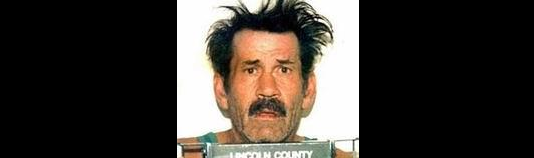

Colin Pitchfork. Just the name conjures up a devilish image—an evil monster—a story-villain of homicidal psychopathy. But Colin Pitchfork wasn’t a fictional work, though, like Hannibal Lecter. Pitchfork was a real serial murderer and sexual deviant who raped and strangled at least two teen girls in England in the mid-1980s as well as committing countless sexual offenses. And he was the first killer in the world to be convicted through DNA forensic evidence.

Colin Pitchfork. Just the name conjures up a devilish image—an evil monster—a story-villain of homicidal psychopathy. But Colin Pitchfork wasn’t a fictional work, though, like Hannibal Lecter. Pitchfork was a real serial murderer and sexual deviant who raped and strangled at least two teen girls in England in the mid-1980s as well as committing countless sexual offenses. And he was the first killer in the world to be convicted through DNA forensic evidence.

Four decades later, DNA forensic evidence is commonplace. So commonplace, in fact, that juries expect it. Through a phenomenon called the CSI Effect, clever defense counsels can plant doubtful seeds in jurors’ minds where they’ll wrongfully acquit a perfectly guilty person if there’s no DNA evidence linking the accused to the crime.

That wasn’t the case with Colin Pitchfork. He was perfectly guilty of murder, and DNA evidence proved it. We’ll look at the Pitchfork case facts in a moment and then do a DNA Forensic Evidence 101 crash course, but first let me tell you a bit of my police investigation background and why I have the authority to write this piece on the birth of DNA forensic evidence.

In the 1990s, when DNA evidence was under development, I was an active homicide detective with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) Serious Crimes Section. I was peripherally involved in surreptitiously collecting a biological sample from a suspect (later convicted) in the first DNA evidence trial in Canadian courts. Ryan Jason Love was taken down solely through DNA evidence for the 1990 murder of Lucie Turmel, a female cab driver who Love stabbed to death in the resort town of Banff, Alberta.

In the 1990s, when DNA evidence was under development, I was an active homicide detective with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) Serious Crimes Section. I was peripherally involved in surreptitiously collecting a biological sample from a suspect (later convicted) in the first DNA evidence trial in Canadian courts. Ryan Jason Love was taken down solely through DNA evidence for the 1990 murder of Lucie Turmel, a female cab driver who Love stabbed to death in the resort town of Banff, Alberta.

I was in the right place at the right time (DNA career-wise) in 1995 when Canada passed Bill C-104 Forensic DNA Analysis, a federal law. This legislation authorized search warrants for DNA sample collection on uncooperative suspects. The day the bill passed senate assent, I investigated a violent sexual assault where a police dog tracked and not-so-gently tackled a fleeing suspect. I executed the first DNA search warrant in Canada that resulted in convicting serial rapist Rodney John Camp.

Enough about me and my DNA exploits. Let’s take a quick look at the Colin Pitchfork murders and then try to make simple sense of this complicated business called DNA forensic evidence.

The Colin Pitchfork Murders

In November 1983, 15-year-old Lynda Mann’s body was found in the Narborough area of England, approximately one hundred miles northwest of London. She’d been beaten, raped, and murdered along a deserted pathway known as the Black Pad. Forensic evidence, at that time, determined semen on her was from a relatively common blood type that matched ten percent of males. The case fell cold after months of extensive investigation.

A second girl, 15-year-old Dawn Ashworth was found dead in July 1986. She’d also been beaten, raped, and strangled in a secluded Narborough footpath called Ten Pound Lane. As with Lynda Mann, the same semen type was on and in her body.

A second girl, 15-year-old Dawn Ashworth was found dead in July 1986. She’d also been beaten, raped, and strangled in a secluded Narborough footpath called Ten Pound Lane. As with Lynda Mann, the same semen type was on and in her body.

