On November 24, 1971, a mysterious man using the alias D.B. (Dan) Cooper boarded a Northwest Orient Airlines Boeing 727 flight from Portland, Oregon to Seattle, Washington. Once airborne, he produced what appeared to be a bomb in a briefcase and demanded $200,000 in ransom along with four parachutes. Once his threat was met, he donned a chute and bailed out in the dark, damp and cold. Nearly fifty years later, the infamous D. B. Cooper has never been found or conclusively identified.

On November 24, 1971, a mysterious man using the alias D.B. (Dan) Cooper boarded a Northwest Orient Airlines Boeing 727 flight from Portland, Oregon to Seattle, Washington. Once airborne, he produced what appeared to be a bomb in a briefcase and demanded $200,000 in ransom along with four parachutes. Once his threat was met, he donned a chute and bailed out in the dark, damp and cold. Nearly fifty years later, the infamous D. B. Cooper has never been found or conclusively identified.

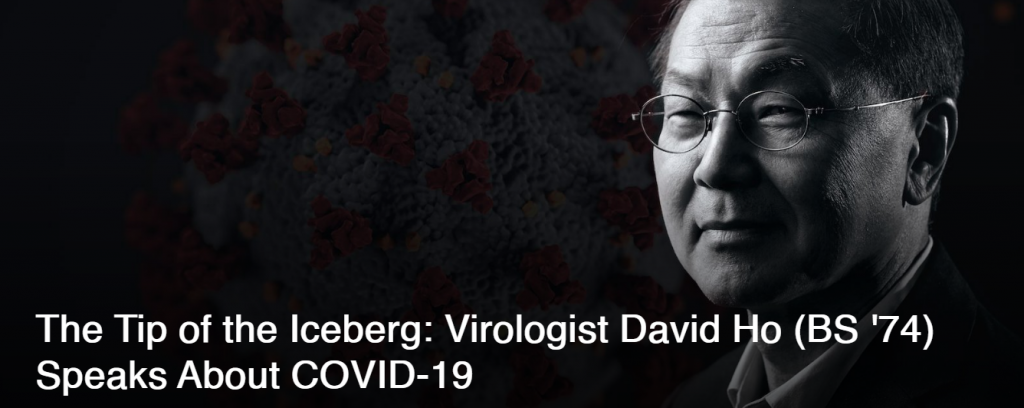

Who skyjacker D. B. Cooper really was is one of the world’s great unsolved crimes. The FBI put countless hours into following thousands of leads. By July 2016, they ran out of steam and officially closed the case. That’s not without some interesting suspects surfacing which can’t quite be ruled out. However, with advanced forensic techniques, there is still the strong possibility of solving the case—even if the real D.B. Cooper is no longer alive.

This bizarre story began on a Wednesday afternoon in Portland, Oregon. A nondescript man dressed in business attire arrived at the Northwest Orient wicket and paid cash for a one-way ticket to Seattle. He registered as Dan Cooper and boarded Flight 305 which departed at 2:50 pm for the 30-minute hop north to Seattle. On the flight were 37 passengers, including Cooper, and 4 flight staff.

This bizarre story began on a Wednesday afternoon in Portland, Oregon. A nondescript man dressed in business attire arrived at the Northwest Orient wicket and paid cash for a one-way ticket to Seattle. He registered as Dan Cooper and boarded Flight 305 which departed at 2:50 pm for the 30-minute hop north to Seattle. On the flight were 37 passengers, including Cooper, and 4 flight staff.

From witness accounts, there was nothing unusual or nervous about Dan Cooper. He ordered a bourbon and soda while taxing out and lit up a smoke. Once in the sky, Cooper called a flight attendant and passed her a hand-printed note. Cooper said, “Miss, you’d better look at that note. I have a bomb.”

Cooper’s note was specific. It read that he wanted $200,000 in “negotiable American currency” along with four parachutes—two main packs and two reserve units. He then demanded the flight land at Seattle, pick up the money, refuel and fly him on to Mexico City.

Cooper then cracked open his briefcase. The attendant saw red cylinders that looked like dynamite along with a maze of wires and switches. Cooper closed his case and directed her to alert the cabin crew. The pilot and co-pilot transmitted this information to the Seattle tower who immediately involved the police and the FBI.

