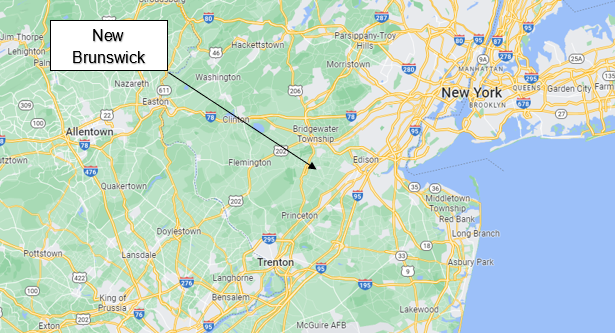

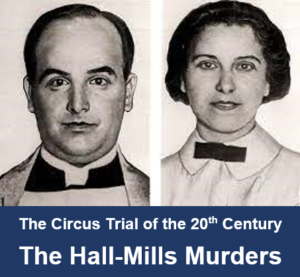

On September 14, 1922, illicit lovers Edward Wheeler Hall and Eleanor Reinhardt Mills were murdered near New Brunswick, New Jersey. Hall, age 43, was a married Episcopalian minister. Mills, age 34 and married to a different man, was a soprano in his church choir. Three people—Hall’s legal wife and her two brothers—were charged with the crimes but acquitted. One hundred years later, few alive today have heard of the Hall-Mills murder trial but, back then, it was a media circus on par with the 1990s O.J. Simpson fiasco.

On September 14, 1922, illicit lovers Edward Wheeler Hall and Eleanor Reinhardt Mills were murdered near New Brunswick, New Jersey. Hall, age 43, was a married Episcopalian minister. Mills, age 34 and married to a different man, was a soprano in his church choir. Three people—Hall’s legal wife and her two brothers—were charged with the crimes but acquitted. One hundred years later, few alive today have heard of the Hall-Mills murder trial but, back then, it was a media circus on par with the 1990s O.J. Simpson fiasco.

Normally, I write original material for the Dyingwords blog. Today, however, I’m going to plagiarize a bit because this description from The Yale Review says more about the sensational Hall-Mills side show than I can do justice to:

This steaming porridge of lust, murder, and scandal proved irresistible to the tabloids. As one eminent chronicler of the period outs it: “The Hall-Mills case had all the elements needed to satisfy an exacting public taste for the sensational. It was grisly, it was dramatic (the bodies being laid side to side as if to emphasize an unhallowed union), it involved wealth and respectability, it had just the right amount of sex interest–and in addition, it took place close to New York City, the great metropolitan nerve-center of the American press.”

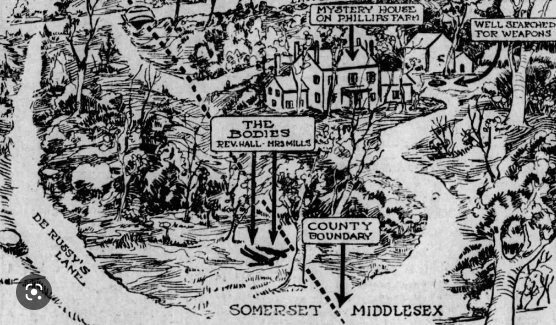

The frenzied coverage turned the old Phillips farm, where the bodies were found, into a major tourist attraction. On weekends, the crime scene became a virtual carnival with vendors hawking popcorn, peanuts, soft drinks, and balloons to the hordes of the morbidly curious who arrived “at the rate of a thousand cars a day.” Within a few weeks, the crabapple tree, under which the bodies were lying, had been completely stripped of every branch and bit of bark by ghoulish souvenir hunters, while one enterprising individual peddled samples of the dirt surrounding the now-infamous tree for twenty-five cents a bag.

Back to the story of what happened, who probably did it, and why. Let’s start with the case facts.

