This Halloween, the witch isn’t green with a long, warty nose. She doesn’t have a tall pointy hat, a sneering black cat, or a magical flying broom. She doesn’t cast spells with eye of newt, smidge of hemlock, and sting of nettle, nor inflicts mean, mean pain on waif-like kids. No, today’s witch is digital. She’s connected, socially smart, and sorcery savvy.

This Halloween, the witch isn’t green with a long, warty nose. She doesn’t have a tall pointy hat, a sneering black cat, or a magical flying broom. She doesn’t cast spells with eye of newt, smidge of hemlock, and sting of nettle, nor inflicts mean, mean pain on waif-like kids. No, today’s witch is digital. She’s connected, socially smart, and sorcery savvy.

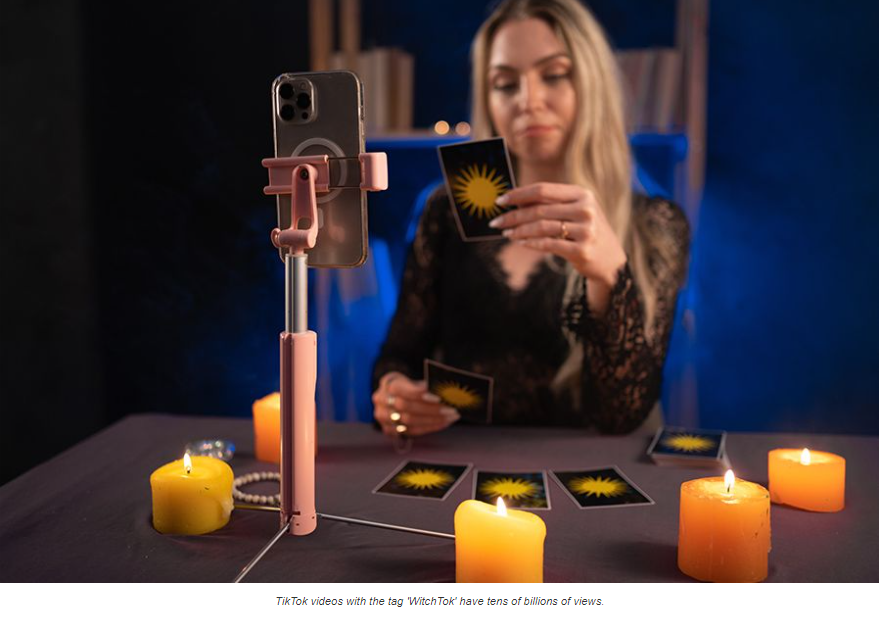

Wicca online has explosively grown in the past few years. Especially since the Covid lockdowns forced secluded young women to seek novel friendships through social media. The appeal of the occult—the mystic and arcane—mesmerized millions and millions who tuned to #WitchTok, a platform now having 42 billion views. Yes, 42 billion. Witchcraft is just that popular.

It’s a fascinating shift in society with practicing Wiccans doing digital covens. And it’s far from the witches of Macbeth, Salem, Oz, and Samantha. Let’s look at what #WitchTok is and how the explosive growth of Wicca online came about.

In Dyingwords posts, I usually create new, from-scratch content about subjects I have some expertise in like human death investigation or writing and publishing. Today, I’m talking witches—witch talking—something I have absolutely no experience with except that the editor of my first novel, No Witnesses To Nothing, was a practicing Wiccan. I found her very intelligent, and there was nothing kooky or spooky about Heather at all.

For this piece, I’ll defer to the real experts—witches I’ve sourced online and extracted quotes from. It’s far better to hear from those in the know, especially about a topic like witchcraft which I suspect is poorly understood by the rank and file. However, we need to know the background of Wicca, Wiccan, and witchcraft. For that, I’m turning to my AI friend.

Me — Please explain clearly and in detail what Wicca is. Give me the history, how it progressed, and what the status of Wicca is today.

Friend — Wicca is a modern pagan, witchcraft religion that was developed in England during the first half of the 20th century. Though influenced by pre-Christian beliefs and practices of Europe, it is distinct from these as a specific, organized path with its own unique characteristics. Gerald Gardner, a British civil servant and amateur anthropologist, is credited with founding what is now known as Wicca in the 1940s.

History and Development — Early Foundations

The roots of Wicca trace back to the early 20th century with the resurgence of interest in esotericism and the occult in Europe. Figures like Aleister Crowley and organizations like the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn were part of this broader milieu that influenced Gerald Gardner.

