Amelia Earhart’s disappearance isn’t just one of aviation’s great unsolved mysteries—her vanish is one of modern history’s enduring human interest puzzles. Earhart was at her peak of fame, attempting the first around-the-world flight, when she and her twin-engine Lockheed 10E Electra went missing over the vast equatorial Pacific on July 2, 1937. Despite an extensive search and endless speculation, no conclusive or “smoking gun” evidence proves what really happened to Amelia Earhart.

Amelia Earhart’s disappearance isn’t just one of aviation’s great unsolved mysteries—her vanish is one of modern history’s enduring human interest puzzles. Earhart was at her peak of fame, attempting the first around-the-world flight, when she and her twin-engine Lockheed 10E Electra went missing over the vast equatorial Pacific on July 2, 1937. Despite an extensive search and endless speculation, no conclusive or “smoking gun” evidence proves what really happened to Amelia Earhart.

Or… does it?

A 2018 paper published in Forensic Anthropology using modern Fordisc computerized forensic osteology and biometric science concludes with over 99% certainty that historical human bones found in 1940 on tiny uninhabited Nikumaroro Island in the Republic of Kiribati are, in fact, Amelia Earhart’s. It concludes Earhart crash-landed on this volcanic atoll after being off course, disoriented and low on fuel. Then, Amelia Earhart perished as a thirst-desperate castaway, chased down and eaten by aggressive hordes of giant coconut crabs—quite possibly while she was still alive.

Amelia Earhart was a woman ahead of her time in every way. Not only was she the sixteenth licensed female pilot in America, she was the first woman to solo-cross the Atlantic. Earhart was a savvy aviator, businesswoman and social celebrity. Her talents extended to being a fashion design icon and an early feminine activist. She also married wealthy book publisher George Putnam. This gave Earhart the capital and connections to fund her expensive aviation ventures.

Amelia Earhart was a woman ahead of her time in every way. Not only was she the sixteenth licensed female pilot in America, she was the first woman to solo-cross the Atlantic. Earhart was a savvy aviator, businesswoman and social celebrity. Her talents extended to being a fashion design icon and an early feminine activist. She also married wealthy book publisher George Putnam. This gave Earhart the capital and connections to fund her expensive aviation ventures.

Planning the First Around-The-World Solo Flight

At 40, Amelia Earhart had considerable flight time in different aircraft types. She was a competent aviator for having no military flight training, but had a tremendous self-confidence and a burning desire to exceed limitations. Some criticized Earhart for recklessly pushing the safety envelope, particularly because she had limited navigation and radio communication skills.

That didn’t prevent Amelia Earhart from setting aviation records. Although she was planning the first “solo” circumequitorial flight, she wasn’t actually doing this alone. Earhart intended to remain in the left seat which is reserved for the captain in command. However, she flew with a right-hand navigator who was also a highly-accomplished pilot. This was Fred Noonan who was a key figure in Earhart’s overall flight team. Other members consisted of engineers, mechanics, coordinators and media relations staff.

That didn’t prevent Amelia Earhart from setting aviation records. Although she was planning the first “solo” circumequitorial flight, she wasn’t actually doing this alone. Earhart intended to remain in the left seat which is reserved for the captain in command. However, she flew with a right-hand navigator who was also a highly-accomplished pilot. This was Fred Noonan who was a key figure in Earhart’s overall flight team. Other members consisted of engineers, mechanics, coordinators and media relations staff.

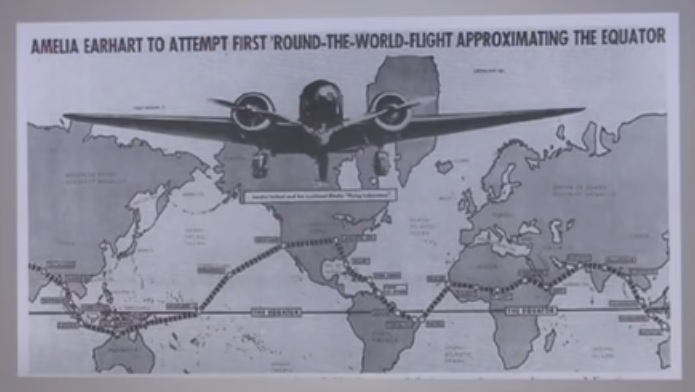

Amelia Earhart’s first plan to solo the equator started in Oakland, California on March 17, 1937 and headed westward toward Hawaii. After refueling at the US Navy Field at Pearl Harbor, Earhart took off for remote Howland Island located half-way between Hawaii and Lae in New Guinea. She never made it off the ground. Something went wrong while powering down the runway, and Earhart lost control with the Electra going into a sideways loop. The starboard, or right front, landing gear snapped off and the plane veered on its side with the right engine prop peeling the pavement.

Earhart’s Electra was severely damaged. The plane was salvaged, loaded onto a ship and sent back to the States for repair. It was modified for extra fuel tanks and special aluminum covers over fuselage Plexiglass windows. Also added was a 25-foot trailing antenna for finding directional radio frequency (DRF) signals.

Changing prevailing weather patterns forced Amelia Earhart’s second around-the-world attempt to change directions. Instead of an east to west approach, they elected to follow favorable season winds flowing from west to east. Earhart departed Miami on June 1, 1937 and hopped across South America, Africa, India and Southeast Asia. On June 29, Earhart landed at Lae, New Guinea in the eastern South Pacific. Noonan was with her throughout.

