On May 6, 1937, the largest airship ever built caught fire and crashed at Lakehurst, New Jersey. The Hindenburg, or Zeppelin dirigible named after Hitler’s predecessor, Paul von Hindenburg, was completing a transatlantic flight from Frankfurt—already 12 hours late due to strong headwinds and deteriorating weather. The horror took 36 lives, destroyed the aircraft, and ended the airship industry. Over the years, there’ve been competing theories as to what happened, but little revealed about who really caused the Hindenburg airship disaster.

On May 6, 1937, the largest airship ever built caught fire and crashed at Lakehurst, New Jersey. The Hindenburg, or Zeppelin dirigible named after Hitler’s predecessor, Paul von Hindenburg, was completing a transatlantic flight from Frankfurt—already 12 hours late due to strong headwinds and deteriorating weather. The horror took 36 lives, destroyed the aircraft, and ended the airship industry. Over the years, there’ve been competing theories as to what happened, but little revealed about who really caused the Hindenburg airship disaster.

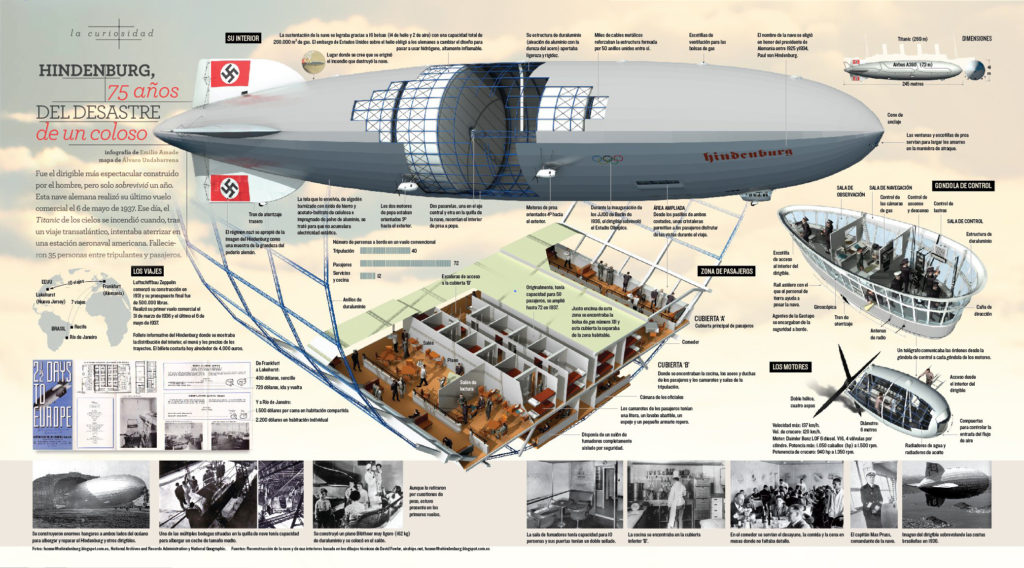

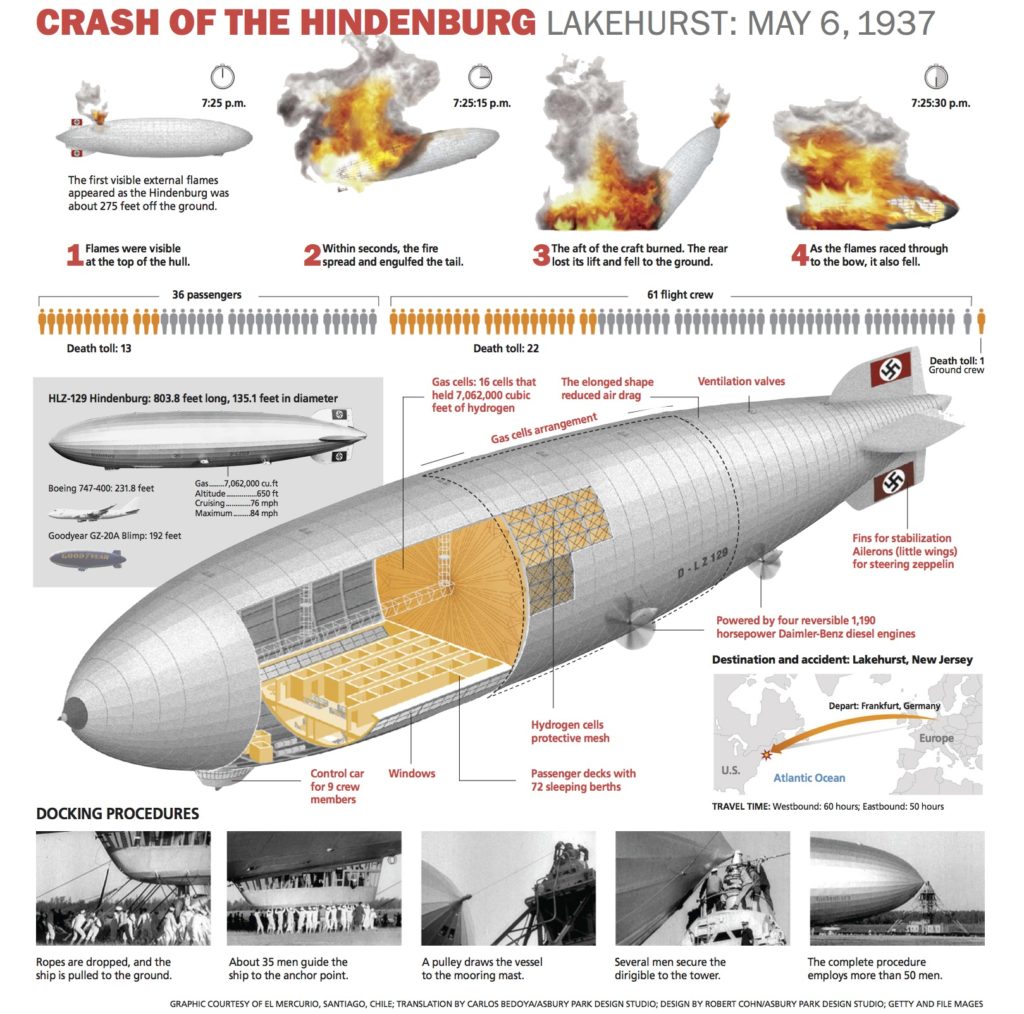

The Hindenburg was an impressive sight and a technological marvel of the time regardless that it bore Nazi swastikas on its tail. It was 804 feet long—three times the length of a Boeing 747 (79 feet shorter than the Titanic)—135 feet in center diameter and weighed 242 tons. That’s a massive amount of gravity pull for a lighter-than-air, hydrogen-filled vehicle.

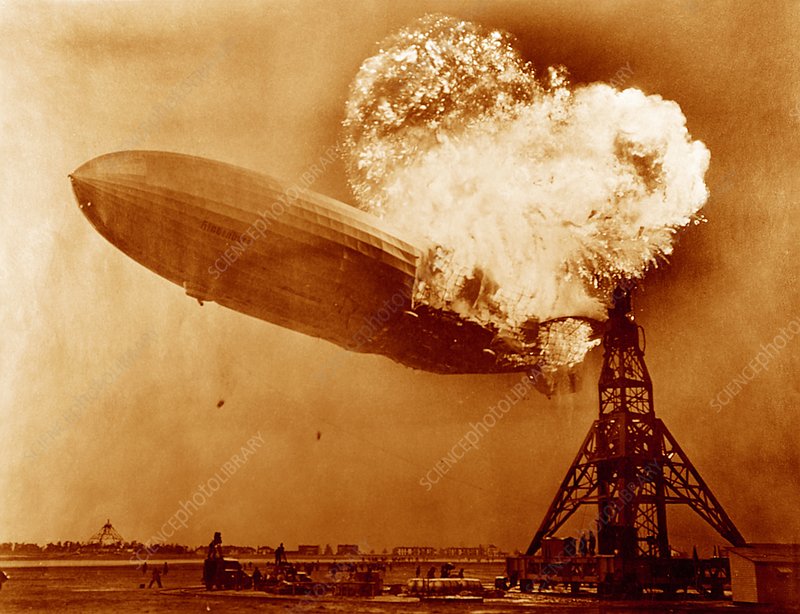

When the Hindenburg airship erupted into a flaming ball, news cameras below caught the entire conflagration. It’s been shown on newsreels across the world and, today, it’s easily viewed on Youtube. The film is black and white, grainy, and reminiscent of pre-WW2 camera technology.

