The Amanda Knox story captured worldwide attention during the years she passed through the Italian legal system and was convicted—twice—of complicity in murdering her college roommate, Meredith Kercher. Ultimately, Knox was exonerated of the murder charges but convicted of criminal slander based on coerced statements she made while under initial and unlawful police interrogation. Now, the international spotlight is again upon Knox with a retrial underway after her slander charge was overthrown by Italy’s highest court. All this circles back to many still questioning if Amanda Knox really is innocent of murdering Meredith Kercher.

The Amanda Knox story captured worldwide attention during the years she passed through the Italian legal system and was convicted—twice—of complicity in murdering her college roommate, Meredith Kercher. Ultimately, Knox was exonerated of the murder charges but convicted of criminal slander based on coerced statements she made while under initial and unlawful police interrogation. Now, the international spotlight is again upon Knox with a retrial underway after her slander charge was overthrown by Italy’s highest court. All this circles back to many still questioning if Amanda Knox really is innocent of murdering Meredith Kercher.

There’s a lot of internet information on the Amanda Knox murder case. Some of it’s factual. Much is sensational tabloid junk about “Foxy Knoxy”—the “Ice Lady”—disseminated by socially dysfunctional trolls operating from surplus metal sea-cans converted into dwellings via an extension cord hooked to one bare light bulb. To find out the truth, it’s necessary to first look at the overall facts and then examine how the Italian legal system handled the case through a dragged-out, eight-year-long process.

In 2007, Amanda Knox was a 20-year-old student from Seattle, Washington. She moved to Perugia in central Italy (slightly north of Rome) to further her journalism studies as Perugia was well-known for outstanding universities and educational opportunities—a popular place for foreign students. Here, Knox met a British exchange student, 21-year-old Meredith Kercher, and they shared a ground-floor, four-bedroom apartment with two other young ladies.

Quickly, Knox became romantically involved with a young Italian man, Raffaele Sollecito, and Kercher did the same with Giacomo Silenzi. At the time, Knox also worked part-time in a nightclub run by Patrick Lumumba. It was this pentagon of five that the Italian prosecutors would present as a sex game gone wrong that resulted in Meredith Kercher’s death.

On the evening of November 1, 2007, Knox, Sollecito, Silenzi, and Kercher socialized with others at Sollecito’s apartment near to where the ladies roomed. Present was a man named Rudy Guede who was invited by one of the group members but who was unknown to Knox and Kercher. Around 9 pm, Kercher excused herself from the gathering and walked back to her residence alone. Bit by bit, the gathering broke up leaving Knox and Sollecito to overnight there together.

At midday on November 2, Knox repeatedly tried to phone Meredith Kercher. She got no answer and became concerned, so Knox and Sollecito went to the co-habitation and found Kercher’s bedroom door locked. Knox tapped on the door and called out, but Kercher didn’t answer. Then Knox and Sollecito noticed some bloodstains, including a bloody footprint, in the bathroom.

Being alarmed, Knox called her mother in America who directed Knox to call the Italian police. She did so. However, there was a significant delay which was advanced as part of the prosecution’s later case against Knox and was supported by a timeline presented through cell phone records.

The first attending police officers were not homicide detectives. They were an Italian version of postal inspectors crossed with communication fraud investigators. There hadn’t been a murder in Perugia in over twenty years, so it was a considerable time before “competent” scene processors and trained murder cops arrived. Naturally, the scene was contaminated, and the ensuing DNA evidence used in convicting Amanda Knox of murdering Meredith Kercher was compromised.

What the scene processing showed was Kercher had been attacked, raped, and had her throat cut in her bedroom. Her official cause of death was exsanguination (bleeding out) after being injured with a sharp-edged weapon. Kercher’s bedroom window was open, and the investigators deduced that to mean that a break-in had been staged with the real killer setting the crime up to appear that a stranger was involved.

Police initially treated Amanda Knox as a witness. She was questioned on different occasions, but the homicide investigators slowly formulated a theory that Knox was lying to protect the actual murderer. They also developed a motive theory that Kercher was killed because she refused to take part in a multi-person sexual trist. An orgy.

On November 6, the Italian homicide detectives again brought Knox in for questioning. This time it turned into a full-on, hard-core interrogation that lasted hours. This is a complex and controversial part of the Amanda Knox story and precise details—at least as precise as possible because the authorities did not audio or video record it (rather they elicited a written confession from Knox)—can be read on the website amandaknoxcase.com under The Interrogation of Amanda Knox.

