“Sounded like someone was skinning a live cat,” the neighbor told us. She sniffed, wiping her eyes. “Then loud crashing and banging, then… everything went quiet. I waited a while, didn’t hear nothing more, so I went and checked and found him dead on the floor.”

“Sounded like someone was skinning a live cat,” the neighbor told us. She sniffed, wiping her eyes. “Then loud crashing and banging, then… everything went quiet. I waited a while, didn’t hear nothing more, so I went and checked and found him dead on the floor.”

I was in my first year of coroner understudy and shadowing my mentor, senior coroner Barbara McCormick. We were in the kitchen of a tiny suite on the poor side of town, standing over this skinny, old guy who was in a semi-fetal position with one arm wrapped around his abdomen and his other hand clutching his throat. I’ll never forget his wide-open eyes or the gritting grimace of teeth—the expression of excruciating pain etched in a cold, deathly stare.

“Heart attack or brain aneurysm, Barb?” I asked, ready to flip a coin. I was new to the coroner service, but no stranger to dead bodies after a career as a homicide cop. There was zero sign of foul play at this scene and my experience told me people only drop dead from one of these two natural events.

Barb was bent over, starting the head-to-toe examination that coroners do before removing a body for a thorough autopsy back at the morgue. “Wouldn’t bet on either.” Barb was trying to pry his jaw for a look down the throat. “Check his color. Blue-gray. He’s asphyxiated. I’m thinking he might have choked on something but, for the life of me, I don’t know how he could let out a curdling cat-scream if something was stuck in his yap.”

Barb was bent over, starting the head-to-toe examination that coroners do before removing a body for a thorough autopsy back at the morgue. “Wouldn’t bet on either.” Barb was trying to pry his jaw for a look down the throat. “Check his color. Blue-gray. He’s asphyxiated. I’m thinking he might have choked on something but, for the life of me, I don’t know how he could let out a curdling cat-scream if something was stuck in his yap.”

While Barb was messing with his head, I snooped around. It was typical digs for a single pensioner—a bachelor suite crammed with junk. Empty booze bottles and overflowing ashtrays testified to a lifestyle that suggested he should be dead of something by now. I checked for meds, which was routine. The pathologist would want to know what was likely in his system and the toxicology lab would want it for sure.

I found the usual pill vials indicating treatment for coronary and respiratory ailments that heavy drinkers and smokers all have. The place was relatively clean, although cluttered, and didn’t reek of garbage and bodily waste like most of these places do. I saw a part-eaten sandwich on the table and a freshly cracked beer—seemed like the old boy was doing lunch when violently seized by the death monster and taken down hard to the mat.

I found the usual pill vials indicating treatment for coronary and respiratory ailments that heavy drinkers and smokers all have. The place was relatively clean, although cluttered, and didn’t reek of garbage and bodily waste like most of these places do. I saw a part-eaten sandwich on the table and a freshly cracked beer—seemed like the old boy was doing lunch when violently seized by the death monster and taken down hard to the mat.

Barb stood up, looking puzzled. “I have no idea. Should be an interesting postmortem.” We finished photographs, bagged the man, then stretchered him out to the transport van and drove him off to the morgue.

We’d recorded his personal details, which is part of a death investigation, but his real name never stayed with me. Most are like that. In the death business it’s not a good idea to get too close to your clients, but some you never forget because of how they checked out.

It’s normal—in black humor behind the scenes—for coroners to name their files by earned handles. I’ll always remember Capn’ Crab Bait, Voltage Vern, Methlab Mikey, Arachnoid Ann, Lawn Tractor Guy, Tarzan of the Caterpillars, Freight Train Ference, The Krosswalk Kidd, The Drill Sergeant, Pole Dancer, Cats-Sup, and… as long as I live… I’ll never forget The Electric Carving Knife Lady.

It’s normal—in black humor behind the scenes—for coroners to name their files by earned handles. I’ll always remember Capn’ Crab Bait, Voltage Vern, Methlab Mikey, Arachnoid Ann, Lawn Tractor Guy, Tarzan of the Caterpillars, Freight Train Ference, The Krosswalk Kidd, The Drill Sergeant, Pole Dancer, Cats-Sup, and… as long as I live… I’ll never forget The Electric Carving Knife Lady.

And, it came to pass, I’ll also never forget the dead little man we’d just rolled into the cooler.

Next morning my favorite pathologist, Dr. Elvira Esikanian, was on the roster to autopsy our guy from the kitchen floor. I loved dealing with Elvira. She’s Bosnian with a wicked sense of dry humor and an equally wicked curriculum vitae, including exhuming mass graves for the UN and serving in some of the busiest morgues around the world where she’d often do a dozen different cuttings per day.

Although Elvira was exceptionally thorough, she was a go-to-the-throat prosector. She’d assess the circumstances, then head straight to the most likely cause.

Although Elvira was exceptionally thorough, she was a go-to-the-throat prosector. She’d assess the circumstances, then head straight to the most likely cause.

