Now that the balloon has popped on failed fads like Dot.Coms, Bored Ape NFTs, Crypto, and forever-free borrowed money, the world’s current FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out) has turned to the newest and coolest cat—Artificial Intelligence or what’s simply called AI. Make no mistake, AI is real. It’s not simple, but it’s very, very real. And it has the potential to be unbelievably good or gut-wrenchingly awful. But as smart as AI gets, will it ever be a match for Non-Artificial Intelligence, NAI?

Now that the balloon has popped on failed fads like Dot.Coms, Bored Ape NFTs, Crypto, and forever-free borrowed money, the world’s current FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out) has turned to the newest and coolest cat—Artificial Intelligence or what’s simply called AI. Make no mistake, AI is real. It’s not simple, but it’s very, very real. And it has the potential to be unbelievably good or gut-wrenchingly awful. But as smart as AI gets, will it ever be a match for Non-Artificial Intelligence, NAI?

I can’t explain what NAI is. I just have faith that it exists and has been a driving force in my life, especially my current life where I’m absorbed in a world of imagination and creativity. Call it make-believe or living in a dream, if you will, but I’m having a blast with a current fiction, content-creation project which uses both AI and NAI.

I’ve asked a lot of folks—mainly writing folks because that’s who I hang with—what their source of inspiration is. Their muse or their guide to the information pool they tap into to come up with originality. Many casually say, “God.”

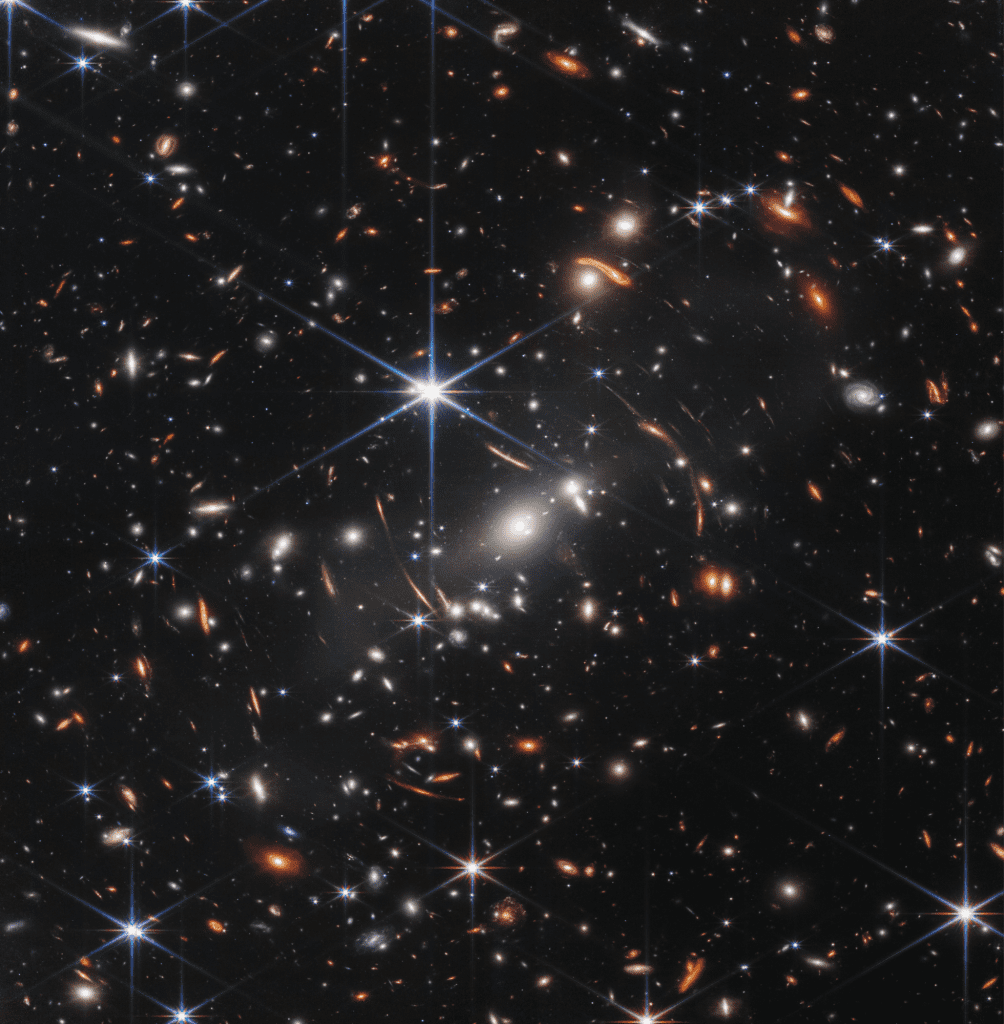

I don’t have a problem with the concept of God. I’ve been alive for 66 years and, to me, I’ve seen pretty strong evidence of an infinite intelligence source that created all this, including myself. I’ll call that force NAI for lack of a better term.

What got me going on this AI/NAI piece was three months of intensive research into the current state of artificial intelligence—what it is, how to use it, and where it’s going. AI is not only a central character in my series titled City Of Danger, AI is a tool I’m using to help create the project. I’m also using Non-Artificial Intelligence as the inspiration, the imagination, and the drive to produce the content.

