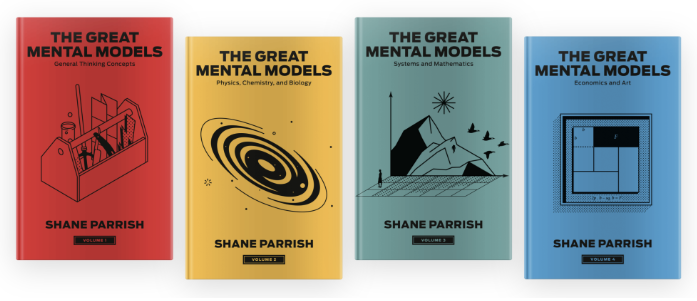

One trait setting humans apart from other species on this planet is thought. Next to our closest competitors, the octopus and the orangutan, humans far surpass at deep cognitive processing and complex problem solving. Recently, there’s a significant breakthrough in aiding human advancement to understand and know general reality concepts. It’s a four-volume tutorial called Critical Thinking — The Great Mental Models.

One trait setting humans apart from other species on this planet is thought. Next to our closest competitors, the octopus and the orangutan, humans far surpass at deep cognitive processing and complex problem solving. Recently, there’s a significant breakthrough in aiding human advancement to understand and know general reality concepts. It’s a four-volume tutorial called Critical Thinking — The Great Mental Models.

This is Part Two of a two-part series. You can read Part One here.

Shane Parrish is an internet thought leader and author of The Great Mental Models which is influenced by the wisdom of the late Charlie Munger. Shane also hosts Farnam Street and The Knowledge Project Podcast. His sites’ taglines are Master the Best of What Other People Have Already Figured Out and The Best Way to Make Intelligent Decisions.

Shane opens the Mental Models series with, “Education doesn’t prepare you for the real world.” He says, “The key to better understanding the world is to build a latticework of mental models.” Mental models, according to Shane Parrish, describe the way the world works in simplicity. They fundamentally, and without complication, shape how we think, how we understand, and how we form beliefs.

Largely subconscious, mental models operate beneath the surface. We’re not generally aware of them, and yet when we look at a problem, they’re the reason we consider some factors relevant and others irrelevant. They are how we infer causality, match patterns, and draw analogies. They are how we think and reason.

A mental model is a compression of how something works. Any idea, belief, or concept can be distilled down. Like maps, mental models reveal key information while ignoring the nonessential.

This post, Critical Thinking—The Great Mental Models Part Two, is long. Very long. It’s standard practice in blog writing to leave the conclusion to the end but, because of the length ahead of us, I brought the ending to the front. The entire material in this work is profound, but the conclusion is life-changing if you understand and apply it.

If you can’t spend the time reading this whole piece (7963 words), I want to leave you with just the core value. The key takeaway or your money’s worth.

The “secret” is there are two universal and invisible principles or concepts shaping everything we do and everything we are. They are above and beyond the macro cosmic and micro subatomic laws of physics. In fact, they give rise to the laws of physics.

These are axioms of pure existence, and these foundational pillars are a logarithmic compilation of all mental models combined. They’re deep currents, and they’re named compounding and entropy.

Compounding is the quiet drive of order behind exponential growth. It shows up in learning, habits, relationships, trust, and wealth. Small, smart actions—done consistently—don’t just add up, they multiply and escalate. It’s not about doing more… it’s about doing the right things over and over and over. Momentum builds and, across time, the results can be extraordinary.

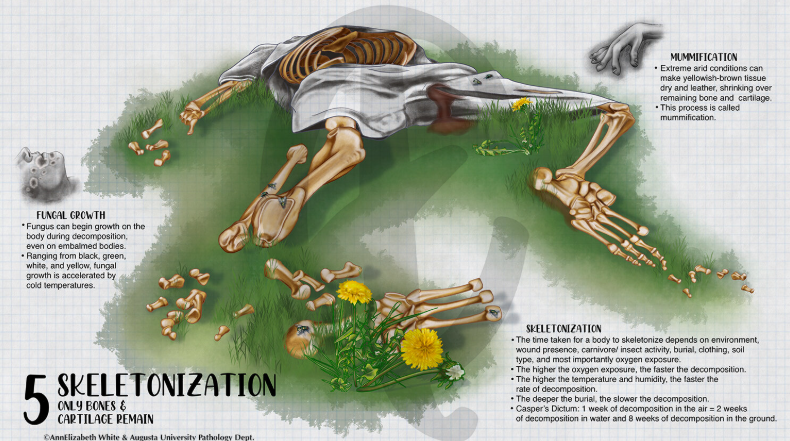

Entropy is the steady and relentless pull toward disorder. Left alone, anything—your health, clarity, systems, car, or relationships—naturally decays. Entropy reminds us that nothing stays strong without care, maintenance, and investment. Momentum decreases and, across time, the results will be devastating.

Progress, in all forms, requires continual infusion of energy, attention, and ongoing effort. Left unattended, all systems naturally decay to a state of equilibrium within their environment. Such is nature and, in the end, entropy always wins. Compounding simply delays or holds back entropy. In other words, both borrow on the arrow of time.

Both are mathematical certainties and behavioral truths. Together, these two fundamental and emergent principles explain how life works. How the universe operates. The true nature of reality.

