Nuclear weapons are the most destructive devices ever devised by human beings. By conservative estimates from ArmsControl.org and the Federation of American Scientists, there are 12,685 known nuclear warheads in the world’s arms inventory—probably far more. Although there’ve only been two actual combat nuclear deployments in history, hundreds of test activations took place. No one truly knows how many near-miss incidents happened, but we do know of thirteen terribly close calls with nuclear weapon accidents.

Nuclear weapons are the most destructive devices ever devised by human beings. By conservative estimates from ArmsControl.org and the Federation of American Scientists, there are 12,685 known nuclear warheads in the world’s arms inventory—probably far more. Although there’ve only been two actual combat nuclear deployments in history, hundreds of test activations took place. No one truly knows how many near-miss incidents happened, but we do know of thirteen terribly close calls with nuclear weapon accidents.

By definition, a near-miss is a “narrowly avoided collision, discharge or other accident”. In nuclear weapon terms, that’d be closely avoiding unintentionally setting off an explosion—an explosion with unfathomable consequences. So how is it that people get so careless when handling an instrument of Armageddon? The answer seems to lie in human nature.

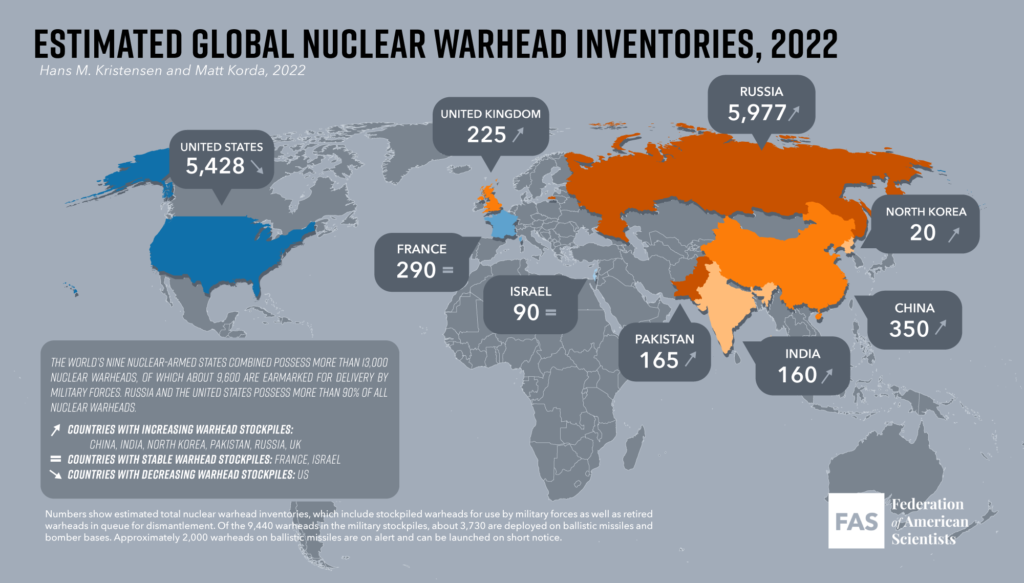

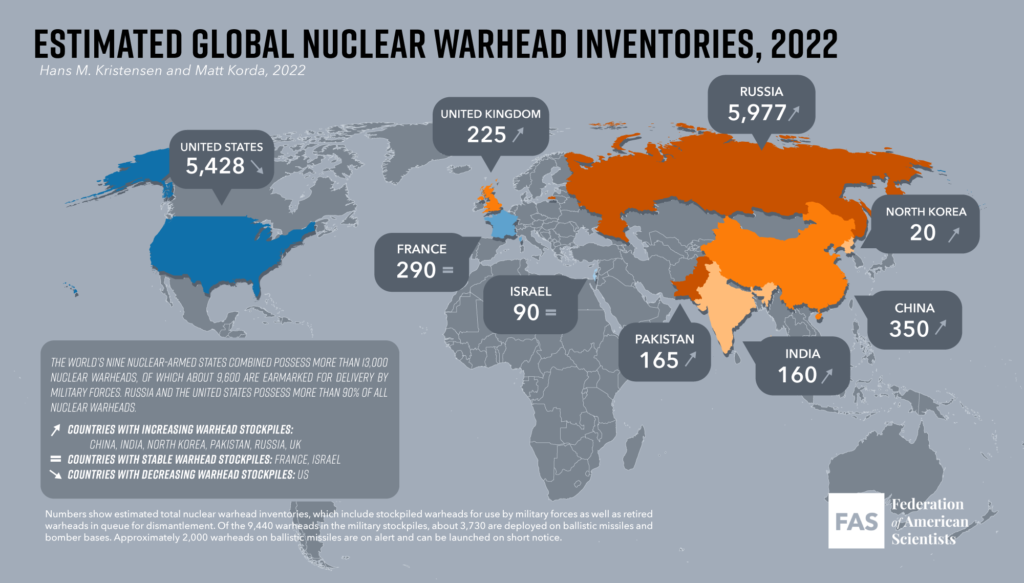

The world has eight countries with known nuclear arsenals. By alphabetical order, that’s China, France, India, Israel, Pakistan, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Three more states have active nuclear weapon acquisition and development programs—Iran, North Korea, and Syria. There’s a lot of effort by “responsible” nuclear weapon powers to curtail the rogue countries before they become more of a menace.

Two international agreements regulate the world’s nuclear-equipped countries. One is the Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) of 1968. The other is the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) of 1996. They divide the countries into three categories: Nuclear-Weapon States, Non-NPT Nuclear Weapons Possessors, and States of Immediate Proliferation Concern. According to ArmsControl.org, here’s where they fit and what they apparently have.

