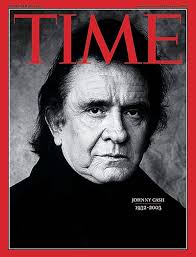

Johnny Cash was a brilliant musician. Singer. Performer. And masterful songwriter. Johnny Cash condensed high concept ideas into short, resonating stories – ripping people’s hearts in four or five stanzas – that stayed in millions of ears and memories. Big River was his best-told story. And he played it when inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

Johnny Cash was a brilliant musician. Singer. Performer. And masterful songwriter. Johnny Cash condensed high concept ideas into short, resonating stories – ripping people’s hearts in four or five stanzas – that stayed in millions of ears and memories. Big River was his best-told story. And he played it when inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

A writer friend recently ranted about working with a Grammar Nazi. Wait – How the hell does that relate to the man in black? And why are these opening paragraphs so disjointed? Stick with me.

“Jesus Christ! My editor’s gagging my friggin’ voice.” Frustration in her email zinged through me.

“Know it.” I keyed back.

“Who says we can’t start a sentence with ‘And’?” She pounded. “We’re crime-thriller writers, for God’s sakes. Not tryin’ for a Pulitzer Prize in English Lit.”

“Who says we can’t start a sentence with ‘And’?” She pounded. “We’re crime-thriller writers, for God’s sakes. Not tryin’ for a Pulitzer Prize in English Lit.”

I nodded. “Remember what King says – ‘Grammar don’t wear no coat ‘n tie’.” (Stephen King’s advice in On Writing).

‘Yep. Holding m’ground.” She breathed out. “It’s my story and I’m stickin’ to tellin’ it my way.”

“Good for you!” I pecked, thinking So much of what makes a great story is the way it’s told. Take songwriting. There’s not a lick of good grammar in most songs and some songs are timeless stories. Like Big River. I bet novelists can learn a lot from songwriters.

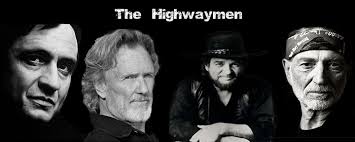

That night I kicked back with (a) glass of wine, headphones on, rockin’ to The Highwaymen – Live at Nassau Coliseum (1985). Their encore was Big River.

The Highwaymen: Willie Nelson. Waylon Jennings. Kris Kristopherson. And Johnny Cash. All great musicians. Singers. Performers. And masterful songwriters.

The Highwaymen: Willie Nelson. Waylon Jennings. Kris Kristopherson. And Johnny Cash. All great musicians. Singers. Performers. And masterful songwriters.

But Johnny Cash was a one-of-a-kind musical figure, quintessentially American; able to identify with the outlaw, and vice-versa – craggy, with a voice unlike anyone’s. Waylon & Willie worshiped him. Kris Kristofferson wrote “He’s a poet, he’s a picker, he’s a prophet, he’s a pusher, he’s a pilgrim, and he’s a preacher.”

Johnny Cash’s masterpiece, Big River, was cut in 1958 and topped the charts. It has everything in one story.

Now I taught the weeping willow how to cry

And I showed the clouds how to cover up a clear blue sky

And the tears that I cried for that woman are gonna flood you Big River

Then I’m gonna sit right here until I die

I met her accidentally in St. Paul, Minnesota

And it tore me up every time I heard her drawl, southern drawl

Then I heard my dream was back downstream cavortin’ in Davenport

And I followed you Big River when you called

Then you took me to St. Louis later on down the river

A freighter said she’s been here but she’s gone, boy, she’s gone

I found her trail in Memphis but she just walked up the bluff

She raised a few eyebrows and then she went on down alone

Now, won’t you batter down by Baton Rouge, River Queen, roll it on

Take that woman on down to New Orleans, New Orleans

Go on, I’ve had enough, dump my blues down in the gulf

She loves you, Big River, more than me

Now I taught the weeping willow how to cry, cry, cry

And I showed the clouds how to cover up a clear blue sky

And the tears that I cried for that woman are gonna flood you Big River

Then I’m gonna sit right here until I die

Re-reading the lyrics – even when I thought I understood the words – “then I heard my dream was back downstream cavortin’ in Davenport ” got me. Like, how good is that?

Re-reading the lyrics – even when I thought I understood the words – “then I heard my dream was back downstream cavortin’ in Davenport ” got me. Like, how good is that?

Big River is a study in storytelling. High concept in a timeless, global theme of lost love. Slots into a romance genre – the largest commercial fiction market. Opens with an emotional prologue. Sharp hook in beginning act; builds tension in middle; ends in the third act by answering the central story question.

Big River introduces protagonist and antagonist in the opening line of the first scene. There’s desire and conflict; hope and despair. Stays in first person point-of-view. Past tense. Every word – Every line – Every paragraph advances the story, following a forlorn search from the Mississippi’s top to its bottom – in the heart of American country music.

Big River introduces protagonist and antagonist in the opening line of the first scene. There’s desire and conflict; hope and despair. Stays in first person point-of-view. Past tense. Every word – Every line – Every paragraph advances the story, following a forlorn search from the Mississippi’s top to its bottom – in the heart of American country music.

Big River has implied dialogue. Adjectives that work. Not a useless, stinky-little adverb in sight. Beats become scenes; scenes sequence acts. There’s subplot and subtext. Every word counts. Setting is vivid… but time frame is everywhere in the past two hundred years. And characters aren’t named – but they’re strongly identifiable – because they could be you and me.

There’s not a lick of good grammar in Big River. Punctuation’s the shits!! There’s run-ons and cut-offs and pretty much everything a Grammar Nazi could hate.