“Whatever the mind can conceive and believe, it can achieve with a planned definite purpose and a positive mental attitude.” This statement is true. I attest to this, and you can take it to the bank. It’s the core of Napoleon Hill’s Science of Personal Achievement set out in seventeen principles nailed within his timeless book Think And Grow Rich. The only specters stopping you from achieving your biggest dreams and your deepest desires are the six ghosts of fear.

“Whatever the mind can conceive and believe, it can achieve with a planned definite purpose and a positive mental attitude.” This statement is true. I attest to this, and you can take it to the bank. It’s the core of Napoleon Hill’s Science of Personal Achievement set out in seventeen principles nailed within his timeless book Think And Grow Rich. The only specters stopping you from achieving your biggest dreams and your deepest desires are the six ghosts of fear.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt famously said, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” As wise as President Roosevelt was, he failed to qualify his statement. FDR never said six ghosts are manifesting in different ways to create fear in your mind. Napoleon Hill did. Napoleon Hill also said these six ghosts are caused by indecision and doubt, blending in your subconscious to become fear.

Ghosts exist only in your mind. They’re not real entities. They have no physical presence. But, if you give ghosts merit and lodge them in your mind, then they might as well be real. The same goes with the top six things people—like you—mentally fear.

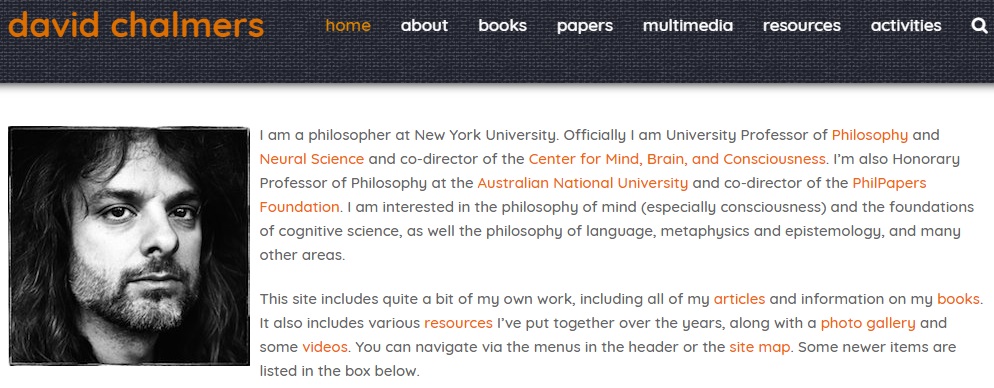

Before I list the six ghosts of fear and drill down as to why they psychologically exist to haunt your personal achievement, let me tell you a story about how I got hooked on Napoleon Hill’s success philosophy, busted the six ghosts, and what led to today’s Dyingwords post.

“Amway.”

“Am…way?”

“Yeah. Amway.”

I hear your gasp and I feel your shudder. I taste your bile and I can see your wide-open eyes. I can even smell gas passing from the shock that anything good comes from Amway.

“Amway is a cult!” you say. “Garry Rodgers can’t possibly be in a cult! A multi-level marketing scam! A pyramid scheme! The terror! The horrifying fear! Say it’s not so!”

Okay. Relax. Breathe easy. Thirty years ago some friends got involved in Amway. With interest, Rita (my wife) and I watched them change from mediocre, basic-get-by folks to this highly-energized and enthusiastic pair of newly-made entrepreneurs. It wasn’t long before they “showed us the plan”.

I was skeptical, like most cops are skeptics of anything perceived to be sneaky. Problem was… my friend showing Rita and I the plan was also a cop—a cop I respected and I knew was no kook. They must be onto something, I thought.

Rita and I initially signed up as customers—not as distributors, or business owners as Amway terms its distribution line people—certainly not before we thoroughly checked this thing out. We went to a few town hall Amway meetings and one large convention in Portland. I had never seen a group of people so pumped about selling soap. It was enlightening.

“How does this happen?” I asked my Amway-distributing police pal. “How do so many people get so supercharged by this soap-selling business?”

“Mindset,” he said. “It’s all about mindset and belief. That and they’ve made a decision to build their Amway business, have no doubt that it works, and they’ve exorcised the six ghosts of fear that prevent people from achieving their dreams.”

“The six ghosts of fear?”