Nuclear Weapon States

- China — 350 warheads

- France — 290 warheads

- Russia — 5977 warheads

- United Kingdom — 225 warheads

- United States — 5428 warheads

Non-NPT Nuclear Weapons Possessors

- India — 160 warheads

- Israel — 90 warheads

- Pakistan — 165 warheads

States of Immediate Proliferation Concern

- Iran — No confirmed warheads but in active development

- North Korea — Known to possess but unknown quantity estimated at 20-30 warheads

- Syria — No confirmed warheads but in active development

Incidentally, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine inherited nuclear bombs upon the Soviet Union break-up. They returned their stockpiles to Russia, but it’s feared some nuclear devices are unaccounted for and open to terrorist possession. South Africa had a nuclear weapon program with active warheads, but they disbanded it. Argentina, Brazil, South Korea, and Taiwan also stopped their nuclear development programs.

Different Nuclear Weapon Types

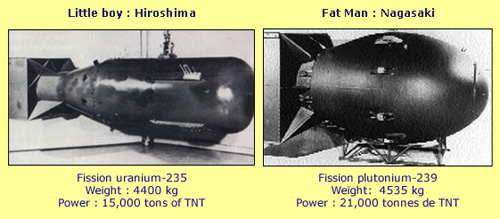

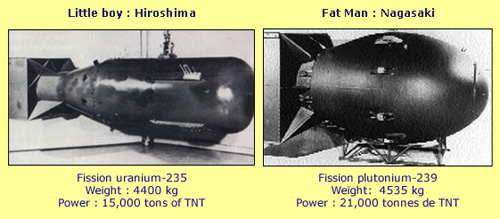

Before getting into the thirteen terribly close calls with nuclear weapon accidents, it’s worth a review of what these weapons of mass destruction really are. Most people are aware that nuclear weapons arrived at the end of World War II when America dropped two atomic bombs on Japan. These were first-generation devices. Little Boy was a uranium fission atomic bomb that destroyed Hiroshima, and Fat Man was a plutonium fission A-bomb that caused Nagasaki’s destruction.

Fat Man and Little Boy were basic A-bomb nuclear weapons that drew energy by splitting plutonium and uranium atoms through a fission process. They weren’t the tremendously-powerful thermonuclear hydrogen bombs that use a primary fission activation to cause nuclear fusion from hydrogen atoms. A fusion-activated H-Bomb uses a fission reaction to release massive energy contained in hydrogen gas.

The two nuclear bombs dropped on Japan were puny compared to today’s extremely energetic thermonuclear weapons. The Japanese destructors held a power equivalent to approximately 20,000 tons of TNT each. Thermonuclear bombs start at about 1/10 million tons of TNT and go up. This energy gets measured in the terms of kilotons (KT) which is 1,000 tons of TNT and megatons (MT) or 1 million TNT tons.

