Everyone—you and me included—has heard their small inner voice speak. It might have been a muffled word of sage advice, a loud yell of urgent caution, or a simple suggestion towards the right move. Evolutionary, our subconscious source of wisdom has served us well—“Whoa! Don’t step outside the cave right now” to “Hey! This wheel and axle invention will be big.” But as real as intuition is, many people choose to ignore their instincts. How about you? Do you trust your gut feelings?

Everyone—you and me included—has heard their small inner voice speak. It might have been a muffled word of sage advice, a loud yell of urgent caution, or a simple suggestion towards the right move. Evolutionary, our subconscious source of wisdom has served us well—“Whoa! Don’t step outside the cave right now” to “Hey! This wheel and axle invention will be big.” But as real as intuition is, many people choose to ignore their instincts. How about you? Do you trust your gut feelings?

There are lots of terms for gut feelings. Intuition is the main one, but there’re differences of opinion as to what constitutes raw instinct, subtle intuition based on life experience, and plain old gut feelings—also known as the sixth sense, vibes, foresight, precognition, visceral nudges, being-in-the-world, hunches, and downright lucky guesses. These are socially-acceptable labels, not to be confused with pseudoscience stuff like tactic knowledge, remote viewing, morphic resonance, ESP, clairvoyance, and cryptesthesia. Then there’s a half-way, new-age idea called Grok. You might want to Google that.

What got me going on today’s post is a recent comment left on an old DyingWords thread where a fellow made a statement that relying on gut feelings amounted to as much as taking a ride on a Ouija board. “Hang on a moment,” I replied. “I have decades of investigation experience and, if there’s one thing I’ve learned, I’ve come to rely on my gut feelings—hunches, intuition, Grok, or whatever you wanna call them.”

Just a quick personal story before we move on to look at the philosophy, psychology, and physiology behind intuition as well as taking a test to see how much you trust your gut feelings. In 1985, I was part of a police Emergency Response Team (ERT or SWAT for Americans). We were sent to the frozen wilds of the Canadian north to arrest an armed and murderous madman. Michael Oros, the bad guy, got the drop on my partner and me just as I had this incredible gut feeling that he’d silently crept up behind us. I spun around right as the fire-fight started. Because of this intuitive gut feeling—this overpowering presence of imminent danger—I was able to react to save my life and probably the lives of other teammates.

Just a quick personal story before we move on to look at the philosophy, psychology, and physiology behind intuition as well as taking a test to see how much you trust your gut feelings. In 1985, I was part of a police Emergency Response Team (ERT or SWAT for Americans). We were sent to the frozen wilds of the Canadian north to arrest an armed and murderous madman. Michael Oros, the bad guy, got the drop on my partner and me just as I had this incredible gut feeling that he’d silently crept up behind us. I spun around right as the fire-fight started. Because of this intuitive gut feeling—this overpowering presence of imminent danger—I was able to react to save my life and probably the lives of other teammates.

I didn’t imagine that gut feeling. It was as real as the keyboard I’m writing this on, and I have no explanation for it other than we, as human beings, are hard-wired to receive subconscious information through a process best known as intuition. Whether we use our gut feeling’s information or discard it is a matter of personal choice.

Gut feeling intuition has fascinated scientists and philosophers. It fascinates me, as well, and I don’t qualify as either a scientist or a philosopher. It’s not just people who have intuition and gut feelings. Why do dogs seem to know when their owners are coming home, and why do horses naturally understand what people to trust and what people to mistrust? Is it animal common sense?

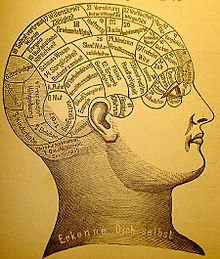

Surely there’s more to human intuition/gut feeling than common sense. Something else is at work here, and the philosophical theories go back as far as Plato. In his book Republic, Plato defined intuition as “a fundamental capacity for human reason to comprehend the true nature of reality—a pre-existing knowledge residing in the soul of eternity—truths not arrived at by reason but accessed using a knowledge already present in a dormant form and accessible to our intuitive capacity”. Plato called this concept anamnesis.

Surely there’s more to human intuition/gut feeling than common sense. Something else is at work here, and the philosophical theories go back as far as Plato. In his book Republic, Plato defined intuition as “a fundamental capacity for human reason to comprehend the true nature of reality—a pre-existing knowledge residing in the soul of eternity—truths not arrived at by reason but accessed using a knowledge already present in a dormant form and accessible to our intuitive capacity”. Plato called this concept anamnesis.