“Yeah. The six ghosts of fear.” That’s when my law enforcement colleague and Amway recruiter handed me a copy of Think And Grow Rich. “Read this,” he said. “Then we’ll talk.”

I read Think And Grow Rich. I’ve read its sequel, The Master Key To Riches, and I’ve read pretty much everything ever published by Napoleon Hill and the Napoleon Hill Foundation. I’ve watched Napoleon Hill’s grainy old videos, and I’ve listened to original cassette recordings of the old man professing his seventeen principles that form the basis of all success—regardless where you find “success” or how you define it.

I read Think And Grow Rich. I’ve read its sequel, The Master Key To Riches, and I’ve read pretty much everything ever published by Napoleon Hill and the Napoleon Hill Foundation. I’ve watched Napoleon Hill’s grainy old videos, and I’ve listened to original cassette recordings of the old man professing his seventeen principles that form the basis of all success—regardless where you find “success” or how you define it.

Soon, Rita and I signed as distributors, but we never did anything with our Amway business, although I still believe there is enormous potential for the few who do Amway right. Life got in the way to spend the time required to build a distributor chain—life being a very busy detective job and the priority of raising two little kids on a cop’s salary with a stay-at-home mom. Our friends did climb the Amway ladder and, from them, we continued to buy the best soap and consumable products available on this planet.

Slowly, we parted ways with Amway’s outer world. I was never comfortable with Amway as an organization. The products were great, but the Amway delivery system sucked and their recruitment model was less than open. Deep down, I had a fear of this thing—especially the fear of criticism or what “they” would think or say. My fear of criticism was greater than my fear of poverty which is what Amway’s business model promised to fix—building astounding wealth… if you worked their plan properly.

But what Amway did was change my inner world. I got hooked on Napoleon Hill’s science of personal achievement philosophy. Without any shred of a doubt, my mindset changed when exposed to Think And Grow Rich. It’s responsible for what I’ve become and for what I’m up to today.

That’s creating the new netstream video, audio, print, and ebook series of hardboiled detective fiction titled City Of Danger. I’m treating this project as a new business venture outside of my regular writing and publishing work. Right now, I’m finishing a business plan for the City Of Danger series based on Napoleon Hill’s seventeen principles that have proven so successful—time and time and time again.

Part of my business plan formulation was reading a recently released book titled Think and Grow Through Art and Music. It’s released by the Napoleon Hill Foundation and aimed at motivating artists like writers and musicians. I’ve read it with my red pen and yellow highlighter. When I came to the final chapter titled The Six Ghosts Of Fear, I realized that, long ago, I’d destroyed those demons. Being ghost-free gives me the courage and confidence to tackle a massive project like City Of Danger.

Part of my business plan formulation was reading a recently released book titled Think and Grow Through Art and Music. It’s released by the Napoleon Hill Foundation and aimed at motivating artists like writers and musicians. I’ve read it with my red pen and yellow highlighter. When I came to the final chapter titled The Six Ghosts Of Fear, I realized that, long ago, I’d destroyed those demons. Being ghost-free gives me the courage and confidence to tackle a massive project like City Of Danger.

So what are the six ghosts of fear? Let’s let Napoleon Hill introduce you.

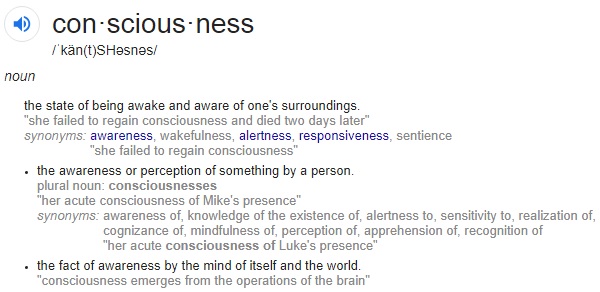

“Before you can put any portion of my seventeen principles into successful use, your mind must be prepared to receive it. The preparation is not difficult. It begins with study, analysis, and understanding of three enemies you have to clear out. These are indecision, doubt, and fear. Members of this unholy trio are closely related; where one is found, the other two are close at hand.

Indecision is the seedling of fear. Indecision crystallizes into doubt, the two blend and become fear. The blending process often is slow and makes the three enemies so dangerous because they germinate and grow without their presence being observed.

There are six main categories of fear. All six reside in the mind, and none have any more reality than a ghost. These six ghosts of fear, on their own or in some combination with each other, are non-realities every person suffers with at some time. Most people are fortunate if they do not suffer from the entire six.”

