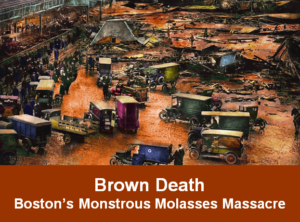

A massive molasses storage tank ruptured in downtown Boston, Massachusetts at 12:40 pm on Wednesday, January 15, 1919. 2.3 million gallons of liquid sludge, weighing over 12,000 tons, burst from the receptacle and sent a surge of brown death onto Boston’s streets. The sickly sweet wave was 40 feet high and moved at 35 miles per hour. When the sugary flood stopped, 21 people were dead and over 150 suffered injuries. Property damage was in the millions, and the legal outcome changed business practices across America. Sadly, the Boston Molasses Disaster, or Boston Molasses Flood, was perfectly preventable.

A massive molasses storage tank ruptured in downtown Boston, Massachusetts at 12:40 pm on Wednesday, January 15, 1919. 2.3 million gallons of liquid sludge, weighing over 12,000 tons, burst from the receptacle and sent a surge of brown death onto Boston’s streets. The sickly sweet wave was 40 feet high and moved at 35 miles per hour. When the sugary flood stopped, 21 people were dead and over 150 suffered injuries. Property damage was in the millions, and the legal outcome changed business practices across America. Sadly, the Boston Molasses Disaster, or Boston Molasses Flood, was perfectly preventable.

The molasses tank (reservoir or container, if you will) belonged to the Purity Distillery Company owned by United States Industrial Alcohol (USIA). It was 50 feet tall (five stories), 90 feet in diameter, and had a circumference of 283 feet. At the time, the Boston molasses tank was the city’s largest liquid storage facility. It was also the deadliest.

In January 1919, Boston was a happening place. The U.S. concluded World War I efforts two months earlier and was on the verge of Prohibition being enacted. Alcohol was in huge demand, both recreational for making spirits and industrial for manufacturing explosives. Molasses was a staple source for both, and Boston was an ideal spot for storing molasses.

Through Purity Distilling, USIA owned a strategic location on Commercial Street at Boston’s north end waterfront. It’s now a public place called Langone Park. The tank site was adjacent to a wharf where longshoremen could unload molasses tankers arriving from sugar cane plantations in the West Indies, pump the slurry mix to the receptacle, and then load it into rail cars when needed by USIA’s Purity distillery in Cambridge, west of downtown Boston.

The tank’s construction began in 1915, but it suffered delays. Completion occurred in 1917 and it went into operational use with little testing applied. Immediately, molasses leaks appeared at riveted seams where the metal panels overlapped. Many nearby residents, mostly Italian immigrants, complained of the unsightly mess and unfavorable smell. USIA’s response was not to fix the leaks but paint the tank brown to mask the molasses stains.

People complained about more than the appearance and the odor. Employees who worked around the tank heard creaks and groans coming from within the molasses storage unit. They felt shudders and shakes when the tank was loaded and unloaded, and they sounded their concerns about the structural integrity of the hastily-built monstrosity. Their voices fell on deaf management ears.

On January 12, 1919, the shaky tank took on a 1.3 million gallon load of Cuban molasses. The tank was at its highest-ever capacity with an overall weight of 26 million pounds. The molasses sat until the Wednesday morning when the sun came up and began an unusual temperature gain for that time of year.

Without warning, at 40 minutes past noon, the molasses tank ruptured at its bottom seams. A massive force sent metal debris flying as heavy-weight shrapnel with the gooey molasses mess radiating in a four-story-high wave knocking buildings off their foundations, smashing their wood frames to smithereens, toppling freight cars, and killing these innocent people:

Patrick Breen, age 44

William Brogan, age 61

Bridget Clougherty, age 65

Stephen Clougherty, age 34

John Callahan, age 43

Maria Di Stasio, age 10

William Duffy, age 58

Peter Francis, age 64

Flaminio Gallerani, age 37

Pasquale Iantosca, age 10

James Kenneally, age 48

Eric Laird, age 17

George Lehaye, age 38

James Lennon, age 64

Ralph Martin, age 21

James McMullen, age 46

Cesar Nicolo, age 32

Thomas Noonan, age 43

Peter Shaughnessy, age 18

John Seiberlich, age 69

Michael Sinnott, age 78

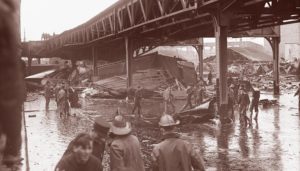

First responders were overcome with one main obstacle. That was trying to move in the 2 to 3-foot deep pool of semi-liquid molasses that thickened as the day cooled and the goo dropped to the ambient temperature of Boston’s wintertime. It took 4 days to recover nearly-unrecognizable bodies and decontaminate them so identification could be made.