Today, a small-yield nuclear bomb such as a W76 battlefield tactical nuclear weapon would have a 100 KT explosive power. A larger-capacity B83 nuclear bomb would release 1.2 MT in power. Big or small, both designs are enormously destructive and would be devastating if discharged. It’s certainly nothing to risk having an accident with.

Nuclear Weapon Accidents — Broken Arrow

But, accidents do happen with nuclear weapons. They have, and likely will continue, as long as there’s a human element handling them. The United States military has a public record of accidents they’ve experienced with nuclear weapons.

It’s called Broken Arrow. Officially, Broken Arrow lists 32 specific incidents where American nuclear bomb handling went beyond safe handling parameters. Some speculate there are way more—possibly hundreds that haven’t been reported or, worse, covered up. Here are the “official” parameters a nuclear weapon incident/accident must have to make the Broken Arrow list.

- Accidental or Unexplained Nuclear Detonation

- Non-Nuclear Detonation or Burning a Nuclear Weapon

- Radioactive Contamination

- Nuclear Asset Lost or Misplaced in Transit

- Jettison of Nuclear Weapon or Component

- Public Hazard, Actual or Implied

The military loves its code words and phrases. They use Empty Quiver for having a nuclear bomb stolen from them. Dull Sword refers to minor nuclear arms incidents like a malfunctioning vehicle hauling a nuclear bomb. Faded Giant is a failing nuclear reactor. And NucFlash is an intentional or unintentional discharge that starts a nuclear war.

The Union of Concerned Scientists is a watchdog keeping track of close calls with nuclear weapons. They say since the nuclear age started, political and military leaders faced a daunting challenge with their nuclear bomb program. They wanted it free of accidents but still wanted bombs immediately available when and if needed.

So how secure are nuclear weapons against accidental firings, incidental loss, and damage from careless root causes? Well, the good news, they say, is that there hasn’t been a single reported incident where a nuclear or thermonuclear bomb actually went off by accident. The bad news, they report, is there’ve been many, many close calls where accidents and errors nearly nuked us. Here are thirteen terribly close calls with nuclear weapon accidents.

Thirteen Terribly Close Calls With Nuclear Weapon Accidents

13. February 14, 1950 — A U.S. Air Force B-36 bomber en route from Alaska to Texas experienced catastrophic mechanical failure. Most of the crew parachuted out and survived, although the plane crashed and burned in the British Columbia coastal mountains. The one 1-MT Mark 4 nuclear bomb on board was jettisoned into the Pacific Ocean for safety sake. Despite a massive search, the operational nuclear warhead has never been recovered. It’s still out there, armed and waiting to go off.

12. March 11, 1958 — A U.S. Air Force B-47 Stratojet left Savanah, Georgia during a storm. It carried a 1-MT Mark 6 nuclear bomb, and the violent turbulence caused a crew member in the bomb bay to grab on for stability. He accidentally pulled the nuke’s emergency release pin which sent the bomb earthward. It landed at Mars Bluff in a children’s playhouse near three little kids. The bomb failed to detonate but caused a fire that burned down the family home. Fortunately, no one was injured although the children were stunned by the impact concussion.

11. May 22, 1957 — A U.S. Airforce B-36 bomber ran into bad weather over Albuquerque, New Mexico. It had a 10-MT Mark 17 hydrogen bomb in its bay that was accidentally released by a crew member who grabbed the bomb jettison lever to steady himself. The bomb hit the ground with enough force to leave a 12-foot deep by 25-foot wider crater in the desert sand. It didn’t blow up because the fissionable plutonium activator failed to activate. The official report noted that the Mark 17 was the largest nuclear bomb in the American arsenal.

10. March 10, 1956 — A U.S. Air Force B-47 left Florida for Morocco. Somewhere over the Mediterranean Sea, the plane simply vanished. It disappeared. There was no distress call, and no wreckage was ever found. In its bay was one 3.4 MT Mark 15 nuclear bomb as well as an undisclosed number of dismantled nuclear bomb parts. No sign of the plane, its nuclear bomb, or the spare parts ever surfaced.

9. September 19, 1980 — Near Damascus, Arkansas a military personnel working in a Titan Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) silo dropped a wrench down the tube and damaged the fuel tank on a Titan II rocket. The leak caused an uncontrollable fire which destroyed the silo and its contents. On top of the Titan missile was a 9 MT W-53 nuclear warhead. It failed to go off but was burned beyond salvage. Should it have exploded, the blast may have set off a chain reaction blowing up 17 other nuclear bombs in the silo complex.

