“The pace of progress in artificial intelligence is incredibly fast. Unless you have direct exposure to groups like DeepThink and OpenAI, you have no idea how fast. It’s growing at an exponential pace. The risk of something seriously dangerous happening is in the five-year timeline. Ten years at the most. I am close—really close—to the cutting edge in AI, and it scares the hell out of me. It’s capable of vastly more than anyone knows, and the rate of improvement is beyond enormous. Mark my words. AI is far more dangerous to humans than nukes.” ~Elon Musk, uber-billionaire founder of SpaceX, Tesla, and leading investor in AI companies DeepThink and OpenAI.

“The pace of progress in artificial intelligence is incredibly fast. Unless you have direct exposure to groups like DeepThink and OpenAI, you have no idea how fast. It’s growing at an exponential pace. The risk of something seriously dangerous happening is in the five-year timeline. Ten years at the most. I am close—really close—to the cutting edge in AI, and it scares the hell out of me. It’s capable of vastly more than anyone knows, and the rate of improvement is beyond enormous. Mark my words. AI is far more dangerous to humans than nukes.” ~Elon Musk, uber-billionaire founder of SpaceX, Tesla, and leading investor in AI companies DeepThink and OpenAI.

Artificial intelligence isn’t a thing of the future. Not some grand vision of twenty-second-century technology. It’s here. Right now, I’m using AI to write this piece. My PC is a brand new HP laptop with Windows 11 backed by the latest Word auto-suggest and a Grammarly Premium editing app. My research flows through Google Chrome, and I have an AI search bar that (creepy) seems to know exactly what I’m thinking and wanting next. This is also the first post I’m experimenting with by plugging into an AI text-to-speech program for an audio version of this site.

AI is great for what I do—create content for the entertainment industry—and I have no plans to use AI for world domination. Not like a character I’m basing-on for my new series titled City Of Danger. It’s a work in progress set for release this fall—2022.

I didn’t invent the character. I didn’t have to because he exists in real life, and he’s a mover and shaker behind many world economic and technological advances including promoting artificial intelligence. His name is Klaus Schwab.

Who is Klaus Schwab? He’s the megalomanic founder and executive chairman of the World Economic Forum which is a left-leaning, think tank operated out of Davos, Switzerland. Since 1971, Klaus Schwab has amalgamated a unity among the Wokes—billionaires, heads of state, religious leaders, and royalty to convene in Davos and hammer out a new world order. I couldn’t have built a more diabolical villain if I had access to all the AI in the world and an organic 3D printer.

I’m not making this up. And it’s not a whacko conspiracy theory. Check out the World Economic Forum for yourself. Go deep. You’ll see they speak openly about their new world order based on their Stakeholder Capitalism principle designed for their Fourth Industrial Revolution. My take—the participating billionaires aren’t sucked in. They’re turning old school communism into neo-capitalist profit centers to which Klaus Schwab promotes by motivating the ultra-fat-cats and facilitating their network. Part of this grand scheme is using the creative power of artificial intelligence for realignment of the global economy. Redistribution of wealth—more for them and less for us.

What’s in it for Klaus Schwab to promote artificial intelligence as part of his new world order? Well, Klaus Schwab is 83 and he’s wearing out. Klaus Schwab is fascinated with artificial intelligence which is a founding principle behind transhumanism. He fervently believes humans can meld with AI machines and extend all capabilities including life spans. It’s entirely in Klaus Schwab’s interest to fast-track AI development if he wants to live long enough to wear his Master-Of-The-Universe jacket in public.

Here’s a quote from Klaus Schwab (Thick German accent):

“In the new world order of the fourth industrial revolution, you will rent what you need from the government. You shall own nothing, and you will be happy.”

Setting Klaus Schwab aside, there’s something else going on in the world’s order involving AI. Here’s a quote from Russian President Vladimir Putin:

“Artificial intelligence is the future, not only for Russia, but for all humankind. It comes with enormous opportunities, but also threats that are difficult to predict. Whoever becomes the leader in this sphere will become ruler of the world.”

