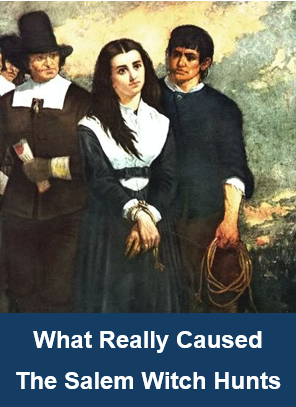

The Salem witch hunts and mass executions of innocent victims falsely accused of sorcery is an American historical black mark. Through June to October of 1692, Puritan authorities in Salem, Massachusetts hung nineteen citizens after trying and convicting them for witchcraft. They crushed another man to death with heavy stones and let five others perish—shackled in chains. Two imprisoned souls were mere children.

The Salem witch hunts and mass executions of innocent victims falsely accused of sorcery is an American historical black mark. Through June to October of 1692, Puritan authorities in Salem, Massachusetts hung nineteen citizens after trying and convicting them for witchcraft. They crushed another man to death with heavy stones and let five others perish—shackled in chains. Two imprisoned souls were mere children.

Today, all Salem witch hunt victims are officially exonerated. This terrible debacle became the poster case for trumped-up accusations and wrongful convictions. In fact, the term “witch hunt” is symbolic for going after those profiled for a vengeance need or paranoid forces “out to get someone”. Even a past United States president Twittered-on about witch hunts.

This horrific travesty of malicious injustice was an American turning point. Historians call the Salem witch trials the rock upon which theocracy shattered. They were the perfect storm of isolationism, religious extremism, fanaticism, and divided socio-economic structure. The witch trials were also unprecedented as bad jurisprudence and horrible miscarriages of justice.

Today, few educated or rational people believe in evil witchcraft or black magic. (Modern peaceful Wiccan practitioners are a different matter.) That old destructive medieval and ignorant mindset sieved from America after the Salem witch trials. But, for over three centuries, few people understood why the disaster happened. Various theories suggested Freudian mass-hysterics, a widespread fungus causing mind-altering behavior, and even meddling by alien forces aligned with the dark side.

Now the truth is out there. A meticulous, scientific study by two American academics published in the book Salem Possessed wraps up the witch hunt reason. It’s not some supernatural power or psychedelic drug. The answer lies in a complex mix of sociology, geography, demography, human psychology, genetics, pathology, and forensic science.

Something far more sinister than sorcery really caused the Salem witch hunts.

History of the Salem Witch Hunts

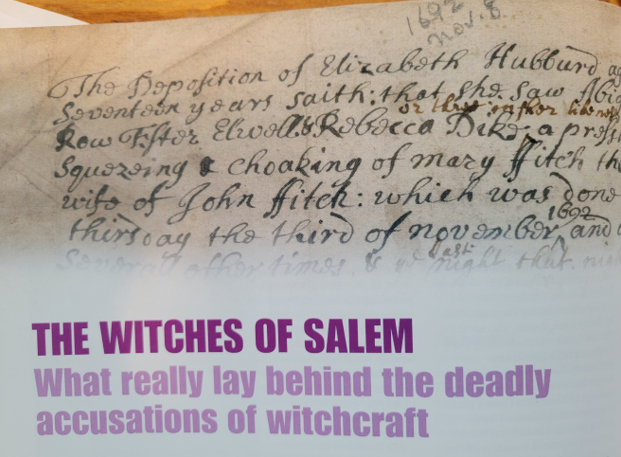

It trigged with teenagers. In January 1692, three bored girls played a game similar to today’s Ouija Board. They cracked eggs and separated the whites in a pan of cold water, then used imagination to decipher patterns divulging hidden secrets and foretelling future events. They got carried away. Soon they were writhing in fits and cramping into twisted contortions.

The girls were relatives of Salem Village vicar Samuel Parris, a Massachusetts Bay Puritan parishioner who referred the distorted girls to a local physician. The doctor found no medical cause for the girls’ discomfort. He suggested it was work of witchcraft and turned it back to the minister. The reverend sided with Satanic superstition and went about extracting accusations from the young girls.

They implicated three Salem women for bewitching and causing their erratic behavior—Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne, and Tituba. Good was known for tardy church attendance. Osborne was a loose-moraled beggar. And Tituba was a Carib slave house servant. The trio were hardly credible to Salem’s upper crust and certainly suitable scapegoats not equipped to defend themselves.