8. January 24, 1961 — A U.S. Strategic Command B-52 bomber experienced a mid-air collision while attempting to refuel with a KC-135 Flying Tanker near Goldsboro, North Carolina. Both jets broke apart and crashed. The B-52 held two 3.4 MT hydrogen bombs that jettisoned under parachute control. One chute failed and the bomb hit the ground at 700 mph. The other’s chute worked and let the bomb down slowly where it got hung up in a tree. Neither thermonuclear device exploded, but the investigation revealed the arming sequence actually activated on the second bomb that was stopped by the tree. It was only a simple switch with two little wires that prevented a major nuclear disaster.

7. July 27, 1956 — At Lakenhearth AFB in the United Kingdom, an American B-47 bomber on a touch-and-go training mission lost control. It plowed into a UK missile silo containing three 3 MT Mark 6 nuclear warheads. The silo, or “igloo” as it’s called, caught fire and burned. Once out, the investigation team found that the warheads were still operational and one bomb’s detonator had been sheared off in the impact. No one could clearly explain why it failed to go off as it should have.

6. January 17, 1966 — The Palomares Incident occurred when an American B-52 bomber had a mid-air collision with its fuel supplier over Palomares, Spain. Both crashed and burned, but the bomber made a controlled jettison of its four 1.5 MT hydrogen bombs. Two parachuted safely to the ground. One’s chute failed and its fission nuclear ignition device exploded. However, the actual fusion nuclear reaction didn’t happen. The preliminary fission nuclear blast caused massive radioactive pollution. The attempted cleanup effort was enormous, and the site still radiates today. Searchers eventually recovered the fourth nuclear bomb from the sea after a long and expensive venture.

5. January 21, 1968 — Four 1.1 MT B23 thermonuclear hydrogen bombs were on board a U.S. B-52 when it caught fire near Thule AFB in Greenland. The situation was hopeless, so the crew set the plane on an autopilot descent towards the open ocean and then bailed out. Every crew member survived, but the bomber did something unexpected. With a mind of its own, it crash-landed itself on the Greenland ice causing the primary fission nuclear ignition material to explode. The main warheads didn’t follow suit. However, the radioactive contamination from the small nuke blasts caused an environmental nightmare for the Greenland area. One investigator said, “It was like four dirty bombs went off.”

4. August 29, 2007 — Although no damage was done, this is likely the most embarrassing nuclear accident the United States Air Force ever experienced. They lost six live AGM-129 ACM cruise missiles equipped with W80-1 variable-yield nuclear warheads for a 36-hour period. Yes, they lost them. The bombs got mistakenly loaded at Minot AFB in North Dakota for transport to Barksdale AFB in Louisiana.

These six thermonuclear hydrogen bombs were wrongly taken from a stockpile that were live rather than the decommissioned ones that were supposed to be the day’s cargo. The unguarded nukes sat on a runway all night and then arrived in Louisiana where the ground crew treated them like duds. This SNAFU caused heads to roll right up to the Secretary of Defense because of lax nuclear bomb safety policies.

3. October 03, 1986 — The Russians aren’t without their nuclear bomb accidents. However, they’re usually very tight-lipped so who knows how many they’ve had. This one was impossible to conceal as they rescued their sailors from the Russian K-219 nuclear-powered attack submarine. The sub was near Bermuda when a hatch cover failed. Water leaked in and mixed with nuclear-grade fuel which is not a good thing. Despite all efforts to save the ship, most of the crew was saved.

The submarine fared otherwise. It was put under tow by a Russian freight and taken towards the motherland. Once over very deep water in the mid-Atlantic, the sub broke free and went 18,000 feet to the bottom. With it were two nuclear reactors and 34 operational nuclear-tipped missiles. None of them have been recovered.

2. March 01, 1954 — Not all nuclear accidents come from near misses. This one came from a live and planned thermonuclear hydrogen bomb test the Americans pulled off at remote Bikini Atoll in the South Pacific. This was in nuclear bomb research infancy, and the United States military was going for the biggest and best bomb they could build. This day, they tested a project called Castle Bravo which engineers designed for a five MT yield. Somehow, they miscalculated.

