Carl Sagan was one of the Twentieth Century’s great critical thinkers. His peers called Sagan the patron saint of reason and the master of scientific balance between blind belief, skepticism, questioning, and openness. Carl Sagan had the chops to back it up. He was a cosmologist, astrophysicist, philosopher, humanist, and prolific author as well as being the architect behind SETI — the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence. Sagan was also good at detecting bullshit.

Carl Sagan was one of the Twentieth Century’s great critical thinkers. His peers called Sagan the patron saint of reason and the master of scientific balance between blind belief, skepticism, questioning, and openness. Carl Sagan had the chops to back it up. He was a cosmologist, astrophysicist, philosopher, humanist, and prolific author as well as being the architect behind SETI — the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence. Sagan was also good at detecting bullshit.

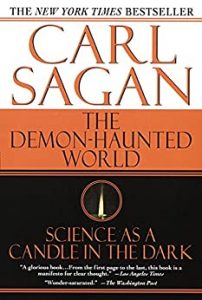

I just read Carl Sagan’s book The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark. It was published in 1996 shortly before Sagan’s untimely death from myelodysplasia. In it, he debunks superstition, some organized religion beliefs, psychics, sorcery, faith healing, UFOs, witchcraft, and demons — especially the fire-breathing dragon in his garage. One of Sagan’s chapters is The Fine Art of Baloney Detection. He was profanity-correct twenty-five years ago. Today, we know he’d call it “Bullshit”.

In The Demon-Haunted World, Carl Sagan takes a hard run at paid product endorsements by unscrupulous scientists who “betray contempt for the intelligence of their customers and introduce an insidious corruption of popular attitudes about scientific objectivity”. Sagan also predicted the rise of fake news and the down-slide of political ethics and honesty. It made me wonder what he’d say about Trump.

In The Demon-Haunted World, Carl Sagan takes a hard run at paid product endorsements by unscrupulous scientists who “betray contempt for the intelligence of their customers and introduce an insidious corruption of popular attitudes about scientific objectivity”. Sagan also predicted the rise of fake news and the down-slide of political ethics and honesty. It made me wonder what he’d say about Trump.

Carl Sagan said that “through their training, scientists are equipped with a baloney (bullshit) detection kit — a set of cognitive tools and techniques that fortify the mind against the penetration of falsehoods”. Here is a list of what’s inside Carl Sagan’s bullshit detection kit:

1. Wherever possible there must be independent confirmation of the “facts.”

2. Encourage substantive debate on the evidence by knowledgeable proponents of all points of view.

3. Arguments from authority carry little weight — “authorities” have made mistakes in the past. They will do so again in the future. Perhaps a better way to say it is that in science there are no authorities; at most, there are experts.

4. Spin more than one hypothesis. If there’s something to be explained, think of all the different ways in which it could be explained. Then think of tests by which you might systematically disprove each of the alternatives. What survives, the hypothesis that resists disproof in this Darwinian selection among “multiple working hypotheses,” has a much better chance of being the right answer than if you had simply run with the first idea that caught your fancy.

5. Try not to get overly attached to a hypothesis just because it’s yours. It’s only a way station in the pursuit of knowledge. Ask yourself why you like the idea. Compare it fairly with the alternatives. See if you can find reasons for rejecting it. If you don’t, others will.

6. Quantify. If whatever it is you’re explaining has some measure, some numerical quantity attached to it, you’ll be much better able to discriminate among competing hypotheses. What is vague and qualitative is open to many explanations. Of course there are truths to be sought in the many qualitative issues we are obliged to confront, but finding them is more challenging.

7. If there’s a chain of argument, every link in the chain must work (including the premise) — not just most of them.

8. Occam’s Razor. This convenient rule-of-thumb urges us when faced with two hypotheses that explain the data equally well to choose the simpler.

9. Always ask whether the hypothesis can be, at least in principle, falsified. Propositions that are untestable, unfalsifiable are not worth much. Consider the grand idea that our Universe and everything in it is just an elementary particle — an electron, say — in a much bigger Cosmos. But if we can never acquire information from outside our Universe, is not the idea incapable of disproof? You must be able to check assertions out. Inveterate skeptics must be given the chance to follow your reasoning, to duplicate your experiments and see if they get the same result.

