This is not a regular, bi-weekly Dyingwords post. It’s a special edition, and it’s an essay written by Paul Graham in October 2023 who shared it Farnam Street which is a critical thinking site I’ve followed for a long time. The topic is about superlinear returns, a concept of compounding growth. I feel it’s so important for long-term personal development to understand what superlinear returns are and how you can work this “magic” to your full advantage. Here’s Mr. Graham explaining superlinear returns.

This is not a regular, bi-weekly Dyingwords post. It’s a special edition, and it’s an essay written by Paul Graham in October 2023 who shared it Farnam Street which is a critical thinking site I’ve followed for a long time. The topic is about superlinear returns, a concept of compounding growth. I feel it’s so important for long-term personal development to understand what superlinear returns are and how you can work this “magic” to your full advantage. Here’s Mr. Graham explaining superlinear returns.

One of the most important things I didn’t understand about the world when I was a child is the degree to which the returns for performance are superlinear.

Teachers and coaches implicitly told us the returns were linear. “You get out,” I heard a thousand times, “what you put in.” They meant well, but this is rarely true. If your product is only half as good as your competitor’s, you don’t get half as many customers. You get no customers, and you go out of business.

It’s obviously true that the returns for performance are superlinear in business. Some think this is a flaw of capitalism, and that if we changed the rules it would stop being true. But superlinear returns for performance are a feature of the world, not an artifact of rules we’ve invented. We see the same pattern in fame, power, military victories, knowledge, and even benefit to humanity. In all of these, the rich get richer. [Note 1]

You can’t understand the world without understanding the concept of superlinear returns. And if you’re ambitious you definitely should, because this will be the wave you surf on.

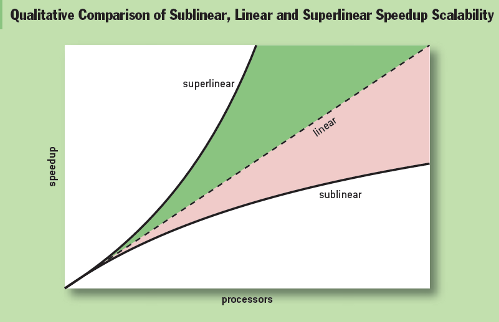

It may seem as if there are a lot of different situations with superlinear returns, but as far as I can tell they reduce to two fundamental causes: exponential growth and thresholds.

The most obvious case of superlinear returns is when you’re working on something that grows exponentially. For example, growing bacterial cultures. When they grow at all, they grow exponentially. But they’re tricky to grow. Which means the difference in outcome between someone who’s adept at it and someone who’s not is very great. Startups can also grow exponentially, and we see the same pattern there. Some manage to achieve high growth rates. Most don’t. And as a result you get qualitatively different outcomes: the companies with high growth rates tend to become immensely valuable, while the ones with lower growth rates may not even survive.

Y Combinator encourages founders to focus on growth rate rather than absolute numbers. It prevents them from being discouraged early on, when the absolute numbers are still low. It also helps them decide what to focus on: you can use growth rate as a compass to tell you how to evolve the company. But the main advantage is that by focusing on growth rate you tend to get something that grows exponentially.

YC doesn’t explicitly tell founders that with growth rate “you get out what you put in,” but it’s not far from the truth. And if growth rate were proportional to performance, then the reward for performance p over time t would be proportional to pt.

Even after decades of thinking about this, I find that sentence startling.

Whenever how well you do depends on how well you’ve done, you’ll get exponential growth. But neither our DNA nor our customs prepare us for it. No one finds exponential growth natural; every child is surprised, the first time they hear it, by the story of the man who asks the king for a single grain of rice the first day and double the amount each successive day.

What we don’t understand naturally we develop customs to deal with, but we don’t have many customs about exponential growth either, because there have been so few instances of it in human history. In principle herding should have been one: the more animals you had, the more offspring they’d have. But in practice grazing land was the limiting factor, and there was no plan for growing that exponentially.