Cooper then cracked open his briefcase. The attendant saw red cylinders that looked like dynamite along with a maze of wires and switches. Cooper closed his case and directed her to alert the cabin crew. The pilot and co-pilot transmitted this information to the Seattle tower who immediately involved the police and the FBI.

Flight 305 went into a holding pattern outside Seattle while Northwest Orient management approved paying the ransom. In less than two hours, they sourced 10,000 20-dollar bills and delivered the money to the Sea-Tac airport. The authorities also obtained parachutes from a skydiving club and grouped them with the ransom cash.

Once Cooper was assured his demands were being met, he instructed the airplane to land and allowed the passengers to disembark. Cooper stipulated that the pilots and one attendant stay onboard. The plane refueled and departed at 7:40 pm with a destination of Mexico City by way of another refueling stop at Reno, Nevada.

Cooper stayed in the passenger compartment with the attendant. He gave further instructions to the flight crew that they were to level out at 10,000 feet, keep the landing gear down, lower the flaps to 15 degrees and slow the aircraft to near stall speed at 120 miles per hour. Then, Cooper had the attendant go into the cockpit cabin and close the door.

At 8:13 pm, the fuselage lost pressure. Then, there was a sudden shake in the tail section as if a weight was discharged. The crew called Cooper on the intercom, but he didn’t respond. The Boeing 727 landed in Reno at 10:15 pm and the crew found D.B. Cooper and his money to be long gone.

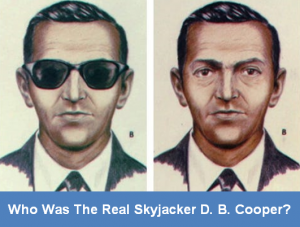

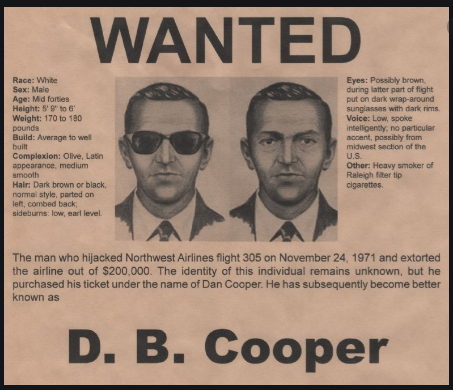

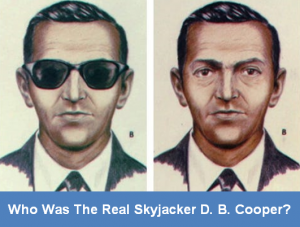

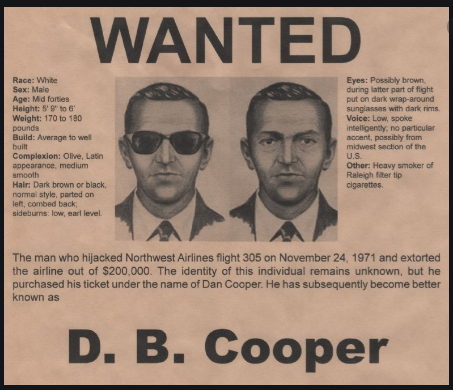

The police and FBI in Portland, Seattle and Reno acted fast. Their priority was to identify Cooper and try to locate him. This was the days before intense video surveillance so all the authorities had was interviewing witnesses who had contact with the man known as D.B. Cooper.

The police and FBI in Portland, Seattle and Reno acted fast. Their priority was to identify Cooper and try to locate him. This was the days before intense video surveillance so all the authorities had was interviewing witnesses who had contact with the man known as D.B. Cooper.

Artist drawings taken at different locations were remarkably similar. The image was a white male in his forties with brown eyes and short, receding hair. His build was between 5’10 and 6 feet with weight estimation at 170-180 lbs. Cooper’s dress was a dark suit jacket and matching slacks, with a white shirt and a black clip-on tie. He wore an overcoat and had only loafers on his feet.

The news of this brazen and bizarre event brought masses of information pouring in. By daylight, air and ground searches pounded the area where they thought Cooper jumped. Agents tracked down suspects and verified alibis. They also processed physical evidence left on the plane.