The Ashworth investigation revitalized the Mann file and the two cases became the Narborough Enquiry. Famed American crime writer Joseph Wambaugh would later write his book The Blooding about the phenomenal effort British authorities put into the investigations. Homicide detectives knew they had a serial killer—the similar blood types, the locations, and the modus operandis (MOs) were too strikingly similar to suggest otherwise.

The question was who donated the semen and how police could conclusively prove it.

Enter Alec Jefferys and his scientific team at the British Forensic Science Service. They’d been hard at work identifying Deoxyribonucleic Acid—the DNA double-helix molecule that provides a genetic fingerprint that’s unique to an individual except for identical twins. Jefferys & Company knew they were onto a world-changing forensic evidence breakthrough, and they used the Narborough Enquiry as a test case.

Initially in the Ashworth file, a strong suspect developed. He was a developmentally challenged youth named Richard Buckland who confessed under duress to the Dawn Ashworth murder. However, Buckland strongly denied the Lynda Mann slaying.

By late 1986, Alec Jefferys’ team had their DNA identification process to the point where they were confident it could withstand courtroom scrutiny. The police took a blood sample from Richard Buckland and delivered it to the Jefferys lab. Conclusively, the lab results said, Buckland was not the semen donor in either the Mann or Ashworth killings. However, the DNA profile conclusively proved the Narborough killer was the same man.

Richard Buckland was a first—the first wrongfully accused person to be exonerated by DNA forensic evidence. Relying on a false confession is a law enforcement lesson harshly learned by detectives, but the British investigators moved on to find the real killer. The question was how?

The answer was a process of elimination.

The Narborough Enquirers took on the monumental task of getting blood samples for DNA analysis from as many late teen and adult males in the Narborough region as possible. This became known as “blooding” suspects and, after over 4,500 bloodings, it paid off.

In August 1987, police got a tip that one Ian Kelly had fraudulently submitted his blood sample to cover up for a friend, Colin Pitchfork. Both men worked as bakers in Narborough, and the plan backfired. Police took blood from Pitchfork under a court order. It matched the semen DNA profile in the Mann and Ashworth murders.

Colin Pitchfork confessed and got a life sentence. He also admitted to performing around 1,000 indecent exposure acts as well as other violent sexual assaults. Pitchfork’s motive for killing Lynda and Dawn, he said, was not for sexual gratification. He did it because the girls could identify him.

Since the first blooding that led to DNA forensic being soundly based in worldwide courtrooms, and even compounding the frustrating CSI Effect problem, DNA extraction and processing science has advanced leaps and bounds. Today, processing DNA for forensic evidence is mostly routine. Here’s a brief look—call it a crash course—in DNA Forensic Evidence 101.

DNA Forensic Evidence 101

Scientists have studied genetics since the early 1800s when Gregor Mendel suggested his theory that all living organisms had genetic blueprints that described and allowed their physical structure. Mendel also theorized all living organisms shared basic hereditary traits. Mr. Mendel did an interesting experiment with peas and proved that dominant and recessive genes got passed from parent to offspring. It’s a principle applying to peas and humans alike.

