Al Capone. The name signifies ultimate dominance in the Prohibition-era American underworld. Capone, aka “Scarface” (a nickname he loathed), grew to rule Chicago’s gangsters as well as overlording many police officers and public officials. And he did so while in his twenties, before hubris took him down through tax evasion—not murder, extortion, robbery, drug trafficking, racketeering, prostitution, gambling, and his running over a thousand illegal speakeasies. Being crime’s kingpin was a mighty accomplishment for a man so young, and there are two primary reasons for how Al Capone criminally captured Chicago.

Al Capone. The name signifies ultimate dominance in the Prohibition-era American underworld. Capone, aka “Scarface” (a nickname he loathed), grew to rule Chicago’s gangsters as well as overlording many police officers and public officials. And he did so while in his twenties, before hubris took him down through tax evasion—not murder, extortion, robbery, drug trafficking, racketeering, prostitution, gambling, and his running over a thousand illegal speakeasies. Being crime’s kingpin was a mighty accomplishment for a man so young, and there are two primary reasons for how Al Capone criminally captured Chicago.

Al Capone was a true anti-social mastermind. He was a sadistic savage who used brute force to achieve his ends, and he masterfully manipulated others to do his murderous bidding. “Big Al” (he stood 5’10” and weighed 260 lbs.) was also a master strategist who intrinsically knew the flaws in human nature—greed and fear—and how to take an entire city under his control.

Capone ran Chicago’s underworld from the mid-1920s to his removal through financial conviction in 1931. During that time, when Chicago’s population was slightly over three million, the city experienced nearly one thousand gangland murders. Many, including the infamous St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, were ordered by Al Capone.

Before analyzing Al Capone’s colossal success and spectacular failure as well as identifying two primary reasons for how he captured Chicago, let’s look at who Al Capone was and how he became America’s most notorious gangster.

Alphonse Gabriel Capone was born in Brooklyn, New York on January 17, 1899. His parents were immigrants from the Italian Province of Salerno—his father was a barber and his mother a seamstress. Al Capone had eight siblings; two brothers going into law enforcement and two other brothers eventually taking roles in his criminal enterprise.

Capone was expelled from school at age 14 after assaulting a female teacher. He’d punched her in the face when she tried to discipline him for aggressive behavior. He then worked at odd jobs in New York City such as a candy store clerk, a bowling pin boy, an ammunition plant laborer, and a bookbinding cutter. But he found his calling at eighteen when he was hired as a barroom and brothel bouncer.

Al Capone was a large kid—a tough kid with a quick temper and a deeply ingrained mean streak. On the surface, though, Capone was charming, witty, and unusually clever. This character combination aligned him with one of New York’s leading criminals, Johnny Torrio.

It was in one of Torrio’s bars that Al Capone earned his nickname “Scarface”. A punk hoodlum called Frank Galluccio slashed Capone across the left side of his face leaving two huge gashes. Capone had insulted Galluccio’s sister which set off the fight. Capone was scarred for life, and he thereafter consciously avoided having himself photographed from the left.

Capone rose in the New York criminal culture. It was partly through Torrio’s influence and partly due to Capone’s natural ability to thrive in the underworld. It led to a move to Chicago.

Johnny Torrio was invited to partner with “Big Jim” Colosimo who headed the Chicago Outfit that operated in the Cicero suburb of west-central Chicago. Colosimo’s territory was constantly threatened by the North Side Gang run by the powerful Dean O’Banion who was supported by the infamous henchmen Bugsy Moran, Hymie Weiss, and Vincent Drucci. It was the eventual and ongoing rivalry between the Chicago Outfit and the North End Gang that caused most of the gangland hits.

Colosimo needed Capone’s muscle, and he needed Torrio’s brains. They created a symbiotic relationship, but there was one main problem. Colosimo was an old-school man. He approved of robbery, extortion, gambling, prostitution, and, of course, murder. But he was a pro-prohibitioner who disapproved of alcohol.

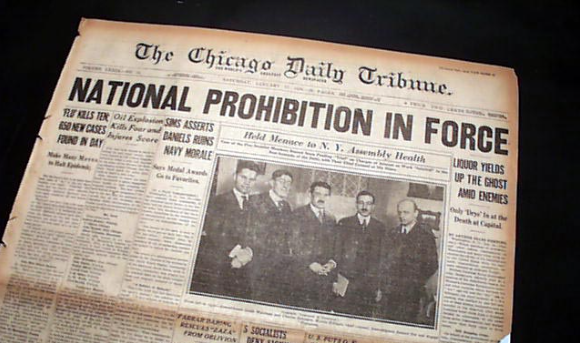

Torrio and Capone saw Prohibition as a gold mine. They saw Chicago as an untapped opportunity to make enormous profits by cornering the illegal booze manufacturing and delivery market. Colosimo, the boss, didn’t see it that way and had no plans to expand his enterprise into the bootlegging business.