During the 28-day series, Earhart and Noonan traveled 22,000 miles without issues. However, the next leg from Lae to the Howland Island refill and rest stop was the longest yet. Howland was 2,556 miles east and an estimated flight time of 19 hours.

During the 28-day series, Earhart and Noonan traveled 22,000 miles without issues. However, the next leg from Lae to the Howland Island refill and rest stop was the longest yet. Howland was 2,556 miles east and an estimated flight time of 19 hours.

Earhart’s Electra left Lae at 00:00 GMT on July 2, 1937. It carried 1090 gallons of high-octane aviation fuel which was 70 gallons less than full capacity. Her engineering crew was confident Earhart had sufficient fuel for extra time and that her fuel/weight ratio was just right to give the Electra maximum distance performance. They allowed for course alteration time as well as slight navigation error.

The Fateful Flight’s Disappearance

Before leaving Lae, Earhart ran through all her airplane systems. All checked in order except for her directional finding antenna. She dismissed this as being too close to the sending signal at the aerodrome and proceeded on without any physical inspection. From Fred Noonan’s point as a navigator, the DRF antenna didn’t matter. He was trained in conventional navigation including maps, compass, landmarks and celestial navigation with his trusty Brandis-made marine sexton. Radio navigation was in its infancy and Noonan wasn’t experienced in it.

Before leaving Lae, Earhart ran through all her airplane systems. All checked in order except for her directional finding antenna. She dismissed this as being too close to the sending signal at the aerodrome and proceeded on without any physical inspection. From Fred Noonan’s point as a navigator, the DRF antenna didn’t matter. He was trained in conventional navigation including maps, compass, landmarks and celestial navigation with his trusty Brandis-made marine sexton. Radio navigation was in its infancy and Noonan wasn’t experienced in it.

Part of the Lae to Howland Island navigation contingency was the US Coast Guard cutter Itasca being moored at Howland Island where it monitored radio voice signals. The Itasca prepared to send visual smoke stack signals to the Electra once they knew it was in range. Communications included transmissions on the long 6210 kHz daytime frequency and the shorter 3105 kHz nighttime frequency. Neither Earhart nor Noonan knew Morse Code. That was the standard aeronautical communication pre-WW2. They exclusively relied on English voice transmissions on these specifically designated frequencies.

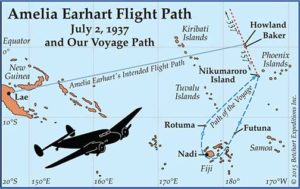

Noonan’s navigational plan was to fly by compass bearing while monitoring time and ground speed indication. He had a fix on Howland Island and the route crossed the equator on a shallow south-north angle. Along with this, Noonan computed a time-distance chart. At night, he’d planned to use celestial verification with his sexton should the skies be clear.

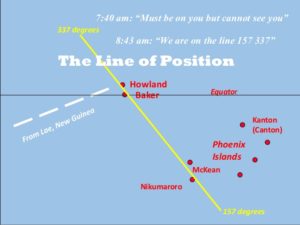

Ultimately, Noonan’s navigation plan had a “fail-safe” back-up come sunrise. He intended to establish an event horizon plane from the breaking sun that ran from 157 compass degrees to 337 degrees. Once achieving this directional line, it seemed a simple matter to fly back and forth along it a north-northwest to south-southeast pattern and visually find Howland Island. The plan included getting guided radio messages from the Itasca and seeing its bellowing black smoke.

Ultimately, Noonan’s navigation plan had a “fail-safe” back-up come sunrise. He intended to establish an event horizon plane from the breaking sun that ran from 157 compass degrees to 337 degrees. Once achieving this directional line, it seemed a simple matter to fly back and forth along it a north-northwest to south-southeast pattern and visually find Howland Island. The plan included getting guided radio messages from the Itasca and seeing its bellowing black smoke.

Earhart remained at the controls and on the radio at all times, ensuring she’d be recognized as the sole pilot. The Electra contained a modified Western Electric model 20B transmitter/receiver and used the call sign KHAQQ. She regularly checked-in with Lae at planned one-hour intervals, reporting position and conditions. Eventually, Earhart was out of Lae’s range and flying toward Howland Island where the Itasca waited to receive hourly transmissions. This is where communication breakdown began and Earhart’s path to disaster was sealed.

In 1937, ships and planes were not particularly compatible. That’s with exception of the military who were advancing in aircraft carrier technology. It wasn’t so with the Coast Guard where the cutter Itasca only had the ability to monitor Earhart’s frequencies. They weren’t able to transmit on 3105 and 6210. However, Earhart didn’t know that. She and Fred Noonan expected replies to her messages once approaching Howland, getting voice direction from the ship.

Itasca’s radio log clearly recorded numerous transmissions from Earhart. The first important call was at 7:42 am Howland local time on July 2, 1937. (Earhart crossed the International Date Line and the day reverted back to July 2). She broadcast on 3105, “We must be on you but cannot see you. Gas is running low. Been unable to reach you by radio. We are flying at 1,000 feet.” The Itasca recorded another Earhart message at 8:43 am stating, “We are on the line 157/337. We repeat this message on 6210 kilocycles.”

That was the last “official” voice transmission from Amelia Earhart. But, it certainly wasn’t the last signal from Earhart’s Electra. For the next five days, at least 57 credible radio receiving sources reported signals on 3105 and 6210 kHz.