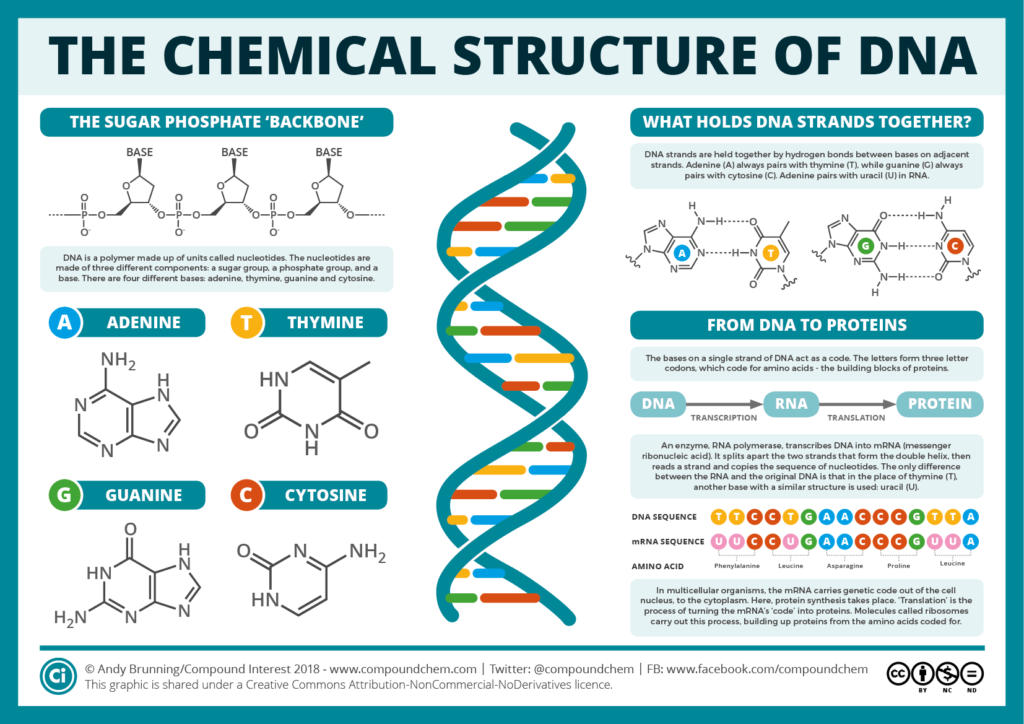

In the 1860s, Friedrich Meischer was the first to identify DNA in human blood white cells. (Note: DNA molecules do not appear in red blood cells because red cells are not really cells—they don’t have a nucleus which DNA needs to build a cell—DNA being the building blocks of cells.) By the 1920s, mainstream science widely accepted the DNA theory of genetics and inherited traits. And in the 1950s, famed genetic scientists James Watson and Francis Crick accurately described and isolated chemical structure in the double helix molecule.

Knowledge of this structure, the double helix, allowed Alec Jeffreys and his team to develop extraction, multiplication, and comparison techniques of DNA signatures within all species. DNA blueprints are present in the smallest of life’s creatures like gastropod mollusks to the largest like blue whales and are around 99.9% similar in every living species known to science. It’s that small 0.1% difference that makes species, and specimens within each species, entirely unique.

Your human body produces around 230 billion new cells each day. Nature programmed you for cell division where, uncontrolled by your conscious actions, your cells will divide into two with the new half receiving behavioral instructions from the old half. People being people and nature being nature, there are always small errors or slight changes to the genetic blueprint. Over time and through trillions of cell splits, we all become slightly different. Except, of course, for monozygotic or identical twins. (Science now finds tiny differences in monozygotic DNA structures at the mitochondrial level, but that’s for DNA 301.)

Genetic mistakes, or unintended differences, are where forensic scientists capitalize for evidence. Variances in DNA replication or sequences are called Single Nucleotide Polymorphism or SNPs. These variances normally go unnoticed, health-wise, but they’re the reasons things like hair and eye color vary, metabolisms aren’t the same in family members, and possibly why some seem to have God-given talents.

There really isn’t a lot known about why some relatives have two left feet and why some are Olympic athletes, but one thing that can be taken to the evidentiary bank is each human (save for those pesky twins) have tiny DNA blueprint variances, and that’s where the forensic folks go when examining DNA evidence.

Without stepping into DNA Forensic Evidence 201 or beyond, what’s needed for this crash course is knowing about markers and loci. DNA scientists break down the individual biological sample they’re examining and give it a barcode snapshot similar to a binary code. They have highlights called markers and loci which show unique traits of the sample. Quite simply, they make a graph of the markers and loci then compare the sample they’re questioning against the “known” one. If the markers and loci match, it’s an identification.

