This post is part of a new delivery for Dyingwords.net. It’s not sent out in my bi-weekly email, rather it’s a post about life and relationships that followers can discover on their own. From the start of Dyingwords.net, thirteen years ago and over 400 articles, the tagline has been “Provoking Thoughts on Life, Death, and Writing”. That hasn’t changed. However, most of my posts are/were on the death side of things when, at this stage, I’m thinking more about the life side of things.

This post is part of a new delivery for Dyingwords.net. It’s not sent out in my bi-weekly email, rather it’s a post about life and relationships that followers can discover on their own. From the start of Dyingwords.net, thirteen years ago and over 400 articles, the tagline has been “Provoking Thoughts on Life, Death, and Writing”. That hasn’t changed. However, most of my posts are/were on the death side of things when, at this stage, I’m thinking more about the life side of things.

Two things brought about this post. One is a thought leader named Sahil Bloom who linked the content of this article originally written by Kurt Armstrong and published it on his website. I give full attribution to Mr. Armstrong. The other is a difficult period a dear friend is going through in their long time relationship.

I’ve never had anything like a real career, only a long and varied string of jobs. I grew up working on the family farm, and then had jobs as a roofer, a groundskeeper at a rural hospital, and a mineral-bagging-machine operator in an unheated feed mill one frigid Manitoba winter. I spent a year as a photographer and store manager in a tiny portrait studio just as digital cameras were beginning to consign film cameras to obsolescence.

I worked for three years as a barista at one of Vancouver’s top-rated independent coffee shops. I’ve been a magazine editor, a sessional lecturer in a couple of liberal arts schools, a glazier’s assistant, a mason tender, a plumber’s labourer, and a daycare worker. One winter I lived in a simple little cabin—no plumbing, no electricity—and I made homemade soap over a wood stove and sold it at craft sales. In my twenties and thirties, I spent many of my summers planting close to half a million trees on countless logging clear-cuts between Hyder, Alaska, and Dryden, Ontario.

And for twelve years now I’ve had a hybrid operation, juggling a one-man autodidact home-repair business and part-time lay ministry at a little Anglican church in Winnipeg. My basic MO in both roles is simple: repair and remain.

I don’t have the know-how to build you a brand-new house, but I can help fix pretty much anything in your old one. If you do, in fact, need a new house, I’ll send you to Francesco or Myron, or James and Fiona, all of them trustworthy builders and fine people. Odds are the house you’re in right now needs a few updates and minor upgrades, and I’d be happy to help with whatever you need done: add some new windows, open up some walls, replace the old basement stairs, tile the backsplash. Repair and remain.

Same with pastoring: no point thinking you need a brand-new life, but, well, let’s not kid around—you could use some serious updates and upgrades yourself.

Let’s say time comes to gut and renovate your bathroom: I can help you with that—demolition, framing, reworking the plumbing, moving some electrical, installing some mould-resistant drywall, maybe some nice tile for the floor and some classic glazed ceramic three-by-six subway tile for the tub surround. Should take a month or two, depending on what all’s involved.

And as for you, hey, for the sake of your wife and kids, I think you better quit the flurry of furtive late-night texts to the sexy young co-worker and cut back a bit on your recreational drinking because wine is a mocker, so goes the proverb, as if those Facebook posts of you at the bar last week weren’t proof enough.

Repair and remain. Work with what you’ve got. Sit still for a moment, take stock, make some changes. Big changes, if necessary.

David and Ruth called me once to unclog their bathroom sink. Someone had dropped a nail clipper into it a decade ago, but now the drain was rusted and when I went to loosen the nut, the steel sink cracked and split, but it was an old sink so I couldn’t find a matching one to replace it with, so that meant the old vanity had to go too, but that left an odd footprint on the curled, old linoleum, so then the flooring had to go too, and, well, if you’re going that far, you might as well put in a new tub. And so on.

You get the picture. Renominoes. In the end, a house call to help deal with a bathroom sink with a nail clipper jammed in it led to six weeks’ work and a bill in the teens with three zeros.