Those channels were specifically reserved for Amelia Earhart’s around-the-world flight. All other radio users stayed on other channels. Some of those apparently credible sources recorded Amelia Earhart stating her name, her state of peril and describing her marooned location.

Searching for Amelia Earhart

The Itasca crew expected Earhart to land on Howland Island around 8:30 am local time. They also knew she’d allowed an extra hour’s flying time in case of headwinds or course alterations. The 8:43 message advising Earhart was on the 157/337 line was entirely normal. The Itasca wasn’t concerned about her not being able to hear the ship’s voice broadcasts. It wasn’t until several hours after the last transmission and well past the estimated fuel supply end that concern started.

Immediately, search efforts were uncoordinated and ineffective. There was no contingency plan for a search and rescue effort, and the Coast Guard cutter was the only vessel in the vicinity. Because the Itasca no longer received radio messages from Earhart, they made the worst-case assumption that she’d ditched at sea after running out of fuel—likely sinking.

Immediately, search efforts were uncoordinated and ineffective. There was no contingency plan for a search and rescue effort, and the Coast Guard cutter was the only vessel in the vicinity. Because the Itasca no longer received radio messages from Earhart, they made the worst-case assumption that she’d ditched at sea after running out of fuel—likely sinking.

The Itasca notified the US Navy, then began a best-guess surface search north and west of Howland along the 157/337 line dissecting Howland Island. There were no aircraft available at Howland and the US Navy’s nearest plane-equipped ship was the battleship Colorado that had flying boat auxiliaries. It was three days before the Colorado was close enough to start aerial searches and five days before the carrier USS Lexington joined in.

Most search efforts focused on the 157/337 line to the northwest and southeast within a 100-mile radius—thinking was that Earhart reported “must be on you” and she was flying the line. Naturally, this made the most sense to search this grid. The question was how far along that line she truly intersected it.

By July 10, a Catalina flying boat from the Colorado expanded the 157/337 line out to 350 miles south-southeast of Howland Island and flew over a tiny atoll called Gardner Island. It perfectly dissected Earhart’s navigation line but was far, far off course. Gardner is now known by its Polynesian name Nikumaroro.

Search logs record the Catalina crew saw “clear signs of recent human habitation” on Nikumaroro. Exactly what these signs wasn’t documented, although Nikumaroro hadn’t been populated since the 1880s. However, searchers didn’t see any evidence of a downed airplane. Nor did they see anyone stranded and waving on the beach. After ten minutes and several circles around the two-mile long atoll that enveloped an interior lagoon, the Catalina left and wrote off Nikumaroro as a possible spot holding what remained of Amelia Earhart.

Amelia Earhart’s search ended on July 19. 1937. Most of the search time and effort focused on the 100-mile radius of Howland Island and tightly along the 137/337 diagonal compass line. Not a trace of her Electra or its contents was seen. Not an oil slick. Not a tire. Not a life raft. Not a floating seat cushion or a wooden sexton box. Nothing. Amelia Earhart was officially declared dead by a Los Angeles court and the official investigation concluded.

Amelia Earhart’s Radio Transmissions

There’s overwhelming information indicating Amelia Earhart continued sending radio transmissions for six days after disappearing from the air. This comes from a credible collection of sources including aviation radio professionals, amateur HAM radio operators and astute civilians glued to their shortwave radio receivers.

Pan Am Airlines maintained radio transmission posts across the Pacific to guide their expanding airline fleet making trips from continental America to Australia and Southeast Asia. These posts had state-of-the-art equipment depending on DRF technology to help civilian airlines navigate the wide-open Pacific. As well, the US military expanded their LORAN navigational system—its core principle being directional radio beam functions.

Pan Am Airlines maintained radio transmission posts across the Pacific to guide their expanding airline fleet making trips from continental America to Australia and Southeast Asia. These posts had state-of-the-art equipment depending on DRF technology to help civilian airlines navigate the wide-open Pacific. As well, the US military expanded their LORAN navigational system—its core principle being directional radio beam functions.

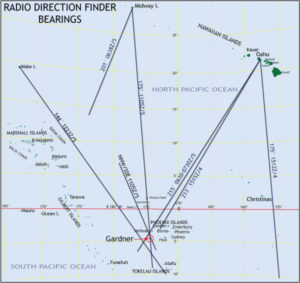

Pan Am stations in Oahu, Midway and Wake Islands all recorded radio beam transmissions on the 3105/6210 frequencies during the first six days after Earhart disappeared. These advanced stations had the ability to find beam location angle directions. Using each station’s source angles and applying simple triangulation, it’s shockingly obvious that all lines intersected on Nikumaroro or what was then called Gardner Island.

Someone on Nikumaroro (Gardner) was broadcasting on Earhart’s channels from July 2 to July 8, 1937. That’s clear. But what’s not clear is why authorities didn’t clue into this and share the information. The answer simply defaults to an immensely remote location and a lack of coordination.

Earhart’s record-setting flight was a private publicity stunt. It wasn’t a public-sponsored or military authorized operation. As such, there was no pre-planned contingency or even a will to properly investigate and coordinate incoming tips and drips of information. Although each small information point was well-meaning and probably accurate, these bits slipped through the cracks as the clock ticked. That included the credible tips about Earhart’s distress calls.