Click Here to watch the original Hindenburg burn and crash newsreel

What the film doesn’t show is whose ideological ambitions and actions set a disastrous chain of events into motion. Let’s look at the history of the Hindenburg, its fatal flight details, the theories, and some chemical science before concluding who was directly or indirectly at fault in this terrible tragedy.

Germany began developing its airship program at the onset of WW1 with lighter-than-air vehicles serving as military surveillance craft. Upon the armistice that ended the Great War, the United States forced Germany to turn over their remaining dirigibles to the US Navy who housed the fleet at Naval Air Station Lakehurst. The Americans built an infrastructure to support the ships including tie-up towers so that the vessels didn’t have to directly touch land.

The Hindenburg (Luftschiff 129) was launched on May 4, 1936. It followed an earlier design called the Graf Zeppelin which debuted in 1928. By the time the Hindenburg was destroyed, the Graf had made 590 transatlantic trips covering a million miles and carrying 34,000 passengers without a safety incident. The Hindenburg had 34 accident-free trips in the year it was in operation.

Hindenburg was a next-generation airship. It was powered by four 1200 horsepower Daimler-Benz reversible diesel engines that rotated quad-bladed propellors. Without wind current effects, the Hindenburg cruised at 76 miles per hour which was over twice the speed of the fastest ocean liner. This was attractive to the time-conscious 1-percenters who could afford a ticket from Germany to America. Back then, the fare was $450 USD. Today the ride would cost $7600.

Construction details of the Hindenburg included a webbed steel frame covered by a cotton-based fabric treated with advanced (for the time) treatments. It had sixteen independent and sealed bladders to house the inflation gas which were made of gelatinized latex rubber. The flight control module was in the lower bow area, ahead of double decks for the passengers and crew quarters.

The Hindenburg rivaled the Titanic when it came to luxurious travel. Paying guests could experience fine food and wines as well as relax in a sealed smoking room. Because of the extreme fire danger onboard a gas-floated airship, passengers were removed of all spark and fire-triggering devices like cigarette lighters and matches.

The dangerous gas on the Hindenburg was 7,600,000 cubic feet of pure hydrogen. The ship, like other German dirigibles, was designed to use helium gas which was inert, not like extremely flammable hydrogen. There was a reason why Germany used hydrogen instead of helium.

The United States had passed a law called the Helium Control Act of 1927. Initially, this was to conserve helium reserves, but it was also to control a world monopoly on helium and discourage other nations from expanding their military versions of floating airships. As the Hitler-led Nazis became more and more of an obvious threat in the mid-1930s, the Americans became even more strict in supplying Germany with any gas for their air fleet—military or civilian. With Hitler in power, there was no way the Nazis could purchase helium, so with hydrogen being cheap and easy to produce (unlike helium) the Nazi-backed industry went ahead and used hydrogen.

“But hydrogen is so dangerous,” you say. “Why on earth would they put it in an airplane?” Here’s a quote from a resource article I sourced:

The German attitude about hydrogen in airships was the same as our current attitude about gasoline in our cars. When you go to work, you’ve got 10 to 12 gallons of gasoline in your fuel tank which is far more explosive and dangerous than hydrogen. You don’t think anything about that because everything is operating as it is supposed to be.

The Hindenburg departed Frankfurt at 7:16 pm local time on May 3, 1937. Pilot Max Pruss and First Officer Ernst Lehmann were part of the 39-person crew who attended to 38 passengers. The ship took its regular route flying 650 feet over the Netherlands and then out over the Atlantic to meet the North American coast at Boston, continuing southward past New York City and docking at Lakehurst.

Because of unusually strong headwinds, the Hindenburg was a half-day late arriving. There was another docking delay—a significant thunder and lightning storm. Safety protocols for the hydrogen-loaded prohibited every craft from grounding during a lightning storm. It wasn’t the risk of the craft being directly struck by lightning while in flight. Many were and they were designed to take direct electrical hits as long as there was no grounding path for voltage transfer.

To understand what physically led to the Hindenburg’s destruction, it’s best to follow an extremely well-recorded timeline of events on the afternoon and evening of May 6, 1937.

4:15 — Hindenburg arrives at the mooring dock area. The electrical storm is ongoing, and the ground control directs the craft to loiter and wait out the storm.

6:22 — Ground control observes a weather break but expects conditions to worsen. They give the Hindenburg an order to make “the earliest possible landing”.

