This great guest post is by Andy Brunning, a UK Chemistry Teacher who hosts the fascinating website Compound Interest at www.compoundchem.com .

Decomposition is an incredibly complicated process, but we do know a little about the chemical culprits behind some of the terrible smells as the body breaks down.

Decomposition is an incredibly complicated process, but we do know a little about the chemical culprits behind some of the terrible smells as the body breaks down.

Before we look at specific compounds, it’s worth taking a look at the decomposition process as a whole.

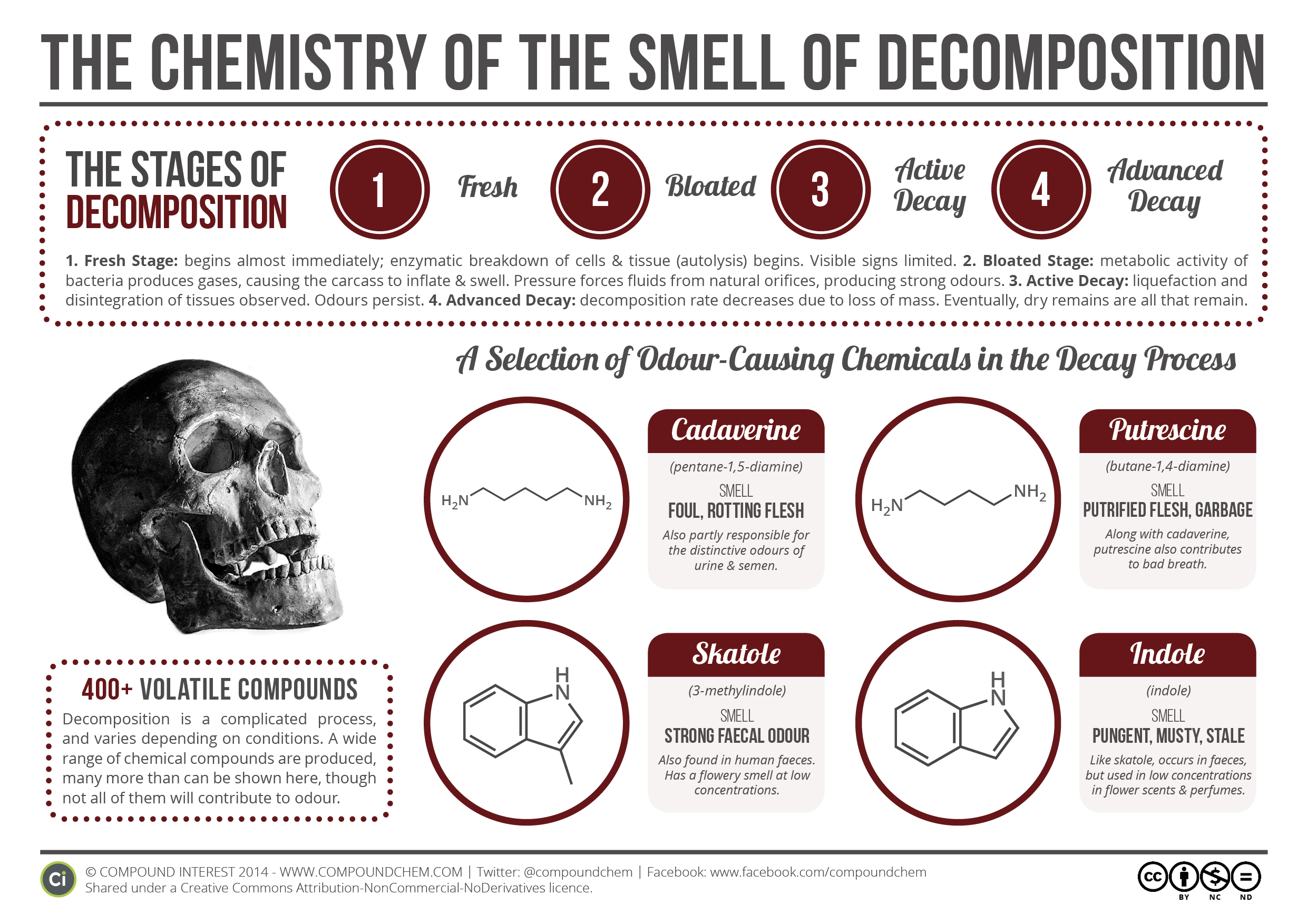

Decomposition, or ‘Decomp’ as it’s called in the death business, can be roughly divided into four stages: the fresh stage, the bloated stage, the active decay stage, and the advanced decay stage. Some overviews of the process also add in a final stage when all that is left of the corpse is dried remains. This can be skeletal, mummification, or fossilization.

The fresh stage of decay kicks off about four minutes after death.

Once the heart has stopped beating, the cells in the body are deprived of oxygen. As carbon dioxide and waste products build up, the cells start to break down as a result of enzymatic processes – these are known as autolysis. Initial visual signs of decomposition are minimal, although as autolysis progresses blisters and sloughing of skin may occur.

Once the heart has stopped beating, the cells in the body are deprived of oxygen. As carbon dioxide and waste products build up, the cells start to break down as a result of enzymatic processes – these are known as autolysis. Initial visual signs of decomposition are minimal, although as autolysis progresses blisters and sloughing of skin may occur.