Gerald Gardner and Wicca’s Formation

Gardner was initiated into a New Forest coven in the late 1930s or early 1940s and claimed that this coven was a surviving part of an ancient witchcraft tradition. However, historical accuracy of these claims remains contested. In the 1950s, Gardner began publicizing his beliefs and practices through books and lectures, calling it “Witchcraft” and later “Wicca,” which he claimed was derived from Old English meaning ‘the wise ones.’

Spread and Evolution

After the Witchcraft Act was repealed in England in 1951, Gardner published more openly about his beliefs and practices. His works, notably “Witchcraft Today” (1954) and “The Meaning of Witchcraft” (1959), served as foundational texts for Wicca. In the 1960s and 1970s, Wicca spread rapidly in the United States and Canada, largely due to the influence of figures like Raymond Buckland, who introduced what became known as the Gardnerian Wicca tradition.

Beliefs and Practices

Wicca is diverse, with no central authority, but it typically includes the worship of a Goddess and a God; the observance of seasonal festivals known as Sabbats, which make up the Wheel of the Year; and esbat rituals held at the full moon. Wiccans practice magic, often aligned with natural forces, and adhere to a moral code known as the Wiccan Rede, which states “An it harm none, do what ye will.”

Contemporary Wicca

Today, Wicca has evolved into a variety of traditions, some closely following Gardnerian practices, while others have developed new interpretations or amalgamated practices from other spiritual paths. It is recognized as an official religion in some countries, with practitioners entitled to the same rights and protections as followers of other religions.

Modern Diversity

Contemporary Wicca includes a variety of traditions such as Alexandrian, Dianic, and Seax-Wica, among others. There’s also a trend toward more eclectic and solitary practitioners, who blend Wiccan practices with other spiritual beliefs.

Challenges and Acceptance

While Wicca has gained greater acceptance as a legitimate religion, practitioners can still face misconceptions and prejudice. However, its ecological ethos and reverence for nature align closely with contemporary ecological concerns, adding to its appeal.

Online and Global Spread

The internet has played a significant role in the spread and evolution of Wicca. Online forums, social media, and digital covens have made it easier for solitary practitioners to learn about Wicca, connect with others, and practice rituals even in remote areas.

Wicca continues to adapt and evolve, influenced by broader cultural shifts and the needs of its practitioners. It remains a dynamic and growing religious movement that appeals to many seeking a more personal, nature-based, or feminist spirituality.

Me — What is Wiccan?

Friend — “Wiccan” refers to an adherent of Wicca, a modern pagan and witchcraft religion. It can be used both as a noun and an adjective. As a noun, a Wiccan is someone who practices Wicca, embracing its rituals, beliefs, and ethical codes. As an adjective, “Wiccan” describes anything related to the Wicca religion, such as Wiccan rituals, Wiccan beliefs, or Wiccan practices.

Key Aspects of Being Wiccan:

- Beliefs: Wiccans typically believe in a dual deity, worshipping both a Goddess and a God, who represent various forms of nature and aspects of life. They may also believe in other spiritual entities such as spirits, ancestors, or other deities.

- Practices: Wiccan practices include ritual magic, casting circles for protection during rituals, celebrating seasonal festivals known as Sabbats (which honor the cycles of nature), and performing rites at phases of the moon, known as Esbats.

- Ethics: Wiccans generally follow the Wiccan Rede, an ethical guideline that states “An it harm none, do what ye will.” This underscores a philosophy of freedom and responsibility, emphasizing that one’s actions should not intentionally harm others.

- Community and Solitary Practice: While many Wiccans join covens, which are formal groups with initiated members who gather for rituals, many others practice alone as solitary Wiccans. Solitary practice allows individuals to adapt rituals and beliefs to their personal spiritual needs.

Wiccans often feel a deep connection to nature, seeing the divine manifest in the world around them. This connection guides their practices and rituals, many of which are geared towards aligning with natural forces and cycles.

Me — What is a witch?

Friend — A “witch” is a term with a complex and varied history, and its meaning can differ significantly depending on cultural, historical, and individual contexts. Broadly, a witch is someone who practices witchcraft—a set of skills and knowledge that often involves magic, ritual, and an understanding of natural forces. Here are a few key perspectives on what a witch typically represents:

Historical Perspective

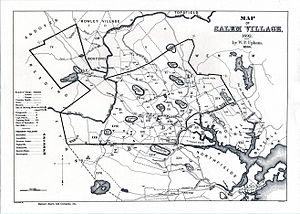

Historically, the concept of a witch has often been associated with negative stereotypes and misconceptions. In many cultures, witches were thought to be individuals who used supernatural powers to cause harm. This view was particularly prominent during the witch trials in Europe and North America from the 15th to 18th centuries, where many accused witches were persecuted.