Ancient Eastern and old Western philosophers intertwined intuition with religion and spirituality. From Hinduism’s Vedic, we get two-fold reasoning for human gut feelings (mana in Sanskrit). First, is imprinting of psychological experiences constructed through sensory information—the mind seeking to become aware of the external world. Second, a natural action when the mind is aware of itself, resulting in humans being awareness of their existence and their environment.

In Buddhism, you’ll find a similar take on intuition. Monks teach that intuition is a faculty in the mind of immediate knowledge that’s beyond the mental process of conscious thinking, as conscious thought cannot necessarily access subconscious information or render such information into a communicable form. Gut feelings, according to Buddhism, are mental states immediately connecting the Universal Mind with your individual, discriminating mind.

More modern-day philosophers, like Descartes, say intuition is “pre-existing knowledge gained through rational reasoning or discovering truth through contemplation that manifests in subconscious messaging.” Descartes goes on to say, “Whatever I clearly and distinctly perceive to be true is true no matter if I see it subconsciously.”

Immanuel Kant offered this: “Intuition consists of basic sensory information provided by the cognitive faculty of sensibility equivalent to what loosely might be called perception through conscious and subconscious.”

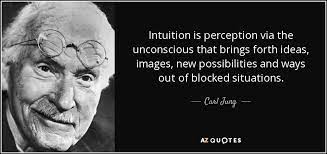

In Psychological Types written in 1916 by Carl Jung, you’ll read this: “Intuition is an irrational function, opposed most directly by sensation and less opposed strongly by the rational functions of thinking and feeling. Intuition is perception via the unconscious using sense-perception only as a starting point to bring forward ideas, images, possibilities, ways out of a blocked situation, by a process that is mostly unconscious.”

In Psychological Types written in 1916 by Carl Jung, you’ll read this: “Intuition is an irrational function, opposed most directly by sensation and less opposed strongly by the rational functions of thinking and feeling. Intuition is perception via the unconscious using sense-perception only as a starting point to bring forward ideas, images, possibilities, ways out of a blocked situation, by a process that is mostly unconscious.”

Freud—always the contrarian—called bullshit on Jung. Freud said, “Knowledge can only be attained through the conscious intellectual manipulation of carefully made observations. I reject any other means of acquiring knowledge such as intuition (gut feelings).”

That’s a short canvassing of philosophers. So, what do the scientists say about gut feelings?