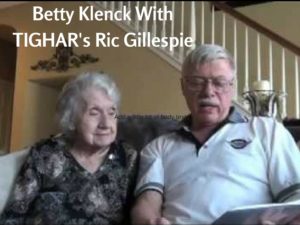

Betty Klenck’s Notebook

Teenager Betty Klenck of St. Petersburg, Florida was one of ten civilians hearing Amelia Earhart’s desperate radio pleas for help. On July 2, 1937 Betty tuned to her family’s shortwave radio listening for new songs and writing down lyrics so she could compose her own art. Over a one and three-quarter period, Betty heard Amelia Earhart calling for help and copied bits of Earhart’s messages in her notebook.

Teenager Betty Klenck of St. Petersburg, Florida was one of ten civilians hearing Amelia Earhart’s desperate radio pleas for help. On July 2, 1937 Betty tuned to her family’s shortwave radio listening for new songs and writing down lyrics so she could compose her own art. Over a one and three-quarter period, Betty heard Amelia Earhart calling for help and copied bits of Earhart’s messages in her notebook.

Immediately, you’d wonder how an American teen being thousands of miles from Nikumaroro could possibly hear Earhart’s radio distress calls when the Itasca—only a few hundred miles away—couldn’t. The reason is hyperbolic wave skip. Shortwave frequencies like 3105 will bounce off the ionosphere and hit random places like Betty’s Florida set.

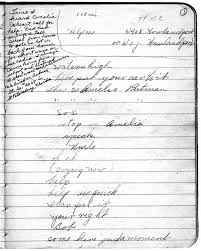

It’s not just that Betty Klenck recorded Earhart’s calls that are convincing. It’s what the messages said. Betty would have no way of knowing what the Earhart circumstances were, except she recognized the Earhart name and recorded live-time while Earhart broadcasted. Here are some of Betty’s notes:

This is Amelia Earhart

This is Amelia Earhart- This is Amelia Putnam

- SOS

- 58 338

- Send us help

- Water rising

- New York City

- NYC NYC

- NY NY NY

Betty Klenck reported she heard what appeared to be a desperate plea from a woman with an injured man in the background. The man seemed trying to get to the microphone, but the female broadcaster struggled with him, maintaining control. Betty included her father in listening which corroborated her information’s credibility.

Five things support Betty Klenck’s credibility:

- She wrote in her notebook within other intermittent radio events.

- She used SOS/Send Us Help with Amelia Earhart’s name.

- She recorded coordinates 58/338.

- She noted water rising.

- She repeatedly referred to New York City.

On their own, each point might seem mute or even fabricated by an enthusiastic Earhart girl-fan overwhelmed by media reporting a celebrity’s peril. That’s not the case here. Betty recorded this information before Earhart’s disappearance was public knowledge.

Betty would have no idea what 58/338 meant. It’s slightly off the 157/337 line but so close that it can’t be a coincidence. Earhart was relaying this, probably with compass correction. These were true compass lines for a particular point on Nikumaroro.

Betty recorded “water rising”. This seems irrelevant. Yet, years later, the investigation revealed just how important rising tides were on impacting Earhart’s radio transmission times.

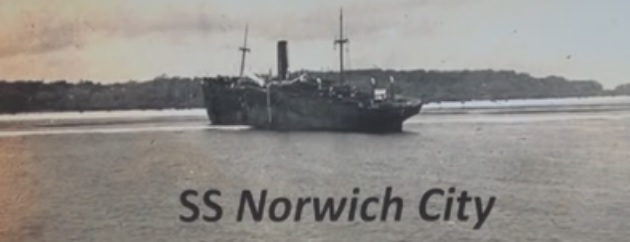

New York City? NYC? This is as close to the “smoking gun” in Earhart’s circumstantial evidence as you can get. Moving ahead, the suspected Nikumaroro crash site was beside the historical “Norwich City” shipwreck stuck on the only level landing reef on Nikumaroro. Earhart transmitted a known Nikumaroro landmark to help find her. Betty Klenck said Earhart stated “New York City” or something similar so many times that she used the abbreviation NY/NYC rather than writing it in full.

The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery

Credit for properly investigating Amelia Earhart’s disappearance goes to a private interest group called The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR). This dedicated bunch of civilian aviation sleuths has done an amazing job over 25 years. They’ve put together an Amelia Earhart file envious of any government, police or public forensic agency.

Ric Gillespie is TIGHAR’s articulate spokesperson. He’s also the leading influence in organizing a dozen TIGHAR expeditions to Nikumaroro Island. During these trips, TIGHAR volunteers uncovered some convincing physical and circumstantial evidence that Earhart’s Electra landed at low tide on a rocky reef and that she remained alive for some time. Here’s what TIGHAR identified from their investigations and excavations.

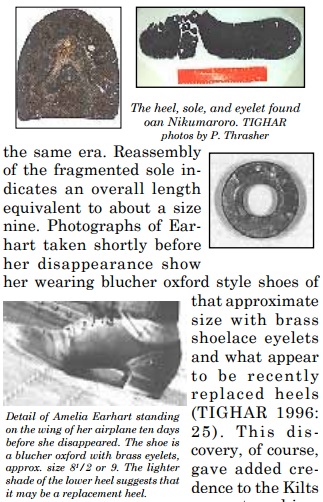

- A Shoe Sole. This was positively identified as being a resole from a woman’s size 8 1/2 or 9 American-made Cats Paw Biltrite brand popular in the 1930s. The remnant also contained part of the metatarsal cover showing a brass shoelace eyelet. Researchers sourced known photos from Earhart’s 1937 venture that shows her wearing identical Blucher Oxford style re-soled shoes with those eyelets.

