Great stories—well told—really change the world. No one understands this better than Jerry B. Jenkins. Over 40 years, he’s authored story art. Jerry Jenkins’ messages have life-shifted millions because he speaks the truth—in fact and in fiction. An insatiable learner, Jerry’s passion for prose astonishingly rendered 186 books (and counting) including the best-selling Left Behind series. 21 of Jerry Jenkins’ books hit the New York Times bestseller list. 7 debuted at number one. Here, Jerry B. Jenkins tells you how to write a book in 20 steps.

Great stories—well told—really change the world. No one understands this better than Jerry B. Jenkins. Over 40 years, he’s authored story art. Jerry Jenkins’ messages have life-shifted millions because he speaks the truth—in fact and in fiction. An insatiable learner, Jerry’s passion for prose astonishingly rendered 186 books (and counting) including the best-selling Left Behind series. 21 of Jerry Jenkins’ books hit the New York Times bestseller list. 7 debuted at number one. Here, Jerry B. Jenkins tells you how to write a book in 20 steps.

Jerry Jenkins is a prolific writer—right across the spectrum. He’s written stand-alones, biographies, adult and children’s fiction as well as Christian education, devotion and documentary works. Jerry’s even penned mysteries and thrillers. Jerry Jenkins now devotes time to helping others improve their craft and realize full potential. He’s a mentor to many—a role model to all.

I was flattered—actually astonished—getting a recent unsolicited email from Jerry Jenkins’ marketing team. They recognized DyingWords as a credible blog and writing resource. We had a great exchange. This led to a mentoring inclusion in Jerry’s Writers Guild. It’s a phenomenal club with sound writing guidance and top resource people including personal online time with Jerry Jenkins. And Jerry graciously shared his newly-published writing guide as a DyingWords guest post.

Here’s Jerry B. Jenkins’ fascinating guide originally published on JerryJenkins.com. It’s called How to Write a Book: Everything You Need to Know in 20 Steps.

* * *

So you want to write a book.

Becoming an author can change your life—not to mention give you the ability to impact thousands, even millions, of people. However, writing a book is no cakewalk. As a 21-time New York Times Bestselling author, I can tell you: It’s far easier to quit than to finish. When you run out of ideas, when your own message bores you, or when you become overwhelmed by the sheer scope of the task, you’re going to be tempted give up.

Becoming an author can change your life—not to mention give you the ability to impact thousands, even millions, of people. However, writing a book is no cakewalk. As a 21-time New York Times Bestselling author, I can tell you: It’s far easier to quit than to finish. When you run out of ideas, when your own message bores you, or when you become overwhelmed by the sheer scope of the task, you’re going to be tempted give up.

But what if you knew exactly:

- Where to start…

- What each step entails…

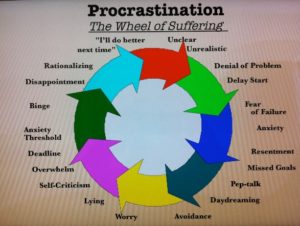

- How to overcome fear, procrastination, and writer’s block…

- And how to keep from feeling overwhelmed?

You can do this—and more quickly than you might think, because these days you have access to more writing tools than ever. The key is to follow a proven, straightforward, step-by-step plan. My goal here is to offer you that plan.

I’ve used the techniques I outline below to write more than 180 books (including the Left Behind series) over the past 40 years. Yes, I realize averaging over four books per year is more than you may have thought humanly possible. But trust me—with a reliable blueprint, you can get unstuck and finish your book. This is my personal approach to how to write a book. I’m confident you’ll find something here that can change the game for you. So, let’s jump in.

Part One: Before You Begin

You’ll never regret—in fact, you’ll thank yourself later—for investing the time necessary to prepare for such a monumental task. You wouldn’t set out to cut down a huge grove of trees with just an axe. You’d need a chain saw, perhaps more than one. Something to keep them sharp. Enough fuel to keep them running. You get the picture. Don’t shortcut this foundational part of the process.

1. Establish your writing space

To write your book, you don’t need a sanctuary. In fact, I started my career on my couch facing a typewriter perched on a plank of wood suspended by two kitchen chairs.

To write your book, you don’t need a sanctuary. In fact, I started my career on my couch facing a typewriter perched on a plank of wood suspended by two kitchen chairs.

What were you saying about your setup again? We do what we have to do. And those early days on that sagging couch were among the most productive of my career. Naturally, the nicer and more comfortable and private you can make your writing lair (I call mine my cave), the better. (If you dedicate a room solely to your writing, you can even write off a portion of your home mortgage, taxes, and insurance proportionate to that space.)