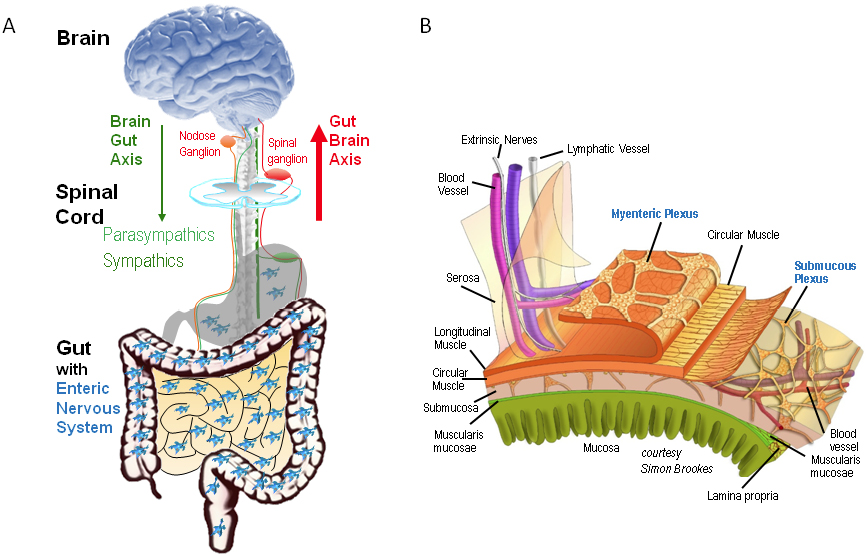

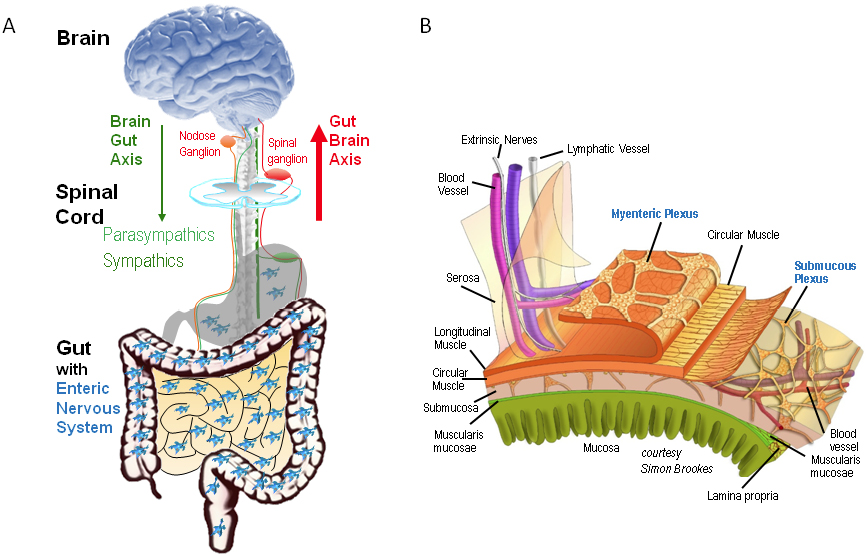

Well, neurologists have a lot to offer about how intuition is biologically tied into the gut. They say our gut, our gastrointestinal (GI) system, has an entire mind of its own called the Enteric Nervous System (ENS) that operates alongside, but independent of, our brain and Central Nervous System (CNS) functions. Our ENS is two layers of more than 100 million nerve cells lining the entire GI system from start to finish—from our esophagus to our anus, or from our yap to our hoop as a layperson might say.

This incredibly complex ENS has a full-time job of regulating our GI tract whose main purpose is to keep us alive through sustainable nutrition. Neurologists say the ENS acts on instinct and constantly exchanges information to our brain through our CNS. When the ENS senses something awry, it immediately alerts the brain that can choose to react consciously or subconsciously.

That works both ways. When the brain consciously or subconsciously alarms, it notifies the ENS which just might explain why you get that feeling in your stomach—that gut feeling. It’s why anxiety can bung you up or make you throw up. In the end, it might be diarrhea that ultimately lets you know to trust your gut feelings.

Okay, that explains the neuroscience behind the ENS gut feeling reaction. But it doesn’t explain what intuition is, and it’s probably worthwhile to look at a definition of intuition which seems to be a different process than a physical gut feeling. Here’s the best differentiating explanation I could find about instinct, gut feeling, and intuition.

Instinct — our innate inclination toward a particular behavior as opposed to a learned response.

Gut Feeling — a hunch or a sensation that appears quickly in consciousness (notable enough to be acted upon if one chooses) without us being fully aware of the underlying reasons for its occurrence.

Intuition — the process giving us the ability to know something directly without analytic reasoning, bridging the gap between the conscious and subconscious parts of our mind, and also between instinct and reason.

If I understand this correctly, gut feelings are short flashes of raw sensory alerts while intuition is a higher-evolved mechanism of subconsciously processing information without stopping to run reams of paper through the mental printer. So, my reasoning goes, intuition must be more of a learned behavior manufactured through experiences, both consciously built and subconsciously retained. Gut feelings, on the other hand, are more instinctive and primal.

I looked around for scientific studies on intuition and found credible works by Daniel Kahneman who won a Nobel Prize for his work on human judgment and decision-making. Without going into detail, Dr. Kahneman and his group conclusively proved there was a valid science behind human intuition which included—not surprisingly—gut feelings.

Another scientific study led by Dr. Gerd Gigerenzer of the Max Plank Institute for Human Development, agreed. Dr. Gigerenzer stated, “People rarely make decisions on the basis of reason alone, especially when the problems faced are complex. I think intuition’s merit has been vastly underappreciated as a form of unconscious intelligence.”

These intuition studies tie into works done by Dr. Gary Klein’s organization at the Natural Decision Making Movement who studied real-life decision processing by people in high-stress situations. They observed police officers, soldiers, paramedics, nurses, and fighter pilots coming to the conclusion that these professionals’ intuitive abilities developed from recognizing regularities, repetitions, and similarities between information available to them combined with their past experiences.

These intuition studies tie into works done by Dr. Gary Klein’s organization at the Natural Decision Making Movement who studied real-life decision processing by people in high-stress situations. They observed police officers, soldiers, paramedics, nurses, and fighter pilots coming to the conclusion that these professionals’ intuitive abilities developed from recognizing regularities, repetitions, and similarities between information available to them combined with their past experiences.