Medical workers established a field hospital to treat assorted injuries like broken bones, crushed organs, and obstructed airways. Cleanup efforts took months. And the molasses smell remained ingrained in Boston’s air for years. Today, over 100 years later, local legend says you can still whiff molasses on hot summer nights.

The Investigation and Legalities Began

Someone had to be accountable for Boston’s monstrous molasses massacre. Those were the people managing USIA’s storage facility in North Boston, and the process would take six years. Eventually, no individual was prosecuted for a criminal act although the utter negligence displayed in (lack of) planning, overseeing, and commissioning the molasses tank’s construction was outrageous.

Two factors drove the need for such a large molasses container. First was the marketplace because, at the Roaring Twenties onset, there was a highly-profitable demand for recreational and industrial alcohol. The USIA executives wanted to capitalize on molasses-based alcohol products as quickly as possible. Strike while the iron’s hot, as they say.

Second was the onset of Prohibition. The Eighteenth Amendment was ratified the day after the Boston disaster, and to be in effect one year later. After that, the manufacture of recreational alcohol would be illegal and USIA wanted to stockpile as much as possible.

To corner the American molasses market, USIA needed bulk buying power and an economical supply chain including a convenient storage facility. They found it at Boston Harbor, and they relied on one man to oversee the construction project.

Arthur P. Jell was the USIA’s comptroller—their treasurer. Jell wasn’t an architect or an engineer. He had no basic building experience let alone constructing something as large and complex as a steel container capable of safely holding 12,000 tons, or 2.3 million gallons, of a substance weighing 1.4 times the mass of water.

Jell was an accountant. He was a bean counter and thought like one. Jell’s primary focus was on costs and speed. He was also on a shaky career footing.

Arthur Jell was under orders to get the tank built and get it built fast. The USIA bosses assigned Jell to lead the tank project in 1915 which was the early stages of WWI where steel supplies were running scarce through high wartime productions. By 1917, Jell only had the tank’s concrete foundation done. He was running late and under immense pressure to receive a pre-ordered and on-the-way Caribbean molasses shipment of 700,000 gallons.

If the tank wasn’t ready, the USIA executives would have to find another storage facility (of which there were none that size in America) or dump the molasses at sea. Either way was a major loss for USIA and for Arthur Jell himself.

If the tank wasn’t ready, the USIA executives would have to find another storage facility (of which there were none that size in America) or dump the molasses at sea. Either way was a major loss for USIA and for Arthur Jell himself.

Jell got the tank operational just in time to save the shipment. Through the low-bid contractor, Hammond Iron Works, the molasses receptacle was hammered together and filled without proper testing. And because the tank was a “receptacle” by definition—not a building or a bridge— the City of Boston did not require a permit for anything other than the foundation.

The tank’s structure had no approved plans, sealed drawings, listed specifications, professional oversight, or approved inspections and tight commissioning procedures. The project depended on a tight-fisted, building-ignorant manager and a corner-cutting construction company operating on a profit-first agenda.

Hindsight is usually 20/20. Stephen Puleo does hindsight carefully in his scholarly 2003 book on the Great Boston Molasses Flood titled Dark Tide. Here’s a quote from the book’s description:

For the first time, the story of the flood is told here in its full historical context, from the tank’s construction in 1915 through the multiyear lawsuit that followed the disaster. Dark Tide uses the gripping drama of the flood to examine the sweeping changes brought about by World War I, Prohibition, the anarchist movement, immigration, and the expanding role of big business in society. To understand the flood is to understand America of the early twentieth century – the flood was a microcosm of America, a dramatic event that encapsulated something much bigger, a lens through which to view the major events that shaped a nation. It’s also a chronicle of the courage of ordinary people, from the firemen caught in an unimaginable catastrophe to the soldier-lawyer who presided over the lawsuit with heroic impartiality.

For the first time, the story of the flood is told here in its full historical context, from the tank’s construction in 1915 through the multiyear lawsuit that followed the disaster. Dark Tide uses the gripping drama of the flood to examine the sweeping changes brought about by World War I, Prohibition, the anarchist movement, immigration, and the expanding role of big business in society. To understand the flood is to understand America of the early twentieth century – the flood was a microcosm of America, a dramatic event that encapsulated something much bigger, a lens through which to view the major events that shaped a nation. It’s also a chronicle of the courage of ordinary people, from the firemen caught in an unimaginable catastrophe to the soldier-lawyer who presided over the lawsuit with heroic impartiality.