Real writers can write anywhere. Some write in restaurants and coffee shops. My first fulltime job was at a newspaper where 40 of us clacked away on manual typewriters in one big room—no cubicles, no partitions, conversations hollered over the din, most of my colleagues smoking, teletype machines clattering. Cut your writing teeth in an environment like that, and anywhere else seems glorious.

2. Assemble your writing tools.

In the newspaper business, there was no time to handwrite our stuff and then type it for the layout guys. So I have always written at a keyboard. Most authors do, though some handwrite their first drafts and then keyboard them onto a computer or pay someone to do that.

No publisher I know would even consider a typewritten manuscript, let alone one submitted in handwriting. The publishing industry runs on Microsoft Word, so you’ll need to submit Word document files. Whether you prefer a Mac or a PC, both will produce the kinds of files you need.

And if you’re looking for a muscle-bound electronic organizing system, you can’t do better than Scrivener. It works well on both PCs and Macs, and it nicely interacts with Word files.

And if you’re looking for a muscle-bound electronic organizing system, you can’t do better than Scrivener. It works well on both PCs and Macs, and it nicely interacts with Word files.

Just remember, Scrivener has a steep learning curve, so familiarize yourself with it before you start writing. Scrivener users know that taking the time to learn the basics is well worth it.

So, what else do you need? If you are one who handwrites your first drafts, don’t scrimp on paper, pencils, or erasers. Don’t shortchange yourself on a computer either. Even if someone else is keyboarding for you, you’ll need a computer for research and for communicating with potential agents, editors, publishers. Get the best computer you can afford, the latest, the one with the most capacity and speed.

Try to imagine everything you’re going to need in addition to your desk or table, so you can equip yourself in advance and don’t have to keep interrupting your work to find things like:

- Staplers

- Paper clips

- Rulers

- Pencil holders

- Pencil sharpeners

- Note pads

- Printing paper

- Paperweight

- Tape dispensers

- Cork or bulletin boards

- Clocks

- Bookends

- Reference works

- Space heaters

- Fans

- Lamps

- Beverage mugs

- Napkins

- Tissues

- You name it

Last, but most crucial, get the best, most ergonomic chair you can afford. If I were to start my career again with that typewriter on a plank, I would not sit on that couch. I’d grab another straight-backed kitchen chair or something similar and be proactive about my posture and maintaining a healthy spine. There’s nothing worse than trying to be creative and immerse yourself in writing while you’re in agony. The chair I work in today cost more than my first car!

Last, but most crucial, get the best, most ergonomic chair you can afford. If I were to start my career again with that typewriter on a plank, I would not sit on that couch. I’d grab another straight-backed kitchen chair or something similar and be proactive about my posture and maintaining a healthy spine. There’s nothing worse than trying to be creative and immerse yourself in writing while you’re in agony. The chair I work in today cost more than my first car!

If you’ve never used some of the items I listed above and can’t imagine needing them, fine. But make a list of everything you know you’ll need so when the actual writing begins, you’re already equipped. As you grow as a writer and actually start making money at it, you can keep upgrading your writing space. Where I work now is light years from where I started. But the point is, I didn’t wait to start writing until I could have a great spot in which to do it.

3. Break the project into small pieces.

Writing a book feels like a colossal project because it is! But your manuscript will be made up of many small parts. An old adage says that the way to eat an elephant is one bite at a time. Try to get your mind off your book as a 400-or-so-page monstrosity. It can’t be written all at once any more than that proverbial elephant could be eaten in a single sitting.

See your book for what it is: a manuscript made up of sentences, paragraphs, pages. Those pages will begin to add up, and though after a week you may have barely accumulated double digits, a few months down the road you’ll be into your second hundred pages. So keep it simple.

Start by distilling your big book idea from a page or so to a single sentence—your premise. The more specific that one-sentence premise, the more it will keep you focused while you’re writing. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Before you can turn your big idea into one sentence, which can then be expanded to an outline, you have to settle on exactly what that big idea is.

4. Settle on your BIG idea.

To be book-worthy, your idea has to be killer. You need to write something about which you’re passionate, something that gets you up in the morning, draws you to the keyboard, and keeps you there. It should excite not only you but also anyone you tell about it. I can’t overstate the importance of this.

If you’ve tried and failed to finish your book before—maybe more than once—it could be that the basic premise was flawed. Maybe it was worth a blog post or an article but couldn’t carry an entire book.