The investigation was exhaustive. But it wasn’t unproductive. Although D.B. Cooper was never found or identified—officially—there is existing evidence that could solve the case. It might be a matter of time before a break comes and the D.B. Cooper case is cracked through modern forensic technology. Here’s what’s known about the elusive Dan Cooper.

The Physical Evidence

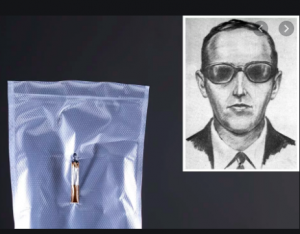

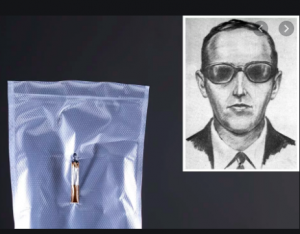

The FBI, along with local police, treated the Boeing 727 like the crime scene it was. They isolated the area Cooper sat at and recovered some items. Of prime importance were 8 Raleigh King-Sized filter-tipped cigarette butts. These were verified by the flight attendant who observed Cooper smoking them.

Forensic examiners lifted fingerprints from the bourbon glass Cooper drank from. They also lifted prints from surrounding surfaces including an in-flight magazine that the attendant saw Cooper flip through. The prints have never been identified even through modern computerized assessments.

Forensic examiners lifted fingerprints from the bourbon glass Cooper drank from. They also lifted prints from surrounding surfaces including an in-flight magazine that the attendant saw Cooper flip through. The prints have never been identified even through modern computerized assessments.

D. B. Cooper left his clip-on tie on the seat. It was sourced as being sold by J. C. Penney and contained a pearl tie clip. From the clip’s position, it appeared to have been placed by a left-handed person. This is consistent with witness descriptions of how Cooper was holding objects and conducting his actions. With forensic advancements, Cooper’s tie would later tell a whole lot more.

The Parachute Evidence

There were two thought schools in the early Cooper investigation stages. One was that he was an experienced parachutist with possible military training. The other was that Cooper was a rank amateur. Experienced parachutists mostly agreed that it was foolhardy—if not suicidal—to jump from a jetliner in those conditions.

When Cooper left the aircraft, it was pitch black, rainy and cold. The air temperature at 10,000 feet was well below zero, and Cooper was wearing nothing but a suit and slip-on shoes. When he demanded the specific parachutes, he made no request for warmer clothes, better boots, a helmet or any gloves.

However, D. B. Cooper was exact about the parachute types. He demanded four packs. Two were main chutes that were back mounted. The other two were reserve or backup packs designed to be harnessed on the chest. Two of the parachutes went out the door with D. B. Cooper, and two stayed behind on the plane.

However, D. B. Cooper was exact about the parachute types. He demanded four packs. Two were main chutes that were back mounted. The other two were reserve or backup packs designed to be harnessed on the chest. Two of the parachutes went out the door with D. B. Cooper, and two stayed behind on the plane.

These parachutes were unique and Cooper knew it. One main, or back-mounted, unit was a civilian sport-diving parachute that was steerable. The other was a military emergency parachute suitable for pilot and aircrew ejection. The civilian parachute had a long and slow opening rate while the military one deployed immediately and would work for low altitude operation.

One reserve parachute complemented the civilian model. The other was termed a “dummy” chute and was more suitable for last-resort operation. Cooper left the civilian-type main and reserve parachutes on the plane. He jumped with the low-altitude escape model on his back and modified the dummy pack to hold his money.