Out of their scientific work of studying intuitive reactions under stressful and challenging situations involving time pressure, uncertainty, unclear goals, and organizational restraints came a fighter pilot training model called the OODA Loop or the Circle of Competence. It’s a simple formula every high-performance jet jockey now memorizes to the point of being instinctive, intuitive, and gut-felt. It goes like this:

O — Observe

O — Orient

D — Decide

A — Act

So, is developed intuition, or its cruder form of visceral gut feeling, reliable? I’d say if it’s good enough to train fighter pilots with then it’s good enough for us. Let’s put it to the test.

I found a terribly non-scientific (but totally fun) click-bait site with a ten-question roll-through called the Queendom Gut Instinct Test. You can take it for a spin here:

https://www.queendom.com/queendom_tests/transfer

To score your results, you have to click the boxes at the site, but don’t worry—there’s no cost involved, and it’s an interesting self-perspective based on your gut reaction answers. These are the ten questions and multiple choice answers:

1. Did you ever get the sense that something was wrong or someone was in danger and ended up being right?

Yes ——— No ———

2. Do you believe that your gut instinct is at least as reliable as your rational mind?

Yes ——— No ———

3. Do you believe that a person can give off good or bad “vibes?”

Yes ——— No ———

4. You’re shopping with your partner for a new home. The real estate agent you’re working with pulls up to a beautiful house in the exact style you are looking for. However, when you walk through the front door, you are suddenly overcome with a sense of dread and foreboding. The place has a really creepy ambiance. What would you do?

A ——— Walk right back out. There is definitely something wrong with this place.

B ——— Ask the agent about the house’s history. If something bad happened here, I am not buying it.

C ——— Do a tour of the place, since I am here anyway. If I can’t shake the negative feeling AND there are major structural issues with the house, then I won’t buy it.

D ——— Shake it off. Even if something occurred, my partner and I will fill it with better memories.

F ——— Make an offer. Who cares about the house’s history? This is my dream home!

5. Two weeks before you’re about to go on a trip overseas, you have a recurring dream that the airplane you’re on needs to make an emergency landing due to a technical failure. What would you do?

A ——— Ignore it. It’s just a sign that I am nervous about flying.

B ——— Go on the trip, but say a few prayers or bring my lucky charm.

C ——— Reschedule my flight. There’s obviously a reason why I am having this dream every night.

6. Your friend introduces you to his or her new significant other. From the first conversation, you get the sense that there is something off about this person – like he/she is hiding something, or not being genuine. What would you do?

A ——— Dismiss it as paranoia. I barely know this person, so I have no right to judge him or her so quickly.

B ——— Put the feeling aside for now, but keep an eye out for suspicious behavior.

C ——— Try to probe a bit and/or do some research to see if there is something to my hunch.

D ——— Warn my friend to be careful and not to trust this person too quickly – my gut is never wrong.

7. Time to upgrade your wheels. How would you most likely approach this purchase?

A ——— I would conduct some research, weigh the pros and cons of different models, and then find a car that fits my needs and budget.

B ——— I would do some research on different models, then test drive the car to see how I feel in it.

C ——— I would have a general idea of what I want, but it would come down to one thing: if it’s the right car for me, I will know it when I’m in it.

8. You’re out buying coffee when you come across an old colleague who left the company to start his own business. He had a major fallout with management when he was turned down for a promotion. He says his startup is doing great, and he offers you a job on his team with a lucrative salary as well as benefits. It sounds like an amazing opportunity – but your gut is telling you to turn it down. What would you do?

A ——— Thank him for the offer, but decline. My gut is obviously picking up on something that he’s not telling me.

B ——— Ask him to give me some time to consider the offer, and then do some research on his company to see if it’s doing as well as he says it is.

C ——— Jump on the offer. There is no way I would turn down this amazing chance for a better job!

9. As you’re leaving your friend’s place and walking to your car, you hear a clear voice in your head say, “Don’t drive home. Stay here for the night.” You decide to listen and sleep over. The next morning, you find out that there was a fatal 8-car accident the night before – on the exact road you were planning to take, at the exact time you were about to leave. What would you most likely be thinking?

A ——— “Interesting coincidence.”

B ——— “That’s so strange. Maybe someone is looking out for me.”

C ——— “I am so grateful I listened to that warning in my head.”

10. You’re at a convenience store to pick up a lottery ticket. How do you choose your numbers?

A ——— I let the machine pick them at random.

B ——— I play the same numbers every time.

C ——— I pick the numbers based on what my gut tells me.