Modern Neopagan Perspective

In modern times, particularly within Neopagan religions like Wicca, being a witch is viewed positively. Witches in these contexts are practitioners of witchcraft who engage in rituals, cast spells, and work with the energies of nature to bring about change. These practices are often aimed at healing, protection, and personal growth, rather than harm.

Cultural Variations

The definition of a witch can vary widely across different cultures:

- In African and Afro-Caribbean traditions, such as those practiced in Voodoo, Santería, and other religions, witches may have roles that blend magical practices with community healing.

- In European folklore, witches were often seen as wise women or men who understood herbs, could heal the sick, and had the ability to affect change through supernatural means.

- In indigenous cultures, the concept similar to witches might involve shamanic practices, where certain individuals interact with the spirit world for healing or guidance.

Characteristics of Witches

- Magic and Ritual: Witches often use rituals and magic to work with natural energies to manifest changes. This can involve casting spells, using tarot cards, practicing divination, and creating potions or herbal remedies.

- Connection to Nature: Many witches feel a deep connection to nature and often honor the earth and its seasons through various ceremonies and rituals.

- Ethical Considerations: Ethical practices can vary, but many witches follow a form of the ethical guideline, such as “Harm none,” which emphasizes the importance of not causing harm to others with one’s actions.

In Popular Culture

In literature, film, and television, witches have been portrayed in a variety of ways, from the wicked witches in fairy tales like “Hansel and Gretel” and “The Wizard of Oz” to more sympathetic figures in modern media like “Harry Potter” or “The Craft.” These portrayals can influence how the general public perceives witches.

Overall, being a witch involves a diverse range of beliefs and practices, and its interpretation can change dramatically depending on the cultural and religious context. The modern appreciation for witches and witchcraft generally focuses on empowerment, the reclaiming of personal and communal power, and a profound respect for nature and its cycles.

Me — What is witchcraft?

Friend — Witchcraft is a complex, multifaceted practice with various meanings and interpretations, depending on cultural, historical, and individual contexts. Generally, it refers to the use of magical or supernatural powers and practices that involve rituals, spells, and an understanding of natural forces. Here are some key aspects that define witchcraft:

Historical and Cultural Contexts

- Pre-modern Witchcraft: In many pre-modern societies, witchcraft was viewed with suspicion and fear, often associated with malevolent magic used to harm others. This perspective was especially prevalent in Europe during the Middle Ages and the early modern period, where it led to witch hunts and trials.

- Indigenous Practices: In various indigenous cultures, practices that might be considered witchcraft in Western terms are often part of shamanistic traditions, involving healers or spiritual leaders who interact with the spirit world for the benefit of their community.

- African and Afro-Diasporic Traditions: In African and Afro-Caribbean contexts, such as in Voodoo, Santería, and Candomblé, witchcraft can involve complex systems of magic, healing, and interaction with spirits or ancestors, often serving protective or healing roles within the community.

Modern Witchcraft

- Neopagan Witchcraft: In contemporary contexts, particularly within Neopagan movements like Wicca, witchcraft is seen in a positive light. It involves practices intended to work with natural energies to effect change, often focused on personal growth, healing, and positive transformation.

- Eclectic Witchcraft: Many modern practitioners of witchcraft draw on a variety of traditions and may not adhere to a single religious framework. These eclectic witches blend elements from different spiritual and magical systems based on personal beliefs and experiences.

Practices and Beliefs

- Magic and Rituals: Witchcraft involves various magical practices, including spell-casting, divination (like tarot reading), herbalism, and the crafting of magical objects. Rituals can be complex ceremonies or simple personal practices intended to manifest specific changes or desires.

- Connection to Nature: A significant aspect of witchcraft is its emphasis on the natural world and its cycles. Many witches celebrate seasonal festivals that honor these cycles, such as the solstices and equinoxes.

- Deities and Spirits: Some witches work with deities or spiritual entities. In traditions like Wicca, these might include a God and Goddess. Others may connect with a broader range of spirits or ancestral figures.