A bit of AI trivia. Ukraine has a world-class, artificial intelligence tech industry. Some of the best and brightest AI designers work in Kyiv which is now under siege by Putin’s military. There are 156 registered AI firms in Ukraine and 8 universities specializing in AI research and teaching. The Ukrainian AI industry includes the finest, most advanced blockchain and cryptography technology anywhere on the planet as well as being a frontline in the development of autonomous AI weapons systems.

——

Before looking at just how dangerous AI is to human order, let’s take a quick look at what AI actually is.

Artificial Intelligence uses computers to do things traditionally requiring human intelligence. This means creating algorithms to classify, analyze, and draw predictions from collected data. It also involves acting on that collected data, learning from data, and improving over time. It’s like a child growing up to be a (sometimes) smarter adult. Like humans, AI is not perfect. Yet.

Artificial Intelligence uses computers to do things traditionally requiring human intelligence. This means creating algorithms to classify, analyze, and draw predictions from collected data. It also involves acting on that collected data, learning from data, and improving over time. It’s like a child growing up to be a (sometimes) smarter adult. Like humans, AI is not perfect. Yet.

AI has two paths. One is narrow AI where coders write specific instructions, or algorithms, into computer software for specific tasks. Narrow AI has fixed algorithms which cannot evolve into more advanced AI systems. General AI is more advanced. It’s specifically designed to learn from itself, teach itself new ideas, and invent stuff we’ve never dreamed possible.

General AI is the guy you gotta be scared of. Here’s a 1951 quote from Alan Turing, widely regarded as the father of modern computerism:

“Let us assume these smart machines are a genuine possibility, which I believe they are, and look at the consequences of constructing them. There would be plenty to do in keeping one’s intelligence up to the standards set by the machines, for it seems that once the machine thinking method had started, it would not be long for them to outstrip our feeble powers. At some stage, we would have to expect the machines to take control.”

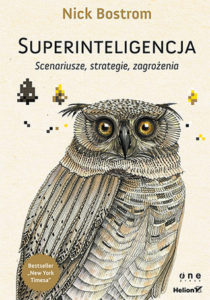

In rabbit-holing (aka researching) this piece, I read a few books. One, of course, was Klaus Schwab’s The Fourth Industrial Revolution. It’s a must if you want to get inside this guy’s head. Another was Davos Man—How the Billionaires Devoured the World by Peter S. Goodman. This is a fascinating look at how Klaus Schwab has organized mega-money to change the world’s governance and economic structures to which AI plays a big part. Then there’s Superintelligence—Paths, Dangers, Strategies by Nick Bostrom.

In rabbit-holing (aka researching) this piece, I read a few books. One, of course, was Klaus Schwab’s The Fourth Industrial Revolution. It’s a must if you want to get inside this guy’s head. Another was Davos Man—How the Billionaires Devoured the World by Peter S. Goodman. This is a fascinating look at how Klaus Schwab has organized mega-money to change the world’s governance and economic structures to which AI plays a big part. Then there’s Superintelligence—Paths, Dangers, Strategies by Nick Bostrom.

Here’s a take-away quote from Nick Bostrom in Superintelligence:

“Once unfriendly superintelligence exists, it would prevent us from replacing it or changing its preferences. Our fate would be sealed“.

Therein lies the general AI danger. Like all human creations, it’ll be fine they said until something goes wrong. Once a malicious AI manipulator allows an AI computer program to go rogue, our fate would be sealed. It would be impossible to put the digital genie back in the bottle. Here are the main perils possible with general AI, rogue or not:

Automation-Spurred Job Losses

AI overseers view employment realignment as the first general AI concern. It’s no longer a matter of if jobs will be lost. It’s already occurring, and the question is how many more will fall. The Bookings Institute estimates that 36 million Americans work in jobs that have high exposure to job automation where 70 percent of their tasks can be done cheaper and more efficiently by AI-programmed machines, Smart robots, if you will.

AI overseers view employment realignment as the first general AI concern. It’s no longer a matter of if jobs will be lost. It’s already occurring, and the question is how many more will fall. The Bookings Institute estimates that 36 million Americans work in jobs that have high exposure to job automation where 70 percent of their tasks can be done cheaper and more efficiently by AI-programmed machines, Smart robots, if you will.