“I’m suspecting an acute respiratory event,” Elvira stated. “Note the petechiae in the eyes.” She pointed to pricks of blood in his whites. “We normally see petechiae in cases of sudden and severe loss of oxygen, such as in strangulation, although on this man I see no sign of exterior trauma.”

We Y-incisioned the thorax/abdominal cavities and began removing organs.

“His lungs are clear, with the exception of tobacco effects.” Elvira had cross-sectioned them. “And his airway is unobstructed. This man did not choke, nor was he suffocated by fluid.” She examined the heart, which showed expected signs of advanced coronary artery disease. “And he did not suffer a heart attack.” Elvira placed the gastro-intestinal tract in a plastic tub and set it aside on her bench.

“His lungs are clear, with the exception of tobacco effects.” Elvira had cross-sectioned them. “And his airway is unobstructed. This man did not choke, nor was he suffocated by fluid.” She examined the heart, which showed expected signs of advanced coronary artery disease. “And he did not suffer a heart attack.” Elvira placed the gastro-intestinal tract in a plastic tub and set it aside on her bench.

She proceeded straight to a cranial exam, inspecting for the tell-tale bleed of a cerebral hemorrhage. “Nothing obvious here.” Elvira put the brain in a stainless bowl. “You indicated this man was eating lunch when he expired.” She looked at me. I nodded. She reached for her plastic tub. “I’m going to examine the stomach.”

For most pathologists and coroners, digging in the digestive tract is the most unpleasant part of the job. It was no different with this man. Elvira incised the stomach and poured its contents into a clear, glass tray. She flipped on her magnifiers and bent a gooseneck light overtop. Immediately, she let out a wolf-whistle. “Look at this!”

For most pathologists and coroners, digging in the digestive tract is the most unpleasant part of the job. It was no different with this man. Elvira incised the stomach and poured its contents into a clear, glass tray. She flipped on her magnifiers and bent a gooseneck light overtop. Immediately, she let out a wolf-whistle. “Look at this!”

To me, it was a messy slime-goo of chewed bread mixed with some rude and red, pasty substance.

To Elvira, it was the smoking gun.

I watched Elvira excise a culture, fix it in a slide, and examine it under her microscope. “Have a look.” She directed me to the eyepieces.

I watched Elvira excise a culture, fix it in a slide, and examine it under her microscope. “Have a look.” She directed me to the eyepieces.

What I saw was a squiggling biological mass of sub-terrain aliens—looking out-of-this-world like agitated, animated, turquoise tampons breathlessly mingling in a magnified mess of greenish-gray snot.

I swear they had heads, horns, and hoofs.

“Clostridium Botulinum,” Elvira announced. “Botulism. I’m sure this man died from the deadliest food poison known.”

Now, I’d heard of botulism. Everyone has. That’s why my mum would sniff the tin cans when she opened them and why she’d boiled preserves for four hours. But this was the first time I’d seen a real case of botulism.

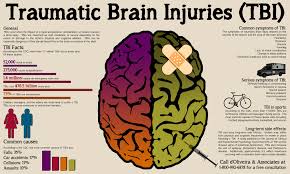

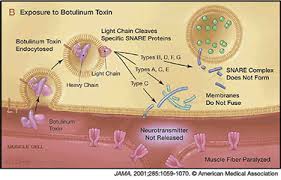

“We won’t know the strain or the severity level until we get toxicology results but I can tell you, given how quickly this poor fellow expired, it must be an extremely toxic ratio.” Elvira went on. “What happens is the neurotoxin produced by the botulinum bacteria acts as a blocking agent preventing neurotransmitters from issuing instructions to the muscles. Once this poison hit his system, every nerve in his body would have felt on fire and he’d quickly fall into total paralysis. That would soon stop his lungs and he’d fall into a state of anoxia, or lack of oxygenated blood to the brain. He’d be conscious throughout and would feel everything… but would be unable to react.”

“We won’t know the strain or the severity level until we get toxicology results but I can tell you, given how quickly this poor fellow expired, it must be an extremely toxic ratio.” Elvira went on. “What happens is the neurotoxin produced by the botulinum bacteria acts as a blocking agent preventing neurotransmitters from issuing instructions to the muscles. Once this poison hit his system, every nerve in his body would have felt on fire and he’d quickly fall into total paralysis. That would soon stop his lungs and he’d fall into a state of anoxia, or lack of oxygenated blood to the brain. He’d be conscious throughout and would feel everything… but would be unable to react.”

She glanced at the cut-open cadaver on her examining table. “What a positively excruciating way to die.”

Barb McCormick already had her digital camera out and was scrolling through shots from the scene. “This might be it.” Barb enlarged a photo showing the kitchen. Evident was a jar with its top off, containing a reddish substance.

Barb McCormick already had her digital camera out and was scrolling through shots from the scene. “This might be it.” Barb enlarged a photo showing the kitchen. Evident was a jar with its top off, containing a reddish substance.