Compounding is growth by care. Entropy is decay by neglect. In human terms, every meaningful system—personal or professional—either grows through steady investment or decays from inattention; a lack of maintenance and investment.

Understanding these two pilings helps you see why good habits matter, why trust is slow to earn but easy to lose, and why clarity, health, and success all require maintenance and investment. They’re not just scientific truths—they’re human and universal doctrines.

If you take away one fundamental thought from this entire article, it’s that compounding builds your future and entropy erodes it. Every choice you make, every mental model on the latticework you use, either contributes to one—or surrenders to the other.

Acquiring Wisdom

Wisdom isn’t about having all the answers—it’s about knowing how to ask better questions, see connections, and make sound judgments in the real world. This model reminds us that wisdom is built, not born. It compounds—accumulates like interest—through experience, reflection, failure, and pattern recognition. It’s not memorizing facts—it’s learning how to think clearly, act rightly, and live well. True wisdom connects theoretical knowledge to practical action (phronesis) with a moral compass pointing north.

The Map Is Not the Territory

A map is just a simplified model of reality—it’s not reality itself. This mental model warns us not to mistake our beliefs, theories, or assumptions for the real world. Just because something makes sense on paper doesn’t mean it plays out that way in life. Models, plans, and ideas are useful, but they’re only guides. The territory—real life—is always more complex and unpredictable. Stay grounded, stay curious, and never confuse the menu with the meal.

Circle of Competence

Know what you know—and know what you don’t. The Circle of Competence model is about honest self-awareness. We all have areas where our judgment is sound because we’ve put in the time and built real understanding. Step outside that circle, and your confidence can become dangerous. There’s no shame in saying “I don’t know.” In fact, it’s wise. Stay within your lane, expand it slowly, and don’t pretend to be an expert where you’re not.

Falsifiability

Falsifiability means a claim can be tested and proven wrong. If something can’t be challenged, it can’t be trusted. This model—at the core of scientific thinking—separates real knowledge from belief or opinion. If an idea is so vague or bulletproof that no evidence could disprove it, it’s not useful. Falsifiability keeps us honest. It demands clarity, evidence, and the courage to say, “Here’s what would make me change my mind.” Without it, we’re just guessing.

First Principles Thinking

First principles thinking means stripping an idea down to its bare bones—its fundamental truths—and building back up from there. Instead of reasoning by analogy (doing things just because others do), this model forces you to ask: “What’s actually true?” It’s how great thinkers break out of convention and find original solutions. When you ignore assumptions and start from scratch, you often discover that what’s “always been done” doesn’t have to be done that way at all.

Necessity and Sufficiency

Necessity and sufficiency help us think clearly about cause and effect. A necessary condition is something that must be true for an outcome to happen—but on its own, it might not be enough. A sufficient condition guarantees the outcome, all by itself. Confusing the two leads to sloppy thinking and bad conclusions. This model reminds us to ask: “Is this required? Is this enough?” It sharpens logic, avoids false assumptions, and keeps our reasoning on solid ground.

Second-Order Thinking

First-order thinking stops at the immediate result. Second-order thinking looks beyond—asking, “And then what?” It’s the difference between quick wins and long-term wisdom. Every action has consequences, and those consequences have consequences. Smart decisions come from thinking through the ripple effects, not just the splash. This model teaches you to pause, project, and consider the unintended fallout before you move.

Probabilistic Thinking

Probabilistic thinking means making decisions based on likelihood, not certainty. Life is full of unknowns, and this model helps you weigh outcomes by their chances instead of hoping for guarantees. It’s not about being right every time—it’s about being right often enough to win over time. Think in bets, not absolutes. Stack the odds in your favor, and you’ll make smarter choices in an unpredictable world.

Causation vs. Correlation

Just because two things happen together doesn’t mean one caused the other. Correlation is about patterns—causation is about proof. This model reminds us not to jump to conclusions just because A and B show up at the same time. The world is full of coincidences, hidden variables, and misleading trends. Smart thinkers dig deeper and ask, “What’s really driving this?” Confusing correlation for causation is one of the fastest ways to fool yourself—and others.

Inversion

Inversion flips the problem on its head. Instead of asking “How can I succeed?”, you ask “What would guarantee failure?” Then you avoid those pitfalls. It’s a mental model that clears the fog by looking at things backward. Often, it’s easier to spot what not to do than to figure out what to do. Want a good life? Avoid a bad one. Want clarity? Eliminate confusion. Inversion strips away illusion and gets you to the truth by taking the reverse route.

Occam’s Razor

Occam’s Razor says that the simplest explanation is usually the right one. When you’re faced with competing ideas, the one with the fewest assumptions often cuts closest to the truth. This model keeps you from overcomplicating things or falling for convoluted theories. Simplicity doesn’t mean shallow—it means clear, direct, and grounded. The more moving parts, the more chances something breaks. Trust simplicity unless complexity earns its place.

Hanlon’s Razor

Hanlon’s Razor reminds us: don’t attribute to malice what can be explained by ignorance or carelessness. People usually aren’t out to get you—they’re just distracted, misinformed, or doing their best with what they’ve got. This model cools the fire before it burns. It helps you respond with patience instead of paranoia. Most mistakes are human, not hostile. Don’t jump to conclusions—step back and give grace.

