The word “mummy” conjures images of ragged-wrapped, stretch-armed, walking dreads of the dead—frenzied figures from Hollywood’s hideous horror. Like Dracula, Frankenstein, and the hairy old Wolfman, mummies were classic fictional frights. But, in reality, mummies are tangible ghosts. They’re bodies that stick around—long after death—and they’re still here, fascinating us with mystical gore.

The word “mummy” conjures images of ragged-wrapped, stretch-armed, walking dreads of the dead—frenzied figures from Hollywood’s hideous horror. Like Dracula, Frankenstein, and the hairy old Wolfman, mummies were classic fictional frights. But, in reality, mummies are tangible ghosts. They’re bodies that stick around—long after death—and they’re still here, fascinating us with mystical gore.

Mummification is the process of stopping your body’s natural decomposition after death. Nature built a recycling system into all of us including your cat, your dog, crocodile, cobra, monkey, macaw, and your pet parrot—all have been made into mummies.

Where did this preservation process originate? How does it work? Is mummification still done today?

Where did this preservation process originate? How does it work? Is mummification still done today?

Or is the art of making everlasting mummies lost forever?

The English word “mummy” originated from the Latin term “mumia“ and the Arabic term “mumiya“ which meant a preserved corpse. The Old English Dictionary defined mummy as “A human or animal body embalmed (according to the ancient Egyptian or some analogous method) as a preparation for burial”.

Chamber’s Cyclopedia goes a step further. “A human or animal body desiccated by exposure to sun or air. Also applied to the frozen carcass of a human or animal embedded in prehistoric ice or snow”.

Scientifically, a mummy is simply a being who’s soft tissue has been long preserved after death. Normally when a person dies, the process of decomposition sets in immediately and is divided into two actions.

The first is autolysis which is the body’s enzymes beginning to digest themselves. This is followed by putrefaction which is the bacterial breakdown of organic matter.

The first is autolysis which is the body’s enzymes beginning to digest themselves. This is followed by putrefaction which is the bacterial breakdown of organic matter.

The rate and manner of decomposition is dependent on many factors. Mainly it’s the surrounding environment’s elements of heat or cold, humidity, exposure to air, and the physical makeup of the body itself. Large, fat corpses in a hot humid location will rot much faster than a small, skinny one in a cool dry setting.

Mummies are classified into two groups.

One is termed anthropogenic which means it’s intentionally preserved or manmade. The other is termed spontaneous. These mummies naturally occur due to death taking place in a suitable environment like a hot dry desert, a cold icy glacier, or the oxygen depleted, anaerobic depths of a peat bog.

One is termed anthropogenic which means it’s intentionally preserved or manmade. The other is termed spontaneous. These mummies naturally occur due to death taking place in a suitable environment like a hot dry desert, a cold icy glacier, or the oxygen depleted, anaerobic depths of a peat bog.

The anthropogenic mummification process has been around 10,000 years and evolved through centuries of experimentation. Plus a lot of trial and error.

The earliest human mummies are found in South America and are more like hybrid corpse-statues than the fully preserved, full sized cadavers of the Egyptians. The Chinchorros of Chile disarticulated the bodies, sun-dried the sections, then sewed them together with sinew, sticks, and straw. It seems they were kept in their houses for the sake of the family rather than the deceased.

The earliest human mummies are found in South America and are more like hybrid corpse-statues than the fully preserved, full sized cadavers of the Egyptians. The Chinchorros of Chile disarticulated the bodies, sun-dried the sections, then sewed them together with sinew, sticks, and straw. It seems they were kept in their houses for the sake of the family rather than the deceased.

Man-made mummies have been found on every continent of human habitation. They’re common to China, Asia, Europe, Australia, Africa, and North America, but mostly attributed to suitable sub-climates, including the islands of Papua New Guinea where they practiced shrinking heads.

The most famous mummies were made by ancient Egyptians.

Anthropogenic preservation has been recorded in Egypt since 3500 BC as their culture’s belief in the afterlife evolved. The early residents of the Upper Nile buried their dead in the hot, dry sand and made the remarkable observation that this preserved bodies in a permanent state.