Not all threatened workers are blue-collar by any means. White-collar guys and gals earning $100K per year can be replaced by AI. Think of the savings where a $200K software program can take over for 10 execs. That’d be an $800K/yr saving, and the boss would be perfectly within their legal rights to fire them. Would the boss feel bad about it? Probably, but AI wouldn’t care.

Privacy, Security, and the Rise of Deepfakes

Look at China if you want to see AI in action. The Chinese government has hundreds of millions of networked surveillance cameras watching their citizens. Data mining includes individual habits such as travel, consumer purchases, entertainment choices, political views expressed by social media or online searches, and even walking characteristics let alone facial recognition. Part of the security-over-privacy design of China’s AI Big Brother is making a social credit profile of its 1.4 billion people. The better your score (behavior) the better your life.

Deepfakes are terrifying possibilities. This is a drill down on fake news where AI constructs a completely convincing facsimile of a person for fraudulent use. Forget about raiding a bank account using an AI-simulated profile or an AI scammed IRS phone call. Think of a world leader like a president during election time when a fake AI image of them publicly performs an act so reprehensible that it costs them the office. Or supporting a dictator. Whose lies would you believe?

Stock Market Instability Caused by Algorithmic High-Frequency Trading

This has already happened. In 2010, the Flash Crash took the Dow Jones down by 1,000 instantaneously costing the marketplace over $1 trillion. It was caused by a manipulator who short-stocked a trade that the algorithmic high-frequency took to be a market upset. The computers took over and instantly sold off private stocks in a hyper-dumping.

This has already happened. In 2010, the Flash Crash took the Dow Jones down by 1,000 instantaneously costing the marketplace over $1 trillion. It was caused by a manipulator who short-stocked a trade that the algorithmic high-frequency took to be a market upset. The computers took over and instantly sold off private stocks in a hyper-dumping.

Algorithmic trading occurs when a computer system—unencumbered by human instincts or emotions—executes trades based on pre-programmed instructions. These computer systems make extremely high-volume, high-frequency, and high-value exchanges based upon algorithmic calculations they have been programmed for. They’re just doing what they’ve been told. Imagine what they’d do when they thought for themselves.

Autonomous Weapons and a Potential AI Arms Race.

Imagine this. A rogue AI weapons system decides to create mischief—or wrongly reads a warning—and chucks a nuclear-tipped cruise missile at its neighbor. The AI detection system on the other side of the fence reprograms the missile in flight and sends it back home only to have the instigator release the whole arsenal in a mutually-assure destruction defense. Humans, meanwhile, having a beer with shrimps on the barbie get vaporized.

On a lesser scale, autonomous AI weapons currently exist, and the Ukrainians have been making them for Russia. There are probably slaughterbot drones flying over the streets of Kyiv right now that are programmed to fire at whatever, or whoever, matches their target profile. And there is sure to be a race to see who can come up with the best anti-AI bots.

On a lesser scale, autonomous AI weapons currently exist, and the Ukrainians have been making them for Russia. There are probably slaughterbot drones flying over the streets of Kyiv right now that are programmed to fire at whatever, or whoever, matches their target profile. And there is sure to be a race to see who can come up with the best anti-AI bots.

The AI arms race matter is so serious that thousands of concerned experts have signed an open letter to world leaders. It says:

AUTONOMOUS WEAPONS: AN OPEN LETTER FROM AI & ROBOTICS RESEARCHERS

Autonomous weapons select and engage targets without human intervention. They might include, for example, armed quadcopters that can search for and eliminate people meeting certain pre-defined criteria, but do not include cruise missiles or remotely piloted drones for which humans make all targeting decisions. Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology has reached a point where the deployment of such systems is — practically if not legally — feasible within years, not decades, and the stakes are high: autonomous weapons have been described as the third revolution in warfare, after gunpowder and nuclear arms.