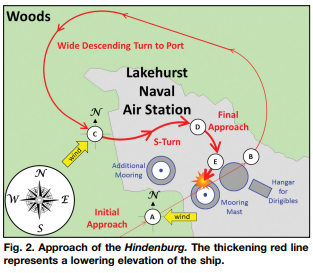

7:08 — Hindenburg returns to the mooring dock. It encounters strong easterly winds and bypasses the dock tower, making a wide circle past the dock and to the port or left side of the craft.

7:16 — Hindenburg reapproaches the dock but encounters a strong gust from the southwest. The pilot compensates by putting the craft in a tight and hard S-turn.

7:18 — Something serious happened. The ship’s stern begins to drop, and the crew immediately drops 300 kg of ballast water to adjust the buoyancy.

7:19 — The stern continues to drop. Two more ballast discharges of 300 and 500 kg are made. The pilot also orders six crew members to run to the bow to balance the weight.

7:21 — The Hindenburg was above the docking pad at 300 feet in elevation. The wet manila tethering ropes were cast from the ship and hit the pad, effectively electrically grounding the steel airframe.

7:25 — The ground crew begins winching the Hindenburg down to the docking portal. The fabric on top of the craft, right where the tail rises, begins to ripple and a yellow flame appears.

7:25:05 — The entire tail section erupts in an orange flame ball. The stern rapidly sinks.

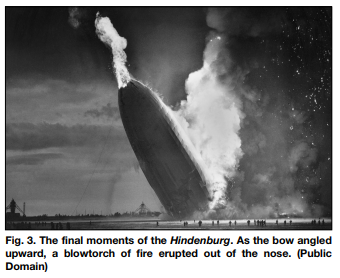

7:25:10 — Now the rear half of the ship is engulfed in fire, and the tail is near the ground with the bow violently raised.

7:25:20 — The bow ejects a “flamethrower’ burst or flame jet from the nose.

7:25:34 — The Hindenburg is on the ground, completely consumed in flames.

In the aftermath, the yellow-orange fire rapidly burns itself out, but the black smoke from the diesel fuel supply goes on for two hours. 35 people are dead at the scene including 13 passengers, 22 crewmen, and one ground worker caught underneath the ship. Over the next few days, several others died from their burn injuries.

The Hindenburg disaster effectively ended the floating airship industry. The public confidence was gone, and Germany suffered a black eye in the face of what was soon to be another world war. Besides, the airship model was already obsolete as heavier-then-air craft were already making transatlantic and transpacific flights safely and much more cost-effectively, not to mention the speed of modern airplanes.

This brings us to look at the theories as to what and who caused the Hindenburg disaster. This was an extremely high-profile world event. Naturally, conspiracy theories would show up. We’ll dismiss a few of the far-out suggestions before drilling down into the chemical science of how the Hindenburg was built and what really went wrong to cause such a catastrophic aircraft failure.

Sabotage — This theory holds no merit. There has never been any evidence to support the theory that someone intentionally scuttled the ship. However, the sabotage theory did come up in the official inquiry and it was raised by Captain Pruss as well as the naval base commander, Charles Rosenthal.

Lightning Strike — The weather at the naval base was continually recorded while the Hindenburg was docking and there was no electrical activity at the time. This is why they were making the dock. Hydrogen dirigibles were prohibited from making ground contact if lightning was present.

Engine Failure and Sparks — Again, there is zero evidence of this. The engines were in perfect working order. Besides, the sparks from a diesel engine’s exhaust would only reach 250C whereas hydrogen ignites at 500C.

Pilot Error/Crew Negligence — No real evidence of this either. At least, nothing intentional or supremely careless. This also applies to a hydrogen valve failing or being accidentally opened during the water balast discharges.

Catastrophic Mechanical Failure Causing a Chain Reaction in a Flammable Environment — This is the most likely scenario, and it takes some explaining. It’s necessary to look at the systems and structure of the Hindenburg to make some sense of the leading theory that has been discussed for years and analyzed by leading scientists and experts in the aeronautic industry.

The Hindenburg, like all dirigibles, was built with four interconnected systems. One was the airframe, skin, and stabilizers. Second was the flotation system with the hydrogen tanks. Third was the propulsion system. And fourth was the control system.