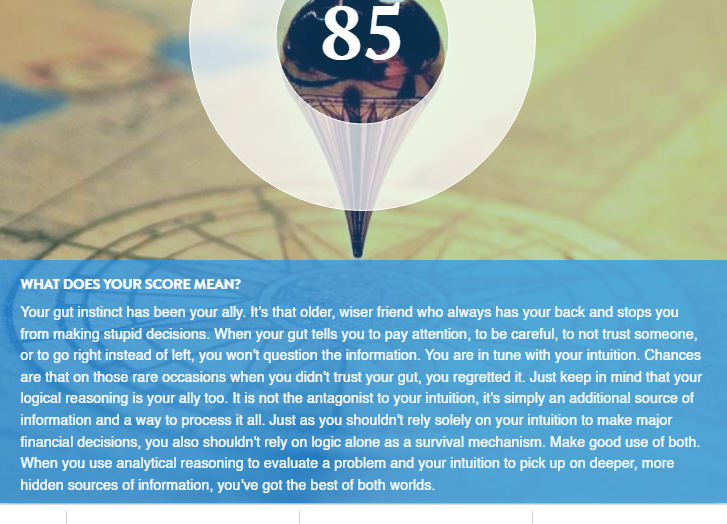

Again, you’ll have to take the test at its online site to get your Gut Instinct Score. How did I make out? I got an 85, and here’s what the site said about me:

Your gut instinct has been your ally. It’s that older, wiser friend who always has your back and stops you from making stupid decisions. When your gut tells you to pay attention, to be careful, to not trust someone, or to go right instead of left, you won’t question the information. You are in tune with your intuition. Chances are that on those rare occasions when you didn’t trust your gut, you regretted it. Just keep in mind that your logical reasoning is your ally too. It is not the antagonist to your intuition, it’s simply an additional source of information and a way to process it all. Just as you shouldn’t rely solely on your intuition to make major financial decisions, you also shouldn’t rely on logic alone as a survival mechanism. Make good use of both. When you use analytical reasoning to evaluate a problem and your intuition to pick up on deeper, more hidden sources of information, you’ve got the best of both worlds.

The Gut Instinct Test doesn’t tell you which questions you got “right or wrong”. I think there’s some sort of algorithmic scoring process that gives you a value which is why I got an 85 or an 8.5 out of 10. I know which one I bombed (for sure) and that was the lotto number thing. I always use the machine quick-pick because I’m too lazy to think it out for myself.

How about you DyingWords followers? Do you trust your gut feelings? And if you take the test, how about sharing your results?

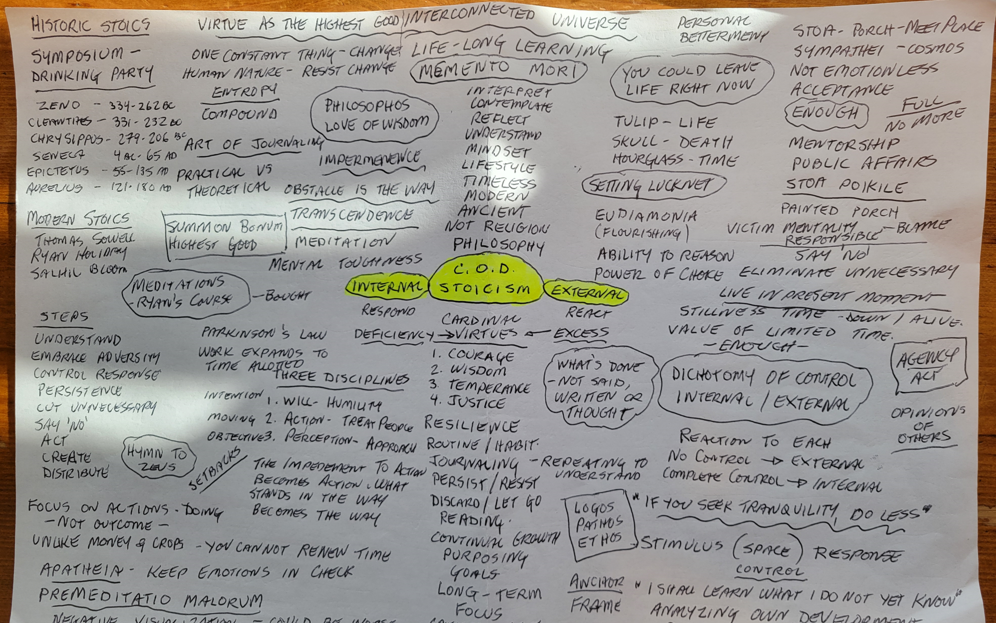

Memento Mori, translated from Latin, means “Remember, you must die”. It’s a wake-up that your life course could be radically altered and end at any moment. Our lives are impermanent, in constant flux and change, flowing through time towards entropy and inevitable death that might happen without warning. Memento Mori — You could leave life right now.