The second stage of decay occurs as a result of the action of micro-organisms.

The actions of bacteria on the soft tissue of the body produces a variety of gases which cause the carcass to become bloated and swell in size. It’s claimed that the body can as much as double in size during this stage of decomposition. The sulfur-containing compounds that the bacteria release also cause discolouration of the skin, giving it a yellow-green hue.

As a result of the bloating, the increased pressure causes bodily fluids to be forced out of natural orifices, as well as potentially causing ruptures in the skin. This can cause a formidable odour; at this stage, if insects are able to access the body, flies will lay eggs in exposed orifices, which will in turn hatch into maggots which then devour the flesh.

As a result of the bloating, the increased pressure causes bodily fluids to be forced out of natural orifices, as well as potentially causing ruptures in the skin. This can cause a formidable odour; at this stage, if insects are able to access the body, flies will lay eggs in exposed orifices, which will in turn hatch into maggots which then devour the flesh.

The third stage is that of active decay.

At this stage, the ongoing action of bacteria activity and decomposition leads to the liquefaction of tissues, and the persistence of the strong odour. It is during this stage that the cadaver loses the greatest mass.

The final stage, advanced decay, occurs once most of the cadaveric material has already decomposed.

A wide range of factors can affect the decomposition process, including whether the body is buried, and the ambient temperature.

These factors also have an effect on the large number of compounds produced during the decomp process. Considering that, as a species, we’ve been dying and decomposing for thousands of years, we know surprisingly little about the specifics of the process and the chemicals involved.

These factors also have an effect on the large number of compounds produced during the decomp process. Considering that, as a species, we’ve been dying and decomposing for thousands of years, we know surprisingly little about the specifics of the process and the chemicals involved.

What we do know is that there are several key compounds that contribute towards the characteristic odours of decay.

Two of these are pretty much named for this contribution: cadaverine and putrescine. The aroma of both is loosely described as ‘rotting flesh’, and they have relatively low odour thresholds – meaning that not a lot is required in order for them to make their presence felt by your nostrils. Oddly enough, their presence in your body isn’t limited until after you die, however. Both crop up in cases of oral halitosis (i.e. bad breath), as well as in urine and semen, contributing to their odours.

Two other key compounds are skatole and indole.

Skatole, as you may have already guessed from the name, has a strong odour of faeces, whilst indole has a mustier, mothball-like smell. Both compounds are found in human and animal faeces, so it’s little surprise that they can contribute unpleasantness to the odour of a decomposing corpse. The strange thing about both is that, at low concentrations, they actually have quite pleasant, flowery aromas, leading to an array of unexpected uses. Indole is found in jasmine oil, which is used in many perfumes, whilst synthetic skatole is used in small amounts as a flavouring in ice creams, as well as also being found in perfumes.

Skatole, as you may have already guessed from the name, has a strong odour of faeces, whilst indole has a mustier, mothball-like smell. Both compounds are found in human and animal faeces, so it’s little surprise that they can contribute unpleasantness to the odour of a decomposing corpse. The strange thing about both is that, at low concentrations, they actually have quite pleasant, flowery aromas, leading to an array of unexpected uses. Indole is found in jasmine oil, which is used in many perfumes, whilst synthetic skatole is used in small amounts as a flavouring in ice creams, as well as also being found in perfumes.

A range of sulfur-containing compounds also contribute to the smell of decomposition.

Produced by the action of bacteria, compounds such as hydrogen sulfide (which smells of rotten eggs), methanethiol (rotting cabbage), dimethyl disulfide (garlic-like) and dimethyl trisulfide (foul/garlic) all add to the unpleasant scent. A whole range of other compounds are also produced as the tissues of the body decompose – some studies have identified over 400 different compounds, although not all of these will be contributors to the odour.

Produced by the action of bacteria, compounds such as hydrogen sulfide (which smells of rotten eggs), methanethiol (rotting cabbage), dimethyl disulfide (garlic-like) and dimethyl trisulfide (foul/garlic) all add to the unpleasant scent. A whole range of other compounds are also produced as the tissues of the body decompose – some studies have identified over 400 different compounds, although not all of these will be contributors to the odour.

There’s still a lot we don’t know about decomposition.

Using human corpses in research on decomp is limited in many countries for ethical reasons, so in many studies pigs are used as models. In the USA, however, there are a number of ‘body farms’ – facilities set up in a several states to study decomposition of human remains. The bodies they study are those who have chosen to donate their remains; these are then allowed to decay in a range of conditions and studied as they do so. This can help researchers determine the appearance and chemical emissions of bodies at various stages of decay, which can then inform police investigations where bodies are discovered, helping to determine a more accurate time of death.

Using human corpses in research on decomp is limited in many countries for ethical reasons, so in many studies pigs are used as models. In the USA, however, there are a number of ‘body farms’ – facilities set up in a several states to study decomposition of human remains. The bodies they study are those who have chosen to donate their remains; these are then allowed to decay in a range of conditions and studied as they do so. This can help researchers determine the appearance and chemical emissions of bodies at various stages of decay, which can then inform police investigations where bodies are discovered, helping to determine a more accurate time of death.