The Reverend Ed Wheeler was born in Brooklyn and received his theology degree in Manhattan. He moved to New Jersey in 1909 and was tenured at the Evangelist Episcopal Church in New Brunswick. Here he met Frances Noel Stevens who was eight years his senior and filthy rich, being an heir to the Johnson & Johnson fortune. They married in 1911 and had no children.

Eleanor Mills did have children. She was married to James E. Mills who was a sexton in Hall’s church and a rather n’er-do-well. Eleanor was an attractive and vivacious lady with an exceptional voice. She was a core member of the church and became Hall’s mistress.

It was no secret in New Brunswick’s society that Mills and Hall were having an affair. In fact, they were quite open about it. Many in the congregation gossiped and disapproved—not just of a clergy-parishioner relationship but the societal misalignment. Hall’s wife and family were upper class while Mills belonged with the working poor.

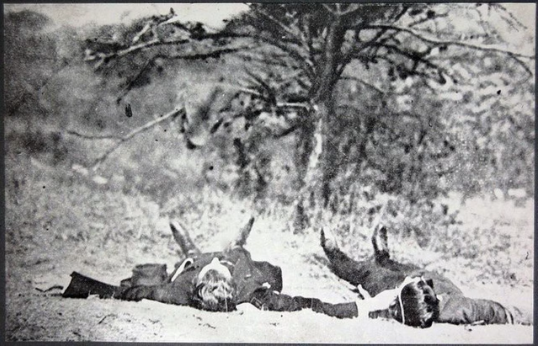

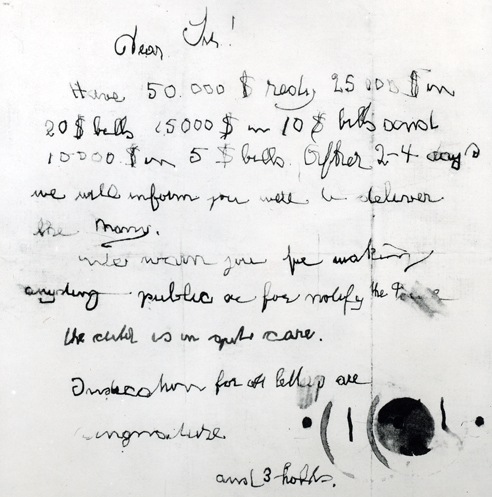

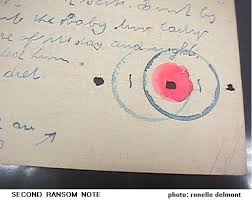

On September 16, 1922 (two days after Hall and Mills disappeared) a young couple walking through an orchard happened upon the bodies. Mills and Hall were lying side-by-side on their backs with their feet facing a crabapple tree. Hall was to Mill’s left with his arm touching hers while Mill’s arm was stretched, touching his. Hall’s Panama hat covered his face while Mills’ scarf wrapped her neck. Between the two were ripped-up love letters that Mills and Hall had previously passed back and forth. Notably, Reverend Hall’s calling card was set at his feet.

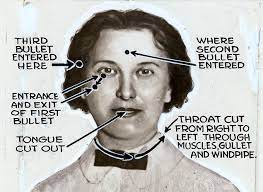

Autopsies showed both had been shot with a .32 caliber handgun. Hall received one gunshot wound to the head with the bullet entering above his right ear and travelling downward, exiting the left rear of his neck. Mills had three gunshot wounds. One was in the center of her forehead two inches above the nose. A second plowed through her right cheek. A third pierced her right temple.

There were minor bruises on Hall but couldn’t be conclusively linked to a struggle. Mills, on the other hand, had her throat slit from ear to ear, practically decapitating her. Her tongue had been extracted and was missing.

The initial investigation was How Not to Process a Crime Scene 101. The police failed to secure the area and a mass of onlookers had access not only to view the bodies but in handling evidence like the love letters and the calling card. The story quickly spread and became the frenzied craze described in the Yale Review excerpt.