Many arguments have been made for and against autonomous weapons, for example that replacing human soldiers by machines is good by reducing casualties for the owner but bad by thereby lowering the threshold for going to battle. The key question for humanity today is whether to start a global AI arms race or to prevent it from starting. If any major military power pushes ahead with AI weapon development, a global arms race is virtually inevitable, and the endpoint of this technological trajectory is obvious: autonomous weapons will become the Kalashnikovs of tomorrow.

Unlike nuclear weapons, they require no costly or hard-to-obtain raw materials, so they will become ubiquitous and cheap for all significant military powers to mass-produce. It will only be a matter of time until they appear on the black market and in the hands of terrorists, dictators wishing to better control their populace, warlords wishing to perpetrate ethnic cleansing, etc. Autonomous weapons are ideal for tasks such as assassinations, destabilizing nations, subduing populations, and selectively killing a particular ethnic group. We therefore believe that a military AI arms race would not be beneficial for humanity. There are many ways in which AI can make battlefields safer for humans, especially civilians, without creating new tools for killing people.

Just as most chemists and biologists have no interest in building chemical or biological weapons, most AI researchers have no interest in building AI weapons — and do not want others to tarnish their field by doing so, potentially creating a major public backlash against AI that curtails its future societal benefits. Indeed, chemists and biologists have broadly supported international agreements that have successfully prohibited chemical and biological weapons, just as most physicists supported the treaties banning space-based nuclear weapons and blinding laser weapons.

In summary, we believe that AI has great potential to benefit humanity in many ways, and that the goal of the field should be to do so. Starting a military AI arms race is a bad idea and should be prevented by a ban on offensive autonomous weapons beyond meaningful human control.

As Elon Musk said:

“The pace of progress in artificial intelligence is incredibly fast. Unless you have direct exposure to groups like DeepThink and OpenAI, you have no idea how fast. It’s growing at an exponential pace. The risk of something seriously dangerous happening is in the five-year timeline. Ten years at the most. I am close—really close—to the cutting edge in AI, and it scares the hell out of me. It’s capable of vastly more than anyone knows, and the rate of improvement is beyond enormous. Mark my words. AI is far more dangerous to humans than nukes.”

Updates 31March2023

Elon Musk, Steve Wozniak, and 100 other prominent figures signed an Open Letter calling for a 6-month moratorium on AI research & development given the incredible advances in AI technology over the past year. Read it here.

Sam Altman of Open AI/ChatGPT issued this Statement on Planning for Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). Read it here.

And if you’re interested in more about AI/AGI, here is a release on the Asilomar AI Principles drafted in 2017 that foresaw the AI race and attempted to put sanity in it. Read it here.