Good and Osborne fervently denied being witches. Despite intensive interrogation in magistrate’s court, they held to their denials. Tituba, on the other hand, confessed. She gave wild accounts of signing Satan’s book and offered crazy tales of human hogs, great black dogs, red cats, and yellow birds. Tituba also named of other Salem witches.

From there, everyone got carried away. Authorities rounded-up scores of witch suspects, hauling them before interrogatories. More people—women and men—confessed under duress and named more names. In a few months, nearly two hundred “witches” were accused, hunted down, and arrested in Salem and neighboring communities. Quickly, the arrests turned to trials and mass hangings began.

The 17th Century Salem Legal System

1692 was an important year in 17th Century Salem’s legal system. It coincided with a new charter for the Province of Massachusetts Bay following the 1680s King William War. The colonists were deeply divided in Salem and the surrounding area’s social structure. It was protective Puritism vs. progressive private enterprise. The King’s newly-appointed Governor, William Phip, arrived with the charter in January,1692—just as the witchcraft accusations arose.

The spiraling sequence of accusations, arrests and confession led to mass hysteria and a “thronged” legal system. To accommodate justice, Governor Phip convened a Special Court of Oyer (hearing) and Terminer (deciding). He appointed magistrates, judges and sheriffs based on local recommendations by powerful people in the religious sphere.

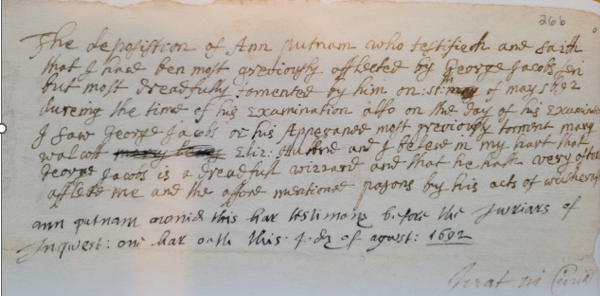

The Salem witch trials occurred long before the United States Constitution was a gleam in revolutionary eyes. Rules of evidence stemmed from English common law and principles based on religious doctrine. For witchcraft cases, evidence came from accusatory mouths of uneducated and manipulated common folk, not from corroborated independent and credible witnesses.

Once a citizen claimed their loss or discomfort was witchcraft caused, they laid a complaint against the accused before an appointed magistrate. If the complaint appeared credible by the magistrate’s standard, the accused was arrested and brought in for mandatory interrogation. This was well before the right to remain silent.

Interrogations were public events. Open questions by a panel and audience members given standing were standard procedure. Every effort pressed the accused to confess and reveal other witches. It was a Puritanical purging of Salem’s evils and a chance to rid society of undesirables. Once a grand jury heard interrogation evidence, they preferred an indictment and the ‘witch” was set on trial.

Witch trials depended on what’s called “spectral evidence”. This was testimony of the afflicted who claimed to see the apparition of the accused witch appear in a ghostly form while performing witchcraft upon them. Theologically, the court evidence relied on whether or not the accused gave the Devil permission to use their shape. The Salem witch courts contended the Devil could not perform evil acts using a person’s shape without that person’s expressed permission—therefore, if the afflicted complainant had seen the accused’s shape—it was in facto proof the accused was guilty of witchcraft and complicit with the Devil. According to Puritan law, the witch must die.

This convoluted logic resulted in immediate hangings and a compression death through layered stoning. It also caused deaths of those awaiting trial while shackled in dungeons. In three months, twenty-four innocent people were dead and many more awaited similar fates. That’s until someone accused Governor Phip’s wife of being a witch.

Suddenly, the executions stopped. Phip ordered an evidentiary review. It determined spectral evidence was inadmissible, noting it was not credible and highly prejudicial to the accused. Phip stayed the remaining execution warrants and commuted sentences, essentially freeing all those facing witchcraft allegations. Within three years, the Province of Massachusetts Bay officially exonerated all accused witches and ordered a consolidating day of fast and remembrance.

Cause of the Salem Witch Hunts

Many historians and writers pondered how normally rational people got so swept by the wind of witchcraft craze. Certainly, there was a mass psychological hysteria and paranoia. But the actual reason—the root cause—of why so many witch accusers and so many accused witches behaved so bizarrely was unknown. For years, suspected causes for bewitched symptoms like convulsing and hallucinating fell on the Claviceps purpurea fungus found in Puritan bread. It’s known for LSD-like side effects.

But a bread acid trip didn’t cut current standards, even though the mass hysteria was long explained by archaic superstitions of wanton witchcraft and the Devil’s demons. Everybody ate Puritan bread in Salem, and only a few presented weird symptoms. No, a rational look at the Salem witch hunts needed further investigation by reasonable and independent thinkers.

