The name “Adolf Hitler” is synonymous with evil. Pure evil. Hitler, or the Fuhrer as he self-titled, ruled Germany as chancellor and dictator from the rise of Nazism in 1933 until his death by suicide in 1945. During that time, millions of civilians and soldiers died and the Motherland was destroyed — a truly atrocious era in human history. Horrific as that time was, today there’s a terrible possibility a new monster could arise from Adolf Hitler’s remains.

The name “Adolf Hitler” is synonymous with evil. Pure evil. Hitler, or the Fuhrer as he self-titled, ruled Germany as chancellor and dictator from the rise of Nazism in 1933 until his death by suicide in 1945. During that time, millions of civilians and soldiers died and the Motherland was destroyed — a truly atrocious era in human history. Horrific as that time was, today there’s a terrible possibility a new monster could arise from Adolf Hitler’s remains.

From the moment Adolf Hitler expired, rumors circulated about what really happened to the Fuhrer’s body. Many witnesses were at Hitler’s death scene. Most saw his deceased form, and some admitted to help dispose of Hitler’s earthly evidence. Despite sworn statements and hard medical facts, few details were released to the Allies and the western world. That was because Russians did the investigation. Red Army Intelligence officers processed forensics that included autopsying and conclusively identifying Hitler’s cadaver.

Because of a lack of released information, speculation of Hitler’s survival soon started. Concocted conspiracy theories began, and there were sightings of the Fuhrer reported on every continent including a secret submarine base near Antarctica. Nazi hunters followed clues across Europe, in Asia, Africa, America and deep into Argentina. None paid off because the truth was the Russians had Hitler all along.

Because of a lack of released information, speculation of Hitler’s survival soon started. Concocted conspiracy theories began, and there were sightings of the Fuhrer reported on every continent including a secret submarine base near Antarctica. Nazi hunters followed clues across Europe, in Asia, Africa, America and deep into Argentina. None paid off because the truth was the Russians had Hitler all along.

The truth is also that Hitler’s corpse made a remarkable journey from one hiding spot to another. He was buried and dug-up at least five times over a twenty-five year period. Today, tangible parts of Adolf Hitler still exist, and that leads to a modern biological possibility the Fuhrer could live again. Here’s the terrible truth about Adolf Hitler’s remains.

* * *

Adolf Hitler entered the world in 1889. His birthplace was near Linz which was then part of the Austrian-Hungarian alliance. Hitler moved to Germany in 1913 and worked as an aspiring architect but amounted to no more than a starving artist.

He served in the German Army during World War 1 and rose to a corporal rank. He was injured while running messages and spent most of the First World War on the sidelines. Following Germany’s surrender, Hitler immersed in trade union politics with the German Workers Party and soon got himself in trouble.

He served in the German Army during World War 1 and rose to a corporal rank. He was injured while running messages and spent most of the First World War on the sidelines. Following Germany’s surrender, Hitler immersed in trade union politics with the German Workers Party and soon got himself in trouble.

Hitler was jailed as a political prisoner after he led a failed coup. His lock-up during 1923 and 1924 gave him time to write Mein Kampf (My Struggle) which was his manifesto outlining his plan to gain dictatorial power in Germany and expand Aryan racial interests. Hitler also met Rudolf Hess who had significant influence in solidifying anti-Jewish hatred in Hitler’s psyche.

By the early 1930s, Adolf Hitler attained sufficient control through the National Socialist Party which were the Nazis. Hitler surrounded himself with particularly nasty men and used brute force to gain and maintain authority. Some were ideological psychopaths such as Heinrich Himmler. Others, like Herman Goering, were crass opportunists.

Hitler managed to establish massive support from the German population which included the Caucasians and excluded other races and cultures, especially the Jews. He formed plans to expand Germany’s empire and gain space for the blond-haired, blue-eyed pure Aryans. But, his 1939 action of annexing Poland started the Second World War and began his undoing.