- A Sextant Box. This wooden box was recorded in 1940 nearby where the original bones suspected to be Earhart’s were found at a location now called Seven Site on Nikumaroro. The black metal sextant was gone but the box bore the numbers 3500 in stencil and 1542 hand-printed in ink. TIGHAR researchers identified the number 3500 as being from the American Brandis sextant brand and the number 1542 as being a particular American Naval Observatory. This brand and numbering is entirely consistent with the sextant belonging to Fred Noonan.

- A Jar of “Dr. Berry’s Freckle Ointment”. It’s well recorded that Amelia Earhart had a freckled complexion and was self-conscious about it. She carried this product as part of her make-up kit which was an important part of her public appearance preparation. Researchers surmise Earhart might have salvaged the skin cream to use as a sunblock, protecting her light, reddish-toned shin from powerful sun rays at the equator.

- A Woman’s Compact, Dried Makeup and Mirror. Earhart also carried these items as part of her personal hygiene effects. She may have used them as a sunblock, too. The mirror may have served as an emergency signaling device.

- A Benedictine Bottle. Earhart was fond of the social liquor Benedictine and had a supply on the Electra. The Nikumaroro bottle had the neck broken off, allowing it to have a larger scooping capacity. Researchers surmise it may have been modified as a water collection device.

- Plexiglass and Aluminum Pieces. Two physical artifacts possibly associated with Earhart’s Electra were found on Nikumaroro. Both were oblong and 19 inches by 23 inches, entirely consistent with window covers made when the Electra was outfitted with long-range fuel tanks. The metal and plastic parts were the same material, thickness and shape as the window patches. Rivet holes were also consistent with those designed for the Electra’s modification.

- Clam Shells, Fish and Bird Bones and a Cooking Fire. TIGHAR researchers identified Seven Site as having clear signs of temporary human occupation that is not consistent with a historical Polynesian native settlement. Charcoal residue and organic life evidence consistent with lagoon creatures showed someone had camped at Seven Site for possibly a week. Researchers assessed every potential campsite on Nikumaroro and determined Seven Site was the most logical place for a castaway to stay. The site’s name comes from the shape of a seven.

The Bevington Photograph

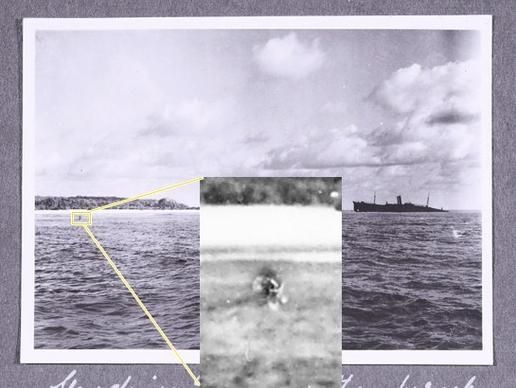

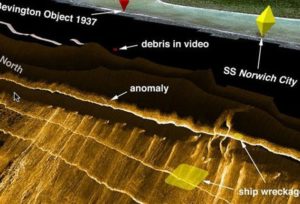

TIGHAR researchers place a lot of weight on what’s known as the Bevington Photograph. It’s a historic photo taken in October, 1937 (three months after Earhart disappeared) by British Colonial Service officer Eric Bevington. He was part of a British survey party who arrived at Nikumaroro to scout Loran navigation sites as part of the Pacific expansion.

Bevington took a snap of the long, flat tidal reef where the Norwich City wreck lay stranded. In the left side of the photograph, some foreign dark object extends from the water surface. It appears no flaw in the photo, rather Bevington captured the image of what could be the tire and broken landing strut of Earhart’s Electra.

TIGHAR researchers located the original Bevington photograph in British archives. They contracted credible forensic photography experts to review and enhance the picture. Without question, the Bevington photo is authentic and not altered in any way. Digital enhancements support that the object is man-made and consistent with an Electra’s landing gear.

Researchers also identified an eyewitness to the original object in the water. Emily Sikuli was a little Fijian girl who lived on Nikumaroro in the 1940s while the island was a commercial coconut farm. Sikuli stated her father pointed out aircraft wreckage on the reef near the Norwich City wreck and speculated it came from Earhart’s lost plane. Sikuli’s placement of the aircraft parts is precisely where the object in the Bevington photo sits.

Researchers also identified an eyewitness to the original object in the water. Emily Sikuli was a little Fijian girl who lived on Nikumaroro in the 1940s while the island was a commercial coconut farm. Sikuli stated her father pointed out aircraft wreckage on the reef near the Norwich City wreck and speculated it came from Earhart’s lost plane. Sikuli’s placement of the aircraft parts is precisely where the object in the Bevington photo sits.

It’s important to consider what’s known about a Lockheed 10E Electra crash landing. When Earhart originally crashed on takeoff in Hawaii on her first trans-world flight attempt, the starboard or right side landing strut and tire snapped off. This was a common Achilles Heel flaw with the Electra which has a tail-dragging tricycle landing system.

Making an assumption that the Electra’s left or port landing gear stayed intact if Earhart crashed on Nikumaroro’s low tide reef, then the plane would stay semi-upright with the port engine and propeller being clear from the ground and low-tide waterline. This is a highly-important conjecture given what TIGHAR researchers found out about how Earhart’s suspected radio transmissions interacted with known tide times during the first week of July in 1937.