The controlled blast was at least three times the expected force—somewhere between 15 and 20 MT. Observers placed outside the expected danger zone were radiated like they’d entered a blast furnace. Twenty-three pour souls on a Japanese fishing boat perished immediately with hundreds of native dwellers on nearby atolls consequently dying of radiation poisoning. Some were children who played in white fallout ash which they thought was this thing called snow.

The radioactive area was enormous. One analyst stated, “If ground zero had of been Washington, DC every resident in the greater Washington-Baltimore would have been instantly dead. Even in Philadelphia, 150 miles away, the majority of inhabitants would have died within an hour from radiation poisoning. In New York City, half the population would be dead by nightfall. And, all the way to the Canadian border inhabitants would be exposed to lethal radiation.”

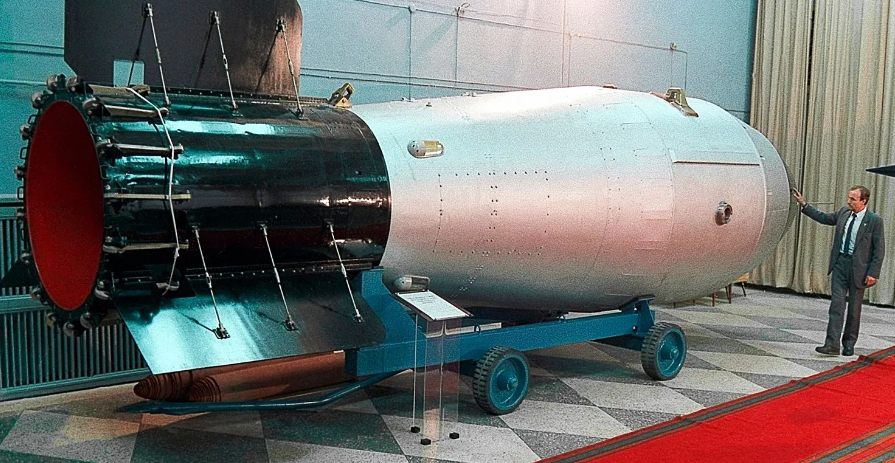

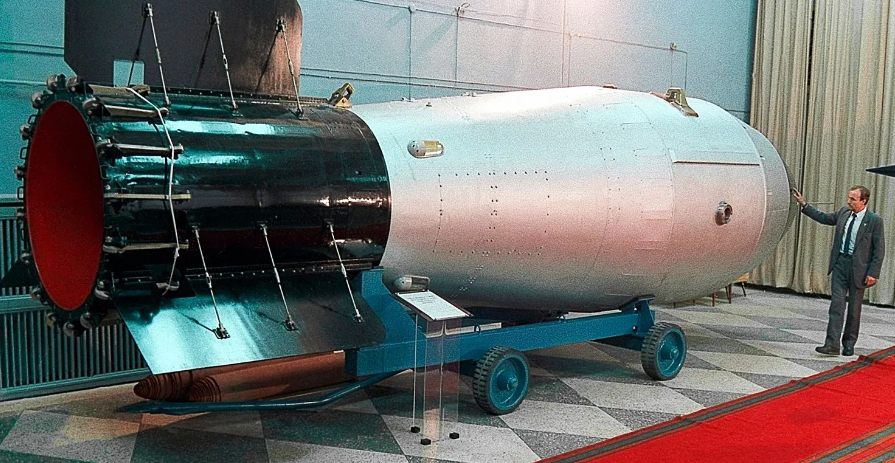

1. October 30, 1961— Leave it to the Russians to do something really big and radically brazen. They built a gigantic thermonuclear hydrogen bomb—a magnificently monstrous bomb. They called it Tsar Bomba but used the creative code-name Ivan. This was the most powerful nuclear weapon ever made. However, it doesn’t appear they intended Ivan to be this large.

Soviet RDS-202 Tsar Bomba was 26 feet long and 7 feet wide. Ivan’s static weight was 27 tons, and it needed a specially-modified Tu-95 bomber to carry it. The Russian crew detonated Ivan on a deserted island far in the barren north. The area was mostly uninhabited by Siberian terms which seemed like a good place for destructive nuclear testing.