Or more precisely, no generally applicable plan. There was a way to grow one’s territory exponentially: by conquest. The more territory you control, the more powerful your army becomes, and the easier it is to conquer new territory. This is why history is full of empires. But so few people created or ran empires that their experiences didn’t affect customs very much. The emperor was a remote and terrifying figure, not a source of lessons one could use in one’s own life.

The most common case of exponential growth in preindustrial times was probably scholarship. The more you know, the easier it is to learn new things. The result, then as now, was that some people were startlingly more knowledgeable than the rest about certain topics. But this didn’t affect customs much either. Although empires of ideas can overlap and there can thus be far more emperors, in preindustrial times this type of empire had little practical effect. [Note 2]

That has changed in the last few centuries. Now the emperors of ideas can design bombs that defeat the emperors of territory. But this phenomenon is still so new that we haven’t fully assimilated it. Few even of the participants realize they’re benefitting from exponential growth or ask what they can learn from other instances of it.

The other source of superlinear returns is embodied in the expression “winner take all.” In a sports match the relationship between performance and return is a step function: the winning team gets one win whether they do much better or just slightly better. [Note 3]

The source of the step function is not competition per se, however. It’s that there are thresholds in the outcome. You don’t need competition to get those. There can be thresholds in situations where you’re the only participant, like proving a theorem or hitting a target

It’s remarkable how often a situation with one source of superlinear returns also has the other. Crossing thresholds leads to exponential growth: the winning side in a battle usually suffers less damage, which makes them more likely to win in the future. And exponential growth helps you cross thresholds: in a market with network effects, a company that grows fast enough can shut out potential competitors.

Fame is an interesting example of a phenomenon that combines both sources of superlinear returns. Fame grows exponentially because existing fans bring you new ones. But the fundamental reason it’s so concentrated is thresholds: there’s only so much room on the A-list in the average person’s head.

The most important case combining both sources of superlinear returns may be learning. Knowledge grows exponentially, but there are also thresholds in it. Learning to ride a bicycle, for example. Some of these thresholds are akin to machine tools: once you learn to read, you’re able to learn anything else much faster. But the most important thresholds of all are those representing new discoveries. Knowledge seems to be fractal in the sense that if you push hard at the boundary of one area of knowledge, you sometimes discover a whole new field. And if you do, you get first crack at all the new discoveries to be made in it. Newton did this, and so did Durer and Darwin.

Are there general rules for finding situations with superlinear returns? The most obvious one is to seek work that compounds.

There are two ways work can compound. It can compound directly, in the sense that doing well in one cycle causes you to do better in the next. That happens for example when you’re building infrastructure, or growing an audience or brand. Or work can compound by teaching you, since learning compounds. This second case is an interesting one because you may feel you’re doing badly as it’s happening. You may be failing to achieve your immediate goal. But if you’re learning a lot, then you’re getting exponential growth nonetheless.

This is one reason Silicon Valley is so tolerant of failure. People in Silicon Valley aren’t blindly tolerant of failure. They’ll only continue to bet on you if you’re learning from your failures. But if you are, you are in fact a good bet: maybe your company didn’t grow the way you wanted, but you yourself have, and that should yield results eventually.

Indeed, the forms of exponential growth that don’t consist of learning are so often intermixed with it that we should probably treat this as the rule rather than the exception. Which yields another heuristic: always be learning. If you’re not learning, you’re probably not on a path that leads to superlinear returns.

But don’t overoptimize what you’re learning. Don’t limit yourself to learning things that are already known to be valuable. You’re learning; you don’t know for sure yet what’s going to be valuable, and if you’re too strict you’ll lop off the outliers.