This led to their profound conclusion that since the body remained intact, therefore the soul must remain intact after death as well.

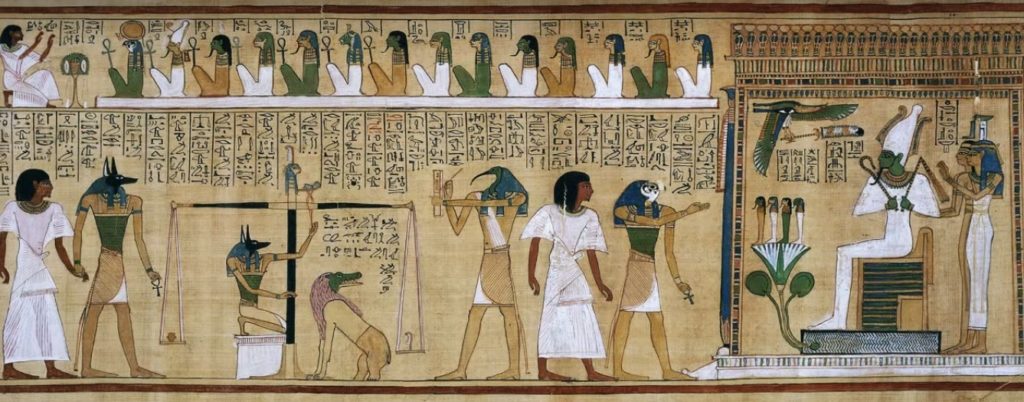

Ancient Egyptians saw a connection between the preservation of body and wellness of the soul in the afterlife. They believed if a body was well-prepared for eternity then so would the soul. Progressively, this led to advanced preservation techniques. Fortunately, it was clearly recorded.

Ancient Egyptians saw a connection between the preservation of body and wellness of the soul in the afterlife. They believed if a body was well-prepared for eternity then so would the soul. Progressively, this led to advanced preservation techniques. Fortunately, it was clearly recorded.

Two sources exist that describe the mummification process Egyptians perfected. One surviving papyri translated as The Ritual Of The Embalming. It describes more of the ceremonial practices than the practical. Herodotus’ Histories, however, left us with an intricate manual of exactly how human mummification was done at the height of the craft—the New Kingdom’s 18th through 20th dynasties in the period of 1570 to 1075 BC when the world’s outstanding mummies were made.

The instructions go like this:

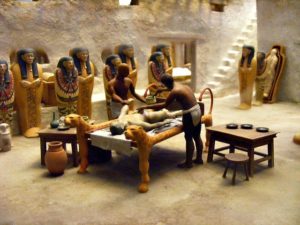

Step One: Organ Removal

First, make a small incision approximately 4 inches long on the left side of the abdomen. Then remove most of the organs through this small opening, cutting them away one by one. The exception is the heart. Leave the heart intact because it’s the seat of intelligence and needs a last judgement before the soul enters the next life.

First, make a small incision approximately 4 inches long on the left side of the abdomen. Then remove most of the organs through this small opening, cutting them away one by one. The exception is the heart. Leave the heart intact because it’s the seat of intelligence and needs a last judgement before the soul enters the next life.

The intestines, stomach, liver, and lungs are also regarded as an essential requirement for the body in the afterlife. So, after their removal, preserve each separately inside a canopic jar. Each jar is protected by its own god whose head is represented on the jar lid.

Brains used to be removed through the nose using a metal implement, however our best Egyptian mummies now have their brains left in place. As in life, the brain does not seem to have any use after death, so ignore it and leave the brain to dry in place.

Step Two: Sterilizing and Packing the Body

Wash out the empty body cavity with palm wine. It is alcohol and acts as a sterilizing agent. Next, mix the palm wine with pine resin. This is an antibacterial agent.

Wash out the empty body cavity with palm wine. It is alcohol and acts as a sterilizing agent. Next, mix the palm wine with pine resin. This is an antibacterial agent.

Again, following ancient methods, pack small linen bags containing crushed spices, myrrh and sawdust inside the body to maintain its form. Stitch the abdomen up and seal it with hot beeswax.