The Bail-Out or Jump Location

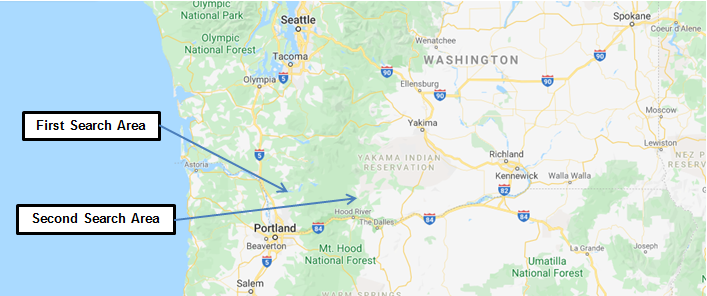

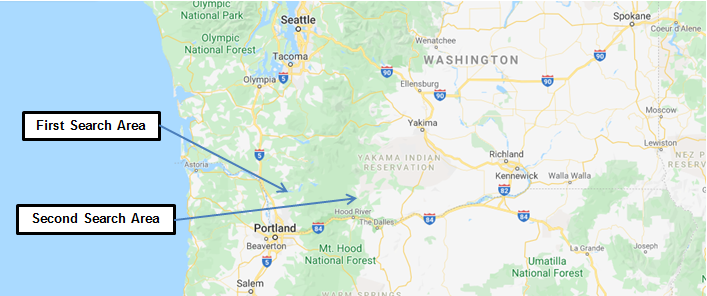

Flight records and crew input estimated D. B. Cooper’s exit-from-the aircraft time at 8:13 pm. This is when they felt the fuselage pressure drop and the shake when presumably his body weight relief changed the flight characteristics and the plane required re-trimming. Given the flight path, speed and distance, the original investigators placed the jump site as being in the Ariel district of southwest Washington near Lake Merwin on the Lewis River drainage.

Searchers extensively covered the Ariel region. They used fixed-wing airplanes, helicopters and submersibles. Hundreds of military staff, police officers and local volunteers scoured the ground on foot, horseback and all-terrain vehicles. They found nothing.

In the spring of 1972, investigators and flight experts reevaluated their location estimate. They realized there was a flight path mistake as the pilots were on manual flight control, not autopilot. With a westerly wind influence, the experts revised their suspicion to believe that Cooper jumped further east over the Washougal River region.

Search efforts focused to the south-south-east of Mount St. Helens. Again, they found no trace of D. B. Cooper or his effects. The man and the money had simply vanished. The big question on everyone’s mind was whether he was alive or dead.

The Boeing 727 Aircraft

It’s obvious that D. B. Cooper, whoever he was, knew more than his parachutes. He also knew his airplanes. Cooper knew the Boeing 727-100 model was ideally suited for a jetliner jump.

The 727 had a very interesting design compared to other popular jets of the era like the 707, 737 and 747. It was tri-engined with all three powerplants mounted high on the rear and not forward on the wings. The 707 also had a unique entry and exit door in the tail.

The rear-entry/exit stairway, combined with the elevated rear engines, made the Boeing 727 about the only commercial passenger jet that a jumper could safely and practically exit. With the rear staircase lowered, it allowed the parachutist to enter the outside and be partially protected from the wind stream. The jumper would also be below the heat and thrust of the engine exhaust. (Click on GIF Image for Animated Bail Out)

The rear-entry/exit stairway, combined with the elevated rear engines, made the Boeing 727 about the only commercial passenger jet that a jumper could safely and practically exit. With the rear staircase lowered, it allowed the parachutist to enter the outside and be partially protected from the wind stream. The jumper would also be below the heat and thrust of the engine exhaust. (Click on GIF Image for Animated Bail Out)

D. B. Cooper also knew things about the staircase operation. He was able to open it while in flight which is not what system was designed to do. The flight attendant who stayed on the Seattle to Reno leg also stated that Cooper asked her a question about the staircase operation that indicated he had technical knowledge of it.

The Portland-to-Seattle Flight Choice

Without question, D.B. Cooper intentionally chose the Northwest Orient Airlines 727 flight from Portland to Seattle. Besides the 727 being the perfect plane to serve Portland, the company’s home base was in Seattle. It was the headquarters city for Northwest Orient and the location where decisions could be quickly made and cash being raised fast.

$200,000 was a lot of money back in 1971. It’s the equivalent of $1.26 million today. That’s not pocket change, but Northwest was able to source that amount and deliver it to Cooper in a two-hour window. In all likelihood, Cooper knew it.

$200,000 was a lot of money back in 1971. It’s the equivalent of $1.26 million today. That’s not pocket change, but Northwest was able to source that amount and deliver it to Cooper in a two-hour window. In all likelihood, Cooper knew it.