From the onset, Hall’s wife—Frances Stevens Hall—was the prime suspect in setting up the murders. Not committing them, though, as that suspicion fell on her two brothers, Henry Hewgill Stevens and William “Willie” Carpender Stevens. The district attorney quickly took the case before a grand jury theorizing that Frances was the jealous mastermind while Henry and Willie were the obliging gunmen.

The grand jury didn’t buy it due to a lack of evidence. They rejected an indictment and the case went dormant for four years. In the legal system, that is.

In the news system, the Hall-Mills murder case was far from forgotten. The early 1920s was a vibrant time. Americans were recovering from a war and a pandemic. They wanted a release. The media gave it to them with the birth of American-style tabloids which rejected the stiff-collar, upper-crust reporting style of the New York Times.

William Randolph Hearst began publishing British-like papers targeting sensationalism. Hearst’s New York Daily Mirror competed with the already established tabloids New York Daily News and the New York Graphic. Hearst, being the cunning entrepreneur he was, looked to one-up the competition. He found one story that had it all—love & sex, money, and murder. Throw in a philandering clergyman and he had what Americans of the Roaring Twenties wanted to read.

The NY Daily Mirror resurrected the Hall-Mills murder case in 1925. Investigating reporters dug up “new evidence” which was so publicized that the New Jersey officials couldn’t ignore it. There were a few overlooked items from the 1922 investigation that showed up on the tabloid covers.

One was that Willie Stevens owned a .32 caliber pistol. Two was that Willie Stevens’s fingerprint was on the calling card found at the dead feet of Ed Hall. Three was the “Pig Woman” who claimed to have seen the murders go down.

This time, the New Brunswick grand jury indicted the three original suspects. The trial started on November 3, 1926 in neighboring Somerset, New Jersey. And if the original crime scene was a media gong show, that held nothing compared to the trial. At least three hundred news reporters covered the 33-day debacle.

The Pig Woman was the star prosecution witness. Now, there’s a story behind this pig lady. Her name was Jane Gibson or Jane Easton or Jane Upson, depending on what she wanted for the day. Jane got her pig woman name from being a farmer who kept hogs on the property next door to the orchard where the Hall and Hills bodies were found.

The Pig Woman never surfaced in the 1922 investigation, but she miraculously appeared when the tabloid coverage began. Jane stated that on the evening of September 14, 1922, her dog began barking and indicating toward the orchard. Being curious, Jane rode her mule over to the site and witnessed the three accused Stevens siblings there with the victims. As she was leaving, she heard gunshots, then went back to see Mrs. Frances Hall weeping over her dead husband’s body.

Now credibility is an important issue in witness testimony. It doesn’t help a jury’s impression when the witness’s mother (Jane’s own mom) kept yelling from the back of the courtroom while her daughter was testifying, “She’s a liar. A liar. A liar.” Nor does it create a reassuring picture when the star witness, who’s being called a liar, testifies from a hospital bed that had to be wheeled into the packed-to-over-capacity courtroom.

The three accused, Frances Stevens Hall, Henry Stevens, and Willie Stevens, all took the stand and testified on their own behalf. Frances, the stoic, denied any motivation, means, and opportunity. Henry’s defense was “Prove it. I have nothing to hide”. Willie was a special case. He was known as “Nutty Willie” in the community and probably had high-functioning autism. Apparently, he played the prosecutor like a hooked fish.

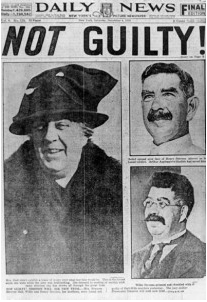

To use the cliché “in the end”, the jury acquitted Frances, Henry, and Willie. Their dream team defense counsel turned the trial into a class war where Ed Hall stooped to be with a common cheating wife like Eleanor Mills and they deserved what they got. Here’s a quote from a Rutgers pdf paper titled The Hall-Mills Murder Case: The Most Fascinating Unsolved Murder in America:

Frances Hall was presented as a paragon, along with her two brothers. “Have they been thugs?”, her lawyer asked the jury. ”Have they criminal records? Are they thieves? No. They are refined, genteel, law-abiding people, the very highest type of character, churchgoing Christians, who up to this time enjoyed the perfect admiration and respect of their friends and neighbors.”