Relativity

Relativity teaches us that nothing stands alone—everything is judged in comparison to something else. Fast and slow, rich and poor, big and small—these are all relative terms. In real life, this means your perception depends on your perspective. What feels like a problem to you might look like a blessing to someone else. This model helps you zoom out, shift your frame of reference, and see situations more clearly. Change the lens, and the picture changes too.

Reciprocity

Reciprocity is the natural give-and-take that holds human relationships together. When someone does something for us, we feel a pull to return the favor—it’s wired into our psychology. This mental model reminds us that generosity often pays off, not because it’s a tactic, but because it builds trust and goodwill. But it cuts both ways: kindness breeds kindness, and hostility often invites it back. Play the long game—treat others well, and most will respond in kind.

Thermodynamics / Entropy

Thermodynamics—especially the second law—tells us that everything tends toward disorder unless energy is applied. In plain terms: if you don’t maintain it, it falls apart. That’s true for your health, your home, your relationships, even your mindset. Entropy—one half of the fundamental blocks of reality—is always at work, breaking things down. This model is a wake-up call to stay proactive. Keep investing effort where it matters, continually compound energy input, or watch things slowly decay. Nothing stays sharp without regular honing.

Inertia

Inertia is the tendency for things to stay as they are—whether that’s motion or stagnation. In the physical world, an object at rest stays at rest unless something pushes it. Same goes for your habits, routines, and momentum in life. This model explains why getting started is often the hardest part—and why it gets easier once you’re in motion. Use inertia to your advantage: build positive momentum and let it carry you forward. Just don’t wait for it to happen on its own.

Friction and Viscosity

Friction and viscosity are forces that resist movement—slowing things down, causing drag, and wasting energy. In life, friction shows up as bureaucracy, miscommunication, clutter, or anything that makes action harder than it needs to be. This model teaches us to spot those points of resistance and reduce them. Smoother systems—whether in work, habits, or relationships—move faster and go further. The less drag you create, the more flow you get.

Velocity

Velocity isn’t just about speed—it’s speed in a chosen direction. Going fast means nothing if you’re heading the wrong way. This model reminds us to align motion with purpose. In life and in work, progress is measured not by how busy you are, but by how efficiently you’re moving toward what matters. Direction first, speed second. Move with intent, not just momentum.

Leverage

Leverage is about getting outsized results from well-placed effort. In physics, a lever lets you move heavy objects with less force. In life, leverage shows up in tools, systems, people, capital, and ideas. It’s how small actions—done wisely—can create massive impact. This model teaches you to stop pushing harder and start pushing smarter. Find the right fulcrum, apply pressure, and let leverage do the heavy lifting.

Activation Energy

Activation energy is the initial push needed to get something started. In chemistry, it’s the spark that kicks off a reaction. In life, it’s the effort it takes to begin—whether that’s writing the first sentence, having a tough conversation, or getting out the door. This model reminds us that starting is often the hardest part, but once the reaction’s in motion, it gets easier. Lower the barrier to entry, and you’ll start more, finish more, and build real momentum.

Catalysts

Catalysts are agents that speed up change without being consumed in the process. In chemistry, they make reactions happen faster. In life, catalysts are people, tools, or ideas that accelerate progress without needing to take center stage. A mentor, a breakthrough insight, a moment of truth—these can all act as catalysts. This model teaches us to seek out what sparks change and makes things move quicker. The right catalyst can turn slow progress into a breakthrough.

Alloying

Alloying is the process of combining different elements to create something stronger than the parts alone—like mixing metals to form steel. In life, it’s a model for synergy. The right partnerships, skill sets, or ideas—when blended well—can enhance each other’s strengths and cancel out weaknesses. This teaches us that diversity, when unified with purpose, creates resilience and performance no single part could achieve alone. Stronger outcomes are forged, not found.

Evolution: Natural Selection and Extinction

Nature doesn’t reward the strongest—it rewards the most adaptable. Natural selection is the process where traits that help survival get passed on, while those that don’t fade away. In life, this means if you don’t adjust, you risk becoming irrelevant. Conditions change, environments shift, and if you stay rigid, you’ll get left behind. This model reminds us that extinction isn’t just about dinosaurs—it’s about people, businesses, and ideas that refuse to evolve. Adapt or disappear.

Evolution: Adaptation Rate and the Red Queen Effect

Adaptation rate is how fast you adjust to change—and in today’s world, speed matters. The Red Queen Effect, taken from evolutionary biology, says you have to keep running just to stay in place because everything around you is evolving too. If your rate of learning or improvement falls behind your environment, you lose ground. This model is a wake-up call: standing still is falling behind. Keep learning, keep adapting, or risk being outrun by the world around you.

Competition

Competition is the natural pressure that drives performance, innovation, and survival. In nature, species compete for limited resources. In life, we compete for time, attention, and opportunity. This model reminds us that competition can sharpen us—but it can also blind us if we’re not careful. Healthy competition pushes us to improve. Toxic competition distracts us from purpose. The key is to compete with integrity, learn from rivals, and never lose sight of your own path.

Ecosystem

An ecosystem is a web of interconnected parts that depend on each other to survive and thrive. In nature, every organism plays a role, and balance is key—disturb one part, and the whole system can shift. In life, it’s the same. Families, teams, businesses, even your daily habits form ecosystems. This model teaches us to think holistically. Nothing exists in isolation, so when you change one piece, you affect the whole. Healthy systems depend on healthy relationships between their parts.

