Exactly what was buried or how many burial spots Kidd used remain unknown. This is where the legend of Captain Kidd’s lost treasure began.

Captain Kidd sent a lawyer-delivered letter to Governor Bellomont in Boston stating he was back and ready to negotiate a pardon for piracy accusations against him. Throughout Kidd’s time on this three-year privateer voyage, he firmly believed he was acting according to his royal Commission and his noble backers would soundly support him.

Kidd was wrong. Politics changed during his absence, and the new Torrie powerbrokers in England planned to use Kidd as a pawn to help impeach his Whig patrons. Even the King turned on William Kidd. Governor Bellomont replied with a letter to Kidd stating:

“I have advised with His Majesty’s Council and showed them your letter, and they are of the opinion that, if you can be so clear as you said, then you may safely come hither. And I make no manner of doubt but to obtain the King’s pardon for you and those few men you have left who, I understand, have been faithful to you and have refused as well as you to dishonor the commission you have from England. I assure you on my word and honour, I will perform nicely what I have promised.”

It was a trap. Captain William Kidd fell for it, and he was arrested on July 6, 1699, as soon as he set foot on Massachusetts land. He was transported to London where he went to trial and lost. Captain Kidd was convicted in a sham of a trial where he was not allowed to testify on his own behalf nor cross-examine witnesses. On May 23, 1701, Kidd was hung by his neck and strung out to rot in a body cage for privateer and pirate viewing.

——

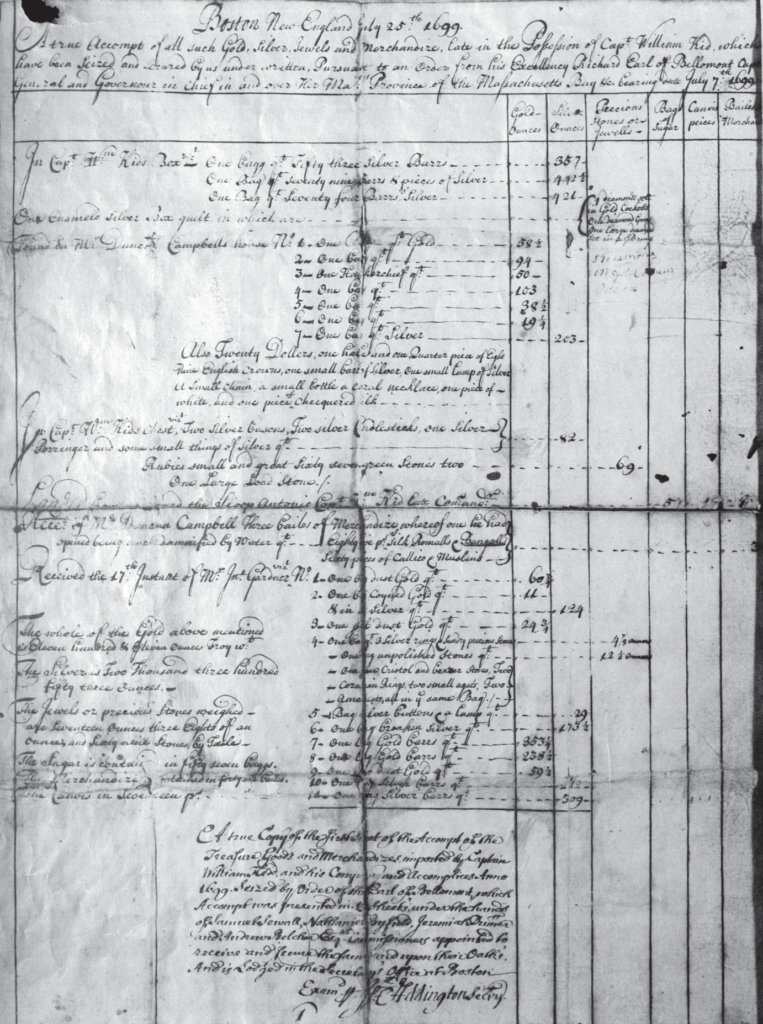

So what became of Captain Kidd’s buried treasure? Some of this is well documented. Other portions—possibly the majority of his take—is not. Part of Kidd’s defense strategy was to offset his predicament by buying his way out. Somehow, through someone, the Gardiner family produced treasure from Captain Kidd and turned it over to Governor Bellomont.

This is perfectly documented, and the recorded inventory shows a tally of 1,111 ounces of gold, 2,549 ounces of silver, and a small bag of emeralds weighing 66 ounces. The value at that time, in July of 1699, put Kidd’s treasure at 5,453.6 British pounds. In today’s USD, his gold, silver, and emeralds would be worth about 2.1 million dollars.