One of Hitler’s massive mistakes was declaring war on Russia. From a historical point, there was no need to do this for Hitler to execute his manifesto. It seems Hitler went slowly mad and his delusions caused him to fatally overextend his armed forces’ capacity and the world turned on him through an unlikely Russian and western alliance.

By April of 1945, the war was nearly over and Hitler denied it. He was probably insane by this time which is backed-up by accounts of his inner circle who stayed with Hitler in his Berlin bunker until the Russians arrived. There were reports of Hitler collapsing in tearful rages and hysterically ordering non-existent army units into combat action.

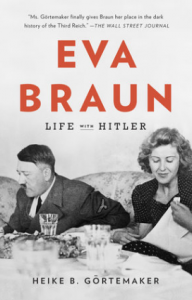

On April 30, 1945, Adolf Hitler married his long-time mistress, Eva Braun, in the Fuhrer bunker. After a minor champagne celebration and dictating his last will and testament, Hitler and Braun retired to their chambers and committed joint suicide. Exactly how they did it and what became of their bodies turned into a world-class mystery. Some describe it as a parlor game full of crazy conspiracies.

On April 30, 1945, Adolf Hitler married his long-time mistress, Eva Braun, in the Fuhrer bunker. After a minor champagne celebration and dictating his last will and testament, Hitler and Braun retired to their chambers and committed joint suicide. Exactly how they did it and what became of their bodies turned into a world-class mystery. Some describe it as a parlor game full of crazy conspiracies.

The best evidence of what really happened to Hitler and Braun comes from two sources. One is eyewitnesses who were in the bunker at the time. The other is scientific material carefully collected by the Russian government. The first information pool has the usual witness fallibilities. The second source has credibility issues due to Russian misinformation, concealment, and cover-ups.

There is absolutely no doubt Adolf Hitler died on April 30, 1945. That is uncontested by any credible opinion. Most accounts have Hitler using the “pistol and poison” method where he ingested prussic acid, or hydrogen cyanide, while putting a handgun in his mouth and pulling the trigger. All accounts indicate Evan Braun was not shot. Rather, she also took a cyanide dose.

Hitler clearly expressed his wish to have their bodies cremated. He’d learned of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini’s public execution where Mussolini’s body was hung by the feet and mutilated by the crowd. Adolf Hitler did not want that happening to him. He specifically instructed his staff to take his body out of the bunker and set in on fire in the garden.

This act is well recorded and supported by now-released evidence. Hitler’s aides poured some sort of petroleum fuel over the Fuhrer and Eva Braun. However, they were unable to create sufficient heat to consume the corpses and the cadavers were only charred.

This act is well recorded and supported by now-released evidence. Hitler’s aides poured some sort of petroleum fuel over the Fuhrer and Eva Braun. However, they were unable to create sufficient heat to consume the corpses and the cadavers were only charred.

There were several attempts to increase the inferno, but time ran out. The Russians were on their doorstep and lobbing artillery rounds into the garden and at the bunker. Aides hastily dug a shell crater into a shallow grave and covered up Hitler and Braun’s burnt bodies.

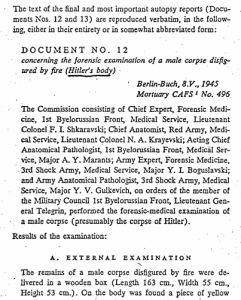

The bunker occupants surrendered and quickly disclosed where Hitler and Braun lay buried. Russian medical experts arrived on May 4, 1945, and exhumed the grave. They took both bodies to a facility at Buch in Berlin and stored them above ground. Two Russian pathologists performed autopsies on May 10, and their report was publicly released under the Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act in 2000.

Hitler and Braun were superficially scorched to the point of visual non-recognition. However, they were skeletally intact which included their organs being suitable for dissection. Braun showed no bullet wound but did exhibit post-mortem shrapnel damage. One pathologist noted this probably happened as an artillery round exploded while she was on fire. Glass shards and cyanide traces were in her mouth, and they listed Eva Braun’s cause of death as suicide by poison.