Last year, in the middle of the pandemic, a man I haven’t seen in more than fifteen years called me up to weep on the phone because he was having a difficult time loving his kids. He had started to feel resentment toward them because, he said, the kids had taken so much away from him he barely knew who he was anymore. “I called you because I knew you’d be gentle with me,” he said. That I can do.

Six years ago, a guy I barely knew cornered me after church and asked if I could meet him for breakfast, and when we met, he told me he was this close to walking out on his wife and kids. Since then, he and I have been meeting up every couple of months or so. Last year he told me he wouldn’t still be married if it weren’t for all those conversations over greasy bacon and eggs over easy. Well and good, I say, but the truth is he’s the one doing the hard work. He’s the one who’s got to live his life. All I have to do is buy breakfast, and sit, and listen.

Repair and remain.

That’s how I work, and it’s what I advise. I don’t know how things are going to turn out in your life or in your marriage or with your kids. Nobody does. Maybe it will all get a whole lot worse, who’s to say. But a brand-new house won’t fix your troubles any more than a fresh start with a fascinating new somebody will. Don’t tell me; I already know it would be easier to just cut and run, because I know how hard it is to live with other people, four of whom are also stuck having to live with brooding, melancholy me. I have planted spruce saplings on the steep, thorny, overgrown slopes of the Rocky Mountains in snowstorms in June.

I once heaved a three-hundred-pound cast-iron tub up and out the second-story window of an old house. And when I worked for a bricklayer, he and I took down a concrete-and-rebar-reinforced cinderblock wall with sledgehammers. But this—doing my best to be a loving husband and father in the trauma and tedium of the day-to-day—is without question the hardest thing I’ve ever done.

Over the past dozen years I have had hundreds of pastoral conversations, mostly with young men, about the challenges of family life. They tell me it’s exhausting, that there’s no more free time, that they’re having a hard time setting aside their dreams and wishes, that kids can be unbearably frustrating. I get it. They tell me that the marriage isn’t what it used to be, that they don’t really have anything in common anymore, that the passion’s gone, that she isn’t who she used to be, that the sex isn’t what it used to be, that they’re tired of all of it.

I sip my coffee and nod in agreement with every word. I understand. I feel it too. It’s the same at my house. Marriage is hard.

But when they say, “I’m thinking of leaving,” I think, Now hang on a sec. You had me right up to that last bit. Fine: you’ve changed; she’s changed; life has changed. And the kids—well, they’ve disrupted, interrupted, confronted, confounded, and otherwise fundamentally altered everything. All very, very hard. And yes, sometimes it feels impossible. I know what it’s like to feel trapped, and my wife undoubtedly knows what it’s like to feel trapped, because she’s stuck with me, the more irritable and moody ingredient in our marriage. But you’re thinking of leaving? What is that going to fix?

We have, all of us and to varying degrees, been duped by the sales pitches, the flashing cascade of advertisements traipsing through the sidebar. That jam-packed flow of ads is full of shiny new things, new techniques, new experiences that promise to finally alleviate the so-far insatiable, burning, lonely, primordial ache. Bono laments, “I still haven’t found what I’m looking for.” Springsteen cries out, “Everybody’s got a hungry heart.” k.d. lang bemoans the “constant craving.” Augustine says, “Our hearts are restless.”

I used to blame advertisers for that restlessness and dissatisfaction, but I don’t think that’s right. We were already restless; we always have been. The advertisers just figured out how to nurture, tend, exacerbate, and capitalize on the pre-existing condition, that innate restlessness, promising that something new is going to set all to rights. When the flashing sidebar connects that hand lotion, those hiking boots, a beach vacation, or some rugged SUV with satisfaction, joy, and inner peace, it sure feels like we’d be suckers not to buy it. And when that thing inevitably disappoints, we hardly even notice. There’s always something new to buy.

That narrative of elusive satisfaction isn’t just something we’re repeatedly being told; it is a story we’re literally buying into all the time. No surprise, then, that when our beloved to whom we once upon a time “pledged our troth” inevitably disappoints, we start thinking it might be time to get a new beloved.

That narrative of elusive satisfaction isn’t just something we’re repeatedly being told; it is a story we’re literally buying into all the time.