What about step functions? Are there also useful heuristics of the form “seek thresholds” or “seek competition?” Here the situation is trickier. The existence of a threshold doesn’t guarantee the game will be worth playing. If you play a round of Russian roulette, you’ll be in a situation with a threshold, certainly, but in the best case you’re no better off. “Seek competition” is similarly useless; what if the prize isn’t worth competing for? Sufficiently fast exponential growth guarantees both the shape and magnitude of the return curve — because something that grows fast enough will grow big even if it’s trivially small at first — but thresholds only guarantee the shape. [Note 4]

A principle for taking advantage of thresholds has to include a test to ensure the game is worth playing. Here’s one that does: if you come across something that’s mediocre yet still popular, it could be a good idea to replace it. For example, if a company makes a product that people dislike yet still buy, then presumably they’d buy a better alternative if you made one. [Note 5]

It would be great if there were a way to find promising intellectual thresholds. Is there a way to tell which questions have whole new fields beyond them? I doubt we could ever predict this with certainty, but the prize is so valuable that it would be useful to have predictors that were even a little better than random, and there’s hope of finding those. We can to some degree predict when a research problem isn’t likely to lead to new discoveries: when it seems legit but boring. Whereas the kind that do lead to new discoveries tend to seem very mystifying, but perhaps unimportant. (If they were mystifying and obviously important, they’d be famous open questions with lots of people already working on them.) So one heuristic here is to be driven by curiosity rather than careerism — to give free rein to your curiosity instead of working on what you’re supposed to.

The prospect of superlinear returns for performance is an exciting one for the ambitious. And there’s good news in this department: this territory is expanding in both directions. There are more types of work in which you can get superlinear returns, and the returns themselves are growing.

There are two reasons for this, though they’re so closely intertwined that they’re more like one and a half: progress in technology, and the decreasing importance of organizations.

Fifty years ago it used to be much more necessary to be part of an organization to work on ambitious projects. It was the only way to get the resources you needed, the only way to have colleagues, and the only way to get distribution. So in 1970 your prestige was in most cases the prestige of the organization you belonged to. And prestige was an accurate predictor, because if you weren’t part of an organization, you weren’t likely to achieve much. There were a handful of exceptions, most notably artists and writers, who worked alone using inexpensive tools and had their own brands. But even they were at the mercy of organizations for reaching audiences. [Note 6]

A world dominated by organizations damped variation in the returns for performance. But this world has eroded significantly just in my lifetime. Now a lot more people can have the freedom that artists and writers had in the 20th century. There are lots of ambitious projects that don’t require much initial funding, and lots of new ways to learn, make money, find colleagues, and reach audiences.

There’s still plenty of the old world left, but the rate of change has been dramatic by historical standards. Especially considering what’s at stake. It’s hard to imagine a more fundamental change than one in the returns for performance.

Without the damping effect of institutions, there will be more variation in outcomes. Which doesn’t imply everyone will be better off: people who do well will do even better, but those who do badly will do worse. That’s an important point to bear in mind. Exposing oneself to superlinear returns is not for everyone. Most people will be better off as part of the pool. So who should shoot for superlinear returns? Ambitious people of two types: those who know they’re so good that they’ll be net ahead in a world with higher variation, and those, particularly the young, who can afford to risk trying it to find out. [Note 7]

The switch away from institutions won’t simply be an exodus of their current inhabitants. Many of the new winners will be people they’d never have let in. So the resulting democratization of opportunity will be both greater and more authentic than any tame intramural version the institutions themselves might have cooked up. Not everyone is happy about this great unlocking of ambition. It threatens some vested interests and contradicts some ideologies. [Note 8]

But if you’re an ambitious individual it’s good news for you. How should you take advantage of it?

The most obvious way to take advantage of superlinear returns for performance is by doing exceptionally good work. At the far end of the curve, incremental effort is a bargain. All the more so because there’s less competition at the far end — and not just for the obvious reason that it’s hard to do something exceptionally well, but also because people find the prospect so intimidating that few even try. Which means it’s not just a bargain to do exceptional work, but a bargain even to try to.

There are many variables that affect how good your work is, and if you want to be an outlier you need to get nearly all of them right. For example, to do something exceptionally well, you have to be interested in it. Mere diligence is not enough. So in a world with superlinear returns, it’s even more valuable to know what you’re interested in, and to find ways to work on it. [Note 9]

It will also be important to choose work that suits your circumstances. For example, if there’s a kind of work that inherently requires a huge expenditure of time and energy, it will be increasingly valuable to do it when you’re young and don’t yet have children.