Think The Hunger Games, Harry Potter, or How to Win Friends and Influence People. The market is crowded, the competition fierce. There’s no more room for run-of-the-mill ideas. Your premise alone should make readers salivate.

Think The Hunger Games, Harry Potter, or How to Win Friends and Influence People. The market is crowded, the competition fierce. There’s no more room for run-of-the-mill ideas. Your premise alone should make readers salivate.

Go for the big concept book. How do you know you’ve got a winner? Does it have legs? In other words, does it stay in your mind, growing and developing every time you think of it? Run it past loved ones and others you trust. Does it raise eyebrows? Elicit Wows? Or does it result in awkward silences?

The right concept simply works, and you’ll know it when you land on it. Most importantly, your idea must capture you in such a way that you’re compelled to write it. Otherwise, you’ll lose interest halfway through and never finish.

5. Construct your outline.

Starting your writing without a clear vision of where you’re going will usually end in disaster. Even if you’re writing fiction and consider yourself a Pantser* as opposed to an Outliner, you need at least a basic structure. [*Those of us who write by the seat of our pants and, as Stephen King advises, put interesting characters in difficult situations and write to find out what happens]

You don’t have to call it an outline if that offends your sensibilities. But fashion some sort of a directional document that provides structure and also serves as a safety net. If you get out on that Pantser highwire and lose your balance, you’ll thank me for advising you to have this in place.

You don’t have to call it an outline if that offends your sensibilities. But fashion some sort of a directional document that provides structure and also serves as a safety net. If you get out on that Pantser highwire and lose your balance, you’ll thank me for advising you to have this in place.

Now if you’re writing a nonfiction book, there’s no substitute for an outline. Potential agents or publishers require this in your proposal. They want to know where you’re going, and they want to know that you know. What do you want your reader to learn from your book, and how will you ensure they learn it?

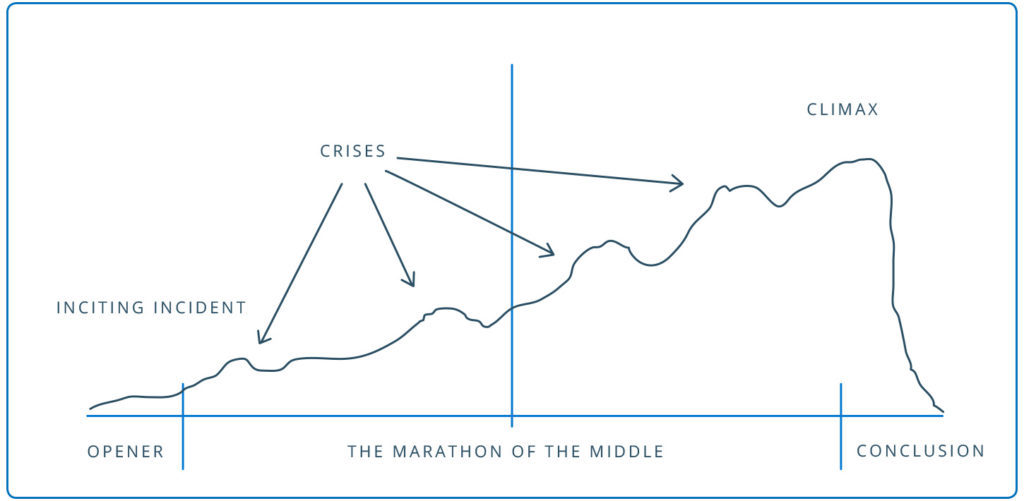

Fiction or nonfiction, if you commonly lose interest in your book somewhere in what I call the Marathon of the Middle, you likely didn’t start with enough exciting ideas.

That’s why an outline (or a basic framework) is essential. Don’t even start writing until you’re confident your structure will hold up through the end. You may recognize this novel structure illustration.

Did you know it holds up—with only slight adaptations—for nonfiction books too? It’s self-explanatory for novelists; they list their plot twists and developments and arrange them in an order that best serves to increase tension.

What separates great nonfiction from mediocre? The same structure! Arrange your points and evidence in the same way so you’re setting your reader up for a huge payoff, and then make sure you deliver.

If your nonfiction book is a memoir, an autobiography, or a biography, structure it like a novel and you can’t go wrong. But even if it’s a straightforward how-to book, stay as close to this structure as possible, and you’ll see your manuscript come alive.