Realizing the lethality of the situation and the danger to others, Barb and I immediately went back to the apartment. There, on the counter, was a jar of red pepper paste with a label indicating it originated in China and was far past its expiry date. A tag showed it’d been purchased at the Dollar Store.

Cautiously, we peered inside.

And—I’m here to tell you—that red, peppery, pasty scum was actually moving.

It took over a month for the toxicology results to come back. They proved positive for Botulinum toxin—Type E—and the dosage was staggering.

It took over a month for the toxicology results to come back. They proved positive for Botulinum toxin—Type E—and the dosage was staggering.

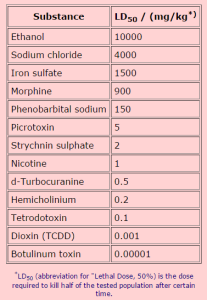

Toxicology measures the presumed lethal dose of a substance in digital units of LD50/ (mg/kg) which translates to the Lethal Dose (LD) required to kill half of the tested laboratory animals in a controlled volume and time.

The LD for Botulinum toxin is 0.00001. Our red pepper paste man’s reading was over 0.02000—two thousand times the amount needed to kill a human being.

* * *

It’s been a few years since the red pepper paste case and I thought I’d review the pathology around Botulinum toxin. Here’s a quote from a paper by the World Health Organization on the medical process of how botulism works on the human body:

It’s been a few years since the red pepper paste case and I thought I’d review the pathology around Botulinum toxin. Here’s a quote from a paper by the World Health Organization on the medical process of how botulism works on the human body:

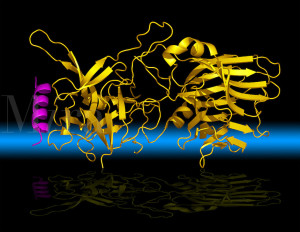

To understand the role of Botulinum toxin, it is necessary first to understand how the brain initiates a muscle contraction as it is in this process that Botulinum toxin intervenes.

Muscles are connected to the brain by the nervous system which is a complex network of neurons – these are long cells that can pass information using either electrical or chemical signals. Chemical signals pass between neurons and muscles through synapses, which are specialized connections linking cells. The chemicals that are used to pass these messages are called neurotransmitters.

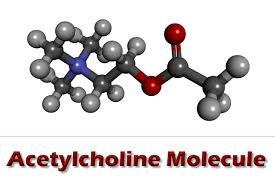

In the case of a muscle contraction, the chemical signal is passed using a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine. This sits in the neuron in a vesicle, a small bubble surrounded by a membrane, until it is required. When the neuron receives a message from the nervous system to initiate a muscle contraction, the acetylcholine is released from the vesicle and passes through the synapse into the muscle fiber.

In the case of a muscle contraction, the chemical signal is passed using a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine. This sits in the neuron in a vesicle, a small bubble surrounded by a membrane, until it is required. When the neuron receives a message from the nervous system to initiate a muscle contraction, the acetylcholine is released from the vesicle and passes through the synapse into the muscle fiber.

To achieve this, the vesicles need to be transported to, and fuse with, the neuron membrane that adjoins the synapse between the nerve and the muscle. This process is controlled by a group of proteins called the SNARE complex.

The three main proteins involved are Syntaxin (which connects to the nerve membrane), Synaptobrevin (which connects to the vesicle) and SNAP-25 (which helps the other SNARE proteins link up). These proteins join together to cause the vesicle to move to the nerve membrane and fuse with it. The acetylcholine can then be released across the synapse and pass into the muscle. This then triggers a chain of events that causes the muscle contraction.

The three main proteins involved are Syntaxin (which connects to the nerve membrane), Synaptobrevin (which connects to the vesicle) and SNAP-25 (which helps the other SNARE proteins link up). These proteins join together to cause the vesicle to move to the nerve membrane and fuse with it. The acetylcholine can then be released across the synapse and pass into the muscle. This then triggers a chain of events that causes the muscle contraction.

Botulinum toxin prevents the release of acetylcholine through the synapse.

Botulinum toxin is produced by a bacterium called Clostridium Botulinum. This bacterium is associated with causing botulism, a rare but deadly form of food poisoning.

Botulinum toxin is exceptionally toxic but, when purified and used in tiny, medically controlled doses, it can be used effectively to relax excessive muscle contraction and is now commonly used in cosmetic surgery.

Botulinum toxin is exceptionally toxic but, when purified and used in tiny, medically controlled doses, it can be used effectively to relax excessive muscle contraction and is now commonly used in cosmetic surgery.

Hmmm… BOtulinum TOXin… BoTox.

The same gruesome stuff in the red pepper paste that painfully killed our old man is commonly stuck into people’s faces to make them look younger and pretty.

The same gruesome stuff in the red pepper paste that painfully killed our old man is commonly stuck into people’s faces to make them look younger and pretty.

I’m sure, for the most part, BoTox injections are perfectly safe. But… if you’re thinking of cosmetically shedding some years, remember the Excruciating Death of Mister Red Pepper Paste Man.