On May 11, 1920, Big Jim Colosimo was shot dead as he went to a restaurant meeting with Johnny Torrio. History suspects Al Capone ordered the hit with Johnny Torrio’s blessing, but history shows Capone was conveniently in New York at the time. Regardless, Colosimo’s death allowed Torrio to take control of the Chicago Outfit with Capone as his right-hand man.

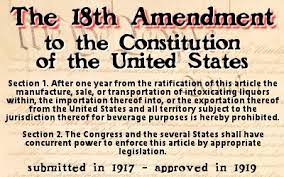

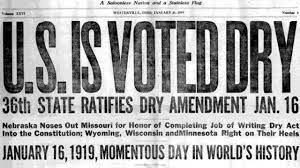

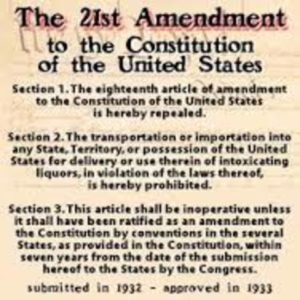

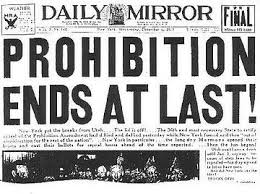

That arrangement lasted long enough for the Chicago Outfit to gain its upper hand in the illegal liquor business. Torrio and Capone made strong ties with Canadian alcohol manufacturers as Canada had no Prohibition rules whereas the US Act prohibited the manufacturing, distribution, and sale of all “recreational” liquor products. It was not illegal to possess or consume alcoholic beverages in the States—only to make and move them.

Tensions grew between the Chicago Outfit and Dean O’Banion’s North End Gang. On November 10, 1924, the Torrio/Capone alliance murdered O’Banion. In retaliation, the North Enders ambushed Johnny Torrio and wounded him so badly that Torrio resigned as head of the Outfit and returned to New York. This left Al Capone solely in charge and the gang violence quickly escalated.

Capone implemented every fear and intimidation tactic he could to eliminate his underworld rivals and force purchasing compliance on his marketplace. Capone’s loyal goons’ favorite weapon was the Thompson .45 submachine gun with 50-round magazines—the Chicago Typewriter, it was called. Capone sent multiple squads of gunmen after his targets, often shooting hundreds of bullets into buildings and passing cars.

One by one, Capone eliminated criminals like Hymie Weiss and Vincent Drucci. But a certain high-value hit, Bugsy Moran, played hard to get. This is when Capone set up the Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre in 1929. Capone’s men, three dressed in police uniforms, raided a Chicago garage where the North End Gang was holding a clandestine meeting. The men under Capone lined seven North Enders up against a brick wall and mowed them down with machine gun fire.

By sheer coincidence, good or bad luck depending on how you see it, Bugsy Moran was late for the meet and survived. However, with his gang decimated and his power weakened, Moran gave up and left the Chicago mob scene. This left Capone as the kingpin, except for a side rivalry.

In 1925, as Capone was ascending in Chicago’s crime hierarchy, he meddled in the Unione Siciliana which was a Sicilian-American benevolent society—a convenient place for money laundering. Capone deposed Joe Aiello as head of the society and replaced him with a Capone hack called Antinio Lombardo. This infuriated Aiello, and he made it his personal mission to take Al Capone out.

From this point forward, despite the North End threat, Capone lived under constant fear of being assassinated. He beefed up security by having fortified residences, hoards of bodyguards, a bulletproof limousine, and unpredictable travel habits. Capone began spending more time away from Chicago, buying a mansion in Florida and laying low in Las Vegas.

Rumors were that Al Capone had hideouts in Canada despite Capone’s famous quote, “I don’t even know what street Canada is on.” Moose Jaw in Saskatchewan claims fame for the “Capone Tunnels” under its city. So do places like London, Ontario, and Windsor across the river from Detroit.