Make promises early, triggering your reader to anticipate fresh ideas, secrets, inside information, something major that will make him thrilled with the finished product. While you may not have as much action or dialogue or character development as your novelist counterpart, your crises and tension can come from showing where people have failed before and how you’re going to ensure your reader will succeed. You can even make the how-to project look impossible until you pay off that setup with your unique solution.

Keep your outline to a single page for now. But make sure every major point is represented, so you’ll always know where you’re going. And don’t worry if you’ve forgotten the basics of classic outlining or have never felt comfortable with the concept. Your outline must serve you. If that means Roman numerals and capital and lowercase letters and then Arabic numerals, you can certainly fashion it that way. But if you just want a list of sentences that synopsize your idea, that’s fine too.

Keep your outline to a single page for now. But make sure every major point is represented, so you’ll always know where you’re going. And don’t worry if you’ve forgotten the basics of classic outlining or have never felt comfortable with the concept. Your outline must serve you. If that means Roman numerals and capital and lowercase letters and then Arabic numerals, you can certainly fashion it that way. But if you just want a list of sentences that synopsize your idea, that’s fine too.

Simply start with your working title, then your premise, then—for fiction, list all the major scenes that fit into the rough structure above. For nonfiction, try to come up with chapter titles and a sentence or two of what each chapter will cover. Once you have your one-page outline, remember it is a fluid document meant to serve you and your book. Expand it, change it, play with it as you see fit—even during the writing process.

6. Set a firm writing schedule.

Ideally, you want to schedule at least six hours per week to write. That may consist of three sessions of two hours each, two sessions of three hours, or six one-hour sessions—whatever works for you. I recommend a regular pattern (same times, same days) that can most easily become a habit. But if that’s impossible, just make sure you carve out at least six hours so you can see real progress.

Having trouble finding the time to write a book? News flash—you won’t find the time. You have to make it.

Having trouble finding the time to write a book? News flash—you won’t find the time. You have to make it.

I used the phrase carve out above for a reason. That’s what it takes. Something in your calendar will likely have to be sacrificed in the interest of writing time. Make sure it’s not your family—they should always be your top priority. Never sacrifice your family on the altar of your writing career. But beyond that, the truth is that we all find time for what we really want to do.

Many writers insist they have no time to write, but they always seem to catch the latest Netflix original series or go to the next big Hollywood feature. They enjoy concerts, parties, ball games, whatever.

How important is it to you to finally write your book? What will you cut from your calendar each week to ensure you give it the time it deserves?

- A favorite TV show?

- An hour of sleep per night? (Be careful with this one; rest is crucial to a writer.)

- A movie?

- A concert?

- A party?

Successful writers make time to write. When writing becomes a habit, you’ll be on your way.

7. Establish a sacred deadline.

Without deadlines, I rarely get anything done. I need that motivation. Admittedly, my deadlines are now established in my contracts from publishers. If you’re writing your first book, you probably don’t have a contract yet. To ensure you finish your book, set your own deadline—then consider it sacred.

Tell your spouse or loved one or trusted friend. Ask that they hold you accountable. Now determine—and enter in your calendar—the number of pages you need to produce per writing session to meet your deadline. If it proves unrealistic, change the deadline now.

Tell your spouse or loved one or trusted friend. Ask that they hold you accountable. Now determine—and enter in your calendar—the number of pages you need to produce per writing session to meet your deadline. If it proves unrealistic, change the deadline now.

If you have no idea how many pages or words you typically produce per session, you may have to experiment before you finalize those figures. Say you want to finish a 400-page manuscript by this time next year. Divide 400 by 50 weeks (accounting for two off-weeks), and you get eight pages per week. Divide that by your typical number of writing sessions per week and you’ll know how many pages you should finish per session. Now is the time to adjust these numbers while setting your deadline and determining your pages per session.

Maybe you’d rather schedule four off weeks over the next year. Or you know your book will be unusually long. Change the numbers to make it realistic and doable, and then lock it in. Remember, your deadline is sacred.

8. Embrace procrastination (Really!)

You read that right. Don’t fight it; embrace it. You wouldn’t guess it from my 190+ published books, but I’m the king of procrastinators. Surprised? Don’t be. So many authors are procrastinators that I’ve come to wonder if it’s a prerequisite. The secret is to accept it and, in fact, schedule it.

I quit fretting and losing sleep over procrastinating when I realized it was inevitable and predictable, and also that it was productive. Sound like rationalization? Maybe it was at first. But I learned that while I’m putting off the writing, my subconscious is working on my book. It’s a part of the process. When you do start writing again, you’ll enjoy the surprises your subconscious reveals to you.