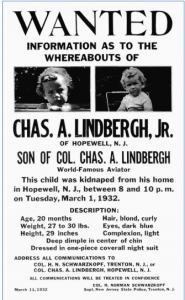

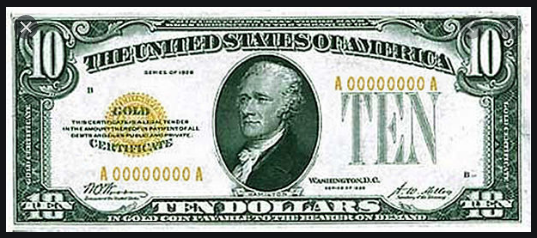

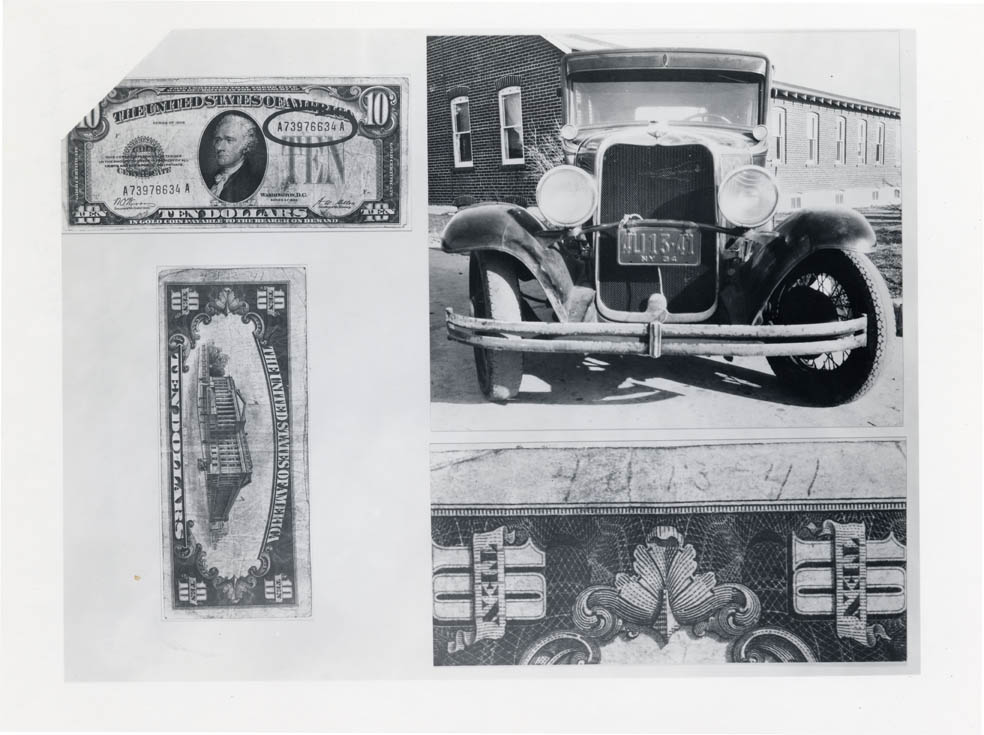

When the jury acquitted Frances, Henry, and Willie the media manic trial was over, but the tabloids milked it until another sensational case came about. In 1932, famed aviator Charles Lindbergh’s baby was abducted and murdered. The tabloids finally closed the Hall-Mills case.

When the jury acquitted Frances, Henry, and Willie the media manic trial was over, but the tabloids milked it until another sensational case came about. In 1932, famed aviator Charles Lindbergh’s baby was abducted and murdered. The tabloids finally closed the Hall-Mills case.

Over the last century, there’ve been numerous books written and articles submitted that looked at the Hall-Mills murders. There’s a guy named Julius Bolyog who came out 47 years after the murders stating he was a middle-man between the Frances and Willie connection and the hired killers. I seriously question his credibility. His account doesn’t pass the smell test, but you can listen to a 9-part recording produced in 1970 documenting Bolyog’s claim.