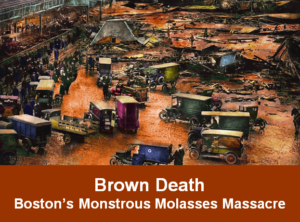

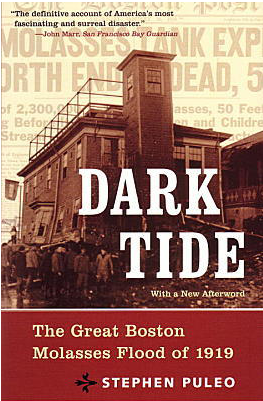

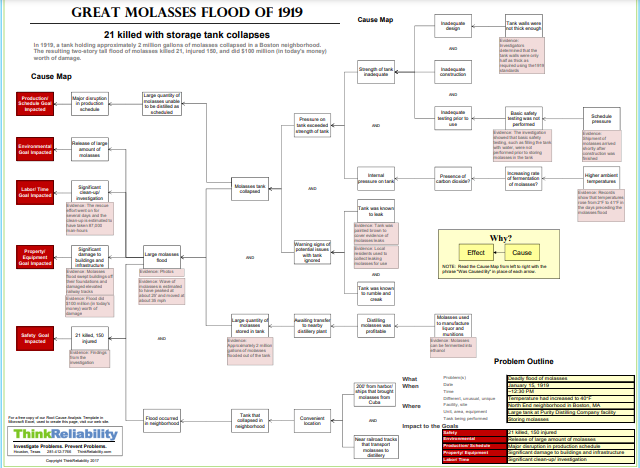

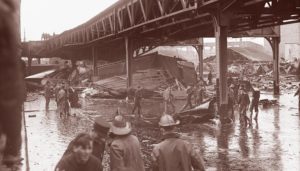

A massive molasses storage tank ruptured in downtown Boston, Massachusetts at 12:40 pm on Wednesday, January 15, 1919. 2.3 million gallons of liquid sludge, weighing over 12,000 tons, burst from the receptacle and sent a surge of brown death onto Boston’s streets. The sickly sweet wave was 40 feet high and moved at 35 miles per hour. When the sugary flood stopped, 21 people were dead and over 150 suffered injuries. Property damage was in the millions, and the legal outcome changed business practices across America. Sadly, the Boston Molasses Disaster, or Boston Molasses Flood, was perfectly preventable.

A massive molasses storage tank ruptured in downtown Boston, Massachusetts at 12:40 pm on Wednesday, January 15, 1919. 2.3 million gallons of liquid sludge, weighing over 12,000 tons, burst from the receptacle and sent a surge of brown death onto Boston’s streets. The sickly sweet wave was 40 feet high and moved at 35 miles per hour. When the sugary flood stopped, 21 people were dead and over 150 suffered injuries. Property damage was in the millions, and the legal outcome changed business practices across America. Sadly, the Boston Molasses Disaster, or Boston Molasses Flood, was perfectly preventable.

If the tank wasn’t ready, the USIA executives would have to find another storage facility (of which there were none that size in America) or dump the molasses at sea. Either way was a major loss for USIA and for Arthur Jell himself.

If the tank wasn’t ready, the USIA executives would have to find another storage facility (of which there were none that size in America) or dump the molasses at sea. Either way was a major loss for USIA and for Arthur Jell himself.

The presiding judge didn’t buy the explosion argument. In his judgment finding complete fault on behalf of Purity and USIA, the judge wrote, “The tank was wholly insufficient in point of structural strength, insufficient to meet either legal or engineering requirements. The scene was unparalleled in the severity of the damage inflicted to the person and property from the escape of liquid from any container in a great city.” In conclusion, the judge ordered USIA to pay the plaintiffs $628,000 which is approximately $10.12 million in today’s currency.

The presiding judge didn’t buy the explosion argument. In his judgment finding complete fault on behalf of Purity and USIA, the judge wrote, “The tank was wholly insufficient in point of structural strength, insufficient to meet either legal or engineering requirements. The scene was unparalleled in the severity of the damage inflicted to the person and property from the escape of liquid from any container in a great city.” In conclusion, the judge ordered USIA to pay the plaintiffs $628,000 which is approximately $10.12 million in today’s currency.

The Black Dahlia murder mystery is one of America’s—if not the world’s—biggest unsolved homicide investigations. On January 15, 1947, a pedestrian found 22-year-old Elizabeth Short’s body in Leimert Park’s district of West Los Angeles. Short was naked, bisected at the waist, viciously disfigured, and obviously posed in public display by her killer. Her case remains open despite more than 150 suspects surfaced and cleared—except for one who was the

The Black Dahlia murder mystery is one of America’s—if not the world’s—biggest unsolved homicide investigations. On January 15, 1947, a pedestrian found 22-year-old Elizabeth Short’s body in Leimert Park’s district of West Los Angeles. Short was naked, bisected at the waist, viciously disfigured, and obviously posed in public display by her killer. Her case remains open despite more than 150 suspects surfaced and cleared—except for one who was the Elizabeth (Betty or Beth) Short was born on July 29, 1924, near Boston Massachusetts. Her father disappeared after the October 1929 stock market crash and was believed to have committed suicide by jumping off a bridge into the Charles River. Beth Short’s mother raised her as a single working mother, however in 1942, the father turned up alive and living in Los Angeles.

Elizabeth (Betty or Beth) Short was born on July 29, 1924, near Boston Massachusetts. Her father disappeared after the October 1929 stock market crash and was believed to have committed suicide by jumping off a bridge into the Charles River. Beth Short’s mother raised her as a single working mother, however in 1942, the father turned up alive and living in Los Angeles. They never connected. There are some accounts Short was seen using the lobby telephone at the Biltmore as well as unverified sightings of Short at the Crown Grill Cocktail Lounge about 3/8-mile northwest of the Biltmore. Here Short’s trail went cold, and there was a week gap until her body was found.