I quit fretting and losing sleep over procrastinating when I realized it was inevitable and predictable, and also that it was productive. Sound like rationalization? Maybe it was at first. But I learned that while I’m putting off the writing, my subconscious is working on my book. It’s a part of the process. When you do start writing again, you’ll enjoy the surprises your subconscious reveals to you.

So, knowing procrastination is coming, book it on your calendar. Take it into account when you’re determining your page quotas. If you have to go back in and increase the number of pages you need to produce per session, do that (I still do it all the time). But—and here’s the key—you must never let things get to where that number of pages per day exceeds your capacity.

It’s one thing to ratchet up your output from two pages per session to three. But if you let it get out of hand, you’ve violated the sacredness of your deadline. How can I procrastinate and still meet more than 190 deadlines? Because I keep the deadlines sacred.

9. Eliminate distractions to stay focused.

Are you as easily distracted as I am? Have you found yourself writing a sentence and then checking your email? Writing another and checking Facebook? Getting caught up in the come-ons for pictures of the 10 Sea Monsters You Wouldn’t Believe Actually Exist? Then you just have to check out that precious video from a talk show where the dad surprises the family by returning from the war. That leads to more and more of the same. Once I’m in, my writing is forgotten, and all of a sudden the day has gotten away from me.

The answer to these insidious time wasters? Look into these apps that allow you to block your email, social media, browsers, game apps, whatever you wish during the hours you want to write. Some carry a modest fee, others are free.

10. Conduct your research.

Yes, research is a vital part of the process, whether you’re writing fiction or nonfiction.

Fiction means more than just making up a story. Your details and logic and technical and historical details must be right for your novel to be believable. And for nonfiction, even if you’re writing about a subject in which you’re an expert—as I’m doing here—you’ll be surprised how ensuring you get all the facts right will polish your finished product.

In fact, you’d be surprised at how many times I’ve researched a fact or two while writing this blog post alone. The last thing you want is even a small mistake due to your lack of proper research.

Regardless the detail, trust me, you’ll hear from readers about it. Your credibility as an author and an expert hinges on creating trust with your reader. That dissolves in a hurry if you commit an error.

My favorite research resources are:

- World Almanacs: These alone list almost everything you need for accurate prose: facts, data, government information, and more. For my novels, I often use these to come up with ethnically accurate character names.

- The Merriam-Webster Thesaurus: The online version is great because it’s lightning fast. You couldn’t turn the pages of a hard copy as quickly as you can get where you want to onscreen. One caution: Never let it be obvious you’ve consulted a thesaurus. You’re not looking for the exotic word that jumps off the page. You’re looking for that common word that’s on the tip of your tongue.

- WorldAtlas.com: Here you’ll find nearly limitless information about any continent, country, region, city, town, or village. Names, monetary units, weather patterns, tourism info, and even facts you wouldn’t have thought to search for. I get ideas when I’m digging here, for both my novels and my nonfiction books.

11. Start calling yourself a writer.

Your inner voice may tell you, “You’re no writer and you never will be. What do you think you’re doing, trying to write a book?” That may be why you’ve stalled at writing your book in the past. But if you’re working at writing, studying writing, practicing writing, that makes you a writer. Don’t wait till you reach some artificial level of accomplishment before calling yourself a writer.

Your inner voice may tell you, “You’re no writer and you never will be. What do you think you’re doing, trying to write a book?” That may be why you’ve stalled at writing your book in the past. But if you’re working at writing, studying writing, practicing writing, that makes you a writer. Don’t wait till you reach some artificial level of accomplishment before calling yourself a writer.

A cop in uniform and on duty is a cop whether he’s actively enforced the law yet or not. A carpenter is a carpenter whether he’s ever built a house. Self-identify as a writer now and you’ll silence that inner critic—who, of course, is really you. Talk back to yourself if you must. It may sound silly, but acknowledging yourself as a writer can give you the confidence to keep going and finish your book.

Are you a writer? Say so.

Part Two: The Writing Itself

12. Think reader first.

This is so important that you should write it on a sticky note and affix it to your monitor so you’re reminded of it every time you write. Every decision you make about your manuscript must be run through this filter. Not you-first, not book-first, not editor-first, agent-first, or publisher-first. Certainly not your inner circle or critics-first. Reader-first, last, and always.

If every decision is based on the idea of reader-first, all those others benefit anyway. When fans tell me they were moved by one of my books, I think back to this adage and am grateful I maintained that posture during the writing.