Most people at the time, and most historians today, feel Captain Kidd’s total treasure taken from the Quedagh Merchant was far more than that. Far, far more. It’s somewhat safe to say that Kidd left the bulky treasure—silk and satin bales, barrels of tea, crates of coffee, and sacks of sugar—on the hidden ship in the Caribbean. Once Kidd was doomed, the remaining crew disbursed what was left and burned the ship. Salvagers discovered the wreckage in 2007 exactly where Kidd was suspected to have anchored it.

But what became of other valuables known to be on board the Quedagh Merchant when Kidd took it under full authority of the British Monarch? Riches like precious gems of sapphire, rubies, diamonds, topaz, and opals? What about jewelry such as pearl strings, tiaras, and clusters in brooches? Chalices? Porringers? Candlesticks? Crucifixes? And religious figurines? What became of the other stuff that was really worth something?

You probably don’t need to look further than those privy to Kidd’s treasure on Gardiners Island—the Lion Gardiner family.

This circles back to the central question—what really became of Captain Kidd’s buried treasure. It’s obvious what the Gardiners turned over to the British Crown was mainly gold and silver. These commodities were not proportionately worth in 1699 what they are in 2020. Gold and silver were strictly regulated in price, and there would be no disputing their market value by weight. That made gold and silver predictable in price and easy to exchange.

The same couldn’t be said for precious stones or man-made artifacts embedding their beauty in artwork. Some of the Kidd treasure, assuming it was there, would be most challenging to price. Rightfully, some of the pieces would be priceless, and it’s these treasured works that are gone.

Let’s look at who the Gardiner family was and where they are today. Lion Gardiner was a British immigrant to Connecticut. In 1639, he bought the island from the chief of the Montaukett tribe for (reportedly) “a large black dog, some powder and shot, and a few Dutch blankets”. Lion Gardiner moved his wife, children, and a few workers to the island and began subsistence farming.

It was fertile land, and Lion Gardiner was an enterprising farmer. He was also a shrewd operator. Gardiner senior sought a royal patent with the clause that he and his family had the “right to possess the land forever”. This “in-perpetuity” clause remains in effect and today Gardiners Island is the oldest single landholding in the United States. Old Gardiner even got the King to sign-off on foreshore rights with the interesting measure of owning all sea shore out from land “as far as a large ox can wade before his belly gets wet”.

It was fertile land, and Lion Gardiner was an enterprising farmer. He was also a shrewd operator. Gardiner senior sought a royal patent with the clause that he and his family had the “right to possess the land forever”. This “in-perpetuity” clause remains in effect and today Gardiners Island is the oldest single landholding in the United States. Old Gardiner even got the King to sign-off on foreshore rights with the interesting measure of owning all sea shore out from land “as far as a large ox can wade before his belly gets wet”.

The Gardiner family is one of the wealthiest groups of generational folks in America. “Old money” that is, and not quite to current standards of Gates, Buffet, Bezos, and Zuckerberg. No, the Gardiners are more in line with the names Forbes, Rockefeller, Astor, and DuPont. It’s clear how Gardiner counterparts got their dry-land start, but there’s murkiness in Gardiners Island waters.

Shortly after Captain Kidd died, the Gardiner family showed signs of unusual income. They spent more than could logically be earned by marketing apples and corn and eggs and milk in New York markets. Successive Gardiners got progressively richer. They acquired large land tracts and secured lucrative lending arrangements.

Over the years, the heads of the Gardiner dynasty (who got a royal peerage “Lord of the Manor”) held lavish parties on Gardiners Island. The who’s who of society, old money and nouveau riche included, attended by invitation and hobnobbed in lavishly catered exclusivity. A Gardiner became an American First Lady and First Ladies like Jacqueline Kennedy were part of the Gardiners Island scene.

Robert David Lion Gardiner was the last Lord of the Manor at Gardiners Island. He was a colorful character, albeit eccentric, and all but confirmed where the family fortune arose. Robert Gardiner, the 16th Lord, showed many people artifacts from the “Kidd Collection” that remained in his family’s possession. He died in 2004 with no biological heirs.

Today, Gardiners Island (that once held colony status) is solely owned by a reclusive Gardiner relative, a removed niece named Alexandria Goelet. Estimators say the island property is worth several billion dollars, and no one publically knows the Gardiner family fortune’s mass. Maybe this wealth is what really became of Captain Kidd’s buried treasure.