Niches

A niche is a specialized role or space where something thrives with little competition. In biology, species survive by finding a niche that fits their traits. In life, it’s about discovering where your unique skills, interests, and value align with real need. This model reminds us that you don’t have to be everything to everyone—you just need to be the right fit in the right place. Success often comes from narrowing your focus, not widening it. Find your niche, and own it.

Self-Preservation

Self-preservation is nature’s default setting—an instinct hardwired into every living thing to survive and avoid harm. In people, it shows up as caution, defensiveness, and sometimes resistance to change. This model helps us understand why fear and avoidance are such strong forces in behavior. It’s not weakness—it’s biology. But when self-preservation goes unchecked, it can hold you back from growth. The key is to recognize the instinct, respect its purpose, and choose when to override it in favor of something greater.

Replication

Replication is the biological engine of continuity—life passes itself on by copying. In nature, it’s how genes survive. In human life, replication shows up in behaviors, beliefs, habits, and ideas that get repeated and passed down. This model reminds us that what we do doesn’t stop with us—it gets mirrored by others, especially in families, cultures, and organizations. So be mindful of what you replicate. What you model, others repeat. And what you repeat, you become.

Cooperation

Cooperation is nature’s strategy for shared survival—organisms that work together often do better than those that go it alone. In human life, the same holds true. We get further when we collaborate, build trust, and create mutual value. This model reminds us that strength doesn’t always come from dominance—it often comes from unity. Whether in families, teams, or communities, cooperation multiplies what individuals can do alone. Evolution favors those who know when to compete—and when to join forces.

Dunbar’s Number

Dunbar’s Number is the idea that humans can only maintain about 150 meaningful relationships at a time. Beyond that, things start to break down—trust fades, communication weakens, and social bonds stretch too thin. This model reminds us that our brains are wired for connection, but only up to a point. In a world pushing constant networking and digital “friends,” Dunbar’s Number is a reality check: depth matters more than volume. Focus on the relationships that truly count.

Hierarchical Organization

Hierarchy is nature’s way of creating order from complexity. From cells to societies, systems organize themselves into layers—each with roles, responsibilities, and flow of control. In life, we see it in families, companies, governments—even in our brains. This model reminds us that structure isn’t just control—it’s coordination. Well-built hierarchies help things run smoothly; broken ones breed confusion and waste. The key is to understand where you fit, how information flows, and when to challenge the chain for the greater good.

Incentives

Incentives are the invisible forces that drive behavior. People don’t do what you expect—they do what they’re rewarded for. This model teaches us to look beneath actions and ask, “What’s the real motive?” Whether it’s money, recognition, fear, or purpose, incentives shape choices more than logic does. Get the incentives right, and the behavior follows. Get them wrong, and even good people will make bad decisions. If you want to change the outcome, change what gets rewarded.

Tendency to Minimize Energy Output

Nature runs on efficiency—living things instinctively look for the path of least resistance. This tendency to minimize energy output is why we form habits, avoid effort, and stick to routines—even when better options exist. It’s a survival trait, not a flaw. But left unchecked, it can lead to laziness and stagnation. This model reminds us that while conserving energy has its place, real growth often comes from doing the hard thing. Don’t confuse ease with wisdom.

Feedback Loops

Feedback loops are cycles where a system’s output feeds back into itself, shaping future behavior. Positive loops amplify change—like compounding growth or viral ideas. Negative loops stabilize systems—like a thermostat keeping a room at the right temperature. This model helps us see that nothing happens in isolation; actions have consequences that loop back. Understanding feedback loops lets you spot runaway effects, self-corrections, and when to intervene. If you want to master systems, watch what they feed themselves.

Equilibrium

Equilibrium is the state where opposing forces are balanced and a system settles into stability. In nature, markets, and even our bodies, systems constantly shift to find this balance. But equilibrium doesn’t mean stillness—it’s dynamic, always adjusting to change. This model reminds us that sustainable success isn’t about extremes—it’s about finding the point where things hold steady under pressure. When something feels off, ask: what’s throwing it out of balance—and what would restore it?

Bottlenecks

A bottleneck is the one point in a system that slows everything else down. It doesn’t matter how fast the other parts run—if one part can’t keep up, the whole system chokes. This model teaches us to stop throwing effort everywhere and instead focus on the constraint. Fix the bottleneck, and you free up flow. Whether it’s a person, a process, or a habit, identifying and improving the slowest point is how you unlock real progress.

Scale

Scale is about how things change when they get bigger—or smaller. What works at one level often breaks at another. A system that runs smoothly with five people might collapse with fifty. This model reminds us that size brings complexity, and growth isn’t always a win if it outpaces your ability to manage it. Thinking in scale helps you design things that work not just now, but later. Plan for growth—or be crushed by it.

Margin of Safety

Margin of safety is the buffer between what you expect to happen and what could go wrong. It’s the room to breathe, the space to absorb shocks. Engineers build it into bridges, investors build it into deals—and wise people build it into their lives. This model reminds us that life is uncertain, and pushing things to the limit leaves no room for error. Success is not just about being right—it’s about having a cushion when you’re wrong.

Churn

Churn is the constant turnover within a system—customers leave, employees quit, ideas fade. It’s a sign of friction, dissatisfaction, or simply natural change. This model reminds us that nothing lasts forever, and if you’re not creating value consistently, people move on. High churn drains energy and momentum. To reduce it, listen better, serve better, and adapt faster. Stability comes not from holding on tighter, but from giving people a reason to stay.