If every decision is based on the idea of reader-first, all those others benefit anyway. When fans tell me they were moved by one of my books, I think back to this adage and am grateful I maintained that posture during the writing.

Does a scene bore you? If you’re thinking reader-first, it gets overhauled or deleted. Where to go, what to say, what to write next? Decide based on the reader as your priority. Whatever your gut tells you your reader would prefer, that’s your answer. Whatever will intrigue him, move him, keep him reading, those are your marching orders.

So, naturally, you need to know your reader. Rough age? General interests? Loves? Hates? Attention span? When in doubt, look in the mirror. The surest way to please your reader is to please yourself. Write what you would want to read and trust there is a broad readership out there that agrees.

13. Find your writing voice.

Discovering your voice is nowhere near as complicated as some make it out to be. You can find yours by answering these quick questions:

- What’s the coolest thing that ever happened to you?

- Who’s the most important person you told about it?

- What did you sound like when you did?

That’s your writing voice. It should read the way you sound at your most engaged. That’s all there is to it. If you write fiction and the narrator of your book isn’t you, go through the three-question exercise on the narrator’s behalf—and you’ll quickly master the voice.

Here’s a blog I posted that’ll walk you through the process.

14. Write a compelling opener.

If you’re stuck because of the pressure of crafting the perfect opening line, you’re not alone.

And neither is your angst misplaced. This is not something you should put off and come back to once you’ve started on the rest of the first chapter.

And neither is your angst misplaced. This is not something you should put off and come back to once you’ve started on the rest of the first chapter.

Oh, it can still change if the story dictates that. But settling on a good one will really get you off and running. It’s unlikely you’ll write a more important sentence than your first one, whether you’re writing fiction or nonfiction. Make sure you’re thrilled with it and then watch how your confidence—and momentum—soars.

Most great first lines fall into one of these categories:

Surprising

Fiction: “It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.” —George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four

Nonfiction: “By the time Eustace Conway was seven years old, he could throw a knife accurately enough to nail a chipmunk to a tree.” —Elizabeth Gilbert, The Last American Man

Dramatic Statement

Fiction: “They shoot the white girl first.” —Toni Morrison, Paradise

Nonfiction: “I was five years old the first time I ever set foot in prison.” —Jimmy Santiago Baca, A Place to Stand

Philosophical

Fiction: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” —Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina

Nonfiction: “It’s not about you.” —Rick Warren, The Purpose Driven Life

Poetic

Fiction: “When I finally caught up with Abraham Trahearne, he was drinking beer with an alcoholic bulldog named Fireball Roberts in a ramshackle joint just outside of Sonoma, California, drinking the heart right out of a fine spring afternoon. —James Crumley, The Last Good Kiss

Nonfiction: “The village of Holcomb stands on the high wheat plains of western Kansas, a lonesome area that other Kansans call ‘out there.’” —Truman Capote, In Cold Blood

Great opening lines from other classics may give you ideas for yours.

Here’s a list of famous openers.

15. Fill your story with conflict and tension.

Your reader craves conflict, and yes, this applies to nonfiction readers as well. In a novel, if everything is going well and everyone is agreeing, your reader will soon lose interest and find something else to do—like watching paint dry.

Are two of your characters talking at the dinner table? Have one say something that makes the other storm out. Some deep-seeded rift in their relationship has surfaced. Is it just a misunderstanding that has snowballed into an injustice? Thrust people into conflict with each other. That’ll keep your reader’s attention.

Are two of your characters talking at the dinner table? Have one say something that makes the other storm out. Some deep-seeded rift in their relationship has surfaced. Is it just a misunderstanding that has snowballed into an injustice? Thrust people into conflict with each other. That’ll keep your reader’s attention.

Certain nonfiction genres won’t lend themselves to that kind of conflict, of course, but you can still inject tension by setting up your reader for a payoff in later chapters. Check out some of the current bestselling nonfiction works to see how writers accomplish this. Somehow they keep you turning those pages, even in a simple how-to title.

Tension is the secret sauce that will propel your reader through to the end. And sometimes that’s as simple as implying something to come.

16. Turn off your internal editor while writing the first draft.

Many of us are perfectionists and find it hard to get a first draft written—fiction or nonfiction—without feeling compelled to make every sentence exactly the way we want it. That voice in your head that questions every word, every phrase, every sentence, and makes you worry you’re being redundant or have allowed cliches to creep in—well, that’s just your editor alter ego.