Adolf Hitler showed no conclusive sign of disease or any sudden medical event. As rumors always said, Hitler only had one testicle. His brain was biologically unremarkable, but it was traversed by a bullet passage. The pathologists could not identify an entrance wound and theorized it was probably through the mouth. There was also no notable exit wound or bullet slug itself. The report says Hitler’s upper cranial bone was missing, and they assumed it was blown off by the gunshot force.

Adolf Hitler showed no conclusive sign of disease or any sudden medical event. As rumors always said, Hitler only had one testicle. His brain was biologically unremarkable, but it was traversed by a bullet passage. The pathologists could not identify an entrance wound and theorized it was probably through the mouth. There was also no notable exit wound or bullet slug itself. The report says Hitler’s upper cranial bone was missing, and they assumed it was blown off by the gunshot force.

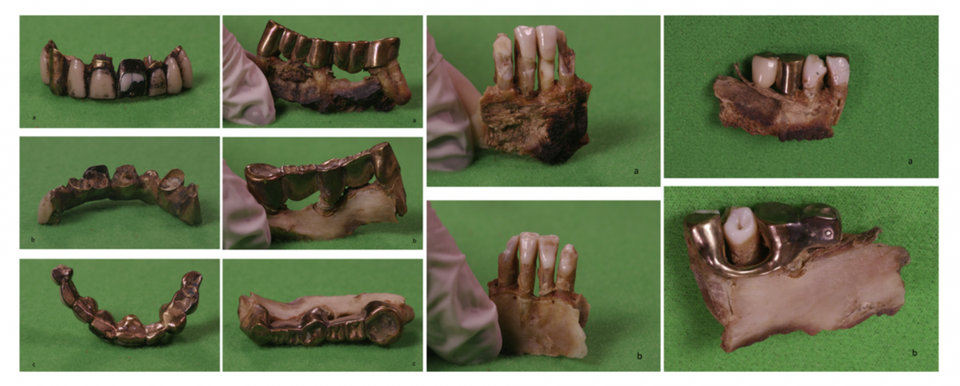

The pathologists conclusively found glass shards and cyanide traces in the Fuhrer’s mouth. They listed his cause of death as a combination of cyanide poisoning and a gunshot wound to the head. Something else they discovered in Hitler’s mouth was crucial to identifying his body. That was Adolf Hitler’s unmistakable dentition.

Hitler’s teeth were in terrible condition. His upper and lower mandibles were a mess of bridges and crowns with a sprinkling of natural enamel that enclosed tooth pulp. His gums were inflamed, and he had several extraction gaps that weren’t replaced. It was an odontologist’s dream when it came to making a postmortem identification.

The Russian pathology team located Hitler’s dentist and assistant who were thoroughly familiar with every part of the Fuhrer’s mouth. They viewed the dental work from the cadaver and produced Hitler’s complete records. They established there was absolutely no doubt whatsoever these dental works belong to the now-deceased Adolf Hitler.

Joseph Stalin, the Russian dictator, wasn’t so sure. Stalin was paranoid that his nemesis Hitler would come to haunt him by people believing Hitler was alive and hidden or having his body become a future Nazi shrine. Stalin stalled and ordered Hitler’s body temporarily buried with the dental work brought to Moscow for his inspection.

It’s not clear from historical records where Hitler’s body was temporarily interred. It seems he was stored in the Russian-occupied sector of Berlin. Once Stalin was satisfied Hitler was dead, and the dental work was conclusive identification, he began a misinformation campaign to deny this. Stalin’s motives for fooling the west have gone to the grave with him, but Stalin wasn’t finished with Hitler’s body.

On June 3, 1945, Stalin ordered Hitler’s remains exhumed from temporary storage and moved to a highly-secret and secluded spot. This was in the Brandenburg forest area southwest of Berlin. Hitler, and presumably Braun as well, were buried in wooden caskets which were more like shipping crates. They lay undisturbed for several months until Stalin had a change of plans.