Then there’s the exhaustive work by Gerald Tomlinson titled Fatal Tryst: Who Killed the Minister and the Choir Singer? This author somehow concludes the Ku Klux Klan did it. Whatever.

So, what do I think? What an old murder cop thinks? Someone who’s been there, done that in murders?

The first thing to mind is the body positions. This was ritualistic. Hall and Mills were placed on their backs, touching each other, facing the crabapple tree with their torn love letters between them for a reason. These murders were all about infidelity.

I don’t think they were killed at this site. Rather, they were shot elsewhere and transported to the orchard knowing full well they’d be found, and the statement made. The killers wanted their victims publicly presented and a message sent.

I say killers (plural) because I don’t believe Hall and Mills were done at the dump site. It’d take two people to load, transport, and display the bodies. Handling a limp dead body by yourself is a tough go. Believe me. I was a coroner, and I know about the challenges in handling dead bodies.

I find the gunshot wounds telling. Ed Hall was shot from above and downward. From his upper right to his lower left. Eleanor Mills was shot three times, and it seems to me the shooter had to work on her. I’d say the first shot caught her struggling and zipped through her cheek. The second was more controlled and went through her temple. The third was a finish-off through the forehead after she was face-first controlled.

Control. This crime speaks to a planned control. The killers and plotter had to find the two—Ed Hall and Eleanor Mills—together and take control so they would initially cooperate. This might have been in a vehicle as it’s had to quickly get out of a vehicle when things go deadly fast.

I speculate the killers sucked Hall and Mills into the back seat of a car. Hall was on the rear driver’s side. Mills was on the rear passenger’s side.

By sucking in, I mean blackmailing. Somehow, the killers got Hall and Mills attention to get them controlled. Blackmailing will do that.

The gunshot patterns are telling. I speculate the shooter was in the passenger front position. The other killer was behind the wheel. The shooter first pulled the trigger on Hall which explains the downward, right-to-left trajectory.

I speculate Mills immediately turned left toward Hall when he was shot, exposing the right side of her face to the gunman. The shooter turned the pistol on her and got the first bullet through her cheek as she was moving to her left. The second shot to Mills got her in the right temple which would be a natural trajectory. The third shot was a fate-de-complete in her forehead. Probably this was post mortem in the orchard because the exhibit list records one .32 casing found at the death site.

I speculate Mills immediately turned left toward Hall when he was shot, exposing the right side of her face to the gunman. The shooter turned the pistol on her and got the first bullet through her cheek as she was moving to her left. The second shot to Mills got her in the right temple which would be a natural trajectory. The third shot was a fate-de-complete in her forehead. Probably this was post mortem in the orchard because the exhibit list records one .32 casing found at the death site.

The throat slit? I speculate this was also symbolic, but I don’t speculate this was done in the car. Too hard to do and too messy—too much blood. I’d say this was done post-mortem, in the orchard after the bodies were placed. The throat-slit and de-tonguing symbolism? Something about a message not to talk, I’d guess.

Who do I speculate were the mastermind, shooter, and wheelman?

I use two homicide investigation principles I’ve known for years. One is Occam’s razor—where when presented with two opposing hypotheses, the simplest answer is usually the correct answer. The Ku Klux Klan? Or within the family?

Two is the time-tested principle that the stranger the case, the closer the answer is to home. The Ku Klux Klan or the family?

So who, in my old murder cop opinion, planned it, carried it out, and why?

Frances Stevens Hall ordered it to send a message to New Brunswick’s society. She’d had enough of her cheating husband embarrassing her with a low-class floozie. She needed to send a strong social statement to maintain her wealth and power status.

I’d say Henry pulled the trigger while Willie was behind the wheel. It’s just a guess. But I’d say Willie, with his autistic creativity, staged the dump scene.

Then, again, who am I to speculate 100 years after the fact.