He or she needs to be told to shut up. This is not easy. Deep as I am into a long career, I still have to remind myself of this every writing day. I cannot be both creator and editor at the same time. That slows me to a crawl, and my first draft of even one brief chapter could take days. Our job when writing that first draft is to get down the story or the message or the teaching—depending on your genre.

He or she needs to be told to shut up. This is not easy. Deep as I am into a long career, I still have to remind myself of this every writing day. I cannot be both creator and editor at the same time. That slows me to a crawl, and my first draft of even one brief chapter could take days. Our job when writing that first draft is to get down the story or the message or the teaching—depending on your genre.

It helps me to view that rough draft as a slab of meat I will carve tomorrow. I can’t both produce that hunk and trim it at the same time. A cliche, a redundancy, a hackneyed phrase comes tumbling out of my keyboard, and I start wondering whether I’ve forgotten to engage the reader’s senses or aimed for his emotions.

That’s when I have to chastise myself and say, “No! Don’t worry about that now! First thing tomorrow you get to tear this thing up and put it back together again to your heart’s content!” Imagine yourself wearing different hats for different tasks, if that helps—whatever works to keep you rolling on that rough draft. You don’t need to show it to your worst enemy or even your dearest love. This chore is about creating. Don’t let anything slow you down.

Some like to write their entire first draft before attacking the revision. As I say, whatever works. Doing it that way would make me worry I’ve missed something major early that will cause a complete rewrite when I discover it months later. I alternate creating and revising.

The first thing I do every morning is a heavy edit and rewrite of whatever I wrote the day before. If that’s ten pages, so be it. I put my perfectionist hat on and grab my paring knife and trim that slab of meat until I’m happy with every word. Then I switch hats, tell Perfectionist Me to take the rest of the day off, and I start producing rough pages again.

The first thing I do every morning is a heavy edit and rewrite of whatever I wrote the day before. If that’s ten pages, so be it. I put my perfectionist hat on and grab my paring knife and trim that slab of meat until I’m happy with every word. Then I switch hats, tell Perfectionist Me to take the rest of the day off, and I start producing rough pages again.

So, for me, when I’ve finished the entire first draft, it’s actually a second draft because I have already revised and polished it in chunks every day. THEN I go back through the entire manuscript one more time, scouring it for anything I missed or omitted, being sure to engage the reader’s senses and heart, and making sure the whole thing holds together.

I do not submit anything I’m not entirely thrilled with. I know there’s still an editing process it will will go through at the publisher, but my goal is to make my manuscript the absolute best I can before they see it.

Compartmentalize your writing vs. your revising and you’ll find that frees you to create much more quickly.

17. Preservere through The Marathon of the Middle.

Most who fail at writing a book tell me they give up somewhere in what I like to call The Marathon of the Middle. That’s a particularly rough stretch for novelists who have a great concept, a stunning opener, and they can’t wait to get to the dramatic ending. But they bail when they realize they don’t have enough cool stuff to fill the middle. They start padding, trying to add scenes just for the sake of bulk, but they’re soon bored and know readers will be too. This actually happens to nonfiction writers too.

The solution there is in the outlining stage, being sure your middle points and chapters are every bit as valuable and magnetic as the first and last. If you strategize the progression of your points or steps in a process—depending on nonfiction genre—you should be able to eliminate the strain in the middle chapters.

The solution there is in the outlining stage, being sure your middle points and chapters are every bit as valuable and magnetic as the first and last. If you strategize the progression of your points or steps in a process—depending on nonfiction genre—you should be able to eliminate the strain in the middle chapters.

For novelists, know that every book becomes a challenge a few chapters in. The shine wears off, keeping the pace and tension gets harder, and it’s easy to run out of steam. But that’s not the time to quit. Force yourself back to your structure, come up with a subplot if necessary, but do whatever you need to so your reader stays engaged.

Fiction writer or nonfiction author, The Marathon of the Middle is when you must remember why you started this journey in the first place. It isn’t just that you want to be an author. You have something to say. You want to reach the masses with your message.

Yes, it’s hard. It still is for me—every time. But don’t panic or do anything rash, like surrendering. Embrace the challenge of the middle as part of the process. If it were easy, anyone could do it.

18. Write a resounding ending.

This is just as important for your nonfiction book as your novel. It may not be as dramatic or emotional, but it could be—especially if you’re writing a memoir. But even a how-to or self-help book needs to close with a resounding thud, the way a Broadway theater curtain meets the floor.

How do you ensure your ending doesn’t fizzle?