Algorithms

Algorithms are step-by-step instructions for solving a problem or making a decision. They’re how machines think—but they also reflect how we operate. Habits, checklists, routines—they’re all human algorithms. This model reminds us that good systems reduce guesswork and create reliable outcomes. But be careful: if your algorithm is based on bad logic or broken assumptions, it’ll still run—just in the wrong direction. Build smart processes, and they’ll carry you further than willpower alone.

Complex Adaptive Systems

Complex adaptive systems are made of many parts that interact, learn, and evolve over time—like ecosystems, economies, or the human brain. You can’t control them with simple rules because they change as they go. This model reminds us that in complex systems, cause and effect aren’t always obvious, and small changes can have big, unpredictable outcomes. The smart move isn’t to control—it’s to observe, adapt, and respond. In these systems, flexibility beats force every time.

Critical Mass

Critical mass is the tipping point—the moment when enough energy, people, or momentum builds up to trigger a lasting change. Before that, it’s all effort with little visible result. But hit critical mass, and things take off—like a fire catching or a movement spreading. This model reminds us to be patient in the early stages and persistent through slow progress. Most breakthroughs don’t come gradually—they come suddenly, after you’ve crossed the line where everything shifts.

Emergence

Emergence is when the whole becomes more than the sum of its parts. In complex systems, simple pieces interact in ways that create unexpected patterns—like birds flocking, traffic flowing, or consciousness arising from neurons. You can’t predict the outcome just by studying the pieces. This model reminds us that some truths only reveal themselves at scale, through interaction. Pay attention to how things connect—not just what they are—and you’ll start to see the bigger picture take shape.

Chaos Dynamics

Chaos dynamics shows us that systems can be highly sensitive—tiny changes in starting conditions can lead to wildly different outcomes. It’s why weather is hard to predict and why life rarely goes in a straight line. This model reminds us that not all unpredictability is random—chaos has patterns, but they’re complex. In a chaotic world, control is limited, but awareness is power. Focus on what you can influence, stay flexible, and don’t mistake chaos for failure—it’s often just how change begins.

Irreducibility

Irreducibility means some things can’t be broken down into simpler parts without losing their essence. You can dissect a poem word by word, but you’ll miss the meaning. In complex systems—like human behavior, ecosystems, or cultures—some truths only emerge when you look at the whole. This model reminds us not everything fits in a neat box or formula. Sometimes, understanding comes not from analysis, but from stepping back and seeing the full picture.

The Law of Diminishing Returns

The Law of Diminishing Returns says that after a certain point, adding more effort, time, or resources gives you less and less back. The first push makes a big difference—the tenth, not so much. This model reminds us that more isn’t always better. It helps you know when to stop, pivot, or redirect your energy. Productivity, progress, even pleasure all have a sweet spot. Know when you’ve reached it, or risk wasting effort that no longer pays off.

Distributions

Distributions show how things are spread out—like income, height, or success. Most people think in averages, but reality isn’t always neat. Some things follow a bell curve, where most results cluster in the middle. Others follow a power law, where a small few account for most of the outcome—like wealth, talent, or viral content. This model reminds us to look beyond the average. Outliers matter, and how something is distributed often matters more than how much there is.

Compounding

Compounding is the quiet force that turns small, consistent actions into massive results over time. Whether it’s money, knowledge, habits, or trust—when gains build on top of gains, growth becomes exponential. This model reminds us that the biggest rewards don’t come from big moves, but from steady, repeated effort. Start early, stay consistent, and be patient. Compounding doesn’t look like much at first—until it suddenly looks like everything. It’s the second half of the foundation of reality—of existence.

Network Effects

Network effects happen when each new user or connection makes a system more valuable for everyone else. It’s why social media platforms, marketplaces, and ideas can grow so fast—because value scales with participation. The more people join, the better it gets. This model reminds us that momentum attracts more momentum. If you can build something people want to connect with, growth feeds on itself. But it cuts both ways—if value drops, people leave, and the network unravels just as fast.

Sampling

Sampling is the practice of studying a smaller group to understand the larger whole. Done right, it saves time and resources while still revealing useful insights. But if your sample is too small, biased, or unrepresentative, your conclusions will be off. This model reminds us to be careful about what we’re basing decisions on. Don’t trust one opinion to speak for many, and don’t judge the whole based on a flawed piece. The quality of your sample shapes the truth you see.

Randomness

Randomness is the role of chance in outcomes—those unpredictable events that don’t follow a clear pattern. We like to believe everything happens for a reason, but sometimes luck, timing, or pure chance play a bigger role than skill or planning. This model reminds us to stay humble. Success isn’t always earned, and failure isn’t always deserved. Recognizing randomness helps us avoid false certainty, judge outcomes more fairly, and make better decisions in an uncertain world.

Pareto Principle

The Pareto Principle—also known as the 80/20 Rule—says that a small number of inputs often produce the majority of results. In business, 20% of customers generate 80% of profits. In life, a few key habits shape most of your outcomes. This model teaches us to focus on what matters most—the vital few instead of the trivial many. Don’t spread yourself thin. Find the high-impact levers and pull them hard.