There’s a surprising amount of technique to doing great work. It’s not just a matter of trying hard. I’m going to take a shot giving a recipe in one paragraph.

Choose work you have a natural aptitude for and a deep interest in. Develop a habit of working on your own projects; it doesn’t matter what they are so long as you find them excitingly ambitious. Work as hard as you can without burning out, and this will eventually bring you to one of the frontiers of knowledge. These look smooth from a distance, but up close they’re full of gaps. Notice and explore such gaps, and if you’re lucky one will expand into a whole new field. Take as much risk as you can afford; if you’re not failing occasionally you’re probably being too conservative. Seek out the best colleagues. Develop good taste and learn from the best examples. Be honest, especially with yourself. Exercise and eat and sleep well and avoid the more dangerous drugs. When in doubt, follow your curiosity. It never lies, and it knows more than you do about what’s worth paying attention to. [Note10]

And there is of course one other thing you need: to be lucky. Luck is always a factor, but it’s even more of a factor when you’re working on your own rather than as part of an organization. And though there are some valid aphorisms about luck being where preparedness meets opportunity and so on, there’s also a component of true chance that you can’t do anything about. The solution is to take multiple shots. Which is another reason to start taking risks early.

The best example of a field with superlinear returns is probably science. It has exponential growth, in the form of learning, combined with thresholds at the extreme edge of performance — literally at the limits of knowledge.

The result has been a level of inequality in scientific discovery that makes the wealth inequality of even the most stratified societies seem mild by comparison. Newton’s discoveries were arguably greater than all his contemporaries’ combined. [Note 11]

This point may seem obvious, but it might be just as well to spell it out. Superlinear returns imply inequality. The steeper the return curve, the greater the variation in outcomes.

In fact, the correlation between superlinear returns and inequality is so strong that it yields another heuristic for finding work of this type: look for fields where a few big winners outperform everyone else. A kind of work where everyone does about the same is unlikely to be one with superlinear returns.

What are fields where a few big winners outperform everyone else? Here are some obvious ones: sports, politics, art, music, acting, directing, writing, math, science, starting companies, and investing. In sports the phenomenon is due to externally imposed thresholds; you only need to be a few percent faster to win every race. In politics, power grows much as it did in the days of emperors. And in some of the other fields (including politics) success is driven largely by fame, which has its own source of superlinear growth. But when we exclude sports and politics and the effects of fame, a remarkable pattern emerges: the remaining list is exactly the same as the list of fields where you have to be independent-minded to succeed — where your ideas have to be not just correct, but novel as well. [Note 12]

This is obviously the case in science. You can’t publish papers saying things that other people have already said. But it’s just as true in investing, for example. It’s only useful to believe that a company will do well if most other investors don’t; if everyone else thinks the company will do well, then its stock price will already reflect that, and there’s no room to make money.

What else can we learn from these fields? In all of them you have to put in the initial effort. Superlinear returns seem small at first. At this rate, you find yourself thinking, I’ll never get anywhere. But because the reward curve rises so steeply at the far end, it’s worth taking extraordinary measures to get there.

In the startup world, the name for this principle is “do things that don’t scale.” If you pay a ridiculous amount of attention to your tiny initial set of customers, ideally you’ll kick off exponential growth by word of mouth. But this same principle applies to anything that grows exponentially. Learning, for example. When you first start learning something, you feel lost. But it’s worth making the initial effort to get a toehold, because the more you learn, the easier it will get.

There’s another more subtle lesson in the list of fields with superlinear returns: not to equate work with a job. For most of the 20th century the two were identical for nearly everyone, and as a result we’ve inherited a custom that equates productivity with having a job. Even now to most people the phrase “your work” means their job. But to a writer or artist or scientist it means whatever they’re currently studying or creating. For someone like that, their work is something they carry with them from job to job, if they have jobs at all. It may be done for an employer, but it’s part of their portfolio.