D. B. Cooper also knew the topography. In conversations with the attendant, Cooper casually mentioned a landmark in Tacoma that he could see out the window. He also stated he knew McChord Air Force Base was a 20-minute drive from there. It’s also likely Cooper would know that two F-106 fighters were scrambled from McChord and were shadowing him all the time.

Cooper also must have known intimate things about his jump zone. On one hand, it was the dead of night and in a cold climate. A random leap into unknown territory would have been extremely risky for suffering injury or experiencing hypothermia. One the other hand, if Cooper had planned his exit strategy as well as his entrance, then he probably had something prepared for the getaway.

Evidence Turns Up on the Ground

For seven years, there wasn’t hide nor hair seen of D.B. Cooper. The suspected landing regions were combed by professionals from the military and law enforcement agencies as well as folks from the general community. It wasn’t so much D. B. Cooper that the civilian sleuths were interested in. It was the cash.

Most people believed, on the balance of probabilities, that Cooper died in the fall. That meant his bag of money was out there—somewhere. It didn’t hurt the search efforts that Northwest Orient and their insurer offered a large reward for Cooper or the cash’s capture.

Most people believed, on the balance of probabilities, that Cooper died in the fall. That meant his bag of money was out there—somewhere. It didn’t hurt the search efforts that Northwest Orient and their insurer offered a large reward for Cooper or the cash’s capture.

A bit of a break happened in 1978. An airline placard from Flight 305 was found near a logging road in southern Washington State. It was the instruction notice for how to operate the rear stairwell of a Boeing 727. This location jived with the eastern flight path that the aviation experts reassessed and placed in the Washougal River drainage.

A bigger break came in 1980. A much bigger break. A 10-year-old boy was digging along a sandbar bank on the Columbia River downstream from Vancouver, Washington which is near Portland. He found part of D. B. Cooper’s ransom money.

The young fellow spotted a weathered wad of bills. They were all U.S. twenties for a total of $5880. The serial numbers matched the ones recorded by Northwest Orient and their banker.

The young fellow spotted a weathered wad of bills. They were all U.S. twenties for a total of $5880. The serial numbers matched the ones recorded by Northwest Orient and their banker.

The bills were in pretty tough shape. They were worn in a “rounded” pattern that indicated water-sourced erosion rather than being buried or hidden in their original condition. This led investigators to consider the source.

The forensic team eliminated the Lewis River drainage because it poured into the Columbia downstream from the sandbar. The Washougal drainage, however, was upstream. Searchers went back in full force through the Washougal and its tributaries. They came away empty-handed.

The Current Forensic Evidence

Since 1971, there have been tremendous advances in forensic science. The biggest one is DNA genotyping and that’s been done in the D. B. Cooper case. The results—or lack of results—are interesting.

There were biological deposits on the J.C. Penney tie Cooper left on the plane. Two small samples and one larger sample allowed the forensic lab to build a male profile. The best guess is the bio-material was saliva.

There were biological deposits on the J.C. Penney tie Cooper left on the plane. Two small samples and one larger sample allowed the forensic lab to build a male profile. The best guess is the bio-material was saliva.

And the best guess is that the profile is from the real D. B. Cooper. But that’s just an educated guess because this tie could have been contaminated by another male who borrowed the tie from Cooper or sold it to him. This avenue is weak, but it’s the only DNA path the forensic team has.

But what about the Raleigh King-Sized filtered tip cigarette butts? The attendant saw Cooper with these in his mouth. Surely it would be his saliva and DNA on those?

Well, no one knows what happened to Cooper’s butts. In deep-diving the Cooper case literature, it looks like the FBI lost the entire eight cigarette butts. Internally, the blame bonces between the Reno team who recovered them and the Las Vegas lab who received them. Buck-passing also goes from Vegas to Seattle but, the truth is, the cigarette butts are unaccountable and they have been gone for a long, long time.

Well, no one knows what happened to Cooper’s butts. In deep-diving the Cooper case literature, it looks like the FBI lost the entire eight cigarette butts. Internally, the blame bonces between the Reno team who recovered them and the Las Vegas lab who received them. Buck-passing also goes from Vegas to Seattle but, the truth is, the cigarette butts are unaccountable and they have been gone for a long, long time.