- Ethical Considerations: Ethical views in witchcraft vary, but many follow some form of the Wiccan Rede, “An it harm none, do what ye will,” which emphasizes the importance of not harming others through one’s magical practices.

Social and Cultural Impact

Witchcraft has been reevaluated in many contemporary societies, moving from a stigmatized and persecuted practice to one that is increasingly accepted and embraced, especially within alternative spiritual communities. It is often seen as a means of empowerment, a way to reclaim agency, and a path to deeper understanding and connection with the world.

In popular culture, witchcraft continues to captivate the imagination, depicted in a wide array of narratives from horror to fantasy, reflecting both historical fears and modern reimaginings of the witch as a figure of power and mystery.

Me — What is #WitchTok and how many views has it had?

Friend — #WitchTok is a popular hashtag on TikTok that encompasses videos related to witchcraft and magical practices. As of now, October 2024, it has amassed over 42 billion views. This online community involves content ranging from tarot readings and crystal usage to candle-burning rituals and advice for newcomers interested in witchcraft. The significant viewership reflects a broad interest in magical and mystical themes on social media platforms.

Me — That’s a lot of views. Now let’s hear from the witches themselves.

Ayla Skinner created #WitchTok. She says, “For Wiccans and witches, magic is real. They believe that magic happens when psychic energy is raised through dance, song, rituals, or meditation. It’s then directed through thought into a particular outcome. All living beings produce psychic energy that can be used to change things in the world. Those who are trained, such as witches, can do it more often and with more accuracy. For many, Wicca is a form of spirituality that provides a sense of community. #WitchTok is a community that gives you a bit of control in your life.”

Helen Berger says, “Wicca began to be practiced by American feminists in the 1960s and was underground. By 2000, with the arrival of online communities and the decline in affiliation with traditional religions, witchcraft began its entry into the mainstream. While Wicca is a religion, it’s individualistic in many ways. You can do your own thing. It’s not signing on to an institutional dogmatic organization. It’s not signing on to a set of actions or beliefs that you must adhere to.”

Berger continues, “Witchcraft reflects two timeless and universal urges. The need to draw meaning from chaos, and the desire to control the circumstances around us. It’s the connection between energy, objects, and people where the magic is. Look at quantum entanglement which proves that objects can influence each other instantaneously in unforeseen ways and at great distances. Isn’t that magic?”

Emma Griffin is an A-list author. “The rise of platforms like TikTok and Instagram played a significant role in making witchcraft more visible and accessible. This is a very positive development and very beneficial especially for younger, marginalized women. However, it’s crucial to approach the practice of witchcraft with respect and awareness of the origins and the meanings.”

Kemi Mani is a witch with over 300,000 X followers. “It brings people to a new awareness. People can become interested in witchcraft and can dabble in it to see if it’s for them. Or not. When you’re alone in your house, and you don’t have many people to connect with and the only thing you’re craving is a connection—that’s what people find in these spiritual spaces like #WitchTok. Connection. Something beyond the material.”

This from Julie Roys. “It makes sense that witchcraft and the occult would rise as society becomes increasingly postmodern. The rejection of Christianity has left a void that people, inherently spiritual beings, will seek to fill. Wicca has effectively repackaged witchcraft for millennial consumption. No longer is witchcraft and paganism satanic and demonic. It’s a pre-Christian tradition that promotes free thought and understanding of the earth and of nature.”

Honey Rose goes by the handle @thathoneywitch. Her quote is, “I am a lot of marginalized groups. I’m nonbinary. I’m queer. I’m half-black. I practice magic and that has been the voice of people who are voiceless, and it has been for a very long time. Some people have a problem with traditional religions and traditional spirituality so sometimes they go towards an abstract form of spirituality which can be witchcraft.”

Gabriela Herstik is the author of Inner Witch: A Modern Guide to the Ancient Craft. Gabriela offers, “We live in a very dark intense age. People want purpose, and they want connection. But beyond that, they want something that helps them connect to something larger than themselves. Something that helps them feel like there’s a purpose, and witchcraft does that. Magic is a way to align with your purpose, your power.”

And Diana Rose (no relation to Honey Rose) sums it up. “It’s engaging outside the boundaries of scientific materialism. We all have a desire to reach out and connect with each other and touch parts of our existence that can’t be understood or controlled by science. Through new channels like #WitchTok, these old ideas are providing people ways to start conversations and engage socially with introspection. A positive power in doing something—anything—to make sense of it all.”