———

Fears are nothing more than states of mind. One’s mind state is subject to control and direction combined with one’s mental attitude and definite purpose. Here are the six ghosts of fear in order of their most common appearance.

The Fear of Poverty

Poverty bites. I relate to a quote from Vancouver billionaire Jimmy Pattison who said, “I’ve been rich. I’ve been poor. Rich is better.”

I think there are two people types. There are those with success consciousness and those with poverty consciousness. This consciousness resides in the mind and is influenced by three things:

I think there are two people types. There are those with success consciousness and those with poverty consciousness. This consciousness resides in the mind and is influenced by three things:

- Who you associate with

- Your mind input

- The decisions you make

Poverty is the most destructive ghost and the most difficult fear to master. It’s amplified by indifference, indecision, doubt, worry, over-caution, procrastination, and plain laziness. Poverty is overcome by living within means, applying a definite purpose, having confidence, doing the hard work, associating with the right people, adopting a positive mental attitude, and making sensible decisions.

Poverty is the opposite of riches. It’s more than having money or having no money. Poverty and riches extend beyond financial means. They include your physical health, your mental state, and your spiritual well-being.

The Fear of Criticism

What “they” say or think. I was fearful of what they would think and say about my, and Rita’s, brush with Amway. This was all in my head. I never had one person say to me or anyone else (that I know of) that I was getting sucked into a cult.

Who are “they”? They are entirely imaginary beings—just like ghosts—but they’re surprisingly powerful. They stupefy enthusiasm. They cut down personal initiative. They destroy your imagination. And they make it practically impossible to achieve anything beyond mediocrity.

While poverty is the most entrapping ghost, the fear of criticism is the most common ghost that holds you back—the fear of how other people might judge your work, your creativity, and your ideas of how to wildly succeed as an entrepreneurial business person.

The criticism ghost browbeats you. It inseminates a lack of poise, undermines self-consciousness, quashes personalities, instills inferiority complexes, and dives home a void of ambition and initiative.

The Fear of Ill-Health

Disease. “Dis-Ease”. It’s the pill Big Pharma wants us to swallow, and those companies know people are motivated to buy their snake oil products because of health-fear motivation. Sickness is a multi-trillion dollar industry.

Many illnesses are not real. They’re figments of people’s imaginations—just like ghosts. But the fear of disease and the many imagined maladies that infect human minds can manifest as realistic, symptomatic presentations in their bodies. People think themselves into illness and when the symptoms illusionary appear, they’re convinced. And the circle continues.

Many illnesses are not real. They’re figments of people’s imaginations—just like ghosts. But the fear of disease and the many imagined maladies that infect human minds can manifest as realistic, symptomatic presentations in their bodies. People think themselves into illness and when the symptoms illusionary appear, they’re convinced. And the circle continues.

I read a quote from entertainer Naomi Judd. She said, “Your body hears everything your mind says.” She’s right. Autosuggestion works both ways, and you can talk yourself out of ill health fear or what’s called hypochondria.

I respect people who meditate and do yoga. I also respect people who eat right, exercise, and get proper sleep. And I respect people who put their mind into a positive state where they don’t fear poverty or care about what “they” say.

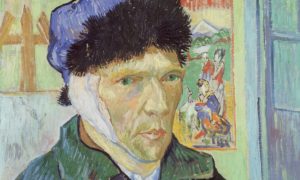

The Fear of Loss of Love

This is the painful ghost. This specter is so excruciatingly cruel. It can cause it’s possessed one to take their own life. This ghost prevails misery and devastation and soulful destruction.

Jealousy doesn’t require a reason. It’s the most unreasonable emotion and sets up irrational fears where it’s a devastating ghost—devastating where there is, or is not, any basis. Real or unreal, the fear of loss of love is awful.

Jealousy doesn’t require a reason. It’s the most unreasonable emotion and sets up irrational fears where it’s a devastating ghost—devastating where there is, or is not, any basis. Real or unreal, the fear of loss of love is awful.

I experienced the loss of love a long time ago. I now call her “She Whose Name Shall Not Be Mentioned”. Losing her was the best thing that ever happened in my life because I wouldn’t have met Rita if I hadn’t lost her. Finding Rita was even better than discovering Napoleon Hill and smashing the six ghosts of fear.