There’s still a bit of a shining light in the D. B. Cooper forensic closet. In 2008, forensic specialists used a highly-sophisticated scanning electron microscope to look inside Cooper’s tie. What they found was telling.

D. B. Cooper’s tie was significantly contaminated at the near-molecular metal by some very rare and unusual metals. The microscope picked up traces of cerium, strontium sulfide and pure titanium as well as other tidbits of bismuth and aluminum. That meant the tie had to have been in a metal shop that manufactured high-tech materials.

The prominent place where these materials amassed was in the Boeing factory near Seattle. At the time, this combination of micro-materials was only used in making the prototype in Boeing’s supersonic transport development project. Insiders said that only managers and engineers wore ties in the work area where they’d be exposed to airborne trace metals.

The D. B. Cooper Suspect List

The FBI investigated over 1,000 suspects during their years of probing. Some leads were weak. Others were strong. And, some still haven’t been completely ruled out.

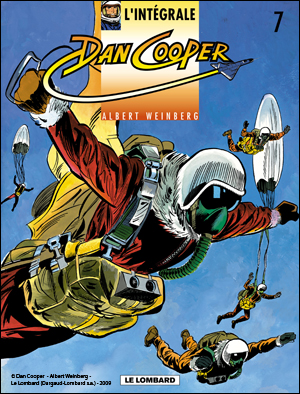

But before naming names, there’s a big curiosity many people have. That’s where did the handles D. B. Cooper and Dan Cooper come from? There seems to be some confusion.

In the official investigation, there’s no such name as D. B. Cooper. The suspect used the name Dan Cooper on the flight manifest, and that is undoubtedly an alias.

Somehow, the Portland media, in a rush for a deadline, got the name wrong and put it on the wire as D. B. Cooper. The name stuck and now holds legendary status.

Somehow, the Portland media, in a rush for a deadline, got the name wrong and put it on the wire as D. B. Cooper. The name stuck and now holds legendary status.

There’s an interesting background to the “Dan Cooper” alias, though. In the late 1960s, a Belgium comic book publisher ran a series about a Canadian Air Force test pilot who did a lot of thrill-seeking stuff. Bailing out of airplanes with parachutes was one. The magazines were never printed in English—only French—and the hero’s name was Dan Cooper.

When the FBI closed the file they called NORJAK for Northwest Hijacking, they publicly indicated they’d done their best to eliminate all reasonable suspects. However, they left the door open to re-investigating leads should something new and good come in.

Here are the top names who the FBI looked into:

Kenneth Christianson was a U.S. Army paratrooper who joined Northwest Orient as a mechanic and then went on to be a flight attendant and purser. He served on 727s and knew them intimately. Christiansen was left-handed, smoked and liked bourbon. He died in 1994 and allegedly left a deathbed confession

Jack Coffelt was a conman and government informant. He allegedly made a jailhouse confession and was a dead-ringer in looks to the D. B. Cooper sketches. Coffelt was in Portland on November 24, 1971, and showed up a few days later with leg injuries that he said were from a skydiving accident. He died in 1975.

Lynn Doyle (LD) Cooper was a Korean War veteran. After he died in 1999, his family members came forward with their belief that “LD”, as they called him, was D. B. Cooper. The family stated he was obsessed with the Dan Cooper comics and images of LD were similar to the suspect drawings. LD Cooper lived in the Washougal River drainage and survived a questionable and unwitnessed accident at the time of the skyjacking. Familial DNA testing does not match the Cooper tie.

William Gossett died in 2003. According to the FBI’s lead NORJAK investigator at the time, “The circumstantial evidence is real strong, and I feel we got the right guy”. Gossett was an army paratrooper with extensive night and low-level jumping experience. He also was an exact physical match to the eyewitness reports of D. B. Cooper.

Richard McCoy was an experienced military parachutist. He was also caught after highjacking a 727 airplane and bailing out over Utah in 1974. McCoy’s modus operandi was an exact replica of the Cooper skyjacking. He also looked like Cooper. Whether he was a copycat or the real McCoy, we’ll never know. Richard McCoy escaped from jail and was shot to death in a gunfight with the cops.