The airframe was a rib-work of honeycombed steel framing. There was nothing flammable about the steel and the grade was sufficiently high. It’s highly unlikely that the Hindenburg suffered any damage to the main frame which might have accidentally been broken. The same can’t be said of the stabilizers and supports.

The skin on the Hindenburg was extremely flammable. It was a cotton-based fabric that was treated with chemical compounds in a method called doping. This was common in the 1920s and 30s as many fixed-wing airplanes had fabric skins rather than metal. It was all about weight control.

In Hindenburg disaster terms, this is called the incendiary paint theory. It was developed in 1997 by Addison Bain who was a NASA engineer. Yes, a rocket scientist. He analyzed remnants of the Hindenburg skin that survived the crash and found the doping components were a mixture of Iron II Oxide (FeO3), Aluminum (AI), and Cellulose Acetate Butyrate (CAB). Mixing CAB and AI with Iron Oxide is a recipe for an incendiary bomb that goes off with what’s known as a chemical or pyrotechnical thermite reaction. It requires high heat to activate the thermite reaction, but having a hydrogen fire under the doped skin would do it.

The Hindenburg’s flotation system was a series of sixteen sealed rubber tanks with control valves for filling and releasing hydrogen. Hydrogen is perfectly stable and safe provided it’s contained outside of oxygen and away from an ignition source. The total hydrogen volume in the tanks was 7,600,000 or 475,000 ft3 per tank. By anyone’s standards, that’s a lot of fuel to burn.

There is no indication that the Hindenberg’s propulsion system failed. The Germans were, and still are, well-known for building dependable diesel engines and drive components. At the ignition, fire, and crash time, the four engines were operating normally. Also, the diesel fuel storage containers were not leaking and could not have contributed to the disaster. Note that the diesel fuel ignited after the main fire as evidenced by the following black smoke.

The control system also had no red flags. If there was a problem with controlling the Hindenburg, the crew would have known it. The Captain and First Officer survived to testify at the official inquiry and would have said something. The only unusual matter they reported was the stern suddenly sagging during the last seven minutes.

In an accident investigation process called case mapping, or root cause analysis, the method is to identify the outcome and then identify the events that caused it to occur. Let’s start with the outcome–the Hindenburg was destroyed, killing 38 people, wounding many others, and ending the airship industry. Why did this happen? Because the Hindenburg caught fire and crashed.

What caused the fire? Well, let’s stop for a bit and examine the first sign of trouble. That was the sagging stern. Why did the stern begin to sag? Because it was losing buoyancy. Likely, this was because buoyant hydrogen gas was leaking from a compromised bladder in the rear section.

What caused the bladder to be compromised and leak? It’s safe to rule out an intentional venting or discharge caused by the crew. It’s also safe to eliminate a faulty valve or the crew’s instruments would have detected the default. It’s far more likely that the bladder was damaged and punctured.

What could have ruptured the bladder? The first clue is this occurred in the furthest bladder to the rear. This is where the mechanical arms are for the rudder and stabilizer. The theory goes that one or more of the mechanical arms snapped and ripped open the bladder.

What could have caused an arm to snap? Let’s look at the event occurring two minutes before the sag started. At 7:16, the pilot executed the sharp S-turn to deal with a sudden wind gust. Up till then, everything was routine. It’s thought excess stress from the turn caused a rudder or stabilizer support arm to snap and rip right through the rubber bladder causing hydrogen to leak out and rise, filling the space above it—just under the skin.

Note that at 7:25, ground witnesses saw the skin begin to rumple at the base of the tail and a yellow flame appear. Five seconds later, the entire tail section was in an orange flame ball. From there, the fire progressively and quickly spread from the back to the front.

Hindenburg disaster, coloured image. View of the German airship Hindenburg (LZ 129) on fire over Naval Air Station (NAS) Lakehurst, New Jersey, USA, on 6th May 1937. This airship is famous for the Hindenburg disaster of 6th May 1937, when it caught fire and was destroyed during its attempt to dock with its mooring mast at NAS Lakehurst. Of the 97 crew and passengers on board 35 were killed, along with one member of the ground crew. The balloon was filled with hydrogen, a highly flammable gas. The cause of the accident has never been established but the disaster destroyed public confidence and marked the abrupt end of the airship era. Here the ships water ballast tanks (black dots, lower centre-left) can be seen falling.