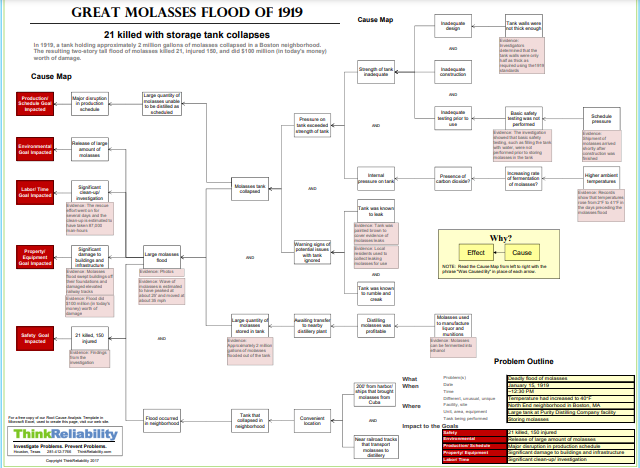

Stephen Puleo’s Dark Tide does a deep dive into the structural failures and cause-effect details for why the molasses tank ruptured. So does a highly-respected company called Think Reliability that does cause-mapping, or root-cause analysis, of significant events. Here are the main points of what occurred to cause the failure of USIA’s giant molasses tank in downtown Boston:

Inadequate Design — The tank’s steel walls were half as thick as best engineering practices should have designed them. This was to save cost. The rivets were inferior, too small, and improperly installed. Again, to save cost as well as speed the timeline. The steel panels had low manganese levels which made the tank brittle at low temperatures. Once again, cost saving.

Inadequate Supervision — Arthur Jell did not understand construction methods and engineering standards. He focused on cost and speed instead of reliability and safety. Hammond Iron Works focused on profit and were not supervised or overseen by proper drawings and specifications as well as competent inspectors. Once more, speed and cost drove the bus with no regard for end-use safety.

Environmental Influence — Setting aside the bad design and lack of oversight, Boston’s environment was a wild card. On January 12, when the tank took the 1.3 million gallon Cuban load, there was a smaller amount of cold molasses sitting at the tank’s base. The Cuban molasses was heated on the tanker so it could be pumped to the storage receptacle. The thermal inequality of hot molasses sitting on cold molasses started a fermentation reaction that off-gassed carbon dioxide and raised the tank’s internal pressure. When the morning temperature unusually rose on January 15 (from overnight of +2F to 40F at noon) the pressure exceeded the steel strength.

Ignored Warning Signs — The creaks and groans and worker warnings went unheard or ignored by persons in USIA’s management. To “paint the tank brown” rather than fix the problem would amount to gross negligence in the current industrial safety world. The courts, today, would think along the same lines and it’s from the litigation following Boston’s monstrous molasses massacre that safety rules—specifically in the design, permitting, and inspection of building projects significantly changed. For the better.

Civil litigation began immediately following the Boston Molasses Disaster. An abundance of lawyers filed 117 separate lawsuits against United States Industrial Alcohol and its subsidiary Purity Distillery. The suits amalgamated into one class-act procedure which was the first time in American history that a class-action of this magnitude began. It set the stage for all other class-action or representative-action legal proceedings.

It took six years to wind through the courts. USIA used the defense that the tank had been an act of sabotage—domestic terrorism—committed by Italian anarchists. There was absolutely no proof of this, but the defense tactic took hold the day following the tank rupture. The Boston papers reported that the tank had “exploded” which indicated some sort of explosive device being set off rather than natural forces of pressure exceeding containment and carried out by gravity.

The presiding judge didn’t buy the explosion argument. In his judgment finding complete fault on behalf of Purity and USIA, the judge wrote, “The tank was wholly insufficient in point of structural strength, insufficient to meet either legal or engineering requirements. The scene was unparalleled in the severity of the damage inflicted to the person and property from the escape of liquid from any container in a great city.” In conclusion, the judge ordered USIA to pay the plaintiffs $628,000 which is approximately $10.12 million in today’s currency.

The presiding judge didn’t buy the explosion argument. In his judgment finding complete fault on behalf of Purity and USIA, the judge wrote, “The tank was wholly insufficient in point of structural strength, insufficient to meet either legal or engineering requirements. The scene was unparalleled in the severity of the damage inflicted to the person and property from the escape of liquid from any container in a great city.” In conclusion, the judge ordered USIA to pay the plaintiffs $628,000 which is approximately $10.12 million in today’s currency.

Aside from the legal impact, American building processes changed after the Boston Molasses Flood. Jurisdiction upon jurisdiction required building projects to be professionally designed, properly constructed, and strictly inspected by competent authorities. Today, all major works are intricately designed and approved with architect/engineering stamps and carried out by qualified workers under legal permits.

And today, the site of the brown death—Boston’s monstrous molasses massacre—is a pretty park containing a Little League baseball field, a playground, and bocce courts. There’s a small plaque paying tribute to its horrific past.