In Amanda Knox’s written confession, she states to have been present while her nightclub boss, Patrick Lumbumba, raped and murdered Meredith Kercher. Knox did not supply any motive or any details which only an involved person would know. Lumbuba was arrested on the strength of Knox’s statement and it was shortly proven, beyond all doubt, that Lumbumba had an air-tight alibi and he was flat-out innocent. (This “accusation’ against Lumbumba is what led to her criminal slander conviction which is once again, in 2024, before the Italian courts. A verdict in set for June 5th.)

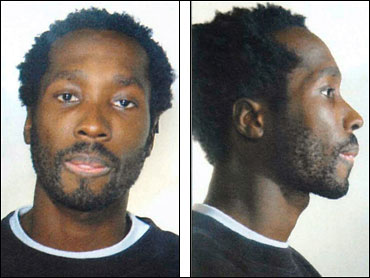

Amanda Knox was held in custody while the prosecution put an indictable case together. Meanwhile, the scene forensic evidence identified a DNA profile from semen on Kercher’s body. They conclusively linked it to Rudy Guede who had been at the social gathering on the evening when Kercher was last seen alive. Guede was arrested in Germany where he confessed and indicated that Amanda Knox had nothing to do with Kercher’s murder.

By now, the Italian legal system had a freight train rolling along the justice track. Instead of applying the brakes, the police, prosecutors, and judges threw more coal on the fire and kept on persecuting Amanda Knox. This was due to the archaic inquisitional system Italy was trying to gentrify into a western adversarial legal framework.

The common US-style evidence rules didn’t apply in the Italian arena. Despite Amanda Knox being hardline interrogated for hours without legal representation, being informed of her rights, denied food, water, and toilet facilities, slapped around, and breaking down in the middle of the night, the Italian court accepted Knox’s coerced confession as solid evidence that had to be admitted under their law structure. It didn’t matter that the prosecution’s perceived motive—some kinky sex game—had no factual basis, and it didn’t matter that Knox’s boyfriend, Raffaele Sollecito, provided Knox with her air-tight alibi. No, the Italian legal machine went right on persecuting Amanda Knox.

Knox stood trial through the summer and fall of 2009. Her case received massive public attention and the British tabloids sensationalized it like nothing ever seen. This was now the day of the emerging internet where chatrooms and social media made a spectacle of the trial and a massive mess of Amanda Knox’s life.

Amanda Knox was convicted of Meredith Kercher’s murder on December 4, 2009. She was sentenced to 26 years in jail. She appealed and had her murder conviction overturned on October 3, 2011, now having served nearly two years in an Italian prison.

In March of 2013, Italy’s Court of Cassation ordered a new trial and on January 30, 2014, she was once again convicted for killing Meredith Kercher. By now, Amanda Knox was back in America and was not returned to Italy during her new appeal. On March 27, 2015, Italy’s highest court again overturned her conviction, and her legal persecution was over.

Any rational person asks, “How could this miscarriage of justice possibly happen?” The answer is as complicated as the Amanda Knox story, if that’s possible to fully tell. It’s a murky mix of systematic incompetence and utter lack of regard for the truth. In the high court’s final ruling, the judge cited “sensational failures”, “glaring errors”, “investigative amnesia”, “guilty and culpable omissions”, “ignorance of expert forensic testimony that demonstrated contamination of evidence”, “outright falsification of forensic evidence”, and “a case without any foundation”.

The horrific Amanda Knox wrongful conviction story is best told by Amanda, herself. In a past interview with The Atlantic titled Who Owns Amanda Knox? , Amanda says:

Does my name belong to me? Does my face? What about my life? My story? Why is my name used to refer to events I had no hand in? I return to these questions again and again because others continue to profit off my identity, and my trauma, without my consent. Most recently, there is the film Stillwater, directed by Tom McCarthy and starring Matt Damon and Abigail Breslin, which was, in McCarthy’s words, “directly inspired by the Amanda Knox saga.” How did we get here?

In the fall of 2007, a British student named Meredith Kercher was studying abroad in Perugia, Italy. She moved into a little cottage with three roommates—two Italian law interns, and an American girl. Less than two months into her stay, a young man named Rudy Guede, an immigrant from the Ivory Coast, broke into the apartment and found Meredith alone. Guede had a history of breaking and entering. A week prior, he had been arrested in Milan while burglarizing a nursery school, and was found carrying a 16-inch knife. He was released.

A week later, he raped Meredith and stabbed her in the throat, killing her. In the process, he left his DNA in Meredith’s body and throughout the crime scene. He left his fingerprints and footprints in her blood. He fled to Germany immediately afterward, and later admitted to being at the scene.

I am the American girl in that story, and if the Italian authorities had been more competent, I would have been nothing more than a footnote in a tragic story. But as in many wrongful convictions, the authorities formed a theory before the forensic evidence came in, and when that evidence indicated a sole perpetrator, Guede, ego and reputation led them to contort their theory to maintain that I was still somehow involved. Guede was quietly convicted for participating in the murder in a separate fast-track trial, and then I became the main event for eight long years.