The Russian military, being the secretive bunch they are, never declassified the intended design yield they built into Tsar Bomba. It certainly wasn’t the 57 MT thermonuclear explosion that ensued. This bang was so big that the flash was seen for 630 miles distant. The mushroom cloud extended 40 miles up and spread out hundreds of miles with radiation spreading over multi-thousands of square miles. Windows 560 miles away blew out from the concussion.

Western observers monitored the Tsar Bomba blast and confirmed the energy. They equated Tsar Bomba as using more energy than all the munitions expended by all sides during World War II. That included the nukes on Japan. There are no verified records of how much environmental damage Tsar Bomba accomplished or how many people perished in its aftermath.

The Future of Nuclear Weapon Accidents

It’s naïve to think the world will rid itself of nuclear weapons any time in the foreseeable future. The NPT countries continue to cooperate in reducing their nuclear inventories—within their parameters of trust. Many monitoring protocols keep participating countries “honest”, but it’s the non-NPT nuclear weapons possessors and the immediate proliferation countries that present a high risk for accidents—never mind using a nuke with intention.

Allowing irresponsible, belligerent countries like North Korea, Syria, and Iran to possess nuclear weapons is a serious mistake. It’s an unacceptable threat. It’s not just their instability in aggressively firing the first nuclear shot. It’s the chance they’ll make a terrible error and inadvertently activate a bomb.

The “responsible” nuclear community avoided intentional thermonuclear bomb-throwing since the lesson learned at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Plus the close call in Cuba. But they, too, still haven’t got the safety memo. As long as there’s human involvement with nuclear weapons, there’ll always be a potential accident.

It’s human nature to be careless with things like instruments of Armageddon. But, close calls with nuclear weapon accidents have terrible consequences. Just think of the innocent atoll kids who played in the snow.

Just when you think you’ve heard the lowest-of-the-low, along come these two judiciary scumbags who shipped helpless American children to jail in return for money kickbacks. This is no joke. Pennsylvania judges Mark Ciavarella and Michael Conahan received 28 years and 17 ½ years, respectively, in prison for what’s known as the Kids For Cash scandal. These two legal low-lives sentenced hundreds of defenseless children—some as young as eight—to jail time in a for-profit U.S. prison. The kids’ “crimes” included petty theft, smoking on school grounds, jaywalking, truancy, and other indiscretions.

Just when you think you’ve heard the lowest-of-the-low, along come these two judiciary scumbags who shipped helpless American children to jail in return for money kickbacks. This is no joke. Pennsylvania judges Mark Ciavarella and Michael Conahan received 28 years and 17 ½ years, respectively, in prison for what’s known as the Kids For Cash scandal. These two legal low-lives sentenced hundreds of defenseless children—some as young as eight—to jail time in a for-profit U.S. prison. The kids’ “crimes” included petty theft, smoking on school grounds, jaywalking, truancy, and other indiscretions. Between 2003 and 2008, Ciavarella and Conahan funnelled hundreds of children to the PA Child Care and the Western PA Child Care for-profit juvenile detention centers. In exchange, the two court crooks received and split $2.8 million in kickbacks. What they did with the money is a sick and shameful story of the seven sins.

Between 2003 and 2008, Ciavarella and Conahan funnelled hundreds of children to the PA Child Care and the Western PA Child Care for-profit juvenile detention centers. In exchange, the two court crooks received and split $2.8 million in kickbacks. What they did with the money is a sick and shameful story of the seven sins. That word came in April 2008 from a confidential source which triggered a multi-disciplinary investigation. The source originally implicated Conahan alone who was the initial focus of a complaint laid by the Philadelphia-based advocacy group called the Juvenile Law Centre. They petitioned the Pennsylvania Supreme Court to investigate Conahan which started the ball rolling.

That word came in April 2008 from a confidential source which triggered a multi-disciplinary investigation. The source originally implicated Conahan alone who was the initial focus of a complaint laid by the Philadelphia-based advocacy group called the Juvenile Law Centre. They petitioned the Pennsylvania Supreme Court to investigate Conahan which started the ball rolling. On August 11, 2011, Mark Ciavarella received a 28-year sentence. He’s serving it at a Kentucky federal prison and is set for release in 2035. Ciavarella will be 85 when he’s unlocked.

On August 11, 2011, Mark Ciavarella received a 28-year sentence. He’s serving it at a Kentucky federal prison and is set for release in 2035. Ciavarella will be 85 when he’s unlocked.