That rationality came from two Harvard-educated history professors at the University of Massachusetts who wrote the intriguing book Salem Possessed. Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum’s work took an in-depth look at the social, economic, and geographical factors affecting Salem’s citizens back when the witch hunts started. They also took a forensic approach to the psychological and pathological influences causing the complainant’s symptoms.

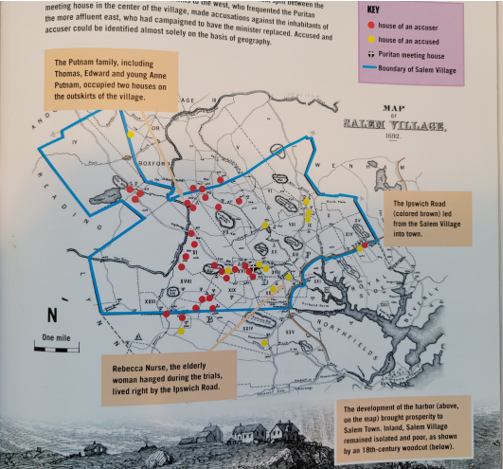

Boyer and Nissenbaum came to an astounding social conclusion. However, they weren’t the first to arrive there. In 1867, New England historian Charles W. Upham produced an accurate map of how Salem Village appeared in 1692. Then he plotted the houses where witch accusers and accused witches lived. Astonishingly, almost all accusers lived on the west side of Salem Village. The accused lived on the east side.

Salem Possessed’s authors concluded that if the Devil had come to Salem, he was being very choosy about which homes he visited. No, they concluded. The reason for the witch hunts had to lie in Salem’s history, and they were right.

Salem is one of the oldest European settlements in North America’s New England region. As the crow flies, it’s less than twenty miles northeast of downtown Boston. English immigrants of the Puritan faith first occupied Salem to establish a community based on their conservative views to protect old ways threatened by the age of Enlightenment and the then-liberal Anglican Church.

The Puritans were agricultural people. Naturally, they chose to settle in the best farmland which lay to the west of Massachusetts Bay. Over the course of eighty years—roughly four generations back then—the Puritans built a religious and agricultural society centered around what they called Salem Village. Today, the area is known as Danvers, Massachusetts which is a different jurisdiction from present-day Salem.

During the mid-1600s, a harbor community developed on Massachusetts Bay, east of the village. It became known as Salem Town. Commercially progressive settlers occupied Salem Town and focused on making money rather than praising the Lord and preserving old ways. As Salem Town grew, it pressed westward and crossed the border into the village. That didn’t sit well with the Puritan villagers.

Boyer and Nissenbaum uncovered a tangled history of feuds, jealousy, mistrust and hostility between the west Salem villagers and their eastern invaders. West Salem had two tightly knit prominent families who married within. The easterners were a mix of newcomers who married outside family lines. For some reason, everyone who displayed physical symptoms of being witch victims came from the two prominent Puritan families.

From a socio-economic and religious point, it’s clear the impact of commercial capitalism and the shifting role of the church left the backward Puritans threatened by their modern newcomers. It led to unbearable tensions which broke once the first bewitched symptoms showed in January of 1692. That opened a floodgate of superstitious opportunity to kill the eastern Salem villagers.

Salem Possessed makes a powerful argument that human personality partially caused the Salem witch hunts. If that be the Devil in humanity, then so be it. However, the Devil isn’t a good forensic reason for why the teen girls experienced peculiar symptoms like mood swings, cramps, and hysterical contortions. Something else was at work, and the pathology points at genetics.

Putting it bluntly, the Puritans were inbred. Their closed circle was more than religious and economic. They married within and secluded their gene pool. Huntington’s Chorea or Huntington’s Disease is common in people with dysfunctional genes. It’s a hereditary neurodegenerative illness with physical, cognitive, and emotional symptoms exactly like the west Salem village girls experienced. The gene mutation creates a protein that kills cells in the brain’s cerebral cortex.

Many adults in the Puritan community already had some stage of Huntington’s Disease. That impaired their thought processes as well as their offspring’s. Because of longevity in the Salem region and that power still clung to the Puritan Church in the late 1600s, Puritans made up the judicial force that persecuted the alleged witches. Their personality and pathology dysfunctions are what really caused the Salem witch hunts.