TIGHAR Tide and Transmission Analysis

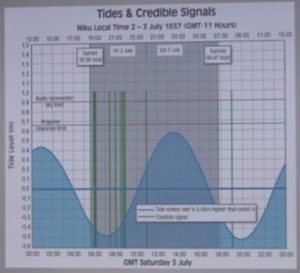

The TIGHAR organization attracts some of the world’s most experienced and enthusiastic aviators. TIGHAR also attracts some of the most analytical aeronautic technicians who should have been detectives and professional forensic investigators. Combined, these dedicated folks formed a compelling case that Earhart was able to transmit timed radio messages that coincided with low tide periods on Nikumaroro.

TIGHAR experts point out that Earhart’s Electra’s electrical generator was installed on the port or left engine. A working generator was vital to keeping the airplane’s battery charged so she could broadcast distress calls. To do that, Earhart would have to fire the generator engine periodically to charge her battery. That could only be done when the tide was low as there’s no safe way to run the engine while the propeller was buried in water.

TIGHAR experts point out that Earhart’s Electra’s electrical generator was installed on the port or left engine. A working generator was vital to keeping the airplane’s battery charged so she could broadcast distress calls. To do that, Earhart would have to fire the generator engine periodically to charge her battery. That could only be done when the tide was low as there’s no safe way to run the engine while the propeller was buried in water.

The TIGHAR team meticulously researched high and low tide times on Nikumaroro from July 2 to July 7, 1937. These were the dates that stations recorded radio calls on the 3105 and 6210 frequencies and triangulated them to Nikumaroro. Given that there are two high and two low daily periods to the world’s tide systems, the times and heights of Nikumaroro were known. The team then extrapolated radio transmission times and found they perfectly fit with low tide times on Nikumaroro.

Tide height and times predictably vary with monthly cycles. Certain times of the month have small tides which progressively increase to cyclical big tides. Graphs indicate that the low tide cycle period on Nikumaroro occurred at the beginning of July, 1937. By the second week of July, the mean high tide level increased by 1.4 meters or 4 ½ feet. Then, daily tides wouldn’t drop enough to let the Electra’s engine run.

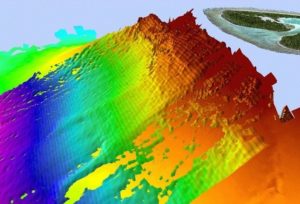

Gillespie and the TIGHAR investigators surmise that by July 7, rising tides and surf washed the Electra free from the reef where it slid down a steep underwater slope extending over 1,000 feet below the surface. While the main part of the plane was gone, it’s entirely likely that the severed landing gear remained trapped in a reef crevice for a number of years. Finally, wave, wind and water forces took the remaining wreckage to the depths.

Underwater Searches for Earhart’s Electra

TIGHAR volunteers have organized four different underwater search expeditions in attempts to locate Amelia Earhart’s Electra wreckage. Based on a high degree of probabilities and the preponderance of information/evidence, they conclude that Earhart’s Electra was washed off the reef and came to rest somewhere along an underwater slope. That could be anywhere from a few hundred to a few thousand feet deep.

These high-technology ventures aren’t cheap. TIGHAR raised several million dollars in donations and employed top scientists equipped with state-of-the-art underwater search vehicles. These remotely operated machines produced interesting results. However, definitive proof remains elusive despite the 2017 expedition identifying 41 potential targets with 25 of these being high-interest.

These high-technology ventures aren’t cheap. TIGHAR raised several million dollars in donations and employed top scientists equipped with state-of-the-art underwater search vehicles. These remotely operated machines produced interesting results. However, definitive proof remains elusive despite the 2017 expedition identifying 41 potential targets with 25 of these being high-interest.

TIGHAR’s first underwater venture involved SCUBA divers examining the reef’s fringes for trace evidence like landing gear pieces or shredded metal. Nothing showed up at shallow depths, which is not surprising given time’s passage. Next, an older submersible patrolled deeper regions but lost control due to rough surface weather. The latest underwater inspections involved ocean research equipment from the University of Hawaii.

2015 and 2017 expeditions used both the proven side-scanning sonar search and an open remote operating vehicle (ROV) which is an underwater drone with advanced optic cameras. These grid-patterns covered a 1.2 square mile patch off the northwest tip of Nikumaroro, down to 2,000 feet along a 60-70 degree slope. This tough terrain hosts vertical cliffs with many ragged shelves and crevices where plane wreckage could have hung up.

2015 and 2017 expeditions used both the proven side-scanning sonar search and an open remote operating vehicle (ROV) which is an underwater drone with advanced optic cameras. These grid-patterns covered a 1.2 square mile patch off the northwest tip of Nikumaroro, down to 2,000 feet along a 60-70 degree slope. This tough terrain hosts vertical cliffs with many ragged shelves and crevices where plane wreckage could have hung up.

Currently, the TIGHAR team has a particular image in mind that they refer to as an “anomaly” and a “high-interest target”. Its size and shape are consistent with an aircraft of the Electra’s design and sits at the 600-foot depth, right in the downward path from the suspected debris in the Bevington photograph. Future underwater searches with more advanced equipment are planned and funding is being raised.