The Fine Art of Bullshit Detection drills deeper. Carl Sagan writes, “Just as important as learning these helpful tools and techniques, is unlearning and avoiding the most common pitfalls of common sense. In addition to teaching us what to do when evaluating a claim to knowledge, any good baloney detection kit must also teach us what not to do. It helps us recognize the most common and perilous fallacies of logic and rhetoric. Many good examples can be found in religion and politics, because their practitioners are so often obliged to justify two contradictory propositions”.

The Fine Art of Bullshit Detection drills deeper. Carl Sagan writes, “Just as important as learning these helpful tools and techniques, is unlearning and avoiding the most common pitfalls of common sense. In addition to teaching us what to do when evaluating a claim to knowledge, any good baloney detection kit must also teach us what not to do. It helps us recognize the most common and perilous fallacies of logic and rhetoric. Many good examples can be found in religion and politics, because their practitioners are so often obliged to justify two contradictory propositions”.

Carl Sagan goes on to admonish the most common and perilous pitfalls — many rooted in our chronic discomfort with ambiguity — and he uses examples of each in action.

1. Ad hominem — Latin for “to the man,” attacking the arguer and not the argument (e.g., The Reverend Dr. Smith is a known Biblical fundamentalist, so her objections to evolution need not be taken seriously)

2. Argument from authority (e.g., President Richard Nixon should be re-elected because he has a secret plan to end the war in Southeast Asia — but because it was secret, there was no way for the electorate to evaluate it on its merits; the argument amounted to trusting him because he was President: a mistake, as it turned out)

3. Argument from adverse consequences (e.g., A God meting out punishment and reward must exist, because if He didn’t, society would be much more lawless and dangerous — perhaps even ungovernable. Or: The defendant in a widely publicized murder trial must be found guilty; otherwise, it will be an encouragement for other men to murder their wives)

4. Appeal to ignorance — the claim that whatever has not been proved false must be true, and vice versa (e.g., There is no compelling evidence that UFOs are not visiting the Earth; therefore UFOs exist — and there is intelligent life elsewhere in the Universe. Or: There may be seventy kazillion other worlds, but not one is known to have the moral advancement of the Earth, so we’re still central to the Universe.) This impatience with ambiguity can be criticized in the phrase: absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

5. Special pleading, often to rescue a proposition in deep rhetorical trouble (e.g., How can a merciful God condemn future generations to torment because, against orders, one woman induced one man to eat an apple? Special plead: you don’t understand the subtle Doctrine of Free Will. Or: How can there be an equally godlike Father, Son, and Holy Ghost in the same Person? Special plead: You don’t understand the Divine Mystery of the Trinity. Or: How could God permit the followers of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam — each in their own way enjoined to heroic measures of loving kindness and compassion — to have perpetrated so much cruelty for so long? Special plead: You don’t understand Free Will again. And anyway, God moves in mysterious ways.)

6. Begging the question, also called assuming the answer (e.g., We must institute the death penalty to discourage violent crime. But does the violent crime rate in fact fall when the death penalty is imposed? Or: The stock market fell yesterday because of a technical adjustment and profit-taking by investors — but is there any independent evidence for the causal role of “adjustment” and profit-taking; have we learned anything at all from this purported explanation?)

7. Observational selection, also called the enumeration of favorable circumstances, or as the philosopher Francis Bacon described it, counting the hits and forgetting the misses (e.g., A state boasts of the Presidents it has produced, but is silent on its serial killers) statistics of small numbers — a close relative of observational selection (e.g., “They say 1 out of every 5 people is Chinese. How is this possible? I know hundreds of people, and none of them is Chinese. Yours truly.” Or: “I’ve thrown three sevens in a row. Tonight I can’t lose.”)