If you’ve been following DyingWords for a while, you’re probably aware I haven’t published any books in the past two years except for one about the new AI tool called ChatGPT. That’s because I’m totally immersed in creating City Of Danger in agreement with a netstream provider and a cutting-edge, AI audio/visual production company. Here’s how it works:

If you’ve been following DyingWords for a while, you’re probably aware I haven’t published any books in the past two years except for one about the new AI tool called ChatGPT. That’s because I’m totally immersed in creating City Of Danger in agreement with a netstream provider and a cutting-edge, AI audio/visual production company. Here’s how it works:

I use my imagination to create the storyline (plot), develop the characters and their dialogue, construct the scenes, and set the overtone as well as the subtext theme. I use NAI for inspirational ideas and then feed all this to an AI audio/visual bot who scans real people to build avatars and threads them through a “filter” so the City Of Danger end-product looks like a living graphic novel.

Basically, I’m writing a script or a blueprint so an AI program can take over and give it life. The AI company does the film work and the netstream guy foots the bill. This is the logline for City Of Danger:

A modern city in existential crisis caused by malevolent artificial intelligence enlists two private detectives from its 1920s past for an impossible task: Dispense street justice and restore social order.

Here’s a link to my DyingWords web page on City Of Danger along with the opening scene of the pilot episode. Yes, it involves time travel and dystopian tropes which have been done to death—but not quite like this. I like to think of myself as the next JK Rowling except I’m not broke and don’t write in coffee shops with a stroller alongside.

I was going to do this post as a detailed dive into the current state of artificial intelligence and where this fascinating, yet intimidating, technology is going. However, I have a long way to go yet in my R&D and don’t have a complete grasp on the subject. I will give a quick rundown, though, on what I’ve come to understand.

The term (concept) of artificial intelligence has been around a long time. Alan Turing, the father of modern-day computing and its morph into AI, conceived a universal thinking machine back in WW2 when he cracked Nazi communication codes. In 1956, a group of leading minds gathered at Dorchester University where, for three months, they brainstormed and laid the foundation for future AI breakthroughs.

Fast forward to 2023 and we have ChatGPT version 4 and a serious, if not uncontrollable, AI race between the big hitters—Microsoft and Google. Where this is going is anyone’s guess and recently other big guns like Musk, Gates, and Wozniak weighed in, penning an open letter to the AI industry to cool their jets and take the summer off. To quote Elon Musk, “Mark my words, AI is far more dangerous (to humanity) than nukes.”

There’s huge progress happening in AI development right now. But stop and look around at how much AI has already affected your life. Your smartphone and smartTV. Fitbit. GPS. Amazon recommends. Siri and what’s-her-name. Autocorrect. Grammarly. Cruise missiles, car parts, and crock pots.

Each day something new is mentioned. In fact, it’s impossible to scroll through a newsfeed with the AI word showing up. We’re in an AI revolution—likely the Fourth Industrial Revolution to steal the phrase from Klaus Schwab and his World Economic Forum.

Speaking of an AI revolution, one of the clearest runs at explaining AI in layman’s terms is a lengthy post written and illustrated by Tim Urban. It’s a two-part piece titled The AI Revolution: Our Immortality or Extinction. Tim calls AI “God in a Box”. Here’s what ChatGPT had to say about it.

Tim Urban’s two-part post “The AI Revolution: Our Immortality or Extinction” explores the potential impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on humanity.

In part one, Urban describes the current state of AI, including its rapid progress and the various forms it can take. He also discusses the potential benefits and risks of advanced AI, including the possibility of creating a “superintelligence” that could surpass human intelligence and potentially pose an existential threat to humanity.

In part two, Urban delves deeper into the potential risks of advanced AI and explores various strategies for mitigating those risks. He suggests that developing “friendly AI” that shares human values and goals could be a key solution, along with establishing international regulations and governance to ensure the safe development and use of AI.

Overall, Urban’s post highlights the need for thoughtful consideration and planning as we continue to develop and integrate AI into our lives, in order to ensure a positive outcome for humanity.

From what I understand, there are three AI phases:

- Narrow or weak artificial intelligence—where the AI system only focuses on one issue.

- General artificial intelligence—where the AI system is interactive and equal to humans.

- Super artificial intelligence—where the AI system is self-aware and reproducing itself.

We’re in the narrow or weak phase now. How long before we reach phase two and three? There’s a lot of speculation out there by some highly qualified people, and their conclusions range from right away to never. That’s a lot of wriggle room, but the best parentheses I can put on the figure is 2030 for phase two and 2040 for phase three. Give or take a lot.

The AI technology involved in City Of Danger is a mid-range, phase one product. The teccie I’m talking to feels it’ll be at least 2025 before it’s perfected enough to have the series released. I think it’s more like 2026 or 2027, but that’s okay because it gives me more time to tap into NAI for more imaginative and creative storyline ideas.

I’m not going to go further into Narrow AI, General AI, or Super AI in this post. I’d have to get into terms like machine learning, large language model, neural networks, computing interface, intelligence amplification, recursive self-improvement, nanotech and biotech, breeding cycle, opaque algorithms, scaffolding, goal-directed behavior, law of accelerating returns, exponentiality, fault trees, Boolean function and logic gates, GRIND, aligned, non-aligned, balance beam, tripwire, takeoff, intelligence explosion, and that dreaded moment—the singularity. Honestly, I don’t fully understand most of this stuff.

But what I am going to leave you with is something I wrote about ten years ago when I started this DyingWords blog. It’s a post titled STEMI—Five Known Realities of the Universe. Looking back, maybe I nailed what Non-Artificial Intelligence really is.