- Don’t rush it. Give readers the payoff they’ve been promised. They’ve invested in you and your book the whole way. Take the time to make it satisfying.

- Never settle for close enough just because you’re eager to be finished. Wait till you’re thrilled with every word, and keep revising until you are.

- If it’s unpredictable, it had better be fair and logical so your reader doesn’t feel cheated. You want him to be delighted with the surprise, not tricked.

- If you have multiple ideas for how your book should end, go for the heart rather than the head, even in nonfiction. Readers most remember what moves them.

Part Three: All Writing Is Rewriting

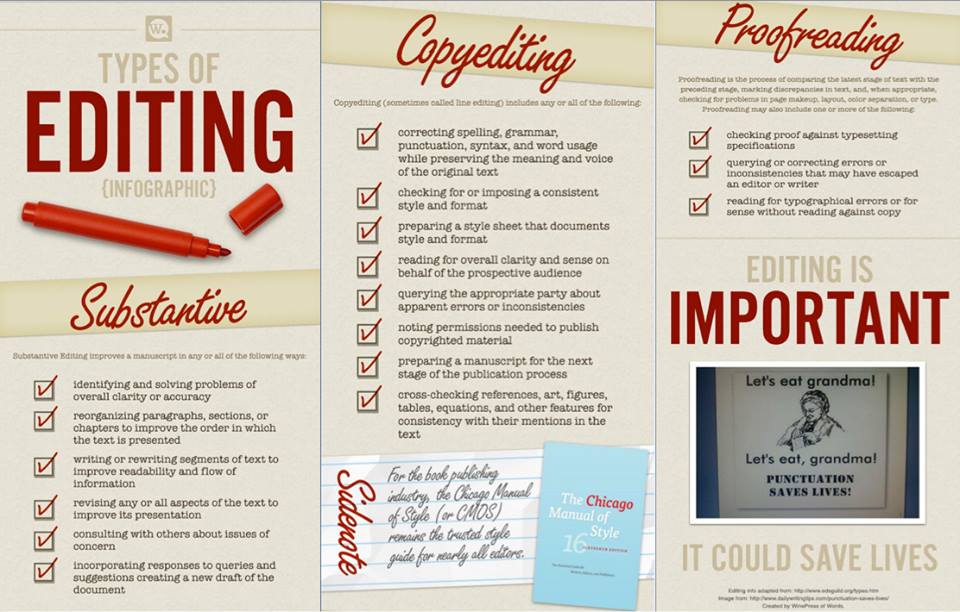

19. Become a ferocious self-editor.

Agents and editors can tell within the first two pages whether your manuscript is worthy of further consideration. That sounds unfair, and maybe it is. But it’s also reality, so we writers need to face it.

Agents and editors can tell within the first two pages whether your manuscript is worthy of further consideration. That sounds unfair, and maybe it is. But it’s also reality, so we writers need to face it.

How can they often decide that quickly on something you’ve devoted months, maybe years, to?

Because they can almost immediately envision how much editing would be required to make those first couple of pages publishable. If they decide the investment wouldn’t make economic sense for a 300-400-page manuscript, end of story.

Your best bet to keep an agent or editor reading your manuscript? You must become a ferocious self-editor. That means:

- Omit needless words

- Choose the simple word over one that requires a dictionary

- Avoid subtle redundancies, like “He thought in his mind…” (Where else would someone think?)

- Avoid hedging verbs like almost frowned, sort of jumped, etc.

- Generally remove the word that—use it only when absolutely necessary for clarity

- Give the reader credit and resist the urge to explain, as in, “She walked through the open door.” (Did we need to be told it was open?)

- Avoid too much stage direction (what every character is doing with every limb and digit)

- Avoid excessive adjectives

- Show, don’t tell

- And many more

For my full list and how to use them, click here. (It’s free.)

When do you know you’re finished revising? When you’ve gone from making your writing better to merely making it different. That’s not always easy to determine, but it’s what makes you an author.

And Finally—the Quickest Way to Succeed…

20. Find a mentor.

Get help from someone who’s been where you want to be. Imagine engaging a mentor who can help you sidestep all the amateur pitfalls and shave years of painful trial-and-error off your learning curve. Just make sure it’s someone who really knows the writing and publishing world. Many masquerade as mentors and coaches but have never really succeeded themselves.

Look for someone widely-published who knows how to work with agents, editors, and publishers.

There are many helpful mentors online. I teach writers through this free site, as well as in my members-only Writers Guild.