I have come to think that renovation work is not inherently a sign of fashion-driven, bourgeois, consumerist excess; that beauty is not superfluous; and that a good renovation is a good investment. Taking care of your house is a wise and pragmatic thing to do. The integrity of a house means that all the parts and systems work as a whole, from ridge cap to footing and everything in between. Roof trusses, studs, joists, shiplap, plumbing supply and waste, eaves, windows, flooring, faucets, switches: your house will function as a house when it is well built and well maintained. Integrity of form, function, usability, and beauty. If it’s poorly made, or when it starts to fall apart, the integrity of the whole thing suffers. Give it enough time and a leak in the roof or a leak from a drain will ruin the whole thing.

If you ignore the little things long enough, something as small as a nail clipper can make for two days of demolition and a trailer filled with an old sink, outdated vanity, faded linoleum, some lath and plaster, old plumbing, a thirsty old toilet, and so on. I can haul those few thousand pounds of junk to the landfill and rebuild your bathroom. But in the end, when it’s all put back together again, what you have will still be the spot to do the same basic grooming and human-waste disposal.

Pay attention and mind the details and you save yourself a lot of hassle and money. That slow corrosion that comes if you ignore the small, nagging troubles of your life has the potential to wreck a family the way a nail clipper can wreck a bathroom. And somebody’s going to pay for it, even if it isn’t you. Mostly it will be the kids, plus the ongoing emotional and spiritual costs divvied up among the friends, family, and community who witnessed your vows, who backed you as you struggled along, who loved you then and still love you now.

Because however it may sometimes seem that circumstance, fortune, and your exasperating spouse are conspiring to sabotage your happiness and peace of mind, the one certain, irrefutable common factor in all your circumstances is you. You are the bearer and carrier of grief, disappointment, frustration, and heartache, just as you are also the source of much of the same. So it goes.

I’ve said it more than once to some guy across the table who tells me he’s planning to leave his marriage: You should stay. Sit in the awful, agonizing sorrow of it all, and figure some things out. Your life is very hard. I know you’ve thought it through more than I can imagine; I know you’ve calculated the cost-benefit, weighed your options; and all that is fine and good. There is no way of knowing how this will play out in your very real life. Nobody can predict the future. Something has to give, yes. But it doesn’t need to be this. I think you should stay.

It’s a tough sell. I understand, because my undisciplined imagination, formed like everyone else’s by countless half-minute ads and building-sized billboards, frolics among fantastic, glamorous possibilities of something other than what I’ve already got. It’s a cornucopia of options, with countless cathedrals and priests promising salvation at the marketplace, be it a new app, new phone, new car, new house, new job, new city, or new spouse. The promise is always the same: this thing will make you happy. Never mind trying to fix what you’ve got. Just get a new one and start over.

Repair and remain sounds simple because it is. But simple is not the same as easy. “For better, for worse,” we say, and everyone likes to stay when it’s the better. But staying through the worse—that’s the whole point of the vow, for Christ’s sake.

Repair and remain sounds simple because it is. But simple is not the same as easy.

Mostly they do what they’ve already decided to do, and they leave. My track record for counselling couples to stick it out is pretty poor. I still think the better part of wisdom says stay. Endure. Wrestle. Suffer. Struggle. Keep working. Your heart is restless, my heart is restless, all our hearts are restless, “until they find their rest in Thee”—a rest that may well be found in full only after our death. So be it. Until then: stay.

Repair and remain.

Repair and remain.

Repair and remain.

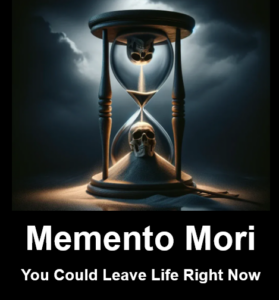

Memento Mori, translated from Latin, means “Remember, you must die”. It’s a wake-up that your life course could be radically altered and end at any moment. Our lives are impermanent, in constant flux and change, flowing through time towards entropy and inevitable death that might happen without warning. Memento Mori — You could leave life right now.

Memento Mori, translated from Latin, means “Remember, you must die”. It’s a wake-up that your life course could be radically altered and end at any moment. Our lives are impermanent, in constant flux and change, flowing through time towards entropy and inevitable death that might happen without warning. Memento Mori — You could leave life right now.