While Aiello went after Capone, so did the Revenuers. Until the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, Al Capone was nearly untouchable in Chicago. Although Capone instilled mortal fear into his rivals, he had immense popularity with Chicagoans. Not only did the drinking public love Al Capone, so did the cops, the courts, and the civic authorities.

Capone played to the common greed as well as the common fear—two ingrained human condition frailties. He had hundreds, if not thousands, of people across the spectrum on his protection payroll. This included police at the patrol level as well as in high administration positions. He had the mayor in his pocket, the DA at his side, and enough goods on judges which forced them to hold his line.

The Roaring Twenties in Chicago was a time when law enforcement and the judiciary were pretty much of a joke. Officers were severely underpaid. Many had second jobs to make ends meet so they were wide open to bribes. So were politicians who appointed the court staff.

Capone knew he could intimidate enemies with the fear of brutal terror, and he knew he could buy his way to having greedy officials look the other way. He also knew he could purchase the hearts and minds of the common people with donations to churches, food pantries for the poor, housing for the displaced, funding for orphanages, and pensions for widows.

To most of the overlooking public, Al Capone was not a gangster. He was a successful businessman—a guy you’d like to have drinks around the pool with—who supplied liquor to a majority who hated Prohibition and viewed the law as wrong. Leave Al alone was the thinking. All he was doing was supplying entertainment to the city. Getting witnesses to testify against him was nearly impossible.

February 14, 1929, was a turning point in Capone’s criminal career. The tide of public support turned from this outrage in violence. Walter A. Strong, publisher of the Chicago Daily, turned to his good friend, newly inaugurated President Herbert Hoover for help to smash Capone and the Chicago Outfit. As Hoover recorded in his memoirs:

“Walter Strong made an argument that Chicago was in the hands of the gangsters, that the police and magistrates were completely under their control… that the Federal government was the only force by which the city’s ability to govern itself could be restored. At once I directed that all the Federal agencies concentrate on Mr. Capone and his allies.”

A second movement went against Al Capone. On March 24, 1930, Capone’s face appeared on the cover of Time Magazine. The caption and story weren’t flattering. On April 23, The Chicago Crime Commission issued its first Public Enemies List. There were 28 names on it and Al Capone was in first place, He became Public Enemy #1.

1929 wasn’t kind to Al Capone. Neither was 1931. Here’s a summary of Capone’s downfall:

March 27, 1929 — Capone was arrested outside a Chicago courthouse for contempt of court.

May 16, 1929 — Capone was arrested in Philadelphia on weapons charges.

May 17, 1929 — Capone plead guilty to the weapons charges with a plea deal. He received a one-year sentence that was served in an open prison setting.

An intense investigation into Capone’s finances was conducted in 1930.

March 13, 1931 — Capone was charged with income tax evasion for the year 1924.

June 5, 1931 — Capone was indicted on 22 counts of federal tax evasion for the years 1925 through 1929.

June 16, 1931 — Capone’s lawyers and the prosecution worked a plea deal to one single count of tax evasion. The judge refused to allow it. All counts went to trial.

October 17, 1931 — A jury convicted Capone on 5 counts of tax evasion. He was sentenced to 11 years in prison, fined $50,000, assessed court costs of $7,692, and made subject to $215,000 in interest due on back charges.

The prosecution proved a case that Capone’s traceable income was $1,038,654 from 1924 to 1929. The real amount was likely much higher. Some investigators estimated it to be $100 million which in 2023 inflated value is $1.7 billion.