8. Misunderstanding of the nature of statistics (e.g., President Dwight Eisenhower expressing astonishment and alarm on discovering that fully half of all Americans have below average intelligence);

9. Inconsistency (e.g., Prudently plan for the worst of which a potential military adversary is capable, but thriftily ignore scientific projections on environmental dangers because they’re not “proved.” Or: Attribute the declining life expectancy in the former Soviet Union to the failures of communism many years ago, but never attribute the high infant mortality rate in the United States (now highest of the major industrial nations) to the failures of capitalism. Or: Consider it reasonable for the Universe to continue to exist forever into the future, but judge absurd the possibility that it has infinite duration into the past);

10. Non sequitur — Latin for “It doesn’t follow” (e.g., Our nation will prevail because God is great. But nearly every nation pretends this to be true; the German formulation was “Gott mit uns”). Often those falling into the non sequitur fallacy have simply failed to recognize alternative possibilities;

11. Post hoc, ergo propter hoc — Latin for “It happened after, so it was caused by” (e.g., Jaime Cardinal Sin, Archbishop of Manila: “I know of … a 26-year-old who looks 60 because she takes [contraceptive] pills.” Or: Before women got the vote, there were no nuclear weapons)

12. Meaningless question (e.g., What happens when an irresistible force meets an immovable object? But if there is such a thing as an irresistible force there can be no immovable objects, and vice versa)

13. Excluded middle, or false dichotomy — considering only the two extremes in a continuum of intermediate possibilities (e.g., “Sure, take his side; my husband’s perfect; I’m always wrong.” Or: “Either you love your country or you hate it.” Or: “If you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem”)

14. Short-term vs. long-term — a subset of the excluded middle, but so important I’ve pulled it out for special attention (e.g., We can’t afford programs to feed malnourished children and educate pre-school kids. We need to urgently deal with crime on the streets. Or: Why explore space or pursue fundamental science when we have so huge a budget deficit?);

15. Slippery slope, related to excluded middle (e.g., If we allow abortion in the first weeks of pregnancy, it will be impossible to prevent the killing of a full-term infant. Or, conversely: If the state prohibits abortion even in the ninth month, it will soon be telling us what to do with our bodies around the time of conception);

16. Confusion of correlation and causation (e.g., A survey shows that more college graduates are homosexual than those with lesser education; therefore education makes people gay. Or: Andean earthquakes are correlated with closest approaches of the planet Uranus; therefore — despite the absence of any such correlation for the nearer, more massive planet Jupiter — the latter causes the former)

17. Straw man — caricaturing a position to make it easier to attack (e.g., Scientists suppose that living things simply fell together by chance — a formulation that willfully ignores the central Darwinian insight, that Nature ratchets up by saving what works and discarding what doesn’t. Or — this is also a short-term/long-term fallacy — environmentalists care more for snail darters and spotted owls than they do for people)

18. Suppressed evidence, or half-truths (e.g., An amazingly accurate and widely quoted “prophecy” of the assassination attempt on President Reagan is shown on television; but — an important detail — was it recorded before or after the event? Or: These government abuses demand revolution, even if you can’t make an omelette without breaking some eggs. Yes, but is this likely to be a revolution in which far more people are killed than under the previous regime? What does the experience of other revolutions suggest? Are all revolutions against oppressive regimes desirable and in the interests of the people?)

19. Weasel words (e.g., The separation of powers of the U.S. Constitution specifies that the United States may not conduct a war without a declaration by Congress. On the other hand, Presidents are given control of foreign policy and the conduct of wars, which are potentially powerful tools for getting themselves re-elected. Presidents of either political party may therefore be tempted to arrange wars while waving the flag and calling the wars something else — “police actions,” “armed incursions,” “protective reaction strikes,” “pacification,” “safeguarding American interests,” and a wide variety of “operations,” such as “Operation Just Cause.” Euphemisms for war are one of a broad class of reinventions of language for political purposes. Talleyrand said, “An important art of politicians is to find new names for institutions which under old names have become odious to the public”)

Carl Sagan ends the chapter with a necessary disclaimer:

“Like all tools, the baloney (bullshit) detection kit can be misused, applied out of context, or even employed as a rote alternative to thinking. But applied judiciously, it can make all the difference in the world — not least in evaluating our own arguments before we present them to others.

“Like all tools, the baloney (bullshit) detection kit can be misused, applied out of context, or even employed as a rote alternative to thinking. But applied judiciously, it can make all the difference in the world — not least in evaluating our own arguments before we present them to others.