Memento Mori, translated from Latin, means “Remember, you must die”. It’s a wake-up that your life course could be radically altered and end at any moment. Our lives are impermanent, in constant flux and change, flowing through time towards entropy and inevitable death that might happen without warning. Memento Mori — You could leave life right now.

Everyone—you and me included—has heard their small inner voice speak. It might have been a muffled word of sage advice, a loud yell of urgent caution, or a simple suggestion towards the right move. Evolutionary, our subconscious source of wisdom has served us well

Everyone—you and me included—has heard their small inner voice speak. It might have been a muffled word of sage advice, a loud yell of urgent caution, or a simple suggestion towards the right move. Evolutionary, our subconscious source of wisdom has served us well Just a quick personal story before we move on to look at the philosophy, psychology, and physiology behind intuition as well as taking a test to see how much you trust your gut feelings. In 1985, I was part of a police Emergency Response Team (ERT or SWAT for Americans). We were sent to the frozen wilds of the Canadian north to arrest an armed and murderous madman. Michael Oros, the bad guy, got the drop on my partner and me just as I had this incredible gut feeling that he’d silently crept up behind us. I spun around right as the fire-fight started. Because of this intuitive gut feeling—this overpowering presence of imminent danger—I was able to react to save my life and probably the lives of other teammates.

Just a quick personal story before we move on to look at the philosophy, psychology, and physiology behind intuition as well as taking a test to see how much you trust your gut feelings. In 1985, I was part of a police Emergency Response Team (ERT or SWAT for Americans). We were sent to the frozen wilds of the Canadian north to arrest an armed and murderous madman. Michael Oros, the bad guy, got the drop on my partner and me just as I had this incredible gut feeling that he’d silently crept up behind us. I spun around right as the fire-fight started. Because of this intuitive gut feeling—this overpowering presence of imminent danger—I was able to react to save my life and probably the lives of other teammates. Surely there’s more to human intuition/gut feeling than common sense. Something else is at work here, and the philosophical theories go back as far as Plato. In his book Republic, Plato defined intuition as “a fundamental capacity for human reason to comprehend the true nature of reality—a pre-existing knowledge residing in the soul of eternity—truths not arrived at by reason but accessed using a knowledge already present in a dormant form and accessible to our intuitive capacity”. Plato called this concept anamnesis.

Surely there’s more to human intuition/gut feeling than common sense. Something else is at work here, and the philosophical theories go back as far as Plato. In his book Republic, Plato defined intuition as “a fundamental capacity for human reason to comprehend the true nature of reality—a pre-existing knowledge residing in the soul of eternity—truths not arrived at by reason but accessed using a knowledge already present in a dormant form and accessible to our intuitive capacity”. Plato called this concept anamnesis. In Psychological Types written in 1916 by Carl Jung, you’ll read this: “Intuition is an irrational function, opposed most directly by sensation and less opposed strongly by the rational functions of thinking and feeling. Intuition is perception via the unconscious using sense-perception only as a starting point to bring forward ideas, images, possibilities, ways out of a blocked situation, by a process that is mostly unconscious.”

In Psychological Types written in 1916 by Carl Jung, you’ll read this: “Intuition is an irrational function, opposed most directly by sensation and less opposed strongly by the rational functions of thinking and feeling. Intuition is perception via the unconscious using sense-perception only as a starting point to bring forward ideas, images, possibilities, ways out of a blocked situation, by a process that is mostly unconscious.”

These intuition studies tie into works done by Dr. Gary Klein’s organization at the Natural Decision Making Movement who studied real-life decision processing by people in high-stress situations. They observed police officers, soldiers, paramedics, nurses, and fighter pilots coming to the conclusion that these professionals’ intuitive abilities developed from recognizing regularities, repetitions, and similarities between information available to them combined with their past experiences.

These intuition studies tie into works done by Dr. Gary Klein’s organization at the Natural Decision Making Movement who studied real-life decision processing by people in high-stress situations. They observed police officers, soldiers, paramedics, nurses, and fighter pilots coming to the conclusion that these professionals’ intuitive abilities developed from recognizing regularities, repetitions, and similarities between information available to them combined with their past experiences.