For whatever reason, Stalin ordered Hitler dug-up again. On February 21, 1946, Stalin directed that Hitler be put under the ground at a parade square inside a Russian-held military base at Magdeburg, Germany. This spot was southwest of Brandenburg, but in a high-traffic area instead of a remote forest.

Joseph Stalin died in 1953. Russia carried on as the Soviet Union and entered the cold war. By 1970, Russia began turning occupied territory over to the East German government which was communist friendly. That included the Magdeburg base going back into German hands.

Yuri Andropov, who went on to be the Soviet Union leader, was the KGB head in the early 70s. Andropov knew Hitler’s body was under the Magdeburg parade square, and the last thing he wanted was a future German regime breathing life into Hitler’s memory by turning that site into a Neo-Nazi Mecca. Andropov had Hitler exhumed again and finally dealt with.

In the middle of the night on April 3-4, 1970, a secret shovel squad extracted what was left of Adolf Hitler’s bones and burned them. There are conflicting stories about what happened. Andropov is on public record stating the ashes were scattered in the nearby Elbe River. Work-party members state the bones were so dry that they vanished in smoke. And a few reports hint that Adolf Hitler was dumped into the city sewer system.

In the middle of the night on April 3-4, 1970, a secret shovel squad extracted what was left of Adolf Hitler’s bones and burned them. There are conflicting stories about what happened. Andropov is on public record stating the ashes were scattered in the nearby Elbe River. Work-party members state the bones were so dry that they vanished in smoke. And a few reports hint that Adolf Hitler was dumped into the city sewer system.

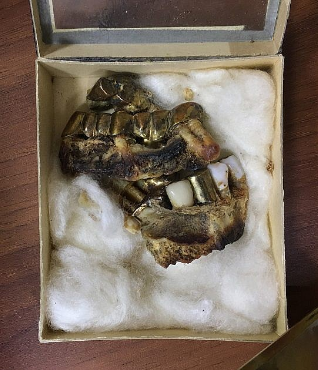

What finally took place with Hitler’s cadaver may never be known. However, there’s one thing for certain. Adolf Hitler’s teeth remain locked in a Kremlin vault. They’re resting there today.

What’s also certain is Hitler’s natural teeth contain his DNA. Those molecules stay preserved in the pulp. Hitler’s biological profile is encased within the enamel practically forever, and DNA can be cloned. Cloning Adolf Hitler was the plot in the 1978 blockbuster The Boys From Brazil. Back then, it was science fiction. Today, technology of DNA extraction and cloning zygote embryos into a surrogate mother is not sci-fi. It’s very, very, very real.

All it would take is some evil crackpot doctor like Joseph Mengele to steal Hitler’s tooth, saw it open, and start cloning away. That’s the terrible truth about Adolf Hitler’s remains.

Here are more American stats from the

Here are more American stats from the  You’re probably wondering what got me going on capital punishment and why the headline

You’re probably wondering what got me going on capital punishment and why the headline

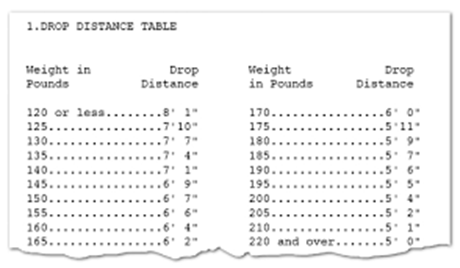

The force (in foot pounds) of the drop is critical and is determined by the physical stature of the executee, primarily his weight. In general, the heavier the person, the shorter the drop, and conversely, the lighter the person the longer the drop. Generally, weights as low as 120 pounds result in a force of some 950 foot pounds where weights over 220 result in some 1100 foot pounds. A drop of too short a distance will result in a condition where the spinal cord is not severed and the executee will not go into shock and will be conscious during the strangulation period. A drop of too long a distance will result in decapitation. Both conditions are not humane. In general, execution requirements will never result in an execution where the inertia of the drop will greatly exceed 1600 foot pounds or be less than 900 foot pounds. In all cases, it is better to utilize an established formula.