For three centuries, lore held that the witches of Salem were hung from scaffolding in the center of today’s Gallows Park. That’s not correct. Several years ago, the Gallows Project funded by the University of Massachusetts did a thorough research based on historical records and advanced forensic techniques like GPS analyzation and ground penetrating radar.

They conclusively identified the execution spot as a tree at Proctor’s Ledge. It’s right beside a Walgreens, and the community built a small memorial honoring the wrongfully accused witches of Salem.

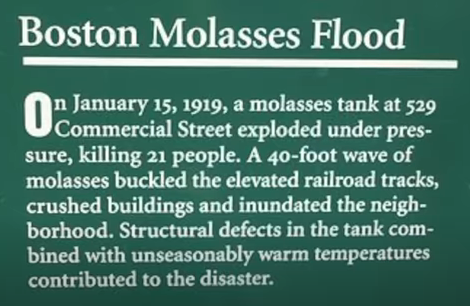

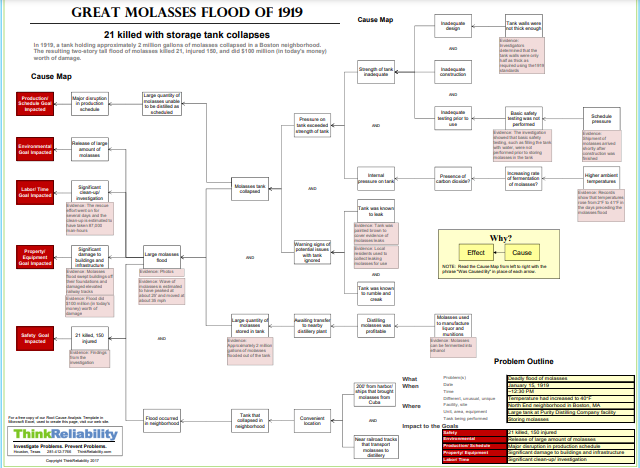

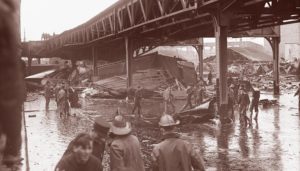

A massive molasses storage tank ruptured in downtown Boston, Massachusetts at 12:40 pm on Wednesday, January 15, 1919. 2.3 million gallons of liquid sludge, weighing over 12,000 tons, burst from the receptacle and sent a surge of brown death onto Boston’s streets. The sickly sweet wave was 40 feet high and moved at 35 miles per hour. When the sugary flood stopped, 21 people were dead and over 150 suffered injuries. Property damage was in the millions, and the legal outcome changed business practices across America. Sadly, the Boston Molasses Disaster, or Boston Molasses Flood, was perfectly preventable.

A massive molasses storage tank ruptured in downtown Boston, Massachusetts at 12:40 pm on Wednesday, January 15, 1919. 2.3 million gallons of liquid sludge, weighing over 12,000 tons, burst from the receptacle and sent a surge of brown death onto Boston’s streets. The sickly sweet wave was 40 feet high and moved at 35 miles per hour. When the sugary flood stopped, 21 people were dead and over 150 suffered injuries. Property damage was in the millions, and the legal outcome changed business practices across America. Sadly, the Boston Molasses Disaster, or Boston Molasses Flood, was perfectly preventable.

If the tank wasn’t ready, the USIA executives would have to find another storage facility (of which there were none that size in America) or dump the molasses at sea. Either way was a major loss for USIA and for Arthur Jell himself.

If the tank wasn’t ready, the USIA executives would have to find another storage facility (of which there were none that size in America) or dump the molasses at sea. Either way was a major loss for USIA and for Arthur Jell himself.

The presiding judge didn’t buy the explosion argument. In his judgment finding complete fault on behalf of Purity and USIA, the judge wrote, “The tank was wholly insufficient in point of structural strength, insufficient to meet either legal or engineering requirements. The scene was unparalleled in the severity of the damage inflicted to the person and property from the escape of liquid from any container in a great city.” In conclusion, the judge ordered USIA to pay the plaintiffs $628,000 which is approximately $10.12 million in today’s currency.

The presiding judge didn’t buy the explosion argument. In his judgment finding complete fault on behalf of Purity and USIA, the judge wrote, “The tank was wholly insufficient in point of structural strength, insufficient to meet either legal or engineering requirements. The scene was unparalleled in the severity of the damage inflicted to the person and property from the escape of liquid from any container in a great city.” In conclusion, the judge ordered USIA to pay the plaintiffs $628,000 which is approximately $10.12 million in today’s currency.