They say if you have to convince someone to stay with you, then they’ve already left. In this case, I have to agree with they. Security in a relationship is a treasure without an appraised value, and I treasure my relationship with Rita above my own life. I don’t fear it. I love it.

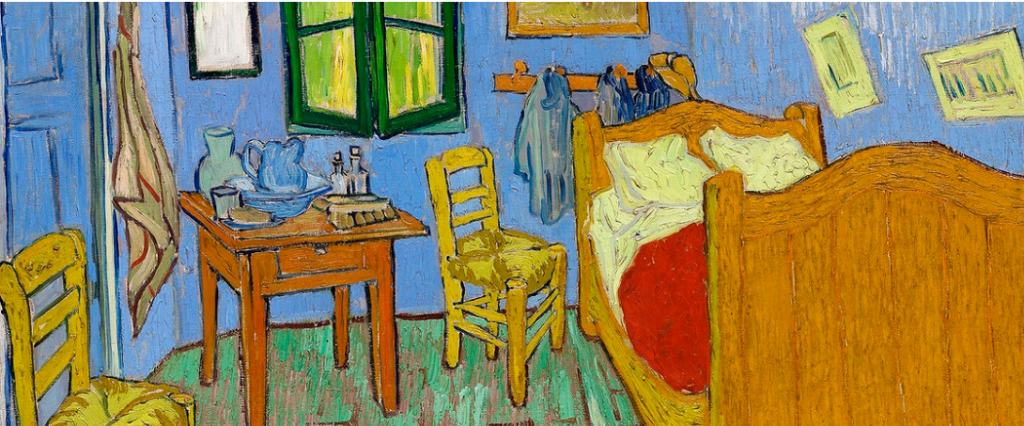

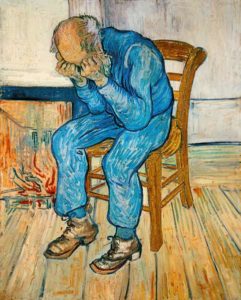

The Fear of Old Age

Your fear of being alone in old age, or being debilitated through wear-out, is understandable. It’s especially understandable if you’ve lived a life filled with the fear of poverty, the fear of criticism, the fear of ill health, and the fear of the loss of love. The combination of these four ghosts—these non-real ghosts—are life-threatening.

Napoleon Hill said, “I don’t know why men and women should be so afraid that they’re gonna dry up and blow away when they get to that ripe old age of forty to fifty. The real achievements of the world were the results of men and women who had gone beyond sixty. The greatest achievement age is between sixty-five and seventy, so I don’t know why anyone should be afraid of old age. Yet they are.”

Napoleon Hill said, “I don’t know why men and women should be so afraid that they’re gonna dry up and blow away when they get to that ripe old age of forty to fifty. The real achievements of the world were the results of men and women who had gone beyond sixty. The greatest achievement age is between sixty-five and seventy, so I don’t know why anyone should be afraid of old age. Yet they are.”

Fearing old age is a ghost. There is no reasonable reason to buy into this BS. Sure, as we age we slow down physically but we’re completely capable of being mentally active as long as we don’t allow the fear ghosts of poverty, criticism, ill-health, and love loss to cripple our mindset.

I turned sixty-five this year. I drank the Napoleon Hill Kool-Aid in my thirties, and it was the best thirst quencher ever. I’m just getting started in life, although it took me this long to get my act together.

The Fear of Death

“It’s the rarest thing in the world to find a person who hasn’t, at one time or another, been afraid of death.” ~Napoleon Hill

“Matter and energy cannot be created or destroyed. They can only be changed from one form of reality to another.” ~Albert Einstein

In my experience in the death business, I’ve been asked a lot of questions, done a lot of research, and soul searched. I believe there is a soul beyond physical matter and energetic action, and I believe it’s a non-physical combination of Infinite Intelligence, or The Creator, employing two functions called consciousness and entropy. But, that’s for another post.

I don’t fear becoming a ghost after death. I look at it like this. I was somewhere before I was born into consciousness as a lump of matter, and I’m living an energetic life constantly being broken down by entropy. When this consciousness I now have finally extinguishes—because entropy’s universal change ultimately conquers a rigid combination of matter and energy—I’ll go back to where I was before I was born, and I’m not afraid.

There are no specters. No illusions. There is only you.

Only in your mind live The Six Ghosts Of Fear.

Conquer them.