It’s an intimidating prospect to enter a field where a few big winners outperform everyone else. Some people do this deliberately, but you don’t need to. If you have sufficient natural ability and you follow your curiosity sufficiently far, you’ll end up in one. Your curiosity won’t let you be interested in boring questions, and interesting questions tend to create fields with superlinear returns if they’re not already part of one.

The territory of superlinear returns is by no means static. Indeed, the most extreme returns come from expanding it. So while both ambition and curiosity can get you into this territory, curiosity may be the more powerful of the two. Ambition tends to make you climb existing peaks, but if you stick close enough to an interesting enough question, it may grow into a mountain beneath you.

Notes

There’s a limit to how sharply you can distinguish between effort, performance, and return, because they’re not sharply distinguished in fact. What counts as return to one person might be performance to another. But though the borders of these concepts are blurry, they’re not meaningless. I’ve tried to write about them as precisely as I could without crossing into error.

[1] Evolution itself is probably the most pervasive example of superlinear returns for performance. But this is hard for us to empathize with because we’re not the recipients; we’re the returns.

[2] Knowledge did of course have a practical effect before the Industrial Revolution. The development of agriculture changed human life completely. But this kind of change was the result of broad, gradual improvements in technique, not the discoveries of a few exceptionally learned people.

[3] It’s not mathematically correct to describe a step function as superlinear, but a step function starting from zero works like a superlinear function when it describes the reward curve for effort by a rational actor. If it starts at zero then the part before the step is below any linearly increasing return, and the part after the step must be above the necessary return at that point or no one would bother.

[4] Seeking competition could be a good heuristic in the sense that some people find it motivating. It’s also somewhat of a guide to promising problems, because it’s a sign that other people find them promising. But it’s a very imperfect sign: often there’s a clamoring crowd chasing some problem, and they all end up being trumped by someone quietly working on another one.

[5] Not always, though. You have to be careful with this rule. When something is popular despite being mediocre, there’s often a hidden reason why. Perhaps monopoly or regulation make it hard to compete. Perhaps customers have bad taste or have broken procedures for deciding what to buy. There are huge swathes of mediocre things that exist for such reasons.

[6] In my twenties I wanted to be an artist and even went to art school to study painting. Mostly because I liked art, but a nontrivial part of my motivation came from the fact that artists seemed least at the mercy of organizations.

[7] In principle everyone is getting superlinear returns. Learning compounds, and everyone learns in the course of their life. But in practice few push this kind of everyday learning to the point where the return curve gets really steep.

[8] It’s unclear exactly what advocates of “equity” mean by it. They seem to disagree among themselves. But whatever they mean is probably at odds with a world in which institutions have less power to control outcomes, and a handful of outliers do much better than everyone else. It may seem like bad luck for this concept that it arose at just the moment when the world was shifting in the opposite direction, but I don’t think this was a coincidence. I think one reason it arose now is because its adherents feel threatened by rapidly increasing variation in performance.

[9] Corollary: Parents who pressure their kids to work on something prestigious, like medicine, even though they have no interest in it, will be hosing them even more than they have in the past.

[10] The original version of this paragraph was the first draft of “How to Do Great Work.” As soon as I wrote it I realized it was a more important topic than superlinear returns, so I paused the present essay to expand this paragraph into its own. Practically nothing remains of the original version, because after I finished “How to Do Great Work” I rewrote it based on that.

[11] Before the Industrial Revolution, people who got rich usually did it like emperors: capturing some resource made them more powerful and enabled them to capture more. Now it can be done like a scientist, by discovering or building something uniquely valuable. Most people who get rich use a mix of the old and the new ways, but in the most advanced economies the ratio has shifted dramatically toward discovery just in the last half century.

[12] It’s not surprising that conventional-minded people would dislike inequality if independent-mindedness is one of the biggest drivers of it. But it’s not simply that they don’t want anyone to have what they can’t. The conventional-minded literally can’t imagine what it’s like to have novel ideas. So the whole phenomenon of great variation in performance seems unnatural to them, and when they encounter it they assume it must be due to cheating or to some malign external influence.

(With due credit and sincere appreciation to Paul Graham. His original essay can be read here.)