The force (in foot pounds) of the drop is critical and is determined by the physical stature of the executee, primarily his weight. In general, the heavier the person, the shorter the drop, and conversely, the lighter the person the longer the drop. Generally, weights as low as 120 pounds result in a force of some 950 foot pounds where weights over 220 result in some 1100 foot pounds. A drop of too short a distance will result in a condition where the spinal cord is not severed and the executee will not go into shock and will be conscious during the strangulation period. A drop of too long a distance will result in decapitation. Both conditions are not humane. In general, execution requirements will never result in an execution where the inertia of the drop will greatly exceed 1600 foot pounds or be less than 900 foot pounds. In all cases, it is better to utilize an established formula. Up until very recently Execution was an Art employed only by the “Executioner”. It is only now becoming a Science with the Training and Certification of other types of Execution Technicians (i.e. Lethal Injection and Electrocution). Those persons carrying out the Protocol and Procedures in this Manual shall be Trained and Certified as Hanging Technicians.

Up until very recently Execution was an Art employed only by the “Executioner”. It is only now becoming a Science with the Training and Certification of other types of Execution Technicians (i.e. Lethal Injection and Electrocution). Those persons carrying out the Protocol and Procedures in this Manual shall be Trained and Certified as Hanging Technicians. Means of Releasing

Means of Releasing Hood.

Hood.

One (1) or more Certified Hanging Technicians

One (1) or more Certified Hanging Technicians 2.

2.  8.

8.  2. Install the Body Restraint around the Executee’s waist and tightly bind his wrists to the restraint. (His arms may be restrained either in the front or the back.) If necessary, utilize the Collapse Frame.

2. Install the Body Restraint around the Executee’s waist and tightly bind his wrists to the restraint. (His arms may be restrained either in the front or the back.) If necessary, utilize the Collapse Frame. 7. The Trap Door Shall Open and the Executee Shall Drop. On order from the Warden some eight minutes after the release mechanism was thrown, the attending doctor shall examine the Executee for heart death.

7. The Trap Door Shall Open and the Executee Shall Drop. On order from the Warden some eight minutes after the release mechanism was thrown, the attending doctor shall examine the Executee for heart death.

Length of loops: make loop as shown from Standing Part to Running End. A to B should be approximately eighteen (18) inches, and from C to Running End should be approximately thirty-five (35) inches. Wrap running end for six (6) turns. No extra rope should remain.

Length of loops: make loop as shown from Standing Part to Running End. A to B should be approximately eighteen (18) inches, and from C to Running End should be approximately thirty-five (35) inches. Wrap running end for six (6) turns. No extra rope should remain.

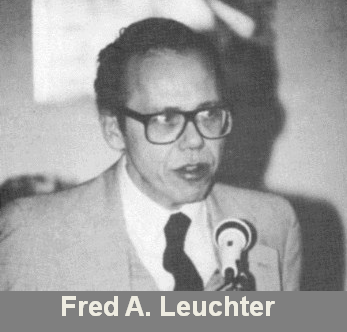

Leuchter was charged in Massachusetts with having misrepresented himself to penitentiaries as an engineer, despite having no relevant qualifications; Leuchter plea bargained with state prosecutors, and received two years probation. He has also been accused of running a “death row shakedown”, in which Leuchter threatened to testify for the defense in capital cases if he was not given contracts for his services by that state.

Leuchter was charged in Massachusetts with having misrepresented himself to penitentiaries as an engineer, despite having no relevant qualifications; Leuchter plea bargained with state prosecutors, and received two years probation. He has also been accused of running a “death row shakedown”, in which Leuchter threatened to testify for the defense in capital cases if he was not given contracts for his services by that state.