Regression to the Mean

Regression to the mean is the tendency for extreme results—good or bad—to drift back toward average over time. A superstar performance or a sudden failure often isn’t permanent—it’s part of a natural swing. This model reminds us not to overreact to highs or lows. Success isn’t always skill, and failure isn’t always flaw. Given time, most things settle back to normal. Keep a level head, and don’t chase or fear the extremes—they rarely last.

Multiplying by Zero

Multiplying by zero means that no matter how much effort, talent, or resources you apply, one critical failure can wipe it all out. In math, any number times zero is still zero. In life, it’s forgetting a key step, ignoring a risk, or cutting the wrong corner. This model reminds us that some mistakes are non-negotiable—they nullify everything else. Identify your zeros—whether it’s trust, safety, or health—and protect them at all costs.

Equivalence

Equivalence means two things are equal in value, effect, or outcome—even if they look different on the surface. In math, it’s about balance in equations. In life, it shows up when different paths lead to the same result, or when one trade-off cancels out another. This model helps us think clearly about fairness, options, and alternatives. It reminds us that sometimes the best choice isn’t about what’s better, but about what’s equal in impact—even if it takes a different shape.

Order and Magnitude

Order of magnitude is about scale—how big something really is in relation to something else. It’s the difference between a hundred, a thousand, and a million. This model reminds us that not all numbers—and not all problems—are created equal. Small improvements might help, but some challenges or opportunities are ten, a hundred, or a thousand times more impactful. Thinking in orders of magnitude keeps us from treating big issues like small ones—and helps us spot where the real leverage lies.

Surface Area

Surface area is the amount of space exposed to outside forces—and in life, more exposure means more risk or opportunity. A business with more customers has more potential, but also more to manage. A public figure has more influence, but more scrutiny. This model reminds us that the bigger your surface area, the more interactions you face—for better or worse. Be mindful of what you expose, what you protect, and how you design your life or work to handle the contact points.

Global and Local Maxima

Local maxima are points where you’ve hit a high spot—but not the highest possible one. You might feel successful, but there’s something better out there. The global maximum is the true peak—the best outcome available. This model reminds us that settling too soon can trap us in comfort zones. Sometimes, to reach something greater, you have to leave what’s “good enough” and risk a temporary drop. Growth often means letting go of the hill you’re on to climb the mountain you can’t yet see.

Scarcity

Scarcity is the basic economic reality that we can’t have everything—time, money, energy, and resources are limited. This model reminds us that every choice comes with a trade-off. When something is scarce, it becomes valuable—not just in price, but in attention and effort. Scarcity sharpens focus and forces prioritization. You can’t do it all, so choose what matters most. The wise learn to spend their limited resources where the return is truly worth it.

Supply and Demand

Supply and demand is the engine that drives value. When something is scarce and lots of people want it, its value rises. When there’s too much of something and not enough interest, the value drops. This model explains prices, trends, even attention. It reminds us that value isn’t fixed—it’s shaped by desire and availability. Whether you’re selling a product, sharing an idea, or building a career, understanding supply and demand helps you play the game wisely.

Game Theory

Game theory is the study of how people make decisions when their outcomes depend on what others do. Life is full of games—some cooperative, some competitive—and every move you make affects others, just as their moves affect you. This model reminds us to think strategically: What are the incentives? What’s the other side likely to do? And how do I respond? Winning often isn’t about beating others—it’s about understanding the game you’re playing and choosing the smartest moves.

Optimization

Optimization is about finding the most efficient, effective way to achieve a goal—getting the best outcome with the least waste. It’s not just doing things right—it’s doing the right things better. This model reminds us to focus on what really moves the needle, cut what doesn’t, and fine-tune systems until they run smooth. But beware: over-optimizing can make you brittle. Leave room for flexibility. The best systems balance performance with resilience.

Trade-Offs

Trade-offs are the reality that you can’t have it all—choosing one thing means giving up something else. Every decision comes with a cost, whether it’s time, money, energy, or opportunity. This model reminds us to think in terms of value, not just outcomes. What are you gaining—and what are you sacrificing to get it? Wise choices come from knowing what’s truly worth it and being honest about what you’re willing to let go.

Specialization

Specialization is focusing on what you do best so you can do it better, faster, and more efficiently. In economies, it leads to higher productivity. In life, it helps you stand out and create more value. This model reminds us that trying to do everything usually means doing nothing well. Focus breeds excellence. The key is to specialize deeply, but stay flexible enough to adapt when the world changes around you.

Interdependence

Interdependence means we don’t succeed alone—our actions, choices, and outcomes are linked with others. In economies, ecosystems, and everyday life, we rely on networks of people, systems, and resources to function. This model reminds us that strength comes not just from independence, but from healthy connection. The smartest moves often come from understanding how your success supports—and depends on—the success of those around you.

Efficiency

Efficiency is about getting more done with less—less time, less effort, less waste. It’s the art of streamlining, of cutting out what doesn’t matter so you can focus on what does. In systems, it boosts output. In life, it frees up energy. This model reminds us that being busy isn’t the same as being effective. True efficiency is doing the right things, the right way, at the right time—without burning out or bogging down.

Debt

Debt is borrowing from the future to solve a problem today—whether it’s money, time, energy, or trust. It can be a smart tool when used wisely, but dangerous when ignored. This model reminds us that every debt comes with a cost, and eventually, it must be repaid—often with compounded interest. Financially or otherwise, living beyond your means catches up. Use debt strategically, not carelessly, and always ask: “Can I afford the payback later for the relief I get now?”