Step Three: The Protective Coating

Blend together specific quantities of plant oil, pine resin, spices, and beeswax. Brush this mixture over the entire surface of the body to create an even layer. Leave this outer coating to set.

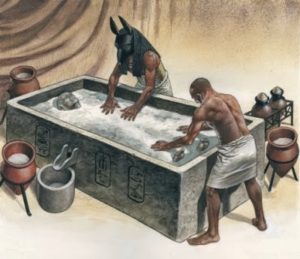

Step Four: The Natron Solution

Now treat the body with the Egyptian salt called ‘natron’. It’s made of four constituent parts; sodium carbonate, sodium bicarbonate, sodium chloride, and sodium sulphate. If Egyptian natron is not readily available, carefully measure each of these components to recreate the naturally occurring natron. Pour the blended salts into deionised water to create a solution of optimum concentration.

Now treat the body with the Egyptian salt called ‘natron’. It’s made of four constituent parts; sodium carbonate, sodium bicarbonate, sodium chloride, and sodium sulphate. If Egyptian natron is not readily available, carefully measure each of these components to recreate the naturally occurring natron. Pour the blended salts into deionised water to create a solution of optimum concentration.

Also, place the intestines, stomach, liver, and lung in the same natron solution, within their individual containers.

Leave the body and organs in this solution for exactly 70 days to allow the necessary chemical changes to occur. As water is drawn out of the body through the process of osmosis, the natron salts diffuse into the body’s soft tissue and the carbonates combine with the fats, turning them into a stable form more resistant to the process of decay.

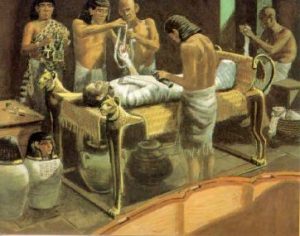

Step Five: Wrapping and Drying

Remove the body from the natron solution and dry it out for two weeks in a sealed unit, set to a specific combination of low humidity and warm temperature of the Egyptian summer environment.

Remove the body from the natron solution and dry it out for two weeks in a sealed unit, set to a specific combination of low humidity and warm temperature of the Egyptian summer environment.

Begin the long process of wrapping, using strips of linen cut to varying dimensions to fit different parts of the body. Seal each layer with melted pine resin and beeswax.

Remove the intestines, stomach, liver, and lungs from the natron solution. Dry, wrap, and place in their separate containers. Then place the wrapped body and organs back in the sealed unit and leave to dry for a further six weeks.

Finally, set the mummified body into a fitted sarcophagus, seal it with resin and beeswax, then set the sarcophagus in a tomb and leave it there for eternity.

* * *

In modern time, entire industries grew from public fascination around mummies. Beyond Hollywood movies and museum displays, mummies were considered medicinal magic. Ground mummy powder was sold for intestinal ailments, infertility, and internal bleeding control. A whole side-show industry offered mummification services to gullible people wanting their bodies preserved forever. Their makeshift mummies were hastily rushed, leaving their conned corpses sealed in ornate tombs and rotting away, with customers none the wiser.

In modern time, entire industries grew from public fascination around mummies. Beyond Hollywood movies and museum displays, mummies were considered medicinal magic. Ground mummy powder was sold for intestinal ailments, infertility, and internal bleeding control. A whole side-show industry offered mummification services to gullible people wanting their bodies preserved forever. Their makeshift mummies were hastily rushed, leaving their conned corpses sealed in ornate tombs and rotting away, with customers none the wiser.

Mummification morphed into modern times. Famous folks like Vladimir Lenin were stuffed and put on display in the Kremlin. Popes were preserved. So were saints and some scientists like Gottfried Knoche who was the inventor of embalming fluid. Evan Peron was encased in wax. Her life-like appearance led to the technology of plastination where water and fat are replaced by polymers that retain microscopic tissue properties. They don’t stink and are great for Body World’s traveling displays.