Caution! Spoiler Alert: DNA forensic evidence matching isn’t an exact science. It’s a complicated and precise process but, unlike fingerprinting with ridges, valleys, whorls, deltas, and accents which are 100% physically conclusive—to the elimination of all other humans in the world—DNA matches rely on conclusions based on statistical probabilities. However, the statistical matching models return such enormously large matching probabilities of 1:13 billion and such, that this circumstantial opinion or viewpoint is regularly accepted by juries as cold, hard fact.

DNA Forensic Evidence 101 isn’t the place to examine specific processing techniques like Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP), Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), Short Tandem Repeats (STR), or Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism (ALFP). It’s not the place to touch on Touch DNA (Low Level DNA), Mixtures, Rapid DNA, CODIS, or Southern Blot analysis. But it’s worthwhile knowing the DNA evidentiary processing chain from crime scene to courtroom. It goes like this:

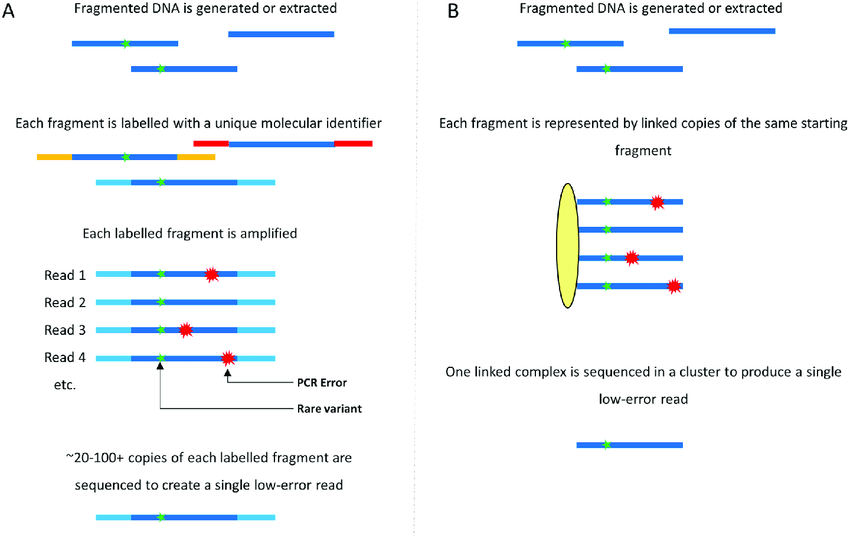

Collection — where a biological sample is found at a crime scene.

Extraction — where DNA is released from the cell at the lab.

Quantification — where the lab determines how much DNA they have to work with.

Amplification — where the lab copies the DNA to characterize it.

Separation — where the lab separates amplified DNA for identification.

Analysis and Interpretation — where the lab compares DNA to other known profiles.

Statistical Computation — where the lab calculates a match’s probability.

Quality Assurance — where the lab triple checks process accuracy.

Evidence Delivery — where the lab testifies about their conclusion(s).

In 1987, the birth of Colin Pitchfork’s DNA evidence process was slow, labor extensive, and extremely expensive. It might have even been painful. That’s no longer the case, as four decades has taken this science—originally deemed pseudoscience—and molded it into fast, economical, and highly reliable forensic evidence used around the world. Now, if science could find a permanent remedy for the CSI Effect, that’d be a real breakthrough.

So, you’ve graduated from the DyingWords crash course in DNA Forensic Evidence 101 and your certificate is in the mail. If there’s enough interest, I may run crash courses 201 and 301 where I’ll invite some expert DNA guest lecturers to explain the differences between loci and markers and why the Southern Blot is so slow compared to Rapid and maybe talk fun stuff like Touch DNA, Mixtures, CODIS, and Dirty. In the meantime, if you’d like to continue with this third-degree program, here are five Forensic DNA websites well worth checking out:

http://www.forensicsciencesimplified.org/dna/DNA.pdf

https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/bc000657.pdf

https://wyndhamforensic.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/WyndhamForensic_Presentation_DNAAnalysis.pdf

https://www.fbi.gov/services/laboratory