Monopoly and Competition

Monopoly and competition are two ends of the economic playing field. In a monopoly, one player controls the game—setting prices, limiting choices, and reducing innovation. In competition, many players push each other to improve, lower costs, and create value. This model reminds us that healthy competition benefits everyone, while unchecked monopolies can stall progress. Whether in business or ideas, the sweet spot is often a balance—enough rivalry to drive growth, but not so much it destroys value.

Externalities

Externalities are the hidden side effects—costs or benefits of an action that affect others who didn’t choose to be involved. Pollution is a classic negative externality; a well-kept garden that raises neighborhood property values is a positive one. This model reminds us that our choices ripple outward, often in ways we don’t see. Smart thinking—and smart systems—account for these ripple effects. Ignoring externalities may save effort now but creates bigger problems later.

Creative Destruction

Creative destruction is the process where old systems, ideas, or industries break down to make way for the new. It’s how progress happens—painful, messy, but necessary. Think of how streaming wiped out video stores or how smartphones replaced dozens of other gadgets. This model reminds us that growth often requires letting go. What works today won’t last forever, and clinging to the past can hold you back. Destruction, called entropy, clears space for innovation—if you’re brave enough to build again.

Gresham’s Law

Gresham’s Law says that “bad money drives out good.” When both are in circulation, people tend to spend the lower-quality currency and hoard the more valuable one. But it’s more than just money—it applies to ideas, behavior, and systems. Low-quality input often pushes out the high-quality stuff unless there’s a system to protect it. This model reminds us to watch for decay: when shortcuts, noise, or dishonesty become the norm, value quietly disappears. If you want quality to thrive, you have to defend it.

Bubbles

Bubbles form when prices or expectations rise far beyond what something is truly worth—fueled by hype, fear of missing out, and irrational optimism. They feel great while they’re growing, but they always pop. This model reminds us that when something seems too good to be true, it probably is. Whether it’s in markets, trends, or beliefs, watch for signs of inflated value with no solid foundation. Don’t get swept up—stay grounded in reality when everyone else is floating away.

Audience

Audience is the group you’re trying to reach, move, or influence—and understanding them is everything. Whether you’re writing, speaking, designing, or leading, the message only matters if it lands. This model reminds us that communication isn’t about what you say—it’s about what others hear. Great creators don’t just express themselves—they tune into who they’re speaking to, what that audience values, and how best to connect. Know your audience, and you know your impact.

Genre

Genre is the shared language between creator and audience—a set of expectations that helps people understand what kind of experience they’re about to have. It’s the familiar shape that frames the story, message, or product. This model reminds us that while originality matters, clarity comes first. Working within genre isn’t limiting—it’s guiding. Master the rules before you break them, and you’ll earn trust before you surprise.

Contrast

Contrast is what makes things stand out—light against dark, silence after noise, calm before chaos. It’s not just about difference—it’s about meaning through difference. In art, writing, storytelling, and even life, contrast grabs attention and creates emotional impact. This model reminds us that without contrast, everything blends into the background. To make a point, highlight the opposite. To show change, show what came before. Contrast sharpens the edges of truth.

Framing

Framing is how you shape the way something is seen—what you choose to highlight, what you leave out, and the context you wrap it in. The same facts can feel inspiring or terrifying depending on how they’re presented. This model reminds us that perception is powerful. The frame often is the message. In communication, leadership, or art, it’s not just what you show—it’s how you show it that makes all the difference.

Rhythm

Rhythm is the pattern of movement, sound, or flow that gives structure and energy to an experience. In music, it’s the beat. In writing, it’s pacing. In life, it’s the cadence of work, rest, and renewal. This model reminds us that rhythm creates momentum, holds attention, and makes things feel alive. Too fast, and you lose clarity. Too slow, and you lose interest. Find the right rhythm, and everything starts to move in sync.

Melody

Melody is the thread that ties everything together—it’s the part you remember, the part that moves you. In music, it’s the tune. In storytelling, it’s the emotional arc. In communication, it’s the central idea that rises above the noise. This model reminds us that people connect to what flows, not just what’s said. A strong melody gives structure meaning and feeling. When form and function meet emotion, that’s when your message truly sings.

Representation

Representation is how we use symbols, images, words, or ideas to stand in for something else—making the invisible visible, or the complex understandable. It’s how we tell stories, explain truths, and make meaning. But every representation is a choice—and every choice filters reality. This model reminds us to look deeper: what’s being shown, what’s being left out, and why? Powerful representation isn’t just about accuracy—it’s about intention, clarity, and connection.

Balance

Balance is the art of holding tension between opposing forces—light and dark, motion and stillness, detail and simplicity—so that nothing overwhelms the whole. In design, it creates harmony. In life, it creates stability. This model reminds us that more isn’t always better and that strength often comes from restraint. True balance isn’t static—it’s dynamic, responsive, and alive. When everything is in its right place, you feel it—even if you can’t explain why.

Plot

Plot is the structure that turns events into a story—it’s not just what happens, but why it matters. A good plot gives direction, builds tension, and leads the audience through change. It’s the shape of transformation, the path from problem to resolution. This model reminds us that meaning doesn’t come from motion alone—it comes from movement with purpose. Whether in storytelling, strategy, or life, plot is what gives action a reason to exist.