Little known to the western world is the ancient Buddhist monk practice of Sokushinbutsu. There are shadowy accounts of monks who were able to consciously mortify their flesh to death. It’s claimed Mahayana monks knew their time of death and prepared their bodies for preservation through a sparse diet of salt, nuts, seeds, roots, pine bark, and urushi tea. Their remains were set in the lotus position and sealed in a drying vat for three years…. their mummified bodies then adorned with gold… and put in a shrine on display.

Little known to the western world is the ancient Buddhist monk practice of Sokushinbutsu. There are shadowy accounts of monks who were able to consciously mortify their flesh to death. It’s claimed Mahayana monks knew their time of death and prepared their bodies for preservation through a sparse diet of salt, nuts, seeds, roots, pine bark, and urushi tea. Their remains were set in the lotus position and sealed in a drying vat for three years…. their mummified bodies then adorned with gold… and put in a shrine on display.

Sounds way over the top?

Well, I found this article from a Chinese website. It was published this month and proves the art of mummy making is anything but lost.

BEIJING — A revered Buddhist monk in China has been mummified and covered in gold leaf, a practice reserved for holy men in some areas with strong Buddhist traditions. The monk, Fu Hou, died in 2012 at age 94 after spending most of his life at the Chongfu Temple on a hill in the city of Quanzhou, in southeastern China, according to the temple’s abbot, Li Ren. The temple decided to mummify Fu Hou to commemorate his devotion to Buddhism — he started practicing at age 17 — and to serve as an inspiration for followers of the religion that was brought from the Indian subcontinent roughly 2,000 years ago.

BEIJING — A revered Buddhist monk in China has been mummified and covered in gold leaf, a practice reserved for holy men in some areas with strong Buddhist traditions. The monk, Fu Hou, died in 2012 at age 94 after spending most of his life at the Chongfu Temple on a hill in the city of Quanzhou, in southeastern China, according to the temple’s abbot, Li Ren. The temple decided to mummify Fu Hou to commemorate his devotion to Buddhism — he started practicing at age 17 — and to serve as an inspiration for followers of the religion that was brought from the Indian subcontinent roughly 2,000 years ago.

Immediately following his death, the monk’s body was washed, treated by two mummification experts, and sealed inside a large pottery jar in a sitting position, the abbot said. When the jar was opened three years later, the monk’s body was found intact and sitting upright with little sign of deterioration apart from the skin having dried out, Li Ren said. The body was then washed with alcohol and covered with layers of gauze, lacquer and finally gold leaf.

Immediately following his death, the monk’s body was washed, treated by two mummification experts, and sealed inside a large pottery jar in a sitting position, the abbot said. When the jar was opened three years later, the monk’s body was found intact and sitting upright with little sign of deterioration apart from the skin having dried out, Li Ren said. The body was then washed with alcohol and covered with layers of gauze, lacquer and finally gold leaf.

It was also robed, and a local media report said a glass case had been ordered for the statue, which will be protected with an anti-theft device. The local Buddhist belief is that only a truly virtuous monk’s body would remain intact after being mummified, local media reports said. “Monk Fu Hou is now being placed on the mountain for people to worship,” Li Ren said.

It was also robed, and a local media report said a glass case had been ordered for the statue, which will be protected with an anti-theft device. The local Buddhist belief is that only a truly virtuous monk’s body would remain intact after being mummified, local media reports said. “Monk Fu Hou is now being placed on the mountain for people to worship,” Li Ren said.

* * *

In my humble opinion… making mummies is far from a lost art. Monk Fu Hou is a phenomenal piece. He’s a guilded master of permanent human preservation and solid sample of scientific mummification.

I’d like to wake him and hear his views.

In this photo taken April 16, 2016, abbot Zhen Yu places a robe on the mummified body of revered Buddhist monk Fu Hou in Quanzhou city in southeastern China’s Fujian province. The monk, who died in 2012 at the age of 94, was prepared for mummification by his temple to commemorate his devotion to Buddhism. The mummifed remains were then treated and covered in gold leaf, a practice reserved for holy men in some areas with strong Buddhist traditions. (Chinatopix via AP) CHINA OUT ORG XMIT: XHG805