While I was on trial for the murder of Meredith Kercher, from 2007 to 2015, the prosecution and the media crafted a story, and a doppelgänger version of me, onto which people could affix all their uncertainties, fears, and moral judgments. People liked that story: the psychotic man-eater, the dirty ice queen, Foxy Knoxy. A jury convicted my doppelgänger and sentenced her to 26 years in prison.

But the guards couldn’t handcuff that invented person. They couldn’t escort that fiction into a cell. That was me, the real me, who returned to that windowless prison van, to those high cement walls topped with barbed wire, to those cold, echoing hallways and barred windows, to that all-consuming loneliness.

Ten years ago, at the age of 24, I was acquitted, and I tumbled into a kind of purgatory. I left one cell and immediately entered another: the quiet of my childhood bedroom. Outside, the telephoto lenses were fixed on my closed blinds. Prison had given me an appreciation for all the freedoms I’d taken for granted. Freedom showed me how many I still lacked.

As I walked back into the free world, I knew that my doppelgänger was there alongside me. I knew that everyone I would ever meet from then on would have already met, and judged, her. I had been acquitted in a court of law, but sentenced to life by the court of public opinion as, if not a killer, then at least a slut, or a nutcase, or a tabloid celebrity. Why doesn’t she just go away already? Her 15 minutes are over.

In freedom, I had become a pariah. Looking for work, going back to school, buying tampons at the pharmacy, everywhere I went I met people who already thought they knew who I was, what I’d done or not done, and what I deserved. I was threatened with abduction and torture in broad daylight; I was threatened with having Meredith’s name carved into my body. Strangers sent me lingerie and bizarre love letters.

All over the world, people believed they knew me, a warped assumption that turned me into a monster to some and a saint to others. I felt like I was always standing behind that cardboard cutout, Foxy Knoxy, saying, Hey, back here, the real me! Even most of the strangers who offered kindness and support didn’t truly see me. They loved her.

It’s hard to make friends, to date, to be a regular person when everyone you meet has a preconceived notion of who you really are, whether positive or negative. I could have chosen to hide out, to change my name, to dye my hair, and hope no one recognized me ever again. Instead, I decided to embrace the world that had dehumanized me, and all those who turned me into a product.

From the moment I was arrested, my name and face and trauma became a source of profit for news organizations, filmmakers, and other artists, scrupulous and unscrupulous. The most intimate details of my life, from my sexual history to my thoughts of death and suicide in prison, were taken from my private diary and leaked to journalists. Those journalists turned my darkest fears into fodder for hundreds of articles, thousands of blog posts, and millions of hot takes.

People speculated about my mental state and sexuality, they diagnosed me from afar, they used my predicament as a metaphor, they made TV movies about me, based characters in legal shows on me, and the worst of them took every opportunity they could, while I was in prison and while I’ve been out, to shame me for something I didn’t do, to shame me for living while Meredith is dead, to shame me for being in the very headlines they write, for being in the photographs they take without my consent.

The hypocrisy and the cruelty are maddening. And yet, being under that microscope has given me insight into how wrong a media narrative can be, how easy it is for all of us to consume other people’s lives as if they were mere content to fill up our Twitter feeds.

This focus on me led many to complain that Meredith Kercher had been forgotten. But whom did they blame for that? Not the Italian authorities. Not the press. Somehow it was my fault that the police and media focused on me at Meredith’s expense. The result of this is that 14 years later, my name is the name associated with this tragic series of events I had no control over.

Meredith’s name is often left out, as is Rudy Guede’s. When he was released from prison in late 2020, the New York Post headline read: “Man Who Killed Amanda Knox’s Roommate Freed on Community Service.” My name is the only name that shouldn’t be in that headline.

I never asked to become a public person. The Italian authorities and global media made that choice for me. And when I was acquitted and freed, the media and the public wouldn’t allow me to become a private citizen again.

I have not been allowed to return to the relative anonymity I had before Perugia. I have no choice but to accept the fact that I live in a world where my life, and my reputation, are freely available for distortion by a voracious content mill.

———

There is no doubt—no doubt whatsoever—that Amanda Knox really is innocent of murdering Meredith Kercher. She’s a true victim. A victim of a horrific crime. A victim of an abominable justice system. A victim of disgusting tabloids. And a victim of soulless trolls.

Footnote: Today, Amanda Knox is 36 years old and a mother of two. She hosts a successful podcast titled Labyrinths: Getting Lost with Amanda Knox with the themes of injustice and wrongful conviction. Amanda is a professional journalist, author, and activist. She recently signed with Hulu for a 12-part series based on her life story. One of the film’s co-producers is Monica Lewinsky.