2018 Analysis of the 1940 Nikumaroro Bones

While the combined information of radio calls, matching artifacts and suspected wreckage debris are fascinating, they’re still only circumstantial. That’s barely the case anymore with human bones found on Nikumaroro Island by a British work party in 1940. Now, a world-respected forensic anthropologist and osteologist recently stuck out his neck—and his reputation—by reexamining the original bone descriptions and recorded measurements

Dr. Richard Jantz, Professor of Osteology and Anthropology at the University of Tennessee, evaluated 1941 information about the Nikumaroro bones using his extensive experience and modern computerized Fordisc technology. Jantz concludes with over 99 percent probability that the Nikumaroro bones fit Amelia Earhart’s profile. In absence of evidence to the contrary, Jantz stands firm that a convincing argument proves those now lost bones belonged to Earhart.

Dr. Richard Jantz, Professor of Osteology and Anthropology at the University of Tennessee, evaluated 1941 information about the Nikumaroro bones using his extensive experience and modern computerized Fordisc technology. Jantz concludes with over 99 percent probability that the Nikumaroro bones fit Amelia Earhart’s profile. In absence of evidence to the contrary, Jantz stands firm that a convincing argument proves those now lost bones belonged to Earhart.

In 1940, the British constructed a small post on Nikumaroro Island as part of the Phoenix Islands settlement program. It was partly to establish pre-World War II sovereignty and partly to build the new LORAN navigation system. Workers first located a human skull in the summer and buried it. In the fall, more bones showed up at the Seven Site area and speculation started they may be those of lost pilot, Amelia Earhart.

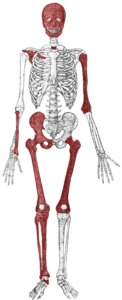

British authorities made a cursory search and found 13 human bones in total. These were silently shipped to the Medical Science Center in Suva, Fiji where Dr. D.W. Hoodless examined the major bones, recording measurements typical for anatomical practices of the day. Recovered bones included:

- Skull

- Lower mandible or jaw

- Scapula or shoulder blade

- Two upper region vertebrae

- Upper rib fragment

- Humorous or upper arm

- Radius or lower arm

- Innominate or hip

- Two femurs or thighs

- Tibia or shin

- Fibula or shaft

- Navicular or ankle

Dr. Hoodless recorded four skull measurements and three long bone measurements. He wrote these on a neat and legible foolscap paper, but there are no photo records or any information about bone disposal. There is also no mention of dental details that have been used for skeletal identification for decades. Hoodless gave his opinion that the Nikumaroro bones belonged to a middle-aged European male of stocky build.

Dr. Jantz is professionally respectful of Dr. Hoodless’s observations and recordings. He points out that Hoodless was a medical teacher at the Fiji school and had a basic anatomic understanding. However, Hoodless wasn’t trained in anthropology, and forensic osteology was an undeveloped discipline in that era.

Dr. Hoodless relied on a 19th-century skeletal rating system called Pearson’s Formula. It depended on a human bone measurement table developed when statures were smaller due to lesser nutrition and poor development conditions compared to 20th-century human evolution. Hoodless deducted that since the Nikumaroro skeleton suggested a tall and strong individual, it was likely a bigger and mid-aged male. Skull descriptions were consistent with known European racial features.

Dr. Hoodless relied on a 19th-century skeletal rating system called Pearson’s Formula. It depended on a human bone measurement table developed when statures were smaller due to lesser nutrition and poor development conditions compared to 20th-century human evolution. Hoodless deducted that since the Nikumaroro skeleton suggested a tall and strong individual, it was likely a bigger and mid-aged male. Skull descriptions were consistent with known European racial features.

Varying opinions surfaced about the accuracy of the Nikumaroro skeleton’s identification. A 1998 study of Hoodless’s measurements by two experienced anthropologists questioned the stocky male conclusion. They suggested the bones belonged to a tall European woman. In 2015, two different anthropologists defended Hoodless’s original findings.

This debate caught eminent forensic anthropologist/osteologist Richard Jantz’s interest. He decided to objectively look at Hoodless’s measurements and apply the 21st-century Fordisc measurement database to 20th-century information. To do that, Jantz worked with the same forensic photography team that analyzed the Bevington photograph.

Jantz and his associates realized they needed accurate estimates of Amelia Earhart’s body measurements. They worked with historic photos where they identified Earhart’s humorous, radius and tibia bone lengths. They estimated Earhart’s bone circumferences and joint structures. The team also measured Earhart’s known clothing kept at the Purdue University museum.

In conclusion, Jantz and associates established Amelia Earhart was 5’7”-5’8” tall, weighed approximately 130 lbs., had narrow, man-like hips and showed sturdy ankles. Her calculated bone measurements, based on the Fordisc database and the modern Mahalanobis distance scale that replaces the old Pearson’s Formula, perfectly fit with Hoodless’s figures. Jantz also took original skull measurements into account, concluding they were most probably female and definitely of the European race.

In conclusion, Jantz and associates established Amelia Earhart was 5’7”-5’8” tall, weighed approximately 130 lbs., had narrow, man-like hips and showed sturdy ankles. Her calculated bone measurements, based on the Fordisc database and the modern Mahalanobis distance scale that replaces the old Pearson’s Formula, perfectly fit with Hoodless’s figures. Jantz also took original skull measurements into account, concluding they were most probably female and definitely of the European race.

Richard Jantz deferred to a balance of probabilities based on the preponderance of information when he concluded the Nikumaroro bones were Amelia Earhart’s. He states that every detail of Hoodless’s measurements supports an Earhart finding and nothing excludes it. Hoodless notes, and Jantz confirms, the bones showed evidence that taphonomic processes modified the bones’ morphology—meaning they’d been picked over by crabs. Jantz points out that Earhart was known to be in the Nikumaroro area at the time the bones date to, she was never otherwise found and that all types of artifacts, photographs, archival and analytical information corroborate his conclusion.