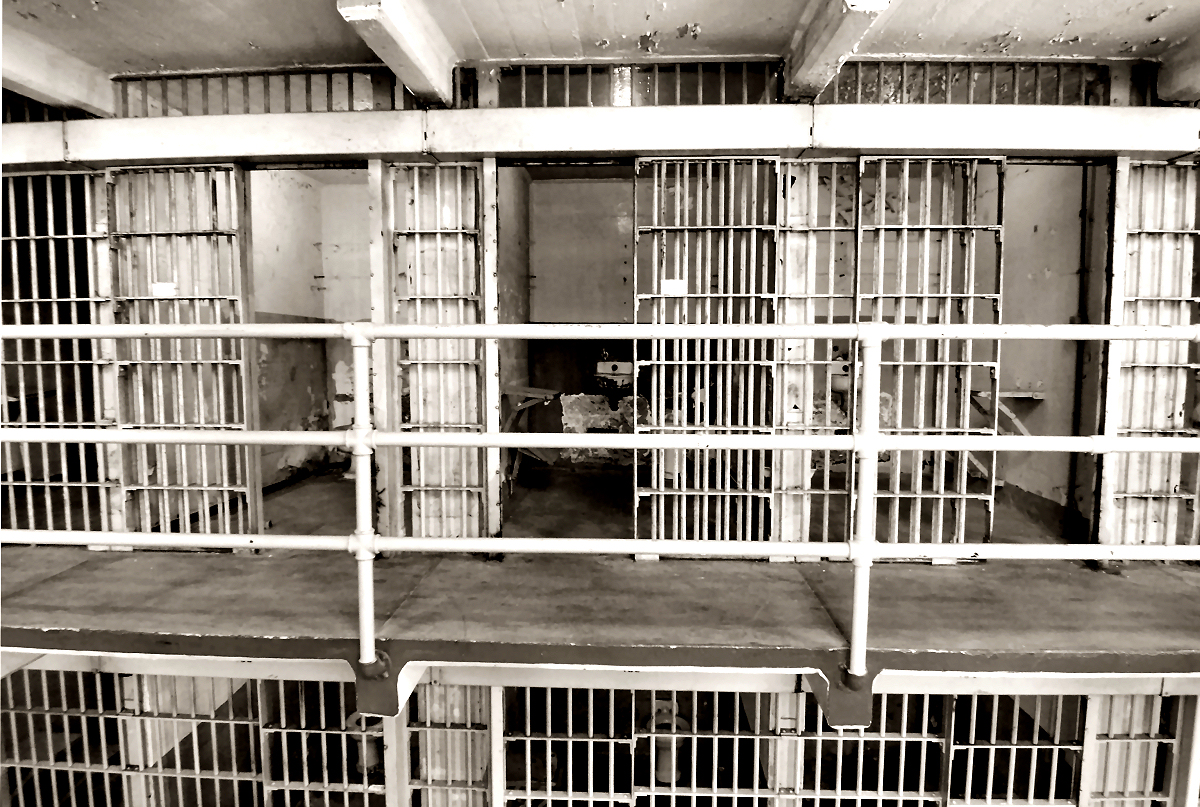

Al Capone went straight from trial to jail. First, he was incarcerated in the U.S. Penitentiary, Atlanta. In 1934, Capone was transferred to Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay. He stayed there until 1939 when he was paroled due to medical conditions.

Capone suffered from an untreated syphilis infection which ate away his brain. He was nearly non-functional when he returned to his Florida residence. He lingered on in an invalid state until he died of heart failure on January 25, 1947. Al Capone was buried just outside Chicago and in the Capone family plot.

This post opened by stating there were two primary reasons for how Al Capone criminally captured Chicago. They’ve been mentioned throughout the text, but there are many supporting characteristics to Al Capone’s character that allowed him to achieve his power. Here’s a few of them:

Charisma and Leadership — Capone possessed a commanding personality—highly energized, witty, yet serious. He inspired loyalty among his associates and maintained discipline throughout his organization.

Outstanding Presence — Al Capone was meticulous in appearance. Clean-shaven, short hair, impeccable suits, shirts, and ties, with perfectly polished shoes. He knew how important turnout was for respect, and he demanded the same professional look in his men.

Strategic Mindset — He was a shrewd businessman who saw opportunities, weighed risks, and focussed on reward. One of these was the immense opportunity offered him through the Act of Prohibition.

Adaptability — Capone was quick to change tactics when necessary. He understood the concepts of overall strategy supported by flexible tactics.

Exploiting the Civic Environment — Capone instinctively realized how malleable humans are. He knew most folks, public, private, and civil officials, naturally take an easy route out when offered a choice.

Corruption and Political Ties — He and his gang infiltrated the highest levels of Chicago’s political circles. He exploited them through bribery, blackmail, threats, and rewards that were impossible to refuse.

Community Support — At the street level, those who weren’t terrified of Al Capone worshipped him. He was instrumental in supplying the common person with the basic securities and necessities of life.

Absolute Ruthlessness — Those who opposed or crossed Capone ended up dead. And not dead by nice means. Capone had his enemies tortured, maimed, and exterminated in horrible ways… and the word got around.

If Capone had put his intelligence, organizational skills, and drive toward legitimate purposes, there’s no telling what he might have achieved. But he didn’t. It was the nature of this beast to be a bullying antisocial reprobate. He thrived knowing humans primarily respond out of greed and out of fear. He played to those flaws, and that is how Al Capone criminally captured Chicago.