Why was this happening? Logic says that the heat from the hydrogen-fueled and incendiary skin coating melted the other bladders and released more hydrogen at an enormous rate. The skin, being extremely flammable when heated to the thermite point, was consumed in under one minute.

It’s worthy to note the flame colors. Hydrogen, when pure and on fire, burns with a faint blue hue. The coloration is towards the ultraviolet scale and would be more noticeable in the dark than the light. The burning doped skin, however, has a different color scale and would present in the yellow-orange range which was reported by all witnesses. Diesel, being diesel, burns black.

So, it’s all well that we’ve identified the leak and the general cause of the fire. What we haven’t ascertained is what the ignition source was. We know what it wasn’t and that’s the engine sparks, and we’re certain the Hindenburg wasn’t struck by lightning. So where did the ignition source come from?

This is where the static electricity theory comes in. The thunder and lightning meteorological conditions in coastal New Jersey that evening were perfect for creating a static electricity buildup within a metal and fabric creation like the Hindenburg. Containing static electricity is safe when a structure is already grounded or remains afloat and ungrounded. However, the grounding act allows an instant electron flow from positive to negative or from the high source to the low source.

It’s likely when the aircrew lowered the wet manila tethering ropes at 7:21, the ground connection was made and the static buildup in the Hindenburg was released. It’s thought that within the metal airframe there was the right-sized gap between two metal components to create an electron jump known as a brush discharge which allowed a spark to ignite the runaway hydrogen gas that was mixing with oxygen. The ideal spot would have been between a broken metal support component and the steel frame, right above the furthest rear bladder that was ruptured and spewing flammable gas into the oxygen-filled space under the skin.

To me, who is trained by Think Reliability as an accident investigator using the cause mapping technique, this perfect storm of a dirigible built of incendiary skin over a steel frame encased leaked hydrogen into an oxygen-rich container and ignited by a spark started by a static electricity buildup arced through a gap between a broken member and its frame makes sense.

I’m satisfied this scenario is what caused the Hindenburg to burn and crash. Taking this a step further, who is to blame for all this? A natural cause mapping progression is to ask what piece of the puzzle could be removed or changed so this tragedy would never have happened. That’s eliminating hydrogen and replacing it with helium like the Zeppelins were originally designed for.

The bottom line? Germany, because it was an extremely dangerous, world menace under Hitler’s Nazi rule, could not obtain helium from the monopolistic Americans. The Germans went ahead and used hydrogen in a government-approved aerospace program. You could make an argument that Adolf Hitler, being responsible for the Nazi government, really caused the Hindenburg airship disaster.

Hi, Garry, I really enjoyed the Hindenburg story, as the last time I heard about it was in high school about 50 years ago, and they postulated that it was a lightning strike that caused it. Your story makes the whole thing much more understandable and scientific approach to what really happened. Keep up the good work!

Thanks, William. I really appreciate the encouraging feedback. I’m confident the scenario I laid out was what happened. A lightning strike alone doesn’t seem to make sense. There had to be hydrogen gas already mixing with oxygen and something had to cause the leak. I’m sure it was a stressed frame member caused by the S-turn that created a bridge for a static electricity arc to ignite the mixture. We’ll never know for sure but I don’t think this explanation can be debunked.

Really fascinating Garry, and the diagrams are quite helpful. Great post 🙂

Thanks, June. I really knew nothing about the Hindenburg story until I stumbled upon an old Readers Digest article that detailed the “perfect storm”. Then I found a bunch of technical studies online that dove into the science aspect. So I guess what I do in this blog is find stories I’m interested in and write posts so I can make sense of them and hope others will enjoy them, too, Thanks for all your support!

Wow, Garry. Seems like a lot of things aligned that created the perfect storm. The fabric skin blew my mind. I had no idea they used fabric instead of metal back then.

Your post reminds me of the sub disaster in the news. Just heard last night, the creators of this submersible forwent safety testing. Those poor families… It’s disheartening to watch greed continue to rise above common sense and humanity.

Yeah, the sub story is terrible, Sue. Sounds like it instantly imploded so the victims probably never knew what happened. Can you imagine the other scenario where it lay incapacitated on the bottom and the occupants could only wait until their air ran out. BTW, I had no idea the Hindenburg was silver in color – that must be from the aluminum in the doping treatment. Seeing a colorized version was a surprise and those swastikas on the tail… creepy!