To quote Richard Jantz, “Until definitive evidence is presented that the remains are not those of Amelia Earhart, the most convincing argument is that they are hers.”

What Really Happened to Emilia Earhart?

Based on the preponderance of information—call it evidence—a convincing picture emerges of what really happened to Amelia Earhart. She was an accident waiting to happen and her adventuresome, pushing-the-limit style caught up with her. Likely, she perished an agonizing death straight out of a horror movie.

Earhart and navigator Fred Noonan probably got unknowingly pushed off-course by northwest winds as they crossed the equator. They had a cloudy night that prevented Noonan from taking a celestial or star fix. Magnetic compass readings are notoriously unreliable at the equator just as they are at the poles. Waiting for sunrise and getting a 157/337 bearing line was their insurance policy.

By sunrise, when they established their baseline, they were already well south of Howland Island. They also had cloud-spotted daylight conditions when reflections from clouds looked exactly like small island landmasses. Even if they were in the range of Howland, it would have been nearly invisible regardless if flying low at 1,000 feet.

Earhart probably had a small fuel reserve as she flew back and forth along the compass line. She would have watched this like a hawk as the last thing any aviator wants is to ditch at sea. That’s a gamble with little win chance. Instead, Earhart would have taken advantage of any land base which turned out to be Nikumaroro Island.

Historical tidal records show that Nikumaroro had an extremely low tide on the morning of July 2, 1937. Earhart would have picked a long, flat beach option like the northwest coral shoal. From the air, it’d look smooth. But on the surface, it was a treacherous trick of rocky fissures and tire-cutting spears.

Probably, Earhart’s Electra set down on the shoal and experienced the same landing gear collapse this plane was famous for. They might have suffered personal injuries—particularly Fred Noonan—which Betty Klenck’s notebook indicates a male was badly hurt. The first thing a stranded aircrew would do is attempt radio communication. They’d do that as often as circumstances allowed.

Probably, Earhart’s Electra set down on the shoal and experienced the same landing gear collapse this plane was famous for. They might have suffered personal injuries—particularly Fred Noonan—which Betty Klenck’s notebook indicates a male was badly hurt. The first thing a stranded aircrew would do is attempt radio communication. They’d do that as often as circumstances allowed.

Within a few hours—as midday approached—the crash survivor(s) would have to move off the exposed beach and seek shade. They’d also need water. Nikumaroro had no natural freshwater supply which is why it was uninhabited. July is the dry season for Nikumaroro and finding potable water would be a serious and immediate challenge.

No one has a reliable theory of what happened to Fred Noonan. Nothing other than the sextant box turned up from Noonan, unlike evidence of Amelia Earhart. Possibly, Noonan remained with the wreckage and was washed over the reef. However, significant evidence exists that Amelia Earhart survived for some time.

Humans can live a long while without food. Not so without water—especially at the equator in full sun and 100+ degree heat. Amelia Earhart would have sweated 1liter/2pints of water per hour. Without replenishment, she’d soon suffered dehydration and gone into medical distress starting with cognitive confusion followed by neural-muscular impairment and multiple organ failures.

Humans can live a long while without food. Not so without water—especially at the equator in full sun and 100+ degree heat. Amelia Earhart would have sweated 1liter/2pints of water per hour. Without replenishment, she’d soon suffered dehydration and gone into medical distress starting with cognitive confusion followed by neural-muscular impairment and multiple organ failures.

Within a week with low water—ten days at the most—Amelia Earhart would have been an incapacitated castaway. She’d lapse in and out of consciousness and lay there defenseless. There was no escaping her final fate.

Nikumaroro Island is no exotic South-Seas getaway. It’s a hostile environment ruled by survival of the fittest. At the apex of Nikumaroro land predators are giant coconut crabs. These behemoths measure 3-feet across and weigh 10 lbs. They hunt in hordes using enhanced olfactory senses.

Earhart probably perished as she lay exhausted and dehydrated in the Nikumaroro Island sand. Slowly… one… then another… then many crustaceans feasted on Amelia Earhart—disarticulating and spreading her bones about Seven Site.

POST PUBLICATION NOTE: 27 July 2019

There might be a breakthrough in solving Amelia Earhart’s disappearance. This August, Dr. Robert Ballard will lead an underwater expedition sponsored by the National Geographic Society, the Ocean Exploration Trust and The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR). Ballard’s vessel, the E/V Nautilus, is a brand new, state-of-the-art research ship equipped with the most advanced subsurface equipment in the world. If anyone and any equipment is capable of finding Earhart’s wrecked plane, it’s this crew.

Dr. Ballard comes with experience in underwater exploration and a proven track record. Ballard is best known for finding the Titanic, the German battleship Bismark, and John F, Kennedy’s patrol boat, the PT109. In hundreds of ventures, Ballard has located many ancient ships as well as discovering the life-producing hydrothermal vents near the Galapagos Islands.

Hopefully, Dr. Robert Ballard and his team can close the book on what really happened to Amelia Earhart. The National Geographic show airs in October 2019. In the meantime, you might want to read, reread, or bookmark this blog post. Here’s the link to the National Geographic news release:

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/2019/07/bob-ballard-found-titanic-can-find-amelia-earhart-airplane/