Character

Character is the human core of every story—the person through whom we experience conflict, growth, and truth. But it’s more than a role; it’s what someone wants, what they struggle with, and how they change. This model reminds us that great characters aren’t perfect—they’re real. In storytelling and in life, character is revealed through choices, especially under pressure. Plot drives the story, but character gives it soul.

Setting

Setting is the world your story lives in—the time, place, and atmosphere that shape everything that happens. It’s not just background—it’s part of the story’s DNA. A well-crafted setting creates mood, builds tension, and gives context to character and plot. This model reminds us that where something happens is just as important as what happens. The more real the world, the more the story resonates. Setting grounds imagination in something we can feel.

Subtext

Subtext is what’s really being said beneath the surface—what characters mean, feel, or want without directly stating it. It’s the tension between words and truth, the space where deeper meaning lives. In life and storytelling, subtext is often more powerful than dialogue. This model reminds us to listen not just to what’s said, but to what’s unsaid. When you master subtext, you don’t just tell a story—you reveal the truth behind it.

Performance

Performance is the act of bringing something to life in front of others—whether it’s a story, a skill, or your true self. It’s where preparation meets presence, where the private becomes public. This model reminds us that how you deliver something matters as much as what you deliver. Tone, timing, energy, and authenticity all shape the experience. A powerful performance doesn’t just inform—it moves, connects, and stays with people long after the moment has passed.

Summation

The Great Mental Models series by Shane Parrish, and influenced by Charlie Munger, gives us a powerful toolbox for thinking—a latticework pulled from physics, biology, math, systems, economics, and the creative arts. In this post, we broke down each model into a clear, one-paragraph explanation using everyday language and a grounded, human voice. These models aren’t abstract theories—they’re timeless ways to see the world more clearly, make better decisions, and live with greater purpose.

Whether you’re writing, leading, teaching, or just trying to navigate life wisely, these mental models are the bridges between knowing and understanding, and between seeing and doing. Used well, they help us make sense of complexity—and turn insight into action.

Conclusion

There are two universal and invisible principles or concepts shaping everything we do and everything we are. They are above and beyond the macro cosmic and micro subatomic laws of physics. These are axioms of pure existence, and these foundational pillars are the sum of all mental models combined. They’re deep currents, and they’re named compounding and entropy.

Compounding is the quiet drive behind exponential growth. It shows up in learning, habits, relationships, trust, and wealth. Small, smart actions—done consistently—don’t just add up, they multiply. It’s not about doing more… it’s about doing the right things over and over and over. Momentum builds and, across time, the results can be extraordinary.

Entropy is the steady and relentless pull toward disorder. Left alone, anything—your health, clarity, systems, car, or relationships—naturally decays. Entropy reminds us that nothing stays strong without care, maintenance, and investment. Momentum decreases and, across time, the results will be devastating.

Progress, in all forms, requires continual infusion of energy, attention, and ongoing effort. Left unattended, all systems naturally decay to a state of equilibrium within their environment. Such is nature and, in the end, entropy always wins. Compounding simply delays or holds back entropy. In other words, both borrow on time.

Together, these two fundamental principles and concepts explain how life works. How the universe operates. The true nature of reality.

Compounding rewards discipline. Entropy punishes neglect. In human terms, every meaningful system—personal or professional—either grows through steady investment or crumbles from inattention; a lack of maintenance and investment.

Understanding these two pilings of reality helps you see why good habits matter, why trust is slow to earn but easy to lose, and why clarity, health, and success all require maintenance and investment. They’re not just scientific truths—they’re human doctrines.

If you takeaway one fundamental thought from this post, it’s that compounding builds your future and entropy erodes it. Every choice you make, every mental model on the latticework you use, either contributes to one—or surrenders to the other.

It’s the yin and the yang.

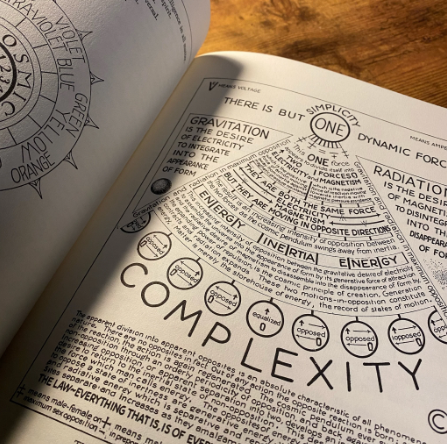

There’s something about certain stories that just won’t go away—fascinating stories buried beneath mounds of mainstream mockery, half-truths/half-fakes, and bygone wisdom or outright quackery. The story of Walter Russell is one of them. He was either the greatest misunderstood mind of the 20th century… or a deluded madman darkly cloaked in cosmic language and boldly dressed in narcissistic self-importance. I’ve come to see Russell more as a forgotten genius rather than a friggin’ nut. But then, I’ve been wrong before, and I’ll be wrong again.

There’s something about certain stories that just won’t go away—fascinating stories buried beneath mounds of mainstream mockery, half-truths/half-fakes, and bygone wisdom or outright quackery. The story of Walter Russell is one of them. He was either the greatest misunderstood mind of the 20th century… or a deluded madman darkly cloaked in cosmic language and boldly dressed in narcissistic self-importance. I’ve come to see Russell more as a forgotten genius rather than a friggin’ nut. But then, I’ve been wrong before, and I’ll be wrong again.