Duane Weber could have been D. B. Cooper’s doppelganger. Before he died in 1995, Weber confessed to his wife that he was the real D. B. Cooper. He even provided her with key-fact evidence like fingerprint placement on the aft staircase rails. The FBI tested Weber’s familial DNA and eliminated it as being the donor on the tie.

The FBI Theory on Who D. B. Cooper Really Was

Many FBI agents worked on the NORJACK file. Over the years, agent opinions have waffled back and forth on who D. B. Cooper really was and if he survived the nighttime jump in frigid conditions. The majority seem to think Cooper died in the fall.

Others are not so sure. They point to five other 727 hijackings where the perpetrator jumped in midair and lived to tell about it. Some feel it might be crazy, but it’s been tried and it worked. They say there’s every reason to believe Cooper succeeded.

Others are not so sure. They point to five other 727 hijackings where the perpetrator jumped in midair and lived to tell about it. Some feel it might be crazy, but it’s been tried and it worked. They say there’s every reason to believe Cooper succeeded.

FBI Agent Larry Carr was the last investigator assigned to the D. B. Cooper case. He closed the file in 2016. Here’s Agent Carr’s take on the matter:

“I think it’s highly unlikely Cooper survived the jump. But he came from somewhere and something. And that is what we wanted to know. My profile of Cooper is that he served in the Air Force and at some point was stationed in Europe. That’s where he may have become interested in the Dan Cooper comic books.

I think he worked as a cargo loader on military planes, giving him knowledge and experience in the air-drop cargo aviation industry which was still in its infancy back in 1971. Because his job would have him throwing cargo out of planes, Cooper would have worn an emergency parachute in case he fell out. Certainly, he would have been trained in parachuting and would have experienced a few actual jumps. This would have provided him with a working knowledge of parachutes, but not necessarily the functional knowledge to survive a jump under the conditions he did.

I think he worked as a cargo loader on military planes, giving him knowledge and experience in the air-drop cargo aviation industry which was still in its infancy back in 1971. Because his job would have him throwing cargo out of planes, Cooper would have worn an emergency parachute in case he fell out. Certainly, he would have been trained in parachuting and would have experienced a few actual jumps. This would have provided him with a working knowledge of parachutes, but not necessarily the functional knowledge to survive a jump under the conditions he did.

I think he arrived in Seattle after he discharged from the military and might have got a job in the Boeing factory. That’s where the metal traces in the tie likely came from. It’s possible that he lost his job during an economic downturn that happened in the aviation industry in 1970 and 1971.

If he was a loner, or with little family, no one would have missed him after he was gone.”

Did the mysterious Dan (D. B.) Cooper die in his skyjacking? Or did he live to see another day? What are your thoughts?

* * *

Post Publication Note 07April2020: A DyingWords follower sent a link to their website that developed an interesting theory purporting the late William Smith might have been the real D. B. (Dan) Cooper. There are some remarkable similarities and it appears the FBI never investigated Smith as a suspect. The website host gave the FBI their information on Smith in 2018 along with Smith’s known fingerprints from his US Army service file. So far, there’s been no response from the FBI, presumably because the NORJACK case is a closed file. Here’s the link to the William Smith suspect website and a comparison photo of an older William Smith to the artist drawing: https://dbcooperhijack.com/

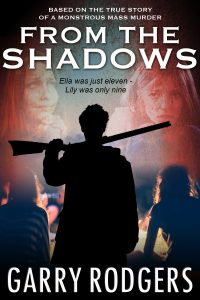

From The Shadows is based on the horrific true crime story of grandparents, Ed and Patricia Bartley, parents Gunner and Trisha Jephsen, and their two prepubescent girls who disappeared on a Vancouver Island camping trip. Ella was just eleven. Lily was only nine.

From The Shadows is based on the horrific true crime story of grandparents, Ed and Patricia Bartley, parents Gunner and Trisha Jephsen, and their two prepubescent girls who disappeared on a Vancouver Island camping trip. Ella was just eleven. Lily was only nine. ~ From The Shadows is Garry Rodgers’ best book yet. Garry keeps getting better all the time.

~ From The Shadows is Garry Rodgers’ best book yet. Garry keeps getting better all the time.