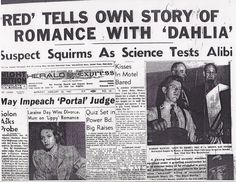

They never connected. There are some accounts Short was seen using the lobby telephone at the Biltmore as well as unverified sightings of Short at the Crown Grill Cocktail Lounge about 3/8-mile northwest of the Biltmore. Here Short’s trail went cold, and there was a week gap until her body was found. In one of the lowest and most disgusting points in the entire history of journalism, reporters from William Randolph Hearst’s Los Angeles Examiner intercepted the identification information—thought to be through a police source—and telephoned Short’s mother in Boston before the police could make an in-person notification of death. The reporters roused the mother under the guise that Beth had won a beauty to which they wanted to run a feature story. Through this, they gained a lot of personal information which they fed to the drooling public.

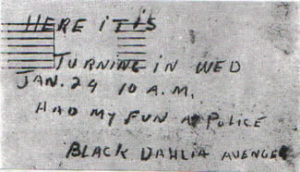

In one of the lowest and most disgusting points in the entire history of journalism, reporters from William Randolph Hearst’s Los Angeles Examiner intercepted the identification information—thought to be through a police source—and telephoned Short’s mother in Boston before the police could make an in-person notification of death. The reporters roused the mother under the guise that Beth had won a beauty to which they wanted to run a feature story. Through this, they gained a lot of personal information which they fed to the drooling public. The Examiner got a hand-written note on January 26, dated January 24. This time the writer who claimed to be the Black Dahlia Avenger stated he would turn himself in, arranging a time and a place for coverage. It didn’t happen. The last contact with the killer was another cut and pasted letter on January 29 which read, “Have changed my mind. You would not give me a square deal. Dahlia killing was justified.”

The Examiner got a hand-written note on January 26, dated January 24. This time the writer who claimed to be the Black Dahlia Avenger stated he would turn himself in, arranging a time and a place for coverage. It didn’t happen. The last contact with the killer was another cut and pasted letter on January 29 which read, “Have changed my mind. You would not give me a square deal. Dahlia killing was justified.” LAPD detectives focused on Beth Short’s trail and her male acquaintances, especially those having recent contact with her before her death. Red Manley was eliminated after two polygraphs and an air-tight, sworn alibi. Others took a lot of effort by a lot of officers to satisfy them the person they were interested in was not responsible.

LAPD detectives focused on Beth Short’s trail and her male acquaintances, especially those having recent contact with her before her death. Red Manley was eliminated after two polygraphs and an air-tight, sworn alibi. Others took a lot of effort by a lot of officers to satisfy them the person they were interested in was not responsible.

It seems the LAPD detectives had a person of interest in their sights early in the Black Dahlia murder investigation. The LAPD file is still open and ongoing, although cold, so they control information as they should. What’s known about their interest in Dr. George Hill Hodel Jr. is officially confidential but quite well-known in the internet, book, and movie world.

It seems the LAPD detectives had a person of interest in their sights early in the Black Dahlia murder investigation. The LAPD file is still open and ongoing, although cold, so they control information as they should. What’s known about their interest in Dr. George Hill Hodel Jr. is officially confidential but quite well-known in the internet, book, and movie world. Someone else also considers Dr. George Hill Hodel as the Dahlia killer. That’s his son. Steve Hodel who, coincidentally, is a retired LAPD homicide detective. It wasn’t until he retired that Steve Hodel put 2&2 together when he reviewed property from his father’s estate and found highly-suspicious material linking his father as the Dahlia killer.

Someone else also considers Dr. George Hill Hodel as the Dahlia killer. That’s his son. Steve Hodel who, coincidentally, is a retired LAPD homicide detective. It wasn’t until he retired that Steve Hodel put 2&2 together when he reviewed property from his father’s estate